Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Fungal pigments are produced as secondary metabolites when essential nutrients in the culture medium are depleted or the environment is unfavorable for growth. Since natural pigments have benefits over synthetic pigments, their popularity has grown considerably. It has been demonstrated that fungi are a reliable, accessible, alternative supply of natural pigments. Applications for fungal pigments include food coloring, antimicrobial defense, antioxidant agents, cancer prevention, and so on.

- natural pigments

- carotenoids

- riboflavin

- polyketides

- fungi

1. Pigments as Food Colorants

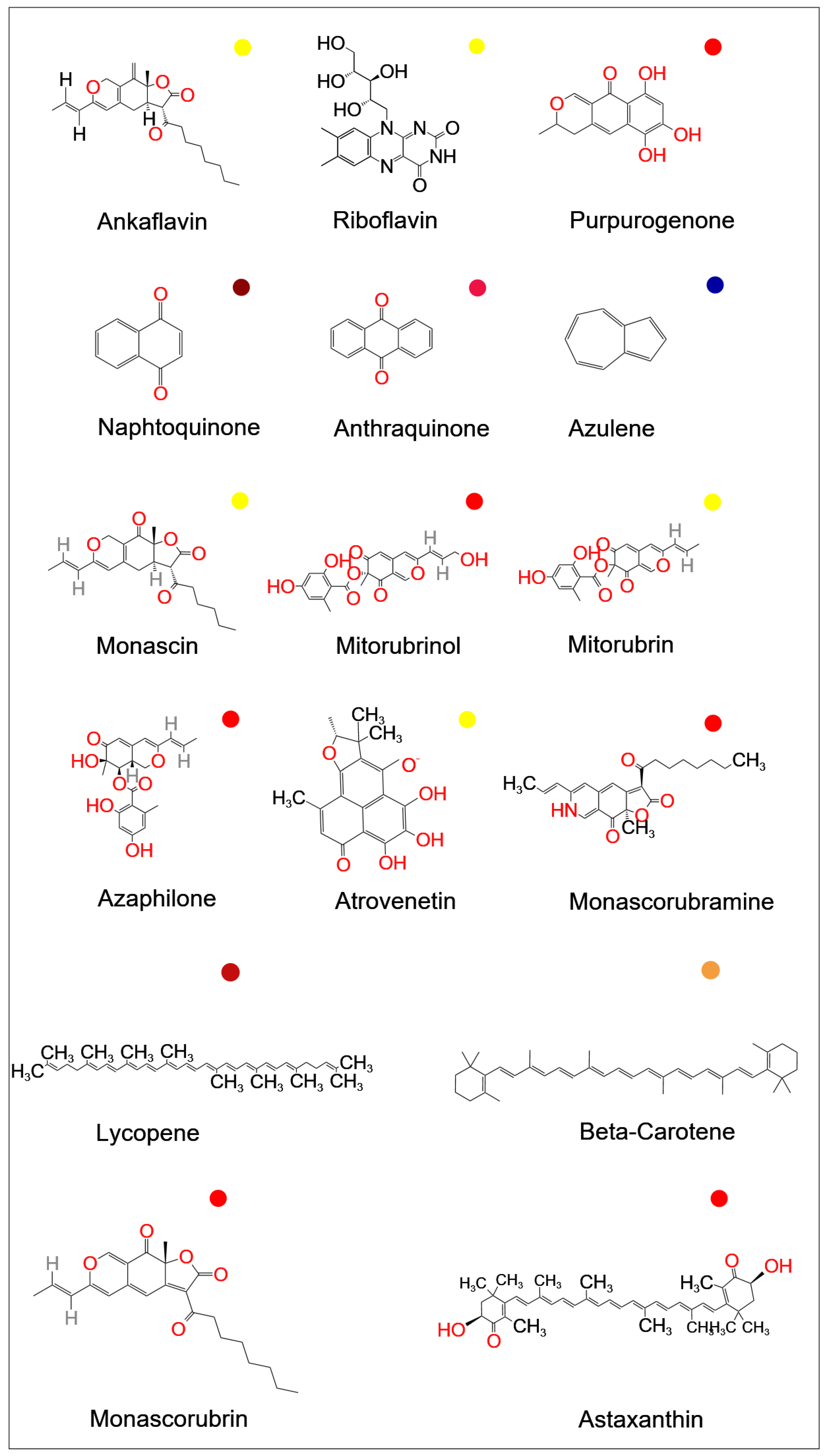

The use of natural colorants enables the replacement of potentially dangerous synthetic dyes [1][2]. Natural pigments are currently used more frequently than that of are chemically synthesized [3]. While red and yellow colorants were once widely employed in food coloring, blue is becoming more and more popular as a food colorant [4]. Polyketide pigments of Monascus, which produce a variety of red, yellow, orange, green, and blue hues, have great potential in this regard [4]. Figure 1 shows the chemical structure of several colorants. The majority of study has focused on the possibility of using fungal pigments in various industries, notably as food colorants or additives in the food industry [5], which has long been known by many researchers [6][7][8].

Figure 1. Chemical structure of some available fungal food pigments (Source: National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov); accessed on 1 April 2023).

