The COVID-19 pandemic has affected more than 214 countries across the world, disrupting the supply of essential commodities. As the pandemic has spread, humanitarian activities (HAs) have attempted to manage the various situation but appear ineffective due to lack of collaboration and information sharing, inability to respond towards disruption, etc. Developing a sustainable humanitarian supply chain (HSC) for managing disasters/emergencies can be viewed as an extension of the traditional supply chain. Thus, sustainable HSCs have evolved as a specialized discipline with a focus on social sustainability.

- humanitarian activities (HAs)

- humanitarian organization (HO)

- pandemic disruption

- COVID-19

1. Introduction

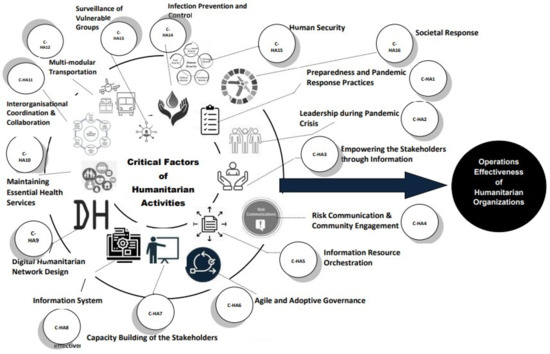

2. Humanitarian Activities (HAs) in Enhancing Operational Effectiveness during the Pandemic

| Critical Factors | Operational Effectiveness during the Pandemic | References |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-modal transportation (C-HA1) |

Usage of multi-modal transportation can connect all supply nodes, affected areas, and logistics operational areas. | [54] |

| Leadership during pandemic crisis (C-HA2) | Communicating with teams, stakeholders, and communities during COVID-19 enhances transparency, demonstrates vulnerability, and builds resilience among humanitarian organizations. | [56] |

| Empowering the stakeholders (C-HA3) | Empowerment of the stakeholders helps the humanitarian organizations to identify clear vision, competency, and coordination across all levels. | [29][38] |

| Risk communication and community engagement (C-HA4) |

Risk communication across stakeholders brings transparency and pro-activeness towards the pandemic situation. | [56] |

| Information resource orchestration (C-HA5) |

Adoption of information resource activities and information behavior activities can meet the need of humanitarian operations. | [49][64] |

| Agile and adaptive governance (C-HA6) | Participation collaboration and governance become more agile and adaptive during the pandemic. | [60][61] |

| Information system (C-HA7) | Information system planning should address challenges, value generation processes, and resource base in an effort to improve organizational performance | [63][65][86][87] |

| Capacity building of stakeholders (C-HA8) | A competency-based teaching approach can improve the intercultural pandemic training among the stakeholders who can further improve interdisciplinary integration, enhancing the overall operational effectiveness. | [57] |

| Blockchain-enabled digital humanitarian network (BT-DHN) (C-HA9) | Blockchain-enabled digital humanitarian network (BT-DHN) ensures participative management and real-time information flow that uses big data for the humanitarian response for effective relief operations. | [2][4] |

| Maintaining essential health services (C-HA10) | Adjust governance and coordination mechanisms to support timely action for essential health services and adapt to changing contexts and needs. | [20][26][52] |

| Inter-organizational coordination and collaboration (C-HA11) |

Collaborative planning for responding the pandemic (through cooperation, interaction, and collaboration among relief agencies). | [29][38] |

| Preparedness and pandemic response practices (C-HA12) | Preparedness planning and COVID-19 response practices emerged as the key humanitarian activity among humanitarian actors. | [42][46] |

| Surveillance for vulnerable groups (C-HA13) | It aims to limit the spread of the pandemic in vulnerable groups (children, women, and the old-age population) by rapid detection, isolation, testing, and management. | [88][89] |

| Prevention and control (C-HA14) |

Infection prevention and control (IPC) is the key humanitarian activity. IPC occupies a unique position in the field of patient safety and quality universal health coverage. | [3] |

| Human security (C-HA15) | It is protecting human life, especially the vulnerable groups, by involving local government and partners to increase operational effectiveness. | [39] |

| Societal response (C-HA16) | It is the collective efforts of humanitarian organizations, the corporate world, government, and the community to fight collectively against the pandemic. Based on the principle of ‘Respond, Recover and Rebuild’, the societal response to the COVID-19 pandemic is a continuous improvement process. | [39][40] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su14031904

