Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Materials Science, Biomaterials

Jordan is considered to be a semi-desert and steppe area, especially in southern and eastern lands, known as the Jordanian steppe or Badia. Bioenergy has all of the characteristics required to meet the difficulties associated with the increasing use of carbon fuels whereas massively minimizing GHG emissions.

- bioenergy

- biomass

- nanotechnology

- biofuels

- biogas

- biodiesel

1. Introduction

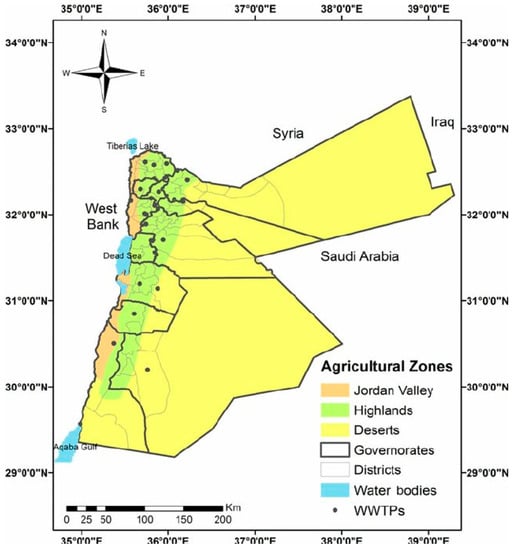

Jordan is considered to be a semi-desert and steppe area [27], especially in southern and eastern lands [28], known as the Jordanian steppe or Badia [27]. Jordan’s natural resources are limited, as illustrated in Figure 1 [29]. Jordan’s energy situation is critical; as a result, Jordan primarily relies on fossil fuel imports to meet its energy needs. Energy is regarded as the most significant impediment to the growth of Jordan’s industrial sectors; bioenergy may help to solve this critical issue. Jordan’s policy debate is now focused on energy security. Authorities and the general public are both aware of the need to develop strategies for achieving long-term energy security, diversifying energy and import sources, and increasing the share of domestic sources [30]. Historical developments have shaped Jordan’s energy market, and reviewing them could assist in better comprehending the strategies and options that are currently being considered to meet the country’s growth. Jordan’s reliance on fossil fuels was reinforced in the 1990s energy needs. Until 2002, Jordan relied almost entirely on Iraq to import low-cost crude oil and its derivatives [31]. Iraq supplied crude oil to Jordan for about one-third of its market value under Saddam Hussein and also permitted Jordan to compensate in consumer goods [32]. Jordan also met its energy demands by importing power from Syria and Egypt [33]. With the 2003 Iraq War and the demise of Saddam Hussein’s regime, Jordan might no longer rely on Iraq to meet its oil needs and began importing oil at market prices, primarily from Saudi Arabia. Following the steady rise in global oil prices, the energy bill began to rise. To reduce expenses, Jordan has begun importing liquefied natural gas from Egypt via the Arab Pipeline, which went into effect in 2003 [30].

Figure 1. Map of the Jordanian desert, Badia, and agricultural zones.

2. Bioenergy

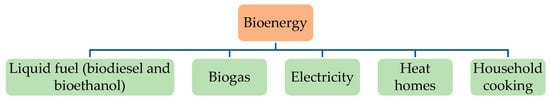

Bioenergy has all of the characteristics required to meet the difficulties associated with the increasing use of carbon fuels whereas massively minimizing GHG emissions [17]. The methods and technologies used to generate bioenergy differ by country [21]. Figure 2 shows the main types of bioenergy [36].

Figure 2. Mainly types of bioenergy.