Monascus pigments, Arpink red from P. oxalicum, riboflavin from Ashbya gossypii, and β-carotene from B. trispora have already reached the worldwide market as food colorants (Table 1) [6][9]. These fungal pigments also have good commercial production yields. For example, the production yield of β-carotene in a Blakeslea trispora culture medium was reported to be 17 g/L [10][11]. In a study by Abdel-Raheam et al. (2022), Monascus purpureus was employed as an coloring component in ice lollies. The study found that the ice lolly to which these colors were added was highly accepted [12]. Monascus pigments may additionally be applied to other foods, such as fruit-flavored yogurt [13], sweet drops [14], flavored milk [15], jelly beans, and lollipops [16]. Penicillium brevicompactum was identified as a novel source of colors for the food sector in a recent study [17].

Table 1. Some authorized food-grade fungal pigments available in the current global market [17][18].

| Color | E-Number * | Fungal Pigments | Responsible Fungi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow | E101 (iii) | Riboflavin | Ashbya gossypii |

| Orange-yellow | E160a (ii) | Β-carotene | Blakesla trispora |

| Yellow to red | E160d (iii) | Lycopene | Blakesla trispora |

| Yellow/orange/red | E161g | Canthaxanthin | ------------- |

* E-number represents the corresponding authorized food colorants in the European Union.

1.1. Application of Anthraquinones

Penicillium oxalicum produces the anthraquinone pigment Arpink red, a red pigment with bacteriostatic, antiviral, fungicidal, herbicidal, and insecticidal characteristics [19]. Foodstuffs can be supplemented with the Arpink red polyketide of Penicillium oxalicum without any stabilizing [20]. After evaluating the toxicological data of the Arpink red pigment [21], Codex Alimentarius Commmision (CAC) made the statement about the amount to be used in food products (Table 2) that will be non-objectionable [22].

Table 2. Use of anthraquinone (Arpink red) pigment in various food products.

