Bacterial infections are a growing concern to the health care systems. Bacteria in the human body are often found embedded in a dense 3D structure, the biofilm, which makes their eradication even more challenging. Indeed, bacteria in biofilm are protected from external hazards and are more prone to develop antibiotic resistance. Moreover, biofilms are highly heterogeneous, with properties dependent on the bacteria species, the anatomic localization, and the nutrient/flow conditions. Therefore, antibiotic screening and testing would strongly benefit from reliable in vitro models of bacterial biofilms.

1. Introduction

Bacteria are versatile microorganisms that can easily adapt to different environmental conditions through the modulation of their genetic expression, in particular by turning on stress-response genes.

One of the main strategies to survive harsh environments is to shift from an individual and proliferative state (planktonic state) to a more organized and static condition (sessile state). In the sessile state, bacteria are packed in complex communities embedded in an extracellular matrix (ECM) known as biofilm, which is composed of a wide range of macromolecules produced by bacteria called extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). EPS, which are mainly exopolysaccharides, proteins, and DNA, form three-dimensional structures that improve intercellular communications and nutrient exchange, while also providing protective functions.

Bacteria embedded in biofilms are more resistant to chemical challenges, such as exposure to disinfectants and antibiotics. This is particularly relevant in the medical field since more than 80% of the infections that develop in the body are associated with biofilm formation. Biofilm-associated infections can develop spontaneously in different organs and tissues, or they may arise after the implantation of external devices. In the first case, the patient often develops chronic infections, such as cystic fibrosis, osteomyelitis and non-healing wounds. In the second case, the infection begins on and develops from the surface of implants such as heart valves, orthopedic prostheses and catheters.

Because of their chronic nature and heterogeneity, biofilm-associated infections are a serious threat for the patients and a burden for the health care system. Moreover, the spread of antibiotic resistance has reduced the effectiveness of the available treatments, requiring the development of innovative and more effective strategies.

Reliable models that mimic the complexity of the biological environment have the potential to advance our knowledge on the biofilm dynamic and composition and to improve the screening and the design of new treatment options. Unfortunately, the biofilm architecture as well as the specific EPS composition are strongly influenced by the bacterial species involved and by the environmental conditions, making biofilm extremely variable and complex to understand and model. Animal and in vitro models of infections have been widely used. However, traditional 2D in vitro models tend to be simple and unable to reproduce the complexity found in nature, while in vivo models are expensive and raise ethical concerns. In the last decades, increasing attention was put on developing complex in vitro 3D models of biofilms using innovative technologies. For instance, 3D-printing technology allowed a more accurate reproduction of the biofilm architecture, while microfluidic devices have been exploited to mimic specific environmental conditions, such as flow or nutrient gradients. Moreover, these models can include human cells as well as ECM components or can be integrated with other tissue models, with the aim to better mimic the interactions between bacteria and the host. These systems are known as microcosm models.

2. Lifecycle and Structure of Biofilms

Biofilms are complex communities in which bacteria of different species cooperate. Their architecture and their mechanical and chemical properties depend on several factors, mainly related to the types of bacteria present and the environmental conditions under which the biofilm grows. The biofilm lifecycle is complex, and a variety of processes occur and overlap during its development, depending on the bacterial species involved and on the characteristics of the substrate.