References

- Sharma, M.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A. Developiforng a framework for enhancing survivability of sustainable supply chains during and post-COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2020, 1–21.

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Bryde, D.J.; Dwivedi, Y.; Papadopoulos, T. Blockchain technology for enhancing swift-trust, collaboration and resilience within a humanitarian supply chain setting. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3381–3398.

- Wagner, S.M.; Thakur-Weigold, B.; Gatti, F.; Stumpf, J. Measuring and improving the impact of humanitarian logistics consulting. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 83–103.

- Queiroz, M.M.; Fosso Wamba, S.; De Bourmont, M.; Telles, R. Blockchain adoption in operations and supply chain man-agement: Empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 6087–6103.

- Dash, M.; Shadangi, P.Y.; Muduli, K.; Luhach, A.K.; Mohamed, A. Predicting the motivators of telemedicine acceptance in COVID-19 pandemic using multiple regression and ANN approach. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021, 24, 319–339.

- Sahoo, K.K.; Muduli, K.K.; Luhach, A.K.; Poonia, R.C. Pandemic COVID-19: An empirical analysis of impact on Indian higher education system. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021, 24, 341–355.

- Baveja, A.; Kapoor, A.; Melamed, B. Stopping Covid-19: A pandemic-management service value chain approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 289, 173–184.

- Bag, S.; Yadav, G.; Wood, L.C.; Dhamija, P.; Joshi, S. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: Resource melioration in logistics. Resour. Policy 2020, 68, 101776.

- Schiffling, S.; Hannibal, C.; Fan, Y.; Tickle, M. Coopetition in temporary contexts: Examining swift trust and swift distrust in humanitarian operations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 1449–1473.

- Chou, K.P.; Prasad, M.; Lin, Y.Y.; Joshi, S.; Lin, C.-T.; Chang, J.Y. Takagi-Sugeno-Kang type collaborative fuzzy rule based system. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Data Mining (CIDM), Orlando, FL, USA, 9–12 December 2014; pp. 315–320.

- Zwitter, A.; Boisse-Despiaux, M. Blockchain for humanitarian action and development aid. J. Int. Humanit. Action 2018, 3, 16.

- Banomyong, R.; Varadejsatitwong, P.; Oloruntoba, R. A systematic review of humanitarian operations, humanitarian logistics and humanitarian supply chain performance literature 2005 to 2016. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 71–86.

- Gupta, P.K.; Kumar, A.; Joshi, S. A review of knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 with future directions and open challenges. J. Public Aff. 2020, 21, e2555.

- Joshi, S. E-Supply Chain Collaboration and Integration: Implementation Issues and Challenges. In E-Logistics and E-Supply Chain Management: Applications for Evolving Business; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2013.

- Joshi, R.; Joshi, S. Assessing the Readiness of Farmers towards Cold Chain Management: Evidences from India. In Designing and Implementing Global Supply Chain Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 219–235.

- Joshi, S. Designing and Implementing Global Supply Chain Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015.

- Joshi, S.; Singh, R.K.; Sharma, M. Sustainable Agri-food Supply Chain Practices: Few Empirical Evidences from a Developing Economy. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 0972150920907014.

- Kovács, G.; SigalaI, F. Lessons learned from humanitarian logistics to manage supply chain disruptions. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 57, 41–49.

- Kusumastuti, R.D.; Arviansyah, A.; Nurmala, A.; Wibowo, S.S. Knowledge management and natural disaster preparedness: A systematic literature review and a case study of East Lombok, Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 58, 102223.