| Sample (Food Products) | Anthraquinone (Amount mg/kg) |

|---|---|

| Milk products | 150 |

| Ice cream | 150 |

| Meat and meat products | 100 |

| Nonalcoholic drinks | 100 |

| Alcoholic drinks | 200 |

| Confectionary products | 300 |

1.2. Application of Azaphilones

The chemical structure of azaphilone has been identified in over 50 distinct ways, and it may readily be coupled with nitrogenous compounds [23]. Monascorubrin, an orange azaphilone pigment derived from Monascus sp., may combine with amino acids to produce a red hue in meals [24]. Again, the polyketide pigments have improved functionality with respect to light stability, water solubility [25], anti-atherogenic activity [26], and antioxidant properties [27] when added to specific food products. As polyketide pigments, azaphilones (red and yellow colorants) of Monascus sp. have been lawfully commercially manufactured and used as food colorants all over the world. In Southeast Asia, a traditionally produced, dry fermented red rice powder has been utilized for over one thousand years [28]. More than 50 patents have recently been issued in several countries, including Japan, the United States, France, and Germany, regarding the use of Monascus pigments in food items [29]. It has been shown that several Talaromyces species, such as T. aculeatus, T. funiculosus, T. pinophilus, and T. purpurogenus, generate azaphilones, Monascus pigment analogues (MPA) pigments, similar to those seen in Monascus without generating citrinin or any other recognized mycotoxins [30].

1.3. Application of Riboflavin

Riboflavin, often known as vitamin B2, is a yellow pigment that is used as a food colorant in most countries and is legal to use. Salad, sherbet, drinks, ice creams, pharmaceuticals, and other goods are among the products in which this pigment is utilized [31]. However, because of its slightly unpleasant smell and bitter taste, its use in cereal-based goods is rather limited, despite the fact that it has an affinity for them. Several bacteria create riboflavin through fermentation. Riboflavin can be divided into three types based on fermentation yield: (i) weak overproducers (100 mg/L or less, e.g., Clostridium acetobutylicum), (ii) moderate overproducers (600 mg/L or more, e.g., Candida guilliermundii or Debaryomyces subglobosus), and (iii) strong overproducers (over 1 g/L). Due to the superior genetic stability of its pigment, Ashbya gossypi is chosen for fermentation over others [32].

2. Pigments as Antimicrobial Agents

Fungal pigments, according to several research studies [33], have numerous health benefits over synthetic pigments, including antibacterial action against a variety of harmful bacteria, yeast, and fungi. The researchers also proposed that these bioactive pigments may be employed in the food and pharmaceutical sectors as food preservatives or antibacterial agents [9][34][35]. It has also been studied whether they may be used to make medical items such as bandages, suture threads, and face masks, and the documented findings imply that it is quite possible [36]. The antimicrobial property of the red pigment generated by M. purpureus was discovered, and the extract of M. purpureus was shown to be 81% effective when compared to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin [37]. Pencolide, sclerotiorin, and isochromophilone were isolated from another fungal strain, P. sclerotiorum, in a large-scale liquid culture. Isochromophilone was found to have antibacterial properties against S. aureus [38]. It was shown that Aspergillus sclertiorum DPUA 585 generated Neoaspergillic acid, which has antibacterial action against Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and Staphylococcus aureus and antifungal activity against C. albicans [39]. Antibacterial activity has also been observed in Aspergillus versicolor [40]. Furthermore, antibacterial activity was found in Penicillium species isolated from Brazilian cerrado soil, with considerable activity against C. albicans, Listeria monocytogenes, and Bacillus cereus, respectively [41]. A key fungus species in the synthesis of many colors is Rhodotorula glutinis. The industrial scale use of this type of yeast has included creating carotenoid colors and acting as a biological control against the post-harvest degradation of fruit [42]. Rhodotorula glutinis pigment may effectively kill both the planktonic type of food-spoilage bacteria and the bacteria that form food-spoilage biofilms [43]. Aspergillus nidulans JAS3, an Indian-Ocean-isolated pigmented fungal strain, was recently the subject of a study that included its extraction, characterization, and antagonistic activity toward clinical pathogens. When strain JAS3 was treated in enhanced Czapek Dox medium at 28 °C, it was discovered that the pigment it produced was of a pale yellow hue. When tested against several clinical pathogenic strains, the colored pigment demonstrated good bioactivity, including antimicrobial, anti-proteinase, and antifouling activities [44]. In another study, a pigment derived from Gonatophrgmium truiniae was found to have antibacterial properties against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Micrococcus luteus [45]. According to Poorniammal and Prabhu (2022), the fungal pigments produced from Thermomyces sp. and Penicillium purpurogenum have antibacterial properties that are effective against Staphylococcus aureus [46].