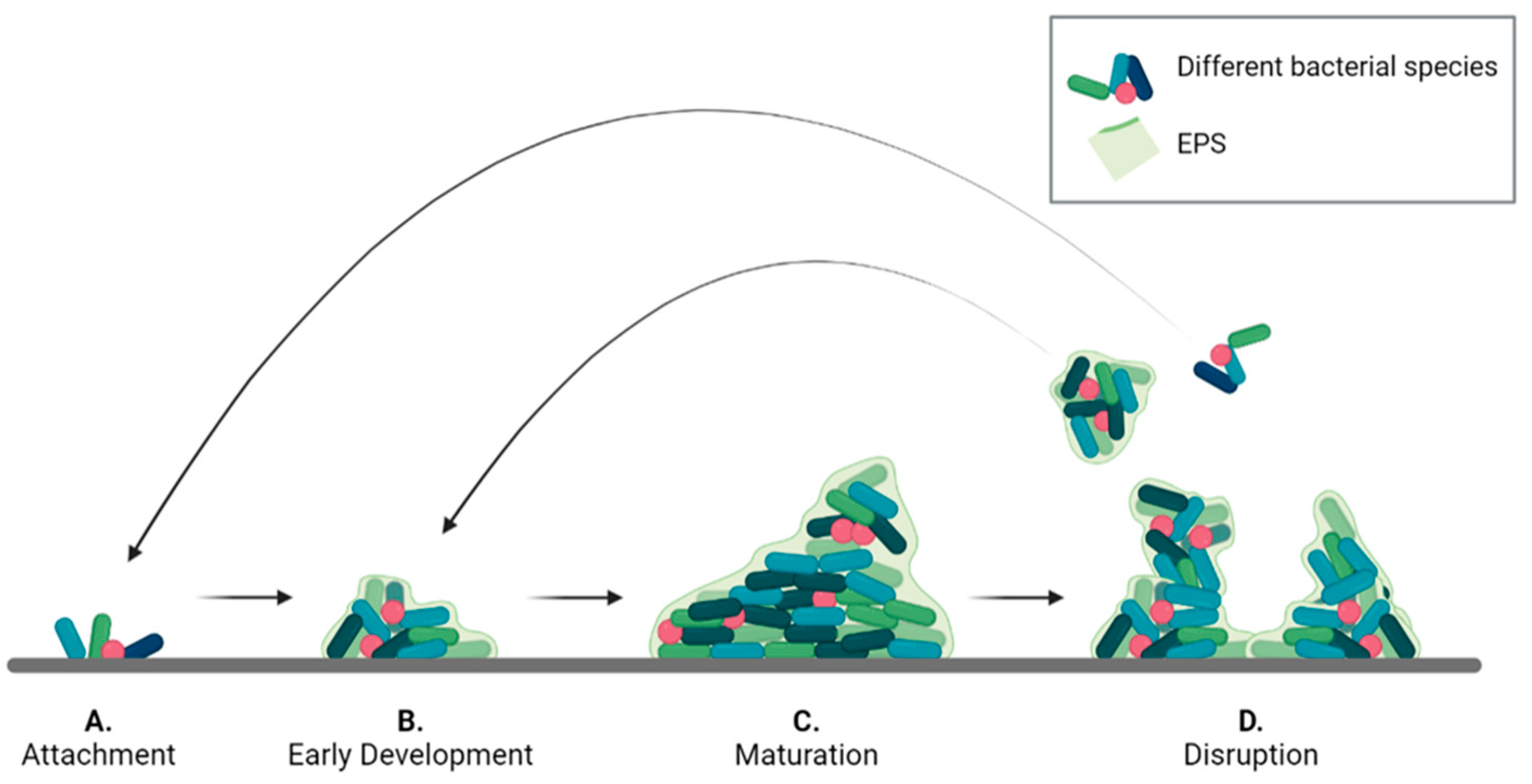

A common development pattern can be identified for all types of biofilms, divided into the four phases described in Figure 1. Initially, single planktonic cells and/or aggregates attach to the surface by transient interactions that later develop into a more robust adhesion. The success of this phase, known as attachment (Figure 1A), depends on different factors including surface chemistry and morphology, temperature, pressure, presence of flow, as well as steric or electrostatic interactions. For instance, S. epidermidis has been shown to colonize titanium implant surfaces to a different extent depending on their roughness. Moreover, some bacteria present filamentous structures, such as pili and flagella, that can interact with surfaces to promote adhesion. Once the bacteria are stably adherent, surface colonization begins by producing EPS. In the early development stage (Figure 1B), bacteria divide and recruit other planktonic cells by aggregation and agglutination. Later, bacteria expand to form microcolonies by chemically communicating with each other and by expressing genes for EPS secretion. In this phase, a 3D architecture is developed to allow network stabilization and to facilitate intercellular signaling.

Figure 1. Bacterial biofilm life cycle divided into the four phases: (A) attachment, (B) early development, (C) maturation, and (D) disruption.

In the maturation phase (Figure 1C) the bacterial aggregates thicken and become macro-colonies. In this process, that may take several days, gradients of nutrients, oxygen and pH within the biofilm, play a pivotal role influencing bacterial metabolism in the different biofilm regions.

