Prediabetes is a significant metabolic status since there is high potential for future progression of diabetes mellitus (DM). People with prediabetes are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality. Endothelial and microvascular dysfunction is considered a key step towards the development and progression of CVD. The term microcirculation refers to the circulation in vessels with diameter <150 μm, including the small arteries and veins, as well as the capillaries. The main function of microcirculation is to ensure the provision of nutrients and oxygen to tissues. It also regulates hydrostatic pressure at the level of capillaries and blood flow, and consequently, it helps in the regulation of blood pressure through the increase of peripheral resistance.

- prediabetes

- skin

- retinopathy

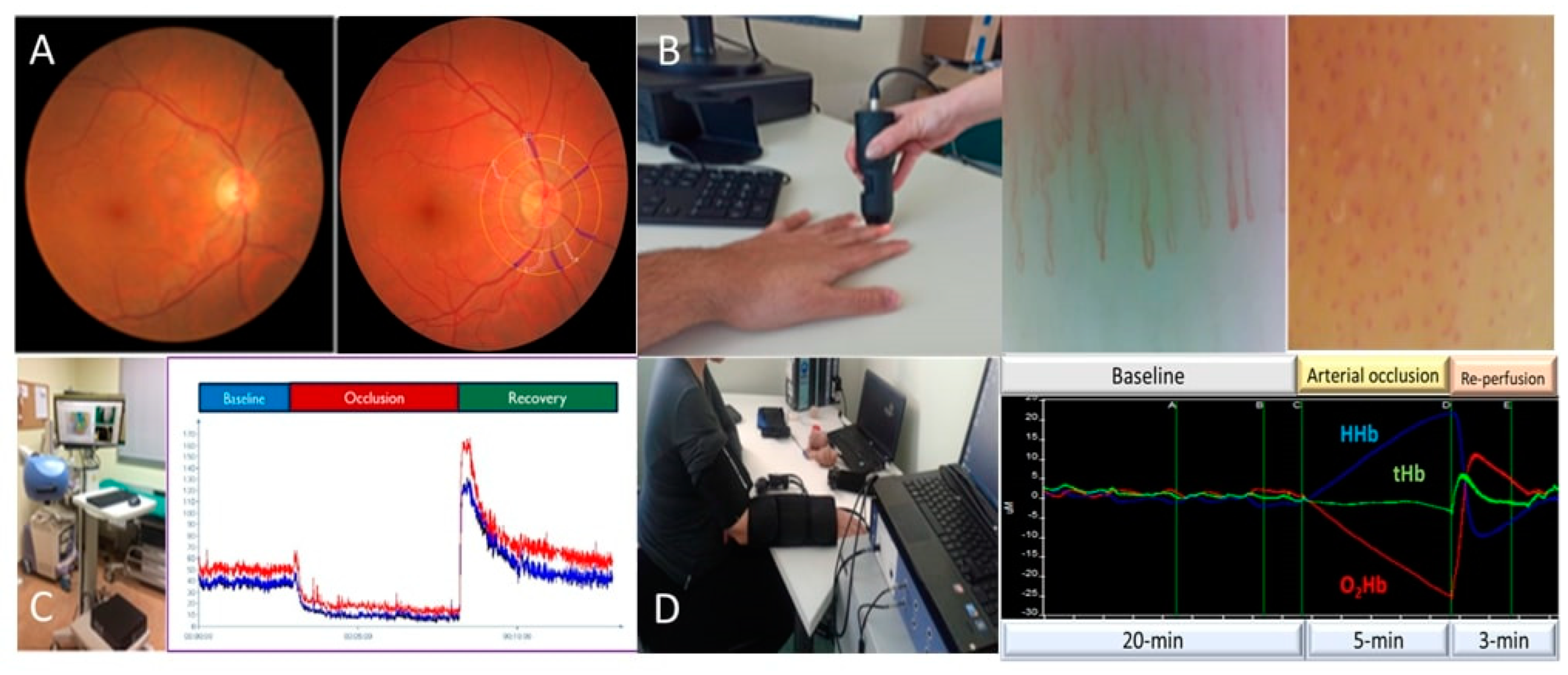

1. Prediabetes and the Retina

2. Prediabetes and Albuminuria

3. Prediabetes and Skin—Muscle Microcirculation

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/life13030644

References

- Cheung, N.; Mitchell, P.; Wong, T.Y. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet 2010, 376, 124–136.