3. Potential Bioenergy Supply in Jordan

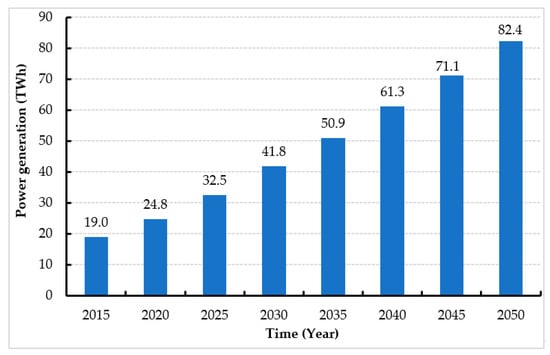

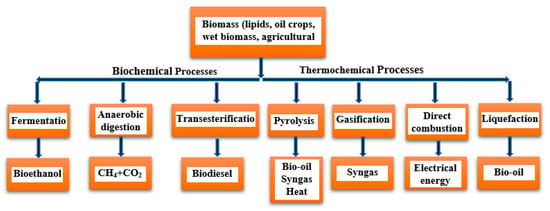

Jordan primarily relies on imports to meet the country’s ever-increasing energy demands [22,157]. Jordan’s electricity demands have dramatically increased, as illustrated in Figure 7, and are expected to reach 82.4 TWh by 2050 [10]. Figure 8 shows that bioenergy can be a highly beneficial, clean technology that could solve the energy issues in Jordan [36]. Jordan aims to increase the contribution of RE to 11% by 2025 [158].

Figure 7. Jordan’s electricity requirements between 2015 and 2050.

Figure 8. General bioenergy production scheme.

3.1. Potential Bioenergy from Crop Residues in Jordan

3.1.1. Biofuel from Corn Leaf Waste in Jordan

There are many large corn farms in Jordan Valley, located in the western area of Jordan. Thus, there is a large amount of corn waste in the form of stalks, leaves, husks, and cobs. Amer et al. [63] concluded that many feedstocks could be used to produce biofuels, such as straws, rice husks, corn leaves and stovers, and wheat straws. However, in terms of dry basis, corn leaf waste in Jordan has a chemical content as described in Table 9. It has slightly higher C, N, and S contents compared to average corn leaf wastes from China, Pakistan, and Brazil (C: 36.6–47.0; N: 0.17–2.0, S: 0.05–0.63), but falls within the average values of calorific and ash content. The yield components of the corn leaf waste sample are described in Table 10.

Table 9. Chemical analysis of Jordan’s corn leaf waste [63].

| Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | H | N | S | O | Ash | Calorific Value | Atomic H/C Ratio |

| (wt% daf) | (wt% daf) | (wt% daf) | (wt% daf) | (wt% daf) | (wt% db) | (MJ/kg) | (-) |

| 47.7 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 42.1 ± 0.8 | 9.7 ± 0.2 | 17.9 ± 0.3 | 1.59 ± 0.07 |

Table 10. Components of Jordan’s corn leaf waste sample [63].

| Biomass Resources | Country | Productivity/Hectare | Rate/Barrel |

|---|---|---|---|

| (ton) | (USD) | ||

| Jatropha Oil | India | 3.0 | 43 |

| Palm Oil | Malaysia | 5.0 | 46 |

| Rapeseeds Oil | Europe | 1.0 | 78 |

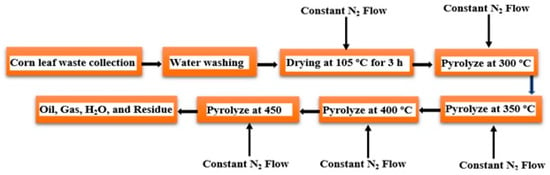

Amer et al. [63] found that the biomass feedstock of corn leaf waste could be pyrolyzed to produce biofuel using the following methodology. First, the waste should be dried at 105 °C in the presence of constant flowing N2 for 3 h. It should then be pyrolyzed in four stages at 300 °C, 350 °C, 400 °C, and 450 °C as illustrated in Figure 9. The retort should be kept at the fourth stage to ensure that no further oil is spilled. The oil product obtained from each stage should be analyzed and characterized separately. Biofuel content can then be measured as described previously, where the percentage weight of oxygen (O) content is equal to the total percentage weight of C, H, S, and N. Corn leaf waste in Jordan has a high H/C ratio, volatile matter, oxygen, and calorific value. Biomass that contains more volatile matter (more C-O) and lower ash contents generally result in greater biofuel yields. In addition, the calorific value of biofuel is less than that of conventional fossil fuels due to the high O content, low C and H contents, and relatively low C:O+H ratio compared to fossil fuels. Furthermore, the bond energy content in C-C is greater than the bond energy content in C=O and C-H. Pyrolysis at 450 °C was found to yield more oil from corn leaf waste. As the pyrolysis temperature increased, the mass flux and specific heat of the products increased while the water content decreased as moisture was removed. Corn leaf waste biofuels contain a significant amount of carbon and oxygen, which decreases as the pyrolysis temperature increases. However, it also contains a high proportion of conventional diesel (57–73%), which can be used in space heating.