- Ab Malik, M.H.; Omar, E.N.; Maon, S.N. Humanitarian Logistics: A Disaster Relief Operations Framework During Pandemic Covid-19 in Achieving Healthy Communities. Adv. Bus. Res. Int. J. 2020, 6, 101–113.

- Joshi, S. Social network analysis in smart tourism-driven service distribution channels: Evidence from tourism supply chain of Uttarakhand, India. Int. J. Digit. Cult. Electron. Tour. 2018, 2, 255–272.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Kler, R. Modeling Circular Economy Dimensions in Agri-Tourism Clusters: Sustainable Performance and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2020, 5, 1046–1061.

- Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, J.; Yang, H.; Shang, H. Reinforcement learning approach for resource allocation in humanitarian logistics. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 173, 114663.

- Kunz, N.; Gold, S. Sustainable humanitarian supply chain management—Exploring new theory. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2017, 20, 85–104.

- Kelman, I. COVID-19: What is the disaster? Soc. Anthropol. 2020, 28, 296–297.

- Seddighi, H. COVID-19 as a Natural Disaster: Focusing on Exposure and Vulnerability for Response. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2020, 14, e42–e43.

- Li, J.; An, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Combating the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of disaster experience. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2021, 60, 101581.

- Schiffling, S.; Hannibal, C.; Tickle, M.; Fan, Y. The implications of complexity for humanitarian logistics: A complex adaptive systems perspective. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 1–32.

- Muggy, L.; Stamm, J.L.H. Decentralized beneficiary behavior in humanitarian supply chains: Models, performance bounds, and coordination mechanisms. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 284, 333–365.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Singh, R.K. Performance Evaluation of Agro-tourism Clusters using AHP–TOPSIS. J. Oper. Strat. Plan. 2020, 3, 7–30.

- Charles, A.; Lauras, M.; Van Wassenhove, L.N.; Dupont, L. Designing an efficient humanitarian supply network. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 47-48, 58–70.

- Queiroz, M.M.; Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A.; Wamba, S.F. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 238, 329–354.

- Thompson, D.D.; Anderson, R. The COVID-19 response: Considerations for future humanitarian supply chain and logistics management research. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 11, 157–175.

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Parekh, H.; Joshi, S. Modeling the internet of things adoption barriers in food retail supply chains. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 154–168.

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. Viability of intertwined supply networks: Extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 2904–2915.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M. Impact of sustainable Supply Chain Management on the Performance of SMEs during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Indian Perspective. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10453/152609 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M. Prolonging retailer-supplier relationship: A study of retail firms during pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. Logist. Econ. Glob. 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10453/152610 (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Akhtar, P.; Marr, N.; Garnevska, E. Coordination in humanitarian relief chains: Chain coordinators. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 2, 85–103.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M. Digital technologies (DT) adoption in agri-food supply chains amidst COVID-19: An approach to-wards food security concerns in developing countries. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Source. 2021.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Managing disruptions and risks amidst COVID-19 outbreaks: Role of blockchain technology in developing resilient food supply chains. Oper. Manag. Res. 2021, 1–14.

- Shanker, S.; Barve, A.; Muduli, K.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Joshi, S. Enhancing resiliency of perishable product supply chains in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 1–25.

- Malmir, B.; Zobel, C.W. An applied approach to multi-criteria humanitarian supply chain planning for pandemic response. J. Humanit. Logistics. Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 11, 320–346.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M. Social capital in the Asia Pacific: Examples from the services industry. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2018, 25, 457–458.

- Tripathi, G.; Joshi, S. Creating Competitive Advantage through Sustainable Supply Chains: A Theoretical Framework for the Assessment of Practices, Dynamic Capabilities, and Enterprise Performance of Manufacturing Firms. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 7863–7875.

- Ivanov, D. Lean resilience: AURA (Active Usage of Resilience Assets) framework for post-COVID-19 supply chain management. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021.