- Yau, J.W.Y.; Rogers, S.L.; Kawasaki, R.; Lamoureux, E.L.; Kowalski, J.W.; Bek, T.; Chen, S.J.; Dekker, J.M.; Fletcher, A.; Grauslund, J.; et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 556–564.

- Klein, R.; Knudtson, M.D.; Lee, K.E.; Gangnon, R.; Klein, B.E.K. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy XXII. The Twenty-Five-Year Progression of Retinopathy in Persons with Type 1 Diabetes. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1859–1868.

- Cheug, N.; Wang, J.J.; Klein, R.; Couper, D.; Sharrett, A.R.; Wong, T.Y. Diabetic Retinopathy and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1742–1746.

- Cheung, N.; Rogers, S.; Couper, D.J.; Klein, R.; Sharrett, A.R.; Wong, T.Y. Is diabetic retinopathy an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke? Stroke 2007, 38, 398–401.

- Lamparter, J.; Raum, P.; Pfeiffer, N.; Peto, T.; Höhn, R.; Elflein, H.; Wild, P.; Schulz, A.; Schneider, A.; Mirshahi, A. Prevalence and associations of diabetic retinopathy in a large cohort of prediabetic subjects: The Gutenberg Health Study. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2014, 28, 482–487.

- Frank, R.N. Diabetic Retinopathy. N. Eng. J. Med. 2004, 350, 48–58.

- Sairenchi, T.; Iso, H.; Yamagishi, K.; Irie, F.; Okubo, Y.; Gunji, J.; Muto, T.; Ota, H. Mild retinopathy is a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in Japanese with and without hypertension the Ibaraki Prefectural Health Study. Circulation 2011, 124, 2502–2511.

- Triantafyllou, A.; Doumas, M.; Anyfanti, P.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Zabulis, X.; Petidis, K.; Gavriilaki, E.; Karamaounas, P.; Gkolias, V.; Pyrpasopoulou, A.; et al. Divergent retinal vascular abnormalities in normotensive persons and patients with never-treated, masked, white coat hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2013, 26, 318–325.

- Anyfanti, P.; Triantafyllou, A.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Koletsos, N.; Athanasopoulos, G.; Zabulis, X.; Galanopoulou, V.; Aslanidis, S.; Douma, S. Retinal vessel morphology in rheumatoid arthritis: Association with systemic inflammation, subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk. Microcirculation 2017, 24, e12417.

- Nathan, D.M.; Chew, E.; Christophi, C.A.; Davis, M.D.; Fowler, S.; Goldstein, B.J.; Hamman, R.F.; Hubbard, L.D.; Knowler, W.C.; Molitch, M.E. The prevalence of retinopathy in impaired glucose tolerance and recent-onset diabetes in the diabetes prevention program. Diabet. Med. 2007, 24, 137–144.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Wang, J.J.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal Vascular Changes in Pre-Diabetes and Prehypertension. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2708–2715.

- Sabanayagam, C.; Lye, W.K.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.K.; Cotch, M.F.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P.; Shaw, J.E.; Selvin, E.; Sharrett, A.R.; et al. Retinal microvascular calibre and risk of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and participant-level meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2476–2485.

- Huru, J.M.; Leiviskä, I.; Saarela, V.; Johanna Liinamaa, M. Prediabetes influences the structure of the macula: Thinning of the macula in the Northern Finland Birth Cohort. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1731–1737.

- Ikram, M.K.; Janssen, J.A.M.J.L.; Roos, A.M.E.; Rietveld, I.; Witteman, J.C.M.; Breteler, M.M.B.; Hofman, A.; Van Duijn, C.M.; De Jong, P.T.V.M. Retinal vessel diameters and risk of impaired fasting glucose or diabetes: The Rotterdam Study. Diabetes 2006, 55, 506–510.

- Kifley, A.; Wang, J.J.; Cugati, S.; Wong, T.; Mitchell, P. Retinal vascular caliber and the long-term risk of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose: The blue mountains eye study. Microcirculation 2008, 15, 373–377.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Wang, J.J.; Islam, F.M.A.; Mitchell, P.; Tapp, R.J.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Simpson, R.; Shaw, J.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal arteriolar narrowing predicts incidence of diabetes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 536–539.

- Tien, Y.W.; Shankar, A.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.K.; Hubbard, L.D. Retinal arteriolar narrowing, hypertension, and subsequent risk of diabetes mellitus. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1060–1065.