3. Pigments as Antioxidant Agents

Microbial pigments such as carotenoids, violacein, and naphthoquinones have been shown to have antioxidant properties through several studies. The antioxidant potential of pigments from various fungi has been mentioned in a number of review papers [47][48][49]. Studies on the antioxidant activity of pigments from several fungi, including Penicillium sp. (P. miczynskii, P. purpureogenum, P. purpuroscens), Fusarium sp., Thermomyces sp., Chaetomium sp., Sanghuangporus baumii, Stemphylium lycopersici, and Trichoderma sp. (T. afroharzianum) have revealed their promising antioxidant potential and their possible application in the healthcare industry [50]. Epicoccum nigrum has also been demonstrated to be a non-mycotoxigenic fungal producer of a polyketide pigment with antioxidant properties [30]. The extracted pigment generated by Monascus purpureus in the investigation. Zeng et al. (2021) showed a stronger antioxidant activity in scavenging free radicals and preventing lipid oxidation [51]. In the study by Nair and Abraham (2023), it was revealed that a pale yellow pigment produced by Aspergillus nidulans JAS3 demonstrated antioxidant activity [44]. In another study, Phoma sp. RDSE17 was isolated and characterized for its melanin pigment. The biological characteristics of the pure melanin of the fungus were examined for their antioxidant activities. The pure melanin demonstrated strong DPPH free-radical-scavenging activity with an EC50 of 69 µg/mL [52]. In the study by Fonseca et al. (2022), natural pigments derived from Penicillium brevicompactum were tested and found to be mycotoxin-free with potential antioxidant action [52]. Extracellular fungi pigments from Penicillium murcianum and Talaromyces australis demonstrated biotechnological potential of antioxidant activities in a study [53]. In another study, Gonatophrgmium truiniae’s pigment demonstrated antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 0.99 mg/mL [54].

4. Pigments as Anticancer Agents

Fungal pigments have been shown to have anticancer and antitumor effects. Several investigations have indicated that fungal pigments might be used as an anticancer medication. Pigments of Monascus species (M. purpureus and M. pilosus) such as monascin, ankaflavin, monaphilone A–B, monapilol A–D, and monapurone A–C have been shown to have anticancer/antitumor potential against various cancers, including mouse skin carcinoma, human laryngeal carcinoma, human colon adenocarcinoma, and human hepatocellular carcinoma [28]. In addition to Monascus, other fungal pigments with anticancer, antitumor, or antiproliferative activities include norsolorinic acid from A. nidulans, shiraiarin from Shiraia bambusicola, alterporriol K, alterporriol L, and alterporriol M from Alternaria sp., benzoquinone from Fusarium sp., and an uncharacterized red pigment F (MCF-7, MDA-MB-435, and MCF-7 b), whereas hypocrellin D from S. bambusicola has anticancer effects against many other cancer cell lines (Bel-7721, A-549, and Anip-973) [55][56]. As an example, the anticancer properties of the AUMC 5705 Monascus strain as well as that of the AUMC 4066 secondary metabolites, which have numerous uses in the food, pharmaceutical, and other sectors, are evident [57]. The anticancer potentiality of raw coix seed fermented by Monascus purpureus was demonstrated and observed thatthe HEp2 cell line of human laryngeal carcinoma, which makes up 25% of neck and head cancers, was used to test the extract’s anticancer potential [51]. In another study, 80 µg/mL of pure melanin extracted from Phoma sp. RDSE17 hindered the development of human lung cancer cells [52].