After reaching maturity, biofilms undergo a partial disruption (Figure 1D) that is mediated by two different processes: detachment, and dispersion. In the first case, external forces, such as mechanical and shear stress, cause the release of biofilm portions. The released cells are in a sessile state and are partially embedded in the EPS matrix, which protects them from the environment. Dispersion is a response to internal stress, such as high proliferation rate, or to external stimuli, such as variation in nitric oxide or oxygen levels. These stimuli induce cells to switch back en masse to the planktonic state and to escape the biofilm to colonize other areas. The result is the formation of voids or cavities within the biofilm structure. Moreover, the process leaves the released cell more vulnerable to external chemicals, such as antibiotics and disinfectants.

Biofilm architecture and composition are highly heterogeneous with clusters of cells incorporated in EPS and interstitial voids that facilitate oxygen and nutrient transport. The cells within a biofilm can have different phenotypes because of the gradients of nutrients and oxygen. For instance, bacteria in the inner part of biofilm have lower metabolic activity, since their access to nutrients is limited, and are more resistant to antimicrobial agents. These cells are known as ‘persister cells’, having a dormant phenotype that can switch back to an active state under favorable environmental conditions.

2.1. The EPS Composition

The EPS matrix may account for 50% to 90% of the biofilm composition, depending on the bacterial strains present, the stage of biofilm development and the environmental conditions (e.g., shear forces, temperature, and nutrient availability). These factors also influence the composition of the EPS, giving rise to a multitude of different biofilms.

Exopolysaccharides are the major fraction of the EPS and are essential for biofilm maturation since they are involved in nutrient sequestration and biofilm attachment. Exopolysaccharides are long-chain polymers mainly composed of carbohydrates. Each bacterial species assembles specific exopolysaccharides. For example, alginate, a polyanionic exopolysaccharide composed of uronic acid, is characteristic of P. aeruginosa biofilms. On the contrary, in S. aureus infections, biofilms are composed of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA), which is a polycationic exopolysaccharide.

Proteins are also a major class of EPS components. Among these, many different enzymes are involved in the synthesis and degradation of the EPS and contribute to matrix remodeling in all stages of biofilm formation. Some enzymes can produce long-chain biopolymers that are stored as nutrient source.

Enzymes are also important for biofilm detachment and dispersion when the EPS is partially degraded to release bacteria. Examples of enzymes with this function are dispersin B, which degrades N-acetylglucosamine-containing extracellular polysaccharides, and the surface protein-releasing enzyme (SPRE), that releases adhesin P1 from the bacteria surface allowing for Streptococcus mutans detachment from surfaces.

Non-enzymatic proteins play mainly a structural role by connecting the exopolysaccharide matrix with the bacteria outer membrane. For instance, lectins, a category of extracellular carbohydrate-binding proteins are implicated in cell-to-cell interactions within the biofilms, thus supporting microcolonies formation and biofilm maturation. Biofilm-associated surface proteins, a class of high molecular mass proteins located on the bacterial surface, are known to promote biofilm formation in several bacterial species, such as S. aureus, by facilitating primary attachment to abiotic surfaces and intercellular adhesion.

Extracellular DNA (eDNA) is another important component of the EPS acting as intercellular connector and signaling molecule. Its occurrence varies largely depending on the type of microorganisms present. For example, it is a major component of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus biofilms, while it is only minimally present in S. epidermidis biofilms.

2.2. Mechanical Properties of Biofilms

Since the biofilm composition varies greatly depending on the microorganism species and the environmental conditions, there is also a huge variability in its mechanical properties. Moreover, biofilms are living structures, thus their properties, including the mechanical characteristics, change over time.

Macro-mechanical tests, such as rotational shear rheology, have given some preliminary information about the biofilm as a bulk, showing that it behaves as a viscoelastic material because of its heterogeneous composition, which include water, bacterial cells, and EPS.

Viscoelastic materials present a complex shear modulus (G*) which accounts for an elastic component (represented by the storage modulus G’), and a viscous component (represented by the loss modulus G’’). When G’ > G’’ the material behaves as a viscous solid, while if G’ < G’’ the material is defined as a viscoelastic liquid. Biofilms behave as viscous solids until a yield point, where they switch to a viscoelastic liquid behavior.