Figure 9. Scheme describing the synthesis of biofuel from corn leaf waste.

3.1.2. Biodiesel from Jojoba in Jordan

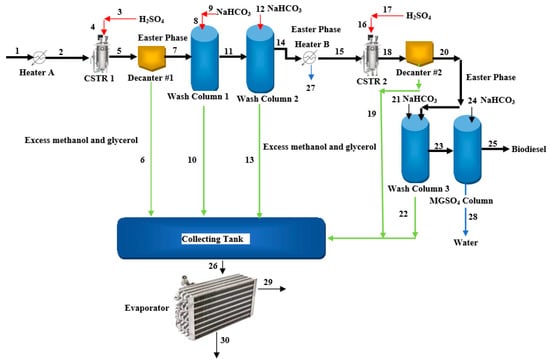

In Jordan, Jojoba is considered to be a suitable resource for biodiesel production because 40–50% of the total dry weight of its seeds is comprised of oil. Jojoba is traditionally grown in semi-arid areas, where it can acclimate to temperatures from 0 to 54 °C and <100 mm/year of rainfall. Jojoba can be grown on land that is unsuitable for most other food crops. Jojoba plants are evergreen and can survive for 150–200 years. Jojoba plants produce fruit every three years depending on the watering rate and take around 10–12 years to reach full maturity. One hectare of fully mature Jojoba plants can produce 2.0–3.5 tons of seeds and can reach production rates of around 5000 tons/ha after 12 years. Jojoba farms in eastern Badia, Jordan occupy an area of 1000 hectares with around 1666 trees/ha; each mature tree can produce 2.5 kg of seeds with an oil content of 50%, which would allow farmers to obtain nearly 1811.78 tons of oil per year. The methodology for obtaining biodiesel from Jojoba seeds is illustrated in Figure 10. This process is assumed to have an oil generation rate of 1750.62 t/h, with a capital expenditure (CAPEX) and an annual operating expenditure (OPEX) of USD 12,701.36 and USD2, 352.38, respectively. The drip irrigation framework is the most expensive part of the system and accounts for approximately 45.83% of the CAPEX and 25.79% of the OPEX. Biodiesels derived from Jojoba oils can be either used in diesel engines by combining them with conventional diesel at a specific ratio or in furnaces. Glycerol is the most common byproduct of biodiesel; this can be converted to solketal via a two-stage acetalization process. Glycerol reacted with acetone. The biodiesel cost of this project could be reported as USD 1.19/L if the glycerol byproducts are sold. However, this cost reduces to USD 0.70/L when accounting for solketal generated from glycerol byproducts [87].

Figure 10. Process flow diagram for the synthesis of biodiesel from Jojoba seed oil.

3.1.3. Biodiesel from Citrullus colocynthis in Jordan

There have been few studies on Citrullus colocynthis (Handal) as a nonedible source of biomass [159]. C. colocynthis (L.) Schrad is a vegetable plant that is usually farmed and cultivated and is geographically distributed across the deserts of Asia, the Middle East, Asia, Southern Europe, and North Africa [160]. Handal is a poisonous, crawling plant found in deserts that is closely related to watermelons and is classified as a member of the Cucurbitaceous family [159]. It can survive in hyper-arid desert environments with annual precipitation rates of 50 mm/y and an annual temperature range of 14.8–27.8 °C [161]. Handal can be grown and cultivated in sandy soils, especially during the rainy season, and produces fruit in the winter. Handal seed oil is comprised of 50 wt% of golden yellow-brown oil [162].

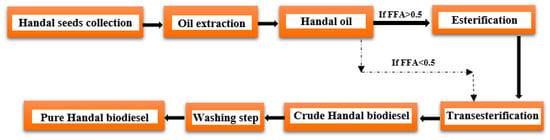

De Melo et al. [163] concluded that to determine the composition of Handal seed oil, Handal plants were gathered from various locations throughout Jordan, and the seeds from 20 kg of Handal were removed and cleaned. The seeds were dried for three days at room temperature before being ground with an electric blender. Al-Hwaiti et al. [164] found that the primary fatty acids found in Jordanian Handal seed oils were linoleic acid (74.8 ± 0.1%), palmitic acid (8.35 ± 0.03%), stearic acid (5.36 ± 0.06%), and oleic acid (9.04 ± 0.09%). Minor amounts of ω-3- and hydroxy-polyunsaturated fatty acids (<1%) were also observed. Biodiesel can be produced from Handal seed oils as described in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Process flow diagram for the synthesis of biodiesel from Handal seed oil.

