1. Introduction

[

18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose ([

18F]FDG), as a tracer to detect and characterize infections and inflammatory disorders, has been considered to be a major drawback since it leads to false-positive results in patients with cancer [

7]. However, over recent years, [

18F]FDG has been adopted as a powerful modality for detecting sites of inflammation including bacterial infections [

7]. Currently, it is well established that inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages have a high concentration of glucose transporters in their cell membranes, enhancing cellular glucose metabolism [

7]. Furthermore, circulating cytokines during inflammation also seem to increase the affinity of these transporters [

7]. Hence, [

18F]FDG remains to be one of the most studied and commonly used radiotracers for diagnosing human infection and inflammation [

4] (

Figure 1). Due to its versatility, [

18F]FDG has been appropriately referred to as the ‘‘molecule of the century’’ owing to its enormous impact on the day-to-day practice of medicine [

8].

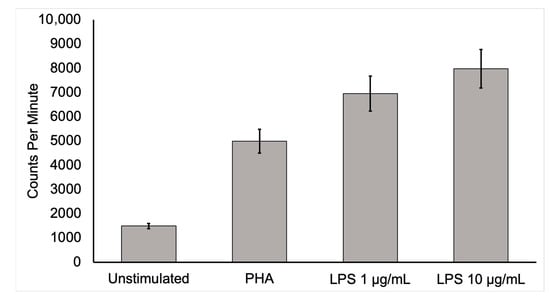

Figure 1. Activated mononuclear cell deoxyglucose uptake. To show that activated inflammatory cells have a higher uptake of [18F]FDG, human mononuclear cells from a healthy, adult male were isolated and cultured for 6 h in media containing [3H]deoxyglucose ([3H]DG) in the absence of stimulants and in the presence of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or phytohemagglutinin (PHA). After culture, samples were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline, collected, and placed in a scintillation counter. Mononuclear cells uptake of [3H]DG was several times more in the stimulated state than in the unstimulated control condition. This in vitro study supports the conclusion that active inflammatory cells dramatically increase [18F]FDG uptake. Moreover, highly increased [18F]FDG uptake by activated inflammatory cells at infection sites is likely to allow the detection of infection by this technique.

With the introduction of combined PET/computed tomography (CT) in 2001, PET/CT has become one of the most widely used imaging techniques for diagnosing infectious and inflammatory disorders [

4]. However, [

18F]FDG, as the molecular imaging test of choice for many inflammatory and infectious indications (including sarcoidosis, fever of unknown origin, and musculoskeletal infection), was only recently approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in the United States [

9]. All along, there has been a growing interest in exploring the usefulness of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT in many infectious and inflammatory disorders beyond its original research trials [

10]. The clinical use of PET imaging is being widely studied for chronic osteomyelitis, complicated lower-limb prostheses, complicated diabetic foot, fever of unknown origin, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), vascular graft infection, and fistula, among various other indications [

10].

2. State of [18F]FDG-PET Imaging in Fever of Unknown Origin

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) was defined in 1961 as a disease condition where body temperature exceeds 38.3 °C on at least three occasions over three weeks, with no diagnosis made despite one week of investigations in the hospital [

11]. In the report by Petersdorf and Beeson, the causes of FUO with more than 200 identified diagnoses were classified as infection (36%), malignancy (19%), collagen vascular diseases (19%), and miscellaneous (19%), with no cause found in some cases (7%) [

12].

Although it was defined and classified more than 50 years ago, FUO still presents a challenge in diagnosis due to the lack of a specific diagnostic algorithm. The wide range of clinical presentations with diversity in probable causes has also added to the challenge in diagnosis. [

18F]FDG-PET/CT, with its ability to detect both metabolic and structural details of the cause of FUO, can be used as the diagnostic modality of choice for FUO [

11]. Furthermore, as metabolic changes occur earlier than morphological changes during inflammation, [

18F]FDG PET/CT also has the added benefit of identifying areas of inflammation at their early stages as compared with other diagnostic modalities [

13]. Moreover, the recently introduced, total-body PET imaging has the additional advantage of increased sensitivity even with a relatively low radiation exposure when compared to a CT scan. [

18F]FDG-PET has been shown to have a high sensitivity in the workup of FUO [

14]. The diagnostic accuracy of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT reaches 89% when performed in cases of FUO with increased c-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels [

15]. A retrospective study also found that [

18F]FDG-PET/CT was used in the confirmation of suspected causes of FUO in 56.6% of cases, with infection accounting for 21%, malignancy accounting for 22%, noninfectious inflammatory diseases accounting for 12%, others accounting for 5%, and the cause unknown in 40% [

16,

17]. To date, there has been a very wide range of applications of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT. It has been utilized in the detection of infective endocarditis [

16] as well as prosthetic valve endocarditis [

16,

17]. Furthermore, it has been applied in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis [

18] and cranial giant cell arteritis [

19].