- Wong, T.Y.; Klein, R.; Richey Sharrett, A.; Schmidt, M.I.; Pankow, J.S.; Couper, D.J.; Klein, B.E.K.; Hubbard, L.D.; Duncan, B.B. Retinal arteriolar narrowing and risk of diabetes mellitus in middle-aged persons. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002, 287, 2528–2533.

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chu, Z.; Rk, W.; Lu, L.; Zou, H. Early Retinal Microvasculopathy in Prediabetic Patients and Correlated Factors. Ophthalmic Res. 2022, 66, 367–376.

- Ratra, D.; Angayarkanni, N.; Dalan, D.; Prakash, N.; Kaviarasan, K.; Thanikachalam, S.; Das, U. Quantitative analysis of retinal microvascular changes in prediabetic and diabetic patients. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 3226–3234.

- Ratra, D.; Nagarajan, R.; Dalan, D.; Prakash, N.; Kuppan, K.; Thanikachalam, S.; Das, U.; Narayansamy, A. Early structural and functional neurovascular changes in the retina in the prediabetic stage. Eye 2021, 35, 858–867.

- Arias, J.D.; Arango, F.J.; Parra, M.M.; Sánchez-Ávila, R.M.; Parra-Serrano, G.A.; Hoyos, A.T.; Granados, S.J.; Viteri, E.J.; Gaibor-Santos, I.; Perez, Y. Early microvascular changes in patients with prediabetes evaluated by optical coherence tomography angiography. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2021, 13, 1–10.

- Peng, R.P.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Shen, H.Y.; Lin, H.M.; Zhong, L.; Song, S.Q.; Liu, T.; Ling, S.Q. Retinal Nerve and Vascular Changes in Prediabetes. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 777646.

- Lott, M.E.J.; Slocomb, J.E.; Shivkumar, V.; Smith, B.; Quillen, D.; Gabbay, R.A.; Gardner, T.W.; Bettermann, K. Impaired retinal vasodilator responses in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Act. Ophthalmol. 2013, 91, 462–469.

- Care, D. Microvascular complications and foot care: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, S151–S167.

- American Diabetes Association. 9. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care. Diabetes Care 2014, 38, S58–S66.

- Halimi, J.M.; Hadjadj, S.; Aboyans, V.; Allaert, F.A.; Artigou, J.Y.; Beaufils, M.; Berrut, G.; Fauvel, J.P.; Gin, H.; Nitenberg, A.; et al. Microalbuminuria and urinary albumin excretion: French clinical practice guidelines. Diabetes Metab. 2007, 33, 303–309.

- Gerstein, H.C.; Mann, J.F.E.; Yi, Q.; Zinman, B.; Dinneen, S.F.; Hoogwerf, B.; Hallé, J.P.; Young, J.; Rashkow, A.; Joyce, C.; et al. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2001, 286, 421–426.

- Tapp, R.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Balkau, B.; Chadban, S.J.; Tonkin, A.M.; Welborn, T.A.; Atkins, R.C. Albuminuria is evident in the early stages of diabetes onset: Results from the Australian Diabetes, Obesity, and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004, 44, 792–798.

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Narayan, K.M.; Weisman, D.; Golden, S.H.; Jaar, B.G. Association between prediabetes and risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2016, 33, 1615–1624.

- Jung, D.H.; Byun, Y.S.; Kwon, Y.J.; Kim, G.S. Microalbuminuria as a simple predictor of incident diabetes over 8 years in the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15445.

- Xie, Q.; Xu, C.; Wan, Q. Association between microalbuminuria and outcome of non-diabetic population aged 40 years and over: The reaction study. Prim. Care Diabetes 2020, 14, 376–380.

- Bahar, A.; Makhlough, A.; Yousefi, A.; Kashi, Z.; Abediankenari, S. Correlation between prediabetes conditions and microalbuminuria. Nephrourol. Mon. 2013, 5, 741–744.

- Friedman, A.; Marrero, D.; Ma, Y.; Ackermann, R.; Narayan, K.M.V.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Watson, K.; Knowler, W.C.; Horton, E.S. Value of urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio as a predictor of type 2 diabetes in pre-diabetic individuals. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2344–2348.

- Schroijen, M.A.; de Mutsert, R.; Dekker, F.W.; de Vries, A.P.J.; de Koning, E.J.P.; Rabelink, T.J.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Dekkers, O.M. The association of glucose metabolism and kidney function in middle-aged adults. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 14, 2383–2390.