3.1.4. Biodiesel from Jatropha in Jordan

Jatropha curcas is a tall bush or small tree from the Euphorbiaceae family that grows up to 5–7 m tall [166]. The origins of the Jatropha tree are unknown, but it may have originated in Mexico or Central America. It was first introduced to Africa and Asia before expanding to the rest of the world. This drought-tolerant species grows in arid and semi-arid environments, preferring well-drained soils with excellent aeration, and can adapt to peripheral soils with low nutritional value. It grows fairly quickly, starts producing seeds after 12 months, reaches peak productive capacity after five years, and can produce seeds for up to 50 years [167] is a promising, commercially viable nonedible vegetable oil. The decorticated seed of Jatropha contains 43–59% oil [168] and 30–40% [169], depending on the variety. The plant is critical for tackling climate change issues since a mature plant or tree can absorb 18 lbs of CO2 annually [170]. Becker et al. [171] found that one hectare of J. curcas can absorb up to 25 tons of atmospheric CO2 every year for around 20 years. The oil of J. curcas contains approximately 47.3% crude fat, 24.6% crude protein, and 5.54% moisture [172]. Like most other nonedible oils, J. curcas contains a high concentration of FFAs. Oils obtained from the Jatropha plant contain saturated fatty acids such as stearic acid (7.0%) and palmitic acid (14.2%), as well as unsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid (32.8%) and oleic acid (44.7%) [173].

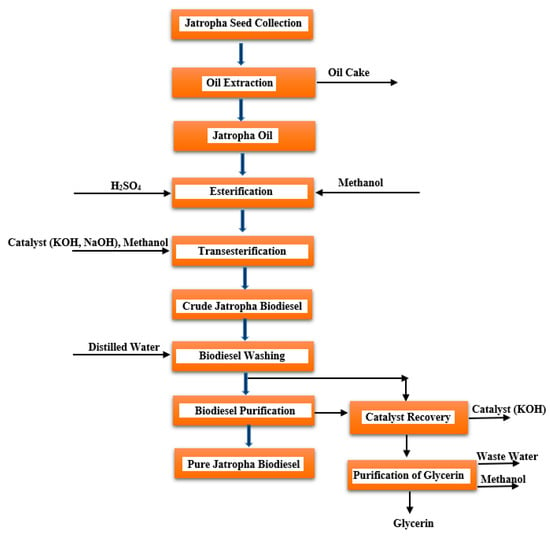

The cost of producing biodiesel is dependent on the size and type of seeds used (Table 11) [174]. Hence, Jatropha seeds appear to be a viable option for biodiesel production, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. Process flow diagram for the synthesis of biodiesel from Jatropha seed oils.

Table 11. Jatropha oil biodiesel production cost comparison with other oils [174].