5. Pigments Used in Pharmaceuticals

Sclerotiorin, a bioactive metabolite generated by P. sclerotiorum, has been utilized in the pharmaceutical sector [58]. Penicillium sp. NIMO-02 produces a pigment that is important in the food and pharmaceutical sectors [59]. P. purpurogenum generated greater extracellular pigments with antibacterial activity in darkness, which may be used in the pharmaceutical and healthcare industries [60], while Trichoderma virens has eco-friendly antifungal characteristics. Penicillium sp. generates various secondary metabolites with high bioactive chemicals; these are utilized in pharmacy to make medicines to treat a variety of ailments and in agriculture [61]. P. oxalicum var. Armeniaca CCM 8242 generated an anthraquinone chromophore. The anthraquinone derivative Arpink red possesses anticancer properties and is used in food and medicines [62][63]. Sorbicillinoid pigments from Stagonospora sp. SYSU-MS7888 demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity in a recent research study [64]. The effectiveness of a purified anthraquinone from Talaromyces purpureogenus as a powerful agent for kidney radio-imaging, which might be used in the diagnosis of kidney cancer, was demonstrated [64]. As intriguing alternative medication sources, several instances of true endophytic fungi generating anthraquinones similar to their various host plants have been documented [65]. A pale yellow pigment produced by Aspergillus nidulans JAS3 was found to have anti-inflammatory activities [44]. According to another study, cadmium can be reduced with melanin pigment derived from Aspergillus terreus LCM8 [66].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jof9040454

References

- Echegaray, N.; Guzel, N.; Kumar, M.; Guzel, M.; Hassoun, A.; Lorenzo, J.M. Recent advancements in natural colorants and their application as coloring in food and in intelligent food packaging. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134453.

- Aman Mohammadi, M.; Ahangari, H.; Mousazadeh, S.; Hosseini, S.M.; Dufossé, L. Microbial pigments as an alternative to synthetic dyes and food additives: A brief review of recent studies. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 1–12.

- Nawaz, A.; Chaudhary, R.; Shah, Z.; Dufossé, L.; Fouillaud, M.; Mukhtar, H.; Haq, I.U. An Overview on Industrial and Medical Applications of Bio-Pigments Synthesized by Marine Bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 11.

- Mapari, S.A.; Meyer, A.S.; Thrane, U. Colorimetric characterization for comparative analysis of fungal pigments and natural food colorants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 7027–7035.

- Dufossé, L.; Fouillaud, M.; Caro, Y.; Mapari, S.A.; Sutthiwong, N. Filamentous fungi are large-scale producers of pigments and colorants for the food industry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 26, 56–61.

- Caro, Y.; Venkatachalam, M.; Lebeau, J.; Fouillaud, M.; Dufossé, L. Pigments and colorants from filamentous fungi. In Fungal Metabolites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 499–568.

- Mapari, S.A.; Thrane, U.; Meyer, A.S. Fungal polyketide azaphilone pigments as future natural food colorants? Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 300–307.

- Simpson, B.K.; Nollet, L.M.; Toldrá, F.; Benjakul, S.; Paliyath, G.; Hui, Y. Food Biochemistry and Food Processing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012.

- Kim, D.; Ku, S. Beneficial Effects of Monascus sp. KCCM 10093 Pigments and Derivatives: A Mini Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 98.

- Dufossé, L. Pigments, Microbial; Reference Module in Life Sciences; University of Reunion Island: Saint-Denis, France, 2016.

- Torres, F.A.E.; Zaccarim, B.R.; de Lencastre Novaes, L.C.; Jozala, A.F.; Dos Santos, C.A.; Teixeira, M.F.S.; Santos-Ebinuma, V.C. Natural colorants from filamentous fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2511–2521.

- Abdel-Raheam, H.E.; Alrumman, S.A.; Gadow, S.I.; El-Sayed, M.H.; Hikal, D.M.; Hesham, A.E.L.; Ali, M.M. Optimization of Monascus purpureus for Natural Food Pigments Production on Potato Wastes and Their Application in Ice Lolly. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 862080.