Environmental factors, such as shear flow, temperature, pH, and ion concentration greatly influence the biofilm mechanical properties. For instance, increasing values of the elastic modulus (from 0.9 to 100 Pa) have been reported when shear flow increases from 0.05 to 5 N/m2. E. coli has been shown to produce a higher concentration of curli fibers at 30 °C, resulting in a stiff biofilm with average compliance of 0.08.

EPS secretion is also pH-dependent. Group B Streptococcus, a bacterium involved in vaginal infections, has been shown to preferentially form biofilms at low pH. Indeed, Ho et al. evaluated the elastic moduli of biofilms grown on glass slides under different pH conditions and found Young’s Modulus values ranging from 2 to 100 kPa as the pH increased. This increase in the elastic modulus was attributed to the inability of bacteria to produce a biofilm at pH 7, since the measured value was close to that of the glass slide.

Another aspect to consider is the biofilm internal heterogeneity, which results in variable mechanical properties within the matrix. Thus, evaluation of the mechanical properties at the microscale level should be performed to identify variations within the biofilm bulk.

2.3. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Biofilms

It is known that bacterial biofilms can tolerate concentrations of antibiotics 10 to 1000 times higher than those that are harmful for their planktonic counterparts, thus increasing the possibility of chronicity of medical device-associated infections.

The mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in bacterial sessile communities have been described by Stewart and Costerton in a landmark review. According to these authors, the common molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance do not seem to be responsible for the preservation of bacteria in a biofilm, as demonstrated by the fact that even susceptible bacteria that do not possess genes for antibiotic resistance can become highly resistant to antibiotics when they live in a sessile form. It is supposed that the remarkable resilience of bacteria in biofilms derives from the exceptional heterogeneity of cells that reside in the biofilm. Microbes that reside in the inner parts of the biofilm have more difficulty in obtaining nutrients and oxygen and therefore grow slower than those living on the surface. This is a defense mechanism as many antibiotics are only active against fast growing cells, and therefore slow growing cells within the biofilm tend to be spared.

Quorum sensing (QS) is a complex system of microbial communication based on signal molecules that allows bacteria to perceive when a critical concentration of bacteria is reached and activate genes such as those for the production of virulence factors and the development of the biofilm itself.

In addition, a fascinating explanation for biofilm tolerance to antibiotics is the presence, within the biofilm, of peculiar cell types called “persisters”, i.e., slow-growing variants genetically programmed to endure environmental stress, including exposure to antibiotics.

3. Biofilm Models

The last decades have seen a growing interest in the development of models to deepen the knowledge on biofilm formation and to assess the effectiveness of antibacterial treatments. These models can be divided into

in vitro and

in vivo systems.

In vivo models are a fundamental step to link the results of

in vitro studies with clinical trials since they give more accurate information about the safety and the efficacy of new treatments. In particular, they allow to observe the response of the host immune system to the biofilm infection. However,

in vivo models are expensive and can give rise to ethical concerns. On the other hand,

in vitro models are cheap, but allow only for preliminary assessment of treatment efficacy. They often use a single bacterial species, which is hardly ever the case in a natural environment. Moreover, they do not reproduce accurately the nutritional conditions and the substrate on which the biofilm is developed. Progress has been achieved by developing 3D and microcosm models that can better replicate the biofilm architecture and the host environment.

3.1. 3D Models of Bacterial Biofilm

Two main approaches can be employed to obtain 3D models of biofilm

in vitro: the static or the dynamic approach. In the first case, the system is closed, and the biofilm develops on multi-well plates. The advantages of these systems are that they are cheap, do not require any specialized equipment, and allow for high throughput screening of multiple organisms and treatments. However, there is no continuous nutrient replacement and waste removal, which has a deleterious effect on bacteria viability and does not recapitulate well the

in vivo flow and nutrient conditions. On the contrary, dynamic systems are open and allow the exchange of nutrients and waste, resulting also in longer lasting models. Moreover, specific environmental parameters, such as shear stress, can be considered, allowing a more reliable analysis of biofilm development and its resistance to treatments. However, they are more complex and may require specific equipment and technical competences to be implemented.