| Biomass Resources | Country | Productivity/Hectare | Rate/Barrel |

|---|---|---|---|

| (ton) | (USD) | ||

| Jatropha Oil | India | 3.0 | 43 |

| Palm Oil | Malaysia | 5.0 | 46 |

| Rapeseeds Oil | Europe | 1.0 | 78 |

Recently, many researchers have investigated the pyrolysis of available vegetable oils from nonedible plants and their cakes, including J. curcas [175]. Telfah [176] concludes that Jatropha oil has a high FFA content of around 15%. Hence, a two-step pretreatment process is used to reduce the FFA content to less than 1%. The first step is a pre-esterification step conducted in methanol in the presence of a 1.0% (w/w) sulfuric acid (H2SO4) catalyst at a 0.6 (w/w) methanol to oil ratio at 50 °C for 1 h. The second step transesterifies the layer of Jatropha oil obtained using a 0.24 (w/w) methanol to oil ratio in the presence of an alkaline catalyst of 1.4% (w/w) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at 50 °C for 2 h to produce Jatropha biodiesel with a yield of around 90%. When processed using 12 wt% methanol and 1.0 wt% H2SO4 for 2 h at a temperature of 70 °C, the acid value of the obtained Jatropha oil can be diminished from 14 mg KOH/g oil to less than 1 mg KOH/g oil. The FFA content was reduced by 97% after reacting with 4 wt% solid acid and molar methanol to FFA ratio of 20:1 for 2 h at 90 °C. Phospholipids are eliminated during the pre-esterification process, eliminating the need for a separate degumming operation. A 98% biodiesel yield was generated by transesterification when using a 1.3% KOH catalyst and molar methanol to oil ratio of 6:1 at 64 °C for 20 min. Qudah et al. [174] describe another two-step process. A homogeneous acid-catalyzed pre-esterification reaction was performed at a constant temperature of 60 °C. A 100 mL round-bottomed flask was filled with 25 g of Jatropha oil and treated with concentrated H2SO4 (1.2% w/w acid to oil ratio) and dried methanol (25% w/w methanol to oil ratio); the mixture was refluxed 60 °C for 3 h. After washing the mixture to remove residual methanol and sulfuric acid, the products were dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. In the transesterification step, a KOH catalyst was used in a homogeneous base-catalyzed transesterification for 3 h at 60 °C. A 250 mL round-bottomed flask was filled with 40 g of pre-esterified Jatropha oil and heated to the appropriate temperature; the mixture was then treated with methanol (6:1 methanol to oil ratio) and KOH (1.2% w/w KOH to methanol ratio). The mixture was refluxed for 3 h while being continuously stirred. The products were then washed with distilled water and dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. This two-step process reduced the acid value of the raw Jatropha oil obtained to 0.30 mg KOH/g oil.

Qudah et al. [174] found that dolomite is a natural rock found in Jordan that contains 66% Ca, 28% Mg, and 6% Fe that can be used as a catalyst in the transesterification process. The dolomite should be crushed, finely ground, and exposed to a series of thermal treatments under flowing oxygen or ambient air before use. Two procedures that employed a dolomite catalyst were tested, and both involved treatments at 800 °C for 2 h. In the first procedure, 10 g of ground Jatropha seeds were blended with 4.0 g of dolomite catalyst, 100 mL of chloroform, and 75 mL of methanol in a 250 mL volume round-bottomed flask. The mixture was refluxed for 10 h, filtered to separate the Jatropha powder, and evaporated using a rotary evaporator to remove the solvent from the filtrate. In the second procedure, 10 g of ground Jatropha seeds were blended with nearly 100 mL chloroform in a 250 mL round-bottomed flask. After filtration, the liquid phase was transferred into a 250 mL flask and blended with 4.0 g of dolomite catalyst and 75 mL of methanol. The mixture was constantly agitated for 2 h at 60 °C and subsequently refluxed for 10 h before being evaporated with a rotary evaporator to remove the solvent under reduced pressure. To optimize the transesterification process (>96% conversion rate) of Jatropha seed oils at 60 °C and 6:1 methanol to oil ratios, the dolomite should be thermally activated at 800 °C for at least 30 min. This heightened activity is correlated with the creation of CaO but not MgO, which forms when heated to 600 °C. The minimum mass ratio of catalyst to oil required to achieve such an ideal biodiesel yield is 1:50 (2%); It is important to note that the catalyst cannot be recycled and can only accomplish a 2% transesterification rate if reused. Nevertheless, activated dolomite can be considered to be a less expensive alternative to the more commonly used KOH catalyst.

The viscosity of J. curcas oil/diesel fuel blends at ratios of 50:50 and 40:60 is similar to that of pure diesel fuel at the temperature of 328–333 K and ~318 K, respectively, while a mixture of J. curcas oil/diesel fuel at a ratio of 30:70 has a viscosity similar to diesel fuel at the temperature of 308–313 K [177].