- Swain, S.; Peter, O.; Adimuthu, R.; Muduli, K. BlockChain Technology for Limiting the Impact of Pandemic: Challenges and Prospects. In Computational Modelling and Data Analysis in COVID-19 Research; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 165–186.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Bisht, P.; Singh, S. Explaining the Factors Influencing Consumer Perception, Adoption Readiness, and Perceived Usefulness toward Digital Transactions: Online Retailing Experience of Millennials in India. J. Oper. Strat. Plan. 2021, 4, 202–223.

- Blecken, A. Humanitarian Logistics: Modelling Supply Chain Processes of Humanitarian Organizations; Haupt Verlag AG: Bern, Switzerland, 2010; p. 18.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Kumar, S.; Pant, M.K. Co-Creation Among Small Scale Tourism Firm: Role of Information Com-munication and Technology in Productivity and Sustainability. Int. J. Strateg. Inf. Technol. Appl. 2018, 9, 1–14.

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M.; Rathi, S. Forecasting in Service Supply Chain Systems: A State-of-the-Art Review Using Latent Semantic Analysis. Adv. Bus. Manag. Forecast. 2017, 12, 181–212.

- Prasad, M.; Li, D.L.; Lin, C.T.; Prakash, S.; Singh, J.; Joshi, S. Designing Mamdani-Type Fuzzy Reasoning for Visualizing Prediction Problems Based on Collaborative Fuzzy Clustering. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2015, 42.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S. Barriers to blockchain adoption in health-care industry: An Indian perspective. J. Glob. Oper. Strat. Sourc. 2021, 14, 134–169.

- Polater, A. Dynamic capabilities in humanitarian supply chain management: A systematic literature review. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 11, 46–80.

- Ertem, M.A.; İşbilir, M.; Arslan, A.Ş. Review of intermodal freight transportation in humanitarian logistics. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 10.

- Penna, P.H.V.; Santos, A.C.; Prins, C. Vehicle routing problems for last mile distribution after major disaster. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2017, 69, 1254–1268.

- De Camargo, J.A.; Mendonça, P.S.M.; Oliveira, J.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S. Giving voice to the silent: A framework for understanding stakeholders’ participation in socially-oriented initiatives, community-based actions and humanitarian operations projects. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 143–158.

- Mannakkara, S.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. Resilient Post Disaster Recovery through Building Back Better; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018.

- Lopez, A.; de Perez, E.C.; Bazo, J.; Suarez, P.; van den Hurk, B.; van Aalst, M. Bridging forecast verification and human-itarian decisions: A valuation approach for setting up action-oriented early warnings. Weather. Clim. Extrem 2020, 27, 100167.

- Rana, P.; Joshi, S. Management Practices for Sustainable Supply Chain and Its Impact on Economic Performance of SMEs: An Analytical Study of Uttarakhand State, India. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 346–354.

- Janssen, M.; Van Der Voort, H. Agile and adaptive governance in crisis response: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 2020, 55, 102180.

- Dash, P.; Punia, M. Governance and disaster: Analysis of land use policy with reference to Uttarakhand flood 2013, India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 36, 101090.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S. Online Advertisement Using Web Analytics Software. Int. J. Bus. Anal. 2020, 7, 13–33.

- Sigala, I.F.; Kettinger, W.J.; Wakolbinger, T. Digitizing the field: Designing ERP systems for Triple-A humanitarian supply chains. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 10, 231–260.

- Gavidia, J.V. A model for enterprise resource planning in emergency humanitarian logistics. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 7, 246–265.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S. Digital supplier selection reinforcing supply chain quality management systems to enhance firm’s performance. TQM J. 2020.

- Goniewicz, K.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Goniewicz, M.; Naylor, K.; Burkle, F.M., Jr. Current Response and Management Decisions of the European Union to the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3838.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Govindan, K. Issues and solutions of electronic waste urban mining for circular economy transition: An Indian context. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112373.