- Abdel-Raheam, H.E.F.; Abdel-Mageed, W.S.; Abd El-Rahman, M.A.M. Optimization of production of Monascus ruber pigments on broth medium and their application in flavored yogurts. Egypt. J. Food Sci. 2019, 47, 271–283.

- Abdel-Raheam, H.E.F.; Hassan, S.H.A.; Ali, M.M.A. Production and application of natural food pigments by Monascus ruber using potato chips manufacturing wastes. Bull. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 44, 551–563.

- Gomah, N.H.; Abdel-Raheam, H.E.F.; Mohamed, T.H. Production of Natural Pigments from Monascus ruber by Solid State Fermentation of Broken Rice and its Application as Colorants of Some Dairy Products. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2017, 8, 37–43.

- Darwesh, O.M.; Matter, I.A.; Almoallim, H.S.; Alharbi, S.A.; Oh, Y.-K. Isolation and Optimization of Monascus ruber OMNRC45 for Red Pigment Production and Evaluation of the Pigment as a Food Colorant. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8867.

- Scotter, M. Overview of EU regulations and safety assessment for food colours. In Colour Additives for Foods and Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015.

- Caro, Y.; Anamale, L.; Fouillaud, M.; Laurent, P.; Petit, T.; Dufossé, L. Natural hydroxyanthraquinoid pigments as potent food grade colorants: An overview. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2012, 2, 174–193.

- Gessler, N.N.; Egorova, A.S.; Belozerskaya, T.A. Fungal anthraquinones. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2013, 49, 85–99.

- Takahashi, J.; Carvalho, S. Nutritional potential of biomass and metabolites from filamentous fungi. Curr. Res. Technol. Educ. Top. Appl. Microbiol. Microb. Biotechnol. 2010, 2, 1126–1135.

- Sardaryan, E.; Zihlova, H.; Strnad, R.; Cermakova, Z. Arpink Red–meet a new natural red food colorant of microbial origin. In Pigments in Food, More than Colours; Université de Bretagne Occidentale: Quimper, France, 2004; pp. 207–208.

- Kumar, A.; Vishwakarma, H.S.; Singh, J.; Dwivedi, S.; Kumar, M. Microbial pigments: Production and their applications in various industries. Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Biol. Sci. 2015, 5, 203–212.

- Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Du, X.; Li, P.; Liang, B.; Cheng, X.; Du, L.; Huang, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Complete genome sequence and transcriptomics analyses reveal pigment biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms in an industrial strain, Monascus purpureus YY-1. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8331.

- Jung, H.; Kim, C.; Kim, K.; Shin, C.S. Color characteristics of Monascus pigments derived by fermentation with various amino acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1302–1306.

- Jung, H.; Kim, C.; Shin, C.S. Enhanced photostability of Monascus pigments derived with various amino acids via fermentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 7108–7114.

- Jeun, J.; Jung, H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, Y.O.; Youn, S.H.; Shin, C.S. Effect of the monascus pigment threonine derivative on regulation of the cholesterol level in mice. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1078–1085.

- Yang, J.-H.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.-L.; Mau, J.-L. Antioxidant properties of methanolic extracts from monascal rice. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 740–747.

- Feng, Y.; Shao, Y.; Chen, F. Monascus pigments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 1421–1440.

- Hajjaj, H.; Klaébé, A.; Goma, G.; Blanc, P.J.; Barbier, E.; François, J. Medium-Chain Fatty Acids Affect Citrinin Production in the Filamentous Fungus Monascus ruber. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 1120–1125.

- Mapari, S.A.; Meyer, A.S.; Thrane, U.; Frisvad, J.C. Identification of potentially safe promising fungal cell factories for the production of polyketide natural food colorants using chemotaxonomic rationale. Microb. Cell Factories 2009, 8, 24.

- Stahmann, K.-P.; Revuelta, J.; Seulberger, H. Three biotechnical processes using Ashbya gossypii, Candida famata, or Bacillus subtilis compete with chemical riboflavin production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 53, 509–516.