3.2. Static In Vitro Models of Biofilm

Among the static models, the microtiter plate (MTP), the Calgary biofilm device (CBD), and the Biofilm Ring Test (BRT) are the most common.

In the MTP, bacteria are grown in polystyrene wells, where they are allowed to form the biofilm. The resulting biofilm remains attached to the well bottom and can be analyzed for changes in biomass through colorimetric assays, such as crystal violet. However, the method does not allow a precise quantification, since it measures also the biomass produced by sedimented cells, which are not involved in the biofilm formation.

CBD overcomes this issue by allowing the biofilm to grow on an insert attached to the coverslip. Thus, only the biomass derived from sessile development is quantified.

BRT is based on the capacity of bacteria to entrap magnetic beads during early phases of biofilm formation. When a magnetic field is applied, free magnetic beads move toward the magnetic field and the level of biofilm maturity can be assessed by the quantity of entrapped beads. This can be performed at different timepoints to study also the early phases of biofilm development. The main common limitation of the above methods is that the biofilm usually develops on a 2D substrate which does not recapitulate the 3D complexity of the in vivo environment, resulting in biofilms that do not replicate bacteria resistance.

3.3. Dynamic In Vitro Models of Biofilm

Dynamic systems allow a continuous flow of nutrients and waste products. Thus, biofilm development can be studied over several weeks. The most employed dynamic models, are the modified Robbins device (MRD), the Drip flow reactor (DFR), rotary reactors, and microfluidic systems. In the MRD and DFR, the biofilm grows under selected hydrodynamic conditions (e.g., flow rate, shear stress) on coupons or microscopy slides that can be removed for analysis. The MRD systems are composed of a pipe with holes in which the coupons are placed. The flow speed inside the pipe can be controlled so that biofilm development can be studied under different flow conditions. For instance, Raad et al. studied the effect of different antimicrobials in a model of infected catheter developed within a MRD system. To produce the model, silicone catheter segments were placed on the specimen plugs of the MRD system and maintained in contact with the solution containing two different microbial species involved in catheters infections (i.e., methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and Candida parapsilosis). The obtained infected catheters were then incubated with different antimicrobials to assess their effectiveness.

DRF systems consist of a tilted chamber in which a slide is inserted. During operation, a small amount of fluid passes through the chamber, producing slow shear conditions. This system is suitable for studying the heterogeneity and presence of gradients within the biofilm.

Rotatory reactors are composed of rotating cylinders or disks that provide surface shear. The coupons can be placed either on the rotating or on the fixed structure and are subjected to shear stress depending on their angular positioning. The advantage of these systems is that shear stress is given by the disk rotation and not by the flow rate, therefore these two parameters can be controlled independently. An example of rotary reactors is the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) biofilm reactor in which several rods containing coupons are placed in a vessel and the shear stress is provided by magnetic stirring in the center. In this way, biofilms can be grown under shear stress, as compared to MRD systems. The CDC biofilm reactor is routinary used in the standard methods (E2196-12 and E2562-12) of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) to assess biofilm formation and prevention on surfaces and devices.

3.4. Microcosm Models

Microcosm models can be static or dynamic systems which include additional features, such as cells, materials, or nutrients to better mimic the pathological environment.

To reproduce the pathological/physiological environment in which the biofilm develops, microcosm models can include artificial or ex vivo-derived substrates, cells, and media to simulate a disease-specific ECM. They can also include more than a single bacterial species to model biofilm complexity. Moreover, they should be designed for long term study by including systems for continuous media recycling to extend the lifespan of the model.

For instance, Raic et al. developed an osteomyelitis model by culturing P. aeruginosa or S. aureus on a 3D bone marrow analogue composed of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (hHSPCs) seeded on an artificial scaffold. With this model they could follow proliferation and differentiation of hHSPCs over 7 days and study the effects of infection on hematopoiesis.

Ex vivo-derived tissues can also be used to develop microcosm models. Sánchez et al. studied the formation of multi-species biofilm on implant surfaces, by using saliva collected from donors to coat the implants prior to bacteria seeding to better simulate the oral environment. They were able to follow and characterize the development of the biofilm until maturation in terms of structure and bacterial composition, demonstrating consistency with in vivo observations.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nano13050904