- Meier, P. Digital Humanitarians: How Big Data is Changing the Face of Humanitarian Response; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A. Assessing enablers of e-waste management in circular economy using DEMATEL method: An Indian perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 13325–13338.

- Gupta, S.; Altay, N.; Luo, Z. Big data in humanitarian supply chain management: A review and further research directions. Ann. Oper. Res. 2019, 283, 1153–1173.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, A. Analysing the Impact of Sustainable Human Resource Management Practices and Industry 4.0 Technologies Adoption on Employability Skills. Int. J. Manpow. 2021. Available online: http://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/6738/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Sharma, M.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A. Implementing challenges of artificial intelligence: Evidence from public manufacturing sector of an emerging economy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 101624.

- Hart, O.E.; Halden, R.U. Modeling wastewater temperature and attenuation of sewage-borne biomarkers globally. Water Res. 2020, 172, 115473.

- Sharma, M.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Kumar, A. Accelerating retail supply chain performance against pandemic disruption: Adopting resilient strategies to mitigate the long-term effects. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2021, 34, 1844–1873.

- Ishiwatari, M.; Koike, T.; Hiroki, K.; Toda, T.; Katsube, T. Managing disasters amid COVID-19 pandemic: Approaches of response to flood disasters. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100096.

- Singh, R.K.; Joshi, S.; Sharma, M. Modelling Supply Chain Flexibility in the Indian Personal Hygiene Industry: An ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC Approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 0972150920923075.

- Bhattacharya, S.; Hasija, S.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Designing Efficient Infrastructural Investment and Asset Transfer Mechanisms in Humanitarian Supply Chains. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 1511–1521.

- Altay, N.; Narayanan, A. Forecasting in humanitarian operations: Literature review and research needs. Int. J. Forecast. 2020.

- Biswal, J.N.; Muduli, K.; Satapathy, S. Critical Analysis of Drivers and Barriers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Indian Thermal Sector. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2017, 10, 411–430.

- Altay, N.; Kovács, G.; Spens, K. The evolution of humanitarian logistics as a discipline through a crystal ball. J. Humanit. Logist. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 11, 577–584.

- Peter, O.; Swain, S.; Muduli, K.; Ramasamy, A. IoT in Combating Covid 19 Pandemics: Lessons for Developing Countries, Assessing COVID-19 and Other Pandemics and Epidemics using Computational Modelling and Data Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 113–132.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S. Brand sustainability among young consumers: An AHP-TOPSIS approach. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 314–337.

- Muduli, K.; Barve, A. Analysis of critical activities for GSCM implementation in mining supply chains in India using fuzzy analytical hierarchy process. Int. J. Bus. Excel. 2015, 8, 767.

- Sharma, M.; Joshi, S.; Kannan, D.; Govindan, K.; Singh, R.; Purohit, H.C. Internet of Things (IoT) adoption barriers of smart cities’ waste management: An Indian context. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 270, 122047.

- Seker, S.; Zavadskas, E.K. Application of Fuzzy DEMATEL Method for Analyzing Occupational Risks on Construction Sites. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2083.

- Prakash, S.; Joshi, S.; Bhatia, T.; Sharma, S.; Samadhiya, D.; Shah, R.R.; Kaiwartya, O.; Prasad, M. Characteristic of enterprise collaboration system and its implementation issues in business management. Int. J. Bus. Intell. Data Min. 2020, 16, 49.

- Kannan, G.; Muduli, K.; Devika, K.; Barve, A. Investigation of influential strength of factors on GSCM adoption in mining in-dustries operating in India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 107, 185–194.

- Brem, A.; Viardot, E.; Nylund, P.A. Implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak for innovation: Which technologies will improve our lives? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120451.

- Fernandez-Luque, L.; Imran, M. Humanitarian health computing using artificial intelligence and social media: A narrative literature review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 114, 136–142.