- Santos, M.A.; Mateos, L.; Stahmann, K.-P.; Revuelta, J.-L. Insertional mutagenesis in the vitamin B2 producer fungus Ashbya gossypii. In Microbial Processes and Products; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005.

- Akilandeswari, P.; Pradeep, B. Exploration of industrially important pigments from soil fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1631–1643.

- Wang, W.; Chen, R.; Luo, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, J. Antimicrobial activity and molecular docking studies of a novel anthraquinone from a marine-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 558–563.

- Wang, W.; Liao, Y.; Chen, R.; Hou, Y.; Ke, W.; Zhang, B.; Gao, M.; Shao, Z.; Chen, J.; Li, F. Chlorinated azaphilone pigments with antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities isolated from the deep sea derived fungus Chaetomium sp. NA-S01-R1. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 61.

- Parthiban, M.; Thilagavathi, G.; Viju, S. Development of antibacterial silk sutures using natural fungal extract for healthcare applications. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2016, 6, 249.

- Kumar, S.; Verma, U.; Sharma, H. Antibacterial activity Monascus purpureus (red pigment) isolated from rice malt. Asian J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 1, 252–255.

- Lucas, E.M.; Castro, M.C.; Takahashi, J.A. Antimicrobial properties of sclerotiorin, isochromophilone VI and pencolide, metabolites from a Brazilian cerrado isolate of Penicillium sclerotiorum Van Beyma. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2007, 38, 785–789.

- Teixeira, M.F.; Martins, M.S.; Da Silva, J.C.; Kirsch, L.S.; Fernandes, O.C.; Carneiro, A.L.; Da Conti, R.; Durán, N. Amazonian biodiversity: Pigments from Aspergillus and Penicillium-characterizations, antibacterial activities and their toxicities. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 2012, 6, 300–311.

- Miao, F.-P.; Li, X.-D.; Liu, X.-H.; Cichewicz, R.H.; Ji, N.-Y. Secondary Metabolites from an Algicolous Aspergillus versicolor Strain. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 131–139.

- Petit, P.; Lucas, E.M.F.; Abreu, L.M.; Pfenning, L.H.; Takahashi, J.A. Novel antimicrobial secondary metabolites from a Penicillium sp. isolated from Brazilian cerrado soil. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 12, 8–9.

- Poorniammal, R.; Prabhu, S.; Dufossé, L.; Kannan, J. Safety Evaluation of Fungal Pigments for Food Applications. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 692.

- Naisi, S.; Bayat, M.; Salehi, T.Z.; Zarif, B.R.; Yahyaraeyat, R. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm effects of carotenoid pigment extracted from Rhodotorula glutinis strain on food-borne bacteria. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2023, 15, 79–88.

- Nair, S.; Abraham, J. Biosynthesis and characterization of yellow pigment from Aspergillus nidulans strain JAS3 isolated from Thirumullavaram, Indian Ocean and its therapeutic activity against clinical pathogens. Biologia 2023, 78, 1171–1185.

- Lagashetti, A.C.; Dufossé, L.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, P.N. Fungal Pigments and Their Prospects in Different Industries. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 604.

- Poorniammal, R.; Prabhu, S. Antimicrobial and wound healing potential of fungal pigments from Thermomyces sp. and Penicillium purpurogenum in wistar rats. Ann. Phytomed. Int. J. 2022, 11, 376–382.

- Ramesh, C.; Vinithkumar, N.V.; Kirubagaran, R.; Venil, C.K.; Dufossé, L. Multifaceted applications of microbial pigments: Current knowledge, challenges and future directions for public health implications. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 186.

- Rao, M.P.N.; Xiao, M.; Li, W.-J. Fungal and Bacterial Pigments: Secondary Metabolites with Wide Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1113.