- Won, J.C.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.M.; Han, S.Y.; Noh, J.H.; Ko, K.S.; Rhee, B.D.; Kim, D.J. Prevalence of and factors associated with albuminuria in the Korean adult population: The 2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e83273.

- Markus, M.R.P.; Ittermann, T.; Baumeister, S.E.; Huth, C.; Thorand, B.; Herder, C.; Roden, M.; Siewert-Markus, U.; Rathmann, W.; Koenig, W.; et al. Prediabetes is associated with microalbuminuria, reduced kidney function and chronic kidney disease in the general population: The KORA (Cooperative Health Research in the Augsburg Region) F4-Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 234–242.

- Kim, C.H.; Kim, K.J.; Kim, B.Y.; Jung, C.H.; Mok, J.O.; Kang, S.K.; Kim, H.K. Prediabetes is not independently associated with microalbuminuria in Korean general population: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2012 (KNHANES V-2,3). Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, e18–e21.

- Kuryliszyn-Moskal, A.; Ciolkiewicz, M.; Klimiuk, P.A.; Sierakowski, S. Clinical significance of nailfold capillaroscopy in systemic lupus erythematosus: Correlation with endothelial cell activation markers and disease activity. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2009, 38, 38–45.

- Cutolo, M.; Grassi, W.; Matucci Cerinic, M. Raynaud’s phenomenon and the role of capillaroscopy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 3023–3030.

- Anyfanti, P.; Angeloudi, E.; Dara, A.; Arvanitaki, A.; Bekiari, E.; Kitas, G.D.; Dimitroulas, T. Nailfold Videocapillaroscopy for the Evaluation of Peripheral Microangiopathy in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Life 2022, 12, 1167.

- Triantafyllou, A.; Anyfanti, P.; Pyrpasopoulou, A.; Triantafyllou, G.; Aslanidis, S.; Douma, S. Capillary rarefaction as an index for the microvascular assessment of hypertensive patients. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 33.

- Antonios, T.F.T.; Singer, D.R.J.; Markandu, N.D.; Mortimer, P.S.; MacGregor, G.A. Structural skin capillary rarefaction in essential hypertension. Hypertension 1999, 33, 998–1001.

- Anyfanti, P.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Triantafyllou, A.; Zabulis, X.; Dolgyras, P.; Galanopoulou, V.; Aslanidis, S.; Douma, S. Dermal capillary rarefaction as a marker of microvascular damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Association with inflammation and disorders of the macrocirculation. Microcirculation 2018, 25, e12451.

- Uyar, S.; Balkarli, A.; Erol, M.K.; Yeşil, B.; Tokuç, A.; Durmaz, D.; Görar, S.; Çekin, A.H. Assessment of the relationship between diabetic retinopathy and nailfold capillaries in type 2 diabetics with a noninvasive method: Nailfold videocapillaroscopy. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 7592402.

- Lisco, G.; Cicco, G.; Cignarelli, A.; Garruti, G.; Laviola, L.; Giorgino, F. Computerized video-capillaroscopy alteration related to diabetes mellitus and its complications. In Oxygen Transport to Tissue XL; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 1072, pp. 363–368.

- Hsu, P.C.; Liao, P.Y.; Chang, H.H.; Chiang, J.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Lo, L.C. Nailfold capillary abnormalities are associated with type 2 diabetes progression and correlated with peripheral neuropathy. Med. (United States) 2016, 95, e5714.

- Barchetta, I.; Riccieri, V.; Vasile, M.; Stefanantoni, K.; Comberiati, P.; Taverniti, L.; Cavallo, M.G. High prevalence of capillary abnormalities in patients with diabetes and association with retinopathy. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 1039–1044.

- Rajaei, A.; Dehghan, P.; Farahani, Z. Nailfold Capillaroscopy Findings in Diabetic Patients (A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study). Open J. Pathol. 2015, 05, 65–72.

- Kuryliszyn-Moskal, A.; Zarzycki, W.; Dubicki, A.; Moskal, D.; Kosztyła-Hojna, B.; Hryniewicz, A. Clinical usefulness of videocapillaroscopy and selected endothelial cell activation markers in people with Type 1 diabetes mellitus complicated by microangiopathy. Adv. Med. Sci. 2017, 62, 368–373.