Two studies were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT in diagnosing FUO. The first study, a meta-analysis, found that using [

18F]FDG-PET/CT resulted in a high rate of negative predictive values and improved the overall diagnostic rate for FUO [

5]. The second study, conducted by Pereira et al., found that [

18F]FDG-PET/CT was able to confirm the cause of FUO in 56.6% of cases, with causes ranging from infection, malignancy, and non-infectious inflammatory disease to other factors and unknown causes. These studies indicate that [

18F]FDG-PET/CT is an effective tool for diagnosing FUO and may provide more accurate diagnoses in many cases.

In many recent studies, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT has proven to be a highly sensitive diagnostic tool for FUO. When comparing it to other conventional diagnostic modalities used currently for the diagnosis of FUO, it has been found to have better sensitivity and specificity, along with its use in the detection and localization of the lesions [

5,

13,

20]. Furthermore, it can be adapted for use in monitoring and evaluating the treatment response. [

18F]FDG-PET/CT is comparably inexpensive compared to other nuclear imaging studies and has the advantage of providing results on the same day; hence, it can be more cost-effective as it can help to avoid unnecessary invasive tests while decreasing the hospital stay [

15,

21].

3. State of [18F]FDG-PET Imaging in Cardiovascular Infections

[

18F]FDG-PET/CT has been found to play a role in the evaluation of endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis. Transthoracic echocardiography along with blood culture has traditionally been a diagnostic modality of choice for detecting cardiovascular infections such as infective endocarditis (IE) [

22]; IE poses a diagnostic dilemma due to its very diverse clinical presentation. The current method of diagnosis uses modified Duke criteria (MDC), which are divided into “major criteria” (typical blood culture and positive echocardiography) and “minor criteria” (predisposition, fever, vascular phenomena, immunologic phenomena, suggestive echocardiogram, and suggestive microbiologic findings). However, it creates a problem for patients with equivocal clinical symptoms in the absence of conventional echocardiographic features (particularly when prosthetic heart valves are present), making the diagnosis difficult [

23]. Imaging modalities such as transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been studied. However, a number of technical factors, which include the presence of prosthetic heart valves and the aortic graft, prevent these imaging modalities from being accurate and reliable. PET/CT has demonstrated an advantage over echocardiography, especially in prosthetic valve endocarditis, but its role in native valve endocarditis is still unclear [

24,

25,

26]. In such patients, when [

18F]FDG-PET/CT is combined with MDC, the sensitivity of IE diagnosis appears to increase [

27,

28]. Additionally, there has also been an improvement in the diagnosis of symptomatic or asymptomatic septic embolism [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The detection of a septic embolism has also helped to change the therapeutic decision as its presence necessitates a longer duration of antibiotic treatment or timely surgical consultation. Furthermore, compared to PET/CT, PET/CT-angiography is able to detect considerably more abscesses and collections, as well as numerous lesions that are important for clinical and surgical decision-making [

32]. However, leukocyte scintigraphy appears to be advantageous over [

18F]FDG-PET/CT in the first 2 months post open cardiac surgery due to the possibility of a high and comparable level of radiotracer uptake in the inflammatory tissues [

33].

The most common cause of myocarditis is infection, especially viral infections [

22]. Creatine kinase MB-muscle and brain (CK-MB) and troponin-I have high specificity but lack sensitivity in diagnosing myocarditis [

35,

36]. Similarly, echocardiography also has less sensitivity and can show either normal heart function or global/regional left ventricular hypokinesis [

37]. [

18F]FDG-PET/CT can be a useful diagnostic tool as it can demonstrate increased metabolic activity in the myocardium [

38]. Radiation exposure also decreases with PET/MR as compared to PET/CT. [

18F]FDG-PET findings could provide complementary and additive benefits to cardiac MR by increasing sensitivity for mild or borderline myocarditis and increasing specificity for chronic myocarditis [

38,

39].

Viral pericarditis is the most common cause of acute pericarditis. The presence of associated pericardial effusion and concomitant myocarditis can be detected using echocardiography and cardiac MRI [

40]. [

18F]FDG-PET/CT can also detect the inflammation correlating with cardiac MRI in those cases [

41]. However, with quick assessment and decision-making, CT and echocardiography are more beneficial in the diagnosis of viral, bacterial, and fungal pericarditis than PET/CT [

42]. Interestingly, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT can be superior to CT in detecting tuberculous pericarditis [

43]. As shown in a study of nine patients, dual-phase [

18F]FDG PET/CT identified 18 sites of associated lymph node involvement, among which 9 sites were not identified on CT [

43]. Furthermore, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT can also be useful in the diagnosis of metastatic infection in purulent pericarditis with septicemia [

42].