3.2. Potential Yield of Biogases in Jordan

Figure 13 shows that biogas technology has grown in popularity over the last few decades [178]. Biogas can be used as a replacement for natural gas (NG) in stoves. It can also be used to produce electricity by feeding an internal combustion engine that is directly connected to an electrical generator. The extra heat from the combustion engine can heat an entire room (space heating) as well as heat the anaerobic digester [36]. However, these applications have not yet been widely adopted in developing countries [178]. Al-hamamre et al. [31] concluded that Jordan is theoretically capable of producing approximately 706.9 MCM of biogas per year even without taking the availability of energy into account; this is equivalent to around 388.1 MCM of NG per year or 2.57 MCM of barrel oil per year. Al-hamamre et al. [37] reported that the total amount of biogas that Jordan could theoretically generate is around 428.19 MCM/year and that it can also generate around 235.5 MCM of methane (CH4) per year. This amount would account for 29.2% of Egypt’s total NG imports in 2011 (Table 12). Al-hamamre et al. [36] also found that if Jordanian biogas was used for electricity generation, this would generate approximately 917.41 GWhe of power per year, which would be 17% more than the total amount of power imported from Syria and Egypt (784.3 GWhe), assuming a conversion efficiency (biogas to electricity) of 27.5%.

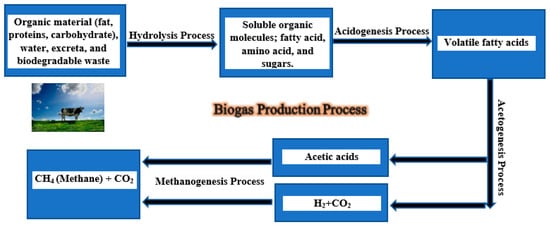

Figure 13. Scheme describing the production of biogas.

Table 12. Jordan’s biogas and electricity yield potential [37].

| Biomass Resources | BG Yield * | Electricity |

|---|---|---|

| TJ/year | GWhe/year | |

| Animal Manure | 600.5 | 45.9 |

| Agricultural Residue | 644.5 | 49.2 |

| Sludge and Wastes | 1224.2 | 93.5 |

| Total | 2469.2 | 188.6 |

* BG Yield: considering availability energy factor of 12.5.

As a sustainable source of energy, biogas can play a key role in maintaining the balance between long-term advancement, economic strength, and the preservation of the environment in Asia [179]. Recently, the anaerobic digestion of agricultural and industrial waste has emerged as one of the most appealing sustainable energy solutions. The most popular digester designs are fixed domes (Chinese type) and floating covers (Indian type) [178]. However, Surendra et al. [180] found that these two types of digests are difficult to adopt in developing countries; they do not provide temperature control, have prohibitively expensive installation costs for farmers, and require specialized skills. The biogas produced from biological waste is mostly a natural process. Hence, a majority of the project’s costs involve the collection of waste and the construction of the biogas plant [158]. Al-hamamre et al. [37] found that the total annual power that Jordan might theoretically generate from CH4 was around 698.1 GWhe, which is equivalent to around 5.09% of energy consumption in 2011 and 39.65% of the power imported from Egypt and Syria. Abu Qdais et al. [181] also calculated that if all potential biomass in Jordan was used to generate energy in 2012, about 53.35% of the primary energy consumption could be replaced by NG or could replace about 66.23% of the total amount of NG imported from Egypt. They found that 28.34% of this biogas could be generated from animal waste and that 62.18% of this amount could be derived from sheep and goat waste, with poultry residues contributing the remaining 32.29%. Biogas production from dung could be used as a substitute for conventional fossil fuels in the generation of electricity and would thus contribute to the reduction of GHG emissions and other pollutants [178]. Al-hamamre et al. [36] found that the use of anaerobic digestion to produce biogas would be an alternative to traditional waste disposal methods in Jordan (such as landfilling or incineration), which emits toxic gases such as CO2 and carbon monoxide (CO). Jafar and Awad [178] reported that the most common applications for biogas were limited to lighting and cooking in developing countries. Utilizing biogas in rural areas would cut down on firewood consumption, prevent deforestation, and boost soil productivity; hence, biogas could contribute significantly to sustainable development. Milbrandt and Overend [182] concluded that the amount of biogas produced is primarily dependent on the digester volume. The main components of biogas are CH4 (50–70%) and CO2 (30–50%), with the rest being trace gases (hydrogen and nitrogen) [36]. Wang Ris [183] found that a pretreatment process was necessary to enhance CH4 production via anaerobic digestion. Al-hamamre et al. [36] concluded that when co-digesting agricultural waste with cattle manure, the yield of biogas products increased by 0.62 L/kg volatile solid (VS). About 85.62 GWhe of electricity could be obtained if the MSW in the Akaider landfill was used, saving approximately 92.86–194.8 × 103 t/year of CO2. Furthermore, nearly 538.2 GWhe of electricity can be obtained by using the MSW in the Al-Ghabawi landfill with CO2-equivalent savings of 582–1220 × 103 t/year. Each ton of MSW used to produce electricity can reduce CO2 emissions by around 725–1520 kg. If the entire supply of MSW was used to obtain electricity, this number could reach 1005 × 103–2108 × 103 kg. Malkawi et al. [158] found that in the absence of “fuel costs”, operational expenses tended to be less than that of traditional power plants. However, due to socioeconomic and institutional barriers, the prospective growth of the Asian biogas industry is relatively poor [179]. Aggarangsi et al. [184] found that biogas digesters significantly decrease environmental pollution.