- Irving, R.J.; Walker, B.R.; Noon, J.P.; Watt, G.C.M.; Webb, D.J.; Shore, A.C. Microvascular correlates of blood pressure, plasma glucose, and insulin resistance in health. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 53, 271–276.

- Serné, E.H.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Ter Maaten, J.C.; Ter Wee, P.M.; Rauwerda, J.A.; Donker, A.J.M.; Gans, R.O.B. Microvascular function relates to insulin sensitivity and blood pressure in normal subjects. Circulation 1999, 99, 896–902.

- Boas, D.A.; Dunn, A.K. Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010, 15, 011109.

- Koletsos, N.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Lazaridis, A.; Triantafyllou, A.; Anyfanti, P.; Dolgyras, P.; DIpla, K.; Galanopoulou, V.; Aslanidis, S.; Douma, S. Skin microvascular dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with and without cardiovascular risk factors. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 2834–2841.

- Margouta, A.; Anyfanti, P.; Lazaridis, A.; Nikolaidou, B.; Mastrogiannis, K.; Malliora, A.; Patsatsi, A.; Triantafyllou, A.; Douma, S.; Doumas, M.; et al. Blunted Microvascular Reactivity in Psoriasis Patients in the Absence of Cardiovascular Disease, as Assessed by Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging. Life 2022, 12, 1796.

- Anyfanti, P.; Gavriilaki, E.; Dolgyras, P.; Nikolaidou, B.; Dimitriadou, A.; Lazaridis, A.; Mastrogiannis, K.; Koletsos, N.; Triantafyllou, A.; Dimitroulas, T.; et al. Skin microcirculation dynamics are impaired in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no cardiovascular comorbidities. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2023.

- Dolgyras, P.; Lazaridis, A.; Anyfanti, P.; Gavriilaki, E.; Koletsos, N.; Triantafyllou, A.; Nikolaidou, B.; Galanapoulou, V.; Douma, S.; Gkaliagkousi, E. Microcirculation dynamics in systemic vasculitis: Evidence of impaired microvascular response regardless of cardiovascular risk factors. Rheumatology 2022, keac652.

- Lazaridis, A.; Triantafyllou, A.; Dipla, K.; Dolgyras, P.; Koletsos, N.; Anyfanti, P.; Aslanidis, S.; Douma, S.; Gkaliagkousi, E. Skin microvascular function, as assessed with laser speckle contrast imaging, is impaired in untreated essential and masked hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2022, 45, 445–454.

- Gkaliagkousi, E.; Lazaridis, A.; Anyfanti, P.; Stavropoulos, K.; Imprialos, K.; Triantafyllou, A.; Mastrogiannis, K.; Douma, S.; Doumas, M. Assessment of skin microcirculation in primary aldosteronism: Impaired microvascular responses compared to essential hypertensives and normotensives. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 36, 1066–1071.

- de Matheus, A.S.; Clemente, E.L.S.; de Lourdes Guimarães Rodrigues, M.; Torres Valença, D.C.; Gomes, M.B.; Alessandra, A.S.; Clemente, E.L.S.; de Lourdes Guimarães Rodrigues, M.; Torres Valença, D.C.; Gomes, M.B. Assessment of microvascular endothelial function in type 1 diabetes using laser speckle contrast imaging. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 753–757.

- Mennes, O.A.; Van Netten, J.J.; Van Baal, J.G.; Steenbergen, W. Assessment of microcirculation in the diabetic foot with laser speckle contrast imaging. Physiol. Meas. 2019, 40, 065002.

- Dipla, K.; Triantafyllou, A.; Grigoriadou, I.; Kintiraki, E.; Triantafyllou, G.A.; Poulios, P.; Vrabas, I.S.; Zafeiridis, A.; Douma, S.; Goulis, D.G. Impairments in microvascular function and skeletal muscle oxygenation in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: Links to cardiovascular disease risk factors. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 192–201.

- Townsend, D.K.; Deysher, D.M.; Wu, E.E.; Barstow, T.J. Reduced insulin sensitivity in young, normoglycaemic subjects alters microvascular tissue oxygenation during postocclusive reactive hyperaemia. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 967–974.

- Soares, R.N.; Reimer, R.A.; Murias, J.M. Changes in vascular responsiveness during a hyperglycemia challenge measured by near-infrared spectroscopy vascular occlusion test. Microvasc. Res. 2017, 111, 67–71.