4. Role of [18F]FDG-PET/CT in Musculoskeletal Infections

Imaging methods are part of the diagnostic workup for musculoskeletal infections, which are often challenging diagnoses. Although gallium-67, labeled leukocytes, and bone imaging with radionuclides are the most often used techniques in this context, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT may play an essential role in the clinical diagnosis of acute, subacute, and chronic bone marrow and soft tissue infections. Compared to traditional radionuclide procedures, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT offers the advantage of locating abnormalities more precisely, and monitoring response to treatment [

44].

The role of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT has been found to be promising in a number of musculoskeletal infectious disorders. [

18F]FDG-PET/CT is important for diagnosing persistent musculoskeletal infections [

45] including the detection of chronic osteomyelitis [

46]. Some other uses of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT may include evaluation of the diabetic foot [

47], implant-related infections in the leg [

48], and septic arthritis [

44,

49,

50,

51,

52].

Numerous molecular imaging techniques have been used to diagnose and evaluate treatment responses in patients with osteomyelitis. Commonly used radiopharmaceuticals such as combined bone marrow/leukocyte scintigraphy, gallium scintigraphy, combined [

99mTc]-methyl diphosphonate ([

99mTc]MDP) bone/gallium scintigraphy, and combined [

99mTc]MDP bone/leukocyte scintigraphy have significant limitations in this context, which can be overcome by using [

18F]FDG PET/CT [

53]. [

18F]FDG-PET has shown higher sensitivity (96%) and specificity (91%) in chronic osteomyelitis compared to a bone scan, leukocyte scan, and a combined bone/leukocyte scan and MRI [

10]. Moreover, when it comes to differentiating chronic osteomyelitis (duration > 6 months) from aseptic post-operative/traumatic bone healing, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT plays an important role. [

18F]FDG uptake persists in chronic osteomyelitis, since activated macrophages continue to accumulate [

18F]FDG in chronic infection [

54,

55].

One of the important domains where [

18F]FDG-PET/CT is definitely helpful is in the diagnosis of spinal osteomyelitis. [

18F]FDG-PET has higher diagnostic accuracy for the detection of vertebral chronic osteomyelitis compared to a leukocyte scan [

10]. In addition, [

18F]FDG-PET has the advantage of being less susceptible to attenuation or metal artifacts due to implants compared to structural imaging modalities [

56]. However, care must be taken while differentiating chronic osteomyelitis from false positive results on [

18F]FDG-PET/CT due to fractures, inflammatory arthritis, or normal bone healing after surgery. Due to its high negative predictive value, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT has also been found to be a useful addition to MRI for differentiating degenerative and infectious end plate abnormalities [

1]. Notably, degenerative changes exhibit only mildly elevated [

18F]FDG uptake [

57].

The role of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT in the evaluation of diabetic foot infection remains unclear, with some researchers finding great accuracy and others reporting the exact opposite [

44]. It is crucial to distinguish between osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot and neuropathic osteoarthropathy, since their respective treatments differ. Neuropathic osteoarthropathy demonstrates a lower [

18F]FDG metabolism than osteomyelitis [

47,

58]. In a study of 39 patients with a clinically suspected diabetic foot infection, [

18F]FDG-PET/CT demonstrated good sensitivity (100%), specificity (92%), PPV (87%), and NPV (95%). However, the diagnostic accuracy of leukocyte scans was shown to be superior to that of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT in another study [

59]. Presumably, variability in serum glucose level prior to the [

18F]FDG-PET/CT exam (which is a regular occurrence in diabetic patients) may account for the contradictory results [

53].

The role of [

18F]FDG-PET/CT in prosthetic joint infection is somewhat established but may require further validation [

53]. In addition, the role of [

18F]FDG PET/CT in the clinical differentiation of prosthetic joint infection from displacement/aseptic loosening is also not clear. Peri-prosthetic [

18F]FDG activity in the prosthesis-bone interface is very specific for infection [

60,

61] and has high sensitivity and specificity [

62,

63,

64,

65]. In contrast, non-specific uptake is seen around the femoral neck as an inflammatory reaction [

57].

Few studies exist regarding the usefulness of [

18F]FDG-PET in septic arthritis. [

18F]FDG accumulates in inflammatory arthritis, and its diagnostic usefulness in septic arthritis is likely limited [

44,

49,

50,

51,

52].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics13071231