- Vendruscolo, F.; Bühler, R.M.M.; de Carvalho, J.C.; de Oliveira, D.; Moritz, D.E.; Schmidell, W.; Ninow, J.L. Monascus: A reality on the production and application of microbial pigments. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 178, 211–223.

- Poorniammal, R.; Prabhu, S.; Sakthi, A. Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant activity of fungal pigments. J. Pharma. Innov. 2019, 8, 326–330.

- Zeng, H.; Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Miao, S. Increases of Lipophilic Antioxidants and Anticancer Activity of Coix Seed Fermented by Monascus purpureus. Foods 2021, 10, 566.

- Fonseca, C.S.; da Silva, N.R.; Ballesteros, L.F.; Basto, B.; Abrunhosa, L.; Teixeira, J.A.; Silvério, S.C. Penicillium brevicompactum as a novel source of natural pigments with potential for food applications. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 132, 188–199.

- Contreras-Machuca, P.I.; Avello, M.; Pastene, E.; Machuca, Á.; Aranda, M.; Hernández, V.; Fernández, M. Chemical characterization and microencapsulation of extracellular fungal pigments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 8021–8034.

- Pimenta, L.; Gomes, D.; Cardoso, P.; Takahashi, J. Recent Findings in Azaphilone Pigments. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 541.

- Zheng, L.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, L.; Huang, P.; Ren, X.; Zuo, A.; Meng, X.; Xu, M.; Liao, X. Benzoquinone from Fusarium pigment inhibits the proliferation of estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 cells through the NF-κB pathway via estrogen receptor signaling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 39–46.

- Soumya, K.; Narasimha Murthy, K.; Sreelatha, G.; Tirumale, S. Characterization of a red pigment from Fusarium chlamydosporum exhibiting selective cytotoxicity against human breast cancer MCF-7 cell lines. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 148–158.

- Moharram, A.M.; Mostafa, M.E.; Ismail, M.A. Chemical profile of Monascus ruber strains. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 50, 490–499.

- Lucas, E.; Machado, Y.; Ferreira, A.; Dolabella, L.; Takahashi, J. Improved production of pharmacologically-active sclerotiorin by Penicillium sclerotiorum. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2010, 9, 365–371.

- Dhale, M.A.; Vijay-Raj, A.S. Pigment and amylase production in Penicillium sp NIOM-02 and its radical scavenging activity. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 2424–2430.

- Geweely, N.S. Investigation of the optimum condition and antimicrobial activities of pigments from four potent pigment-producing fungal species. J. Life Sci. 2011, 5, 201.

- Tajick, M.A.; Seid Mohammad Khani, H.; Babaeizad, V. Identification of biological secondary metabolites in three Penicillium species, P. goditanum, P. moldavicum, and P. corylophilum. Prog. Biol. Sci. 2014, 4, 53–61.

- Dufossé, L. Microbial production of food grade pigments. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 44, 313–323.

- Chen, S.; Guo, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, M.; Li, H.; Liu, L. Targeted Discovery of Sorbicillinoid Pigments with Anti-Inflammatory Activity from the Sponge-Derived Fungus Stagonospora sp. SYSU-MS7888 Using the PMG Strategy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 15116–15125.

- Hasanien, Y.A.; Nassrallah, A.A.; Zaki, A.G.; Abdelaziz, G. Optimization, purification, and structure elucidation of anthraquinone pigment derivative from Talaromyces purpureogenus as a novel promising antioxidant, anticancer, and kidney radio-imaging agent. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 356, 30–41.

- Shakour, Z.T.; Farag, M.A. Diverse host-associated fungal systems as a dynamic source of novel bioactive anthraquinones in drug discovery: Current status and future perspectives. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 39, 257–273.

- Hayat, R.; Din, G.; Farooqi, A.; Haleem, A.; Din, S.U.; Hasan, F.; Badshah, M.; Khan, S.; Shah, A.A. Characterization of melanin pigment from Aspergillus terreus LCM8 and its role in cadmium remediation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 20, 3151–3160.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!