A summary of Jordanian bioenergy research and how it compares to global bioenergy technology is presented in Table 13 and Table 14.

Table 13. Summary of Jordan’s bioenergy.

| Biomass Resources | Bioenergy | Process | Applicability | Conclusion | Findings | Strength | Shortcoming |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn leaf waste | Biofuel | Pyrolyss (300–450 °C) |

Applicable | Feasible | 450 °C was found to yield more oil from corn leaf waste. | Chemical analysis is well considered. | Economic analysis is not considered Nanotechnologies are not considered. |

| Jojoba oil | Biodiesel | Esterification and transesterification | Applicable | Feasible (CAPEX USD 12,701.36, OPEX USD 2352.38) |

|

Economic analysis is considered. |

|

| Citrullus Colocynts (Handal) seeds oil | Biodiesel | Esterification and transesterification | Applicable | Feasible |

|

|

|

| Jatropha | Biodiesel | Esterification and transesterification | Applicable | Feasible |

|

|

|

| MSW and animal manure | Biogas | Anaerobic digestion | Applicable | Feasible |

|

Different biomass resources are considered (MSW, animal manure) with suitable technical and economic analysis. |

|

Table 14. Jordan’s bioenergy in comparisons with global bioenergy.

| Biomass Resources | Country | Bioenergy | Process | LCC | Techno-Economy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn leaf waste | Jordan [63] | Biofuel | Pyrolysis (300–450 °C). | - | 450 °C was found to yield more oil from corn leaf waste. |

| Cornleaf-waste | Canada [185] | Biofuel | Pyrolysis (200–430 °C). | - | At 550 °C, a biochar yield of 10% to 12% is achievable. |

| Jojoba oil | Jordan [87] | Biodiesel | Esterification: It is used in the production line of biodiesel to reduce the fatty acid concentration to less than 1.0 wt% before getting a transesterification reaction. Transesterification: Using KOH 1.0 w/w as a catalyst. Methanol to oil ratio (1:3.3). The reaction temperature is 65 °C. |

CAPEX USD 12,701.36. OPEX USD 2352.38. |

The biodiesel cost reduces to USD 0.70/L when accounting for solketal generated from glycerol byproducts. |

| Jojoba oil | Egypt [186] | Biodiesel | Transesterification: Using KOH 0.5 wt% as a catalyst. Methanol to oil ratio (3:18:1) by step 1:1. Reaction time (0.5 h to 3.0 h) by step 0.5 h. | - |

|

| Jojoba oil | India [187] | Biodiesel | Transesterification: No catalyst. Methanol to oil ratio (30:1). The reaction temperature is 278 °C. The reaction pressure is 123 bars. Reaction time 23 min. | - | At optimal conditions, the supercritical methanol transesterification method creates the most biodiesel (95.67%). |

| Citrullus Colocynths (Handal) seeds oil | Jordan [165] | Biodiesel | Esterification: The catalyst is sulfuric acid (H2SO4), and the reactant is methanol (CH3OH). The FFA content after esterification must be less than 0.5% for biodiesel production. Transesterification: The optimal method for the transesterification of Handal oil requires the addition of methanol equivalent to 0.217 × (unreacted triglycerides in grams) as well as sodium methoxide equal to [0.25 + 0.19 × (%FFA)]/[100 × unreacted triglycerides in grams]. The crude biodiesel obtained is then washed and purified with hot water. |

- |

|

| Jatropha seeds oil | Jordan [176] | Biodiesel | Esterification: Using methanol in the presence of a 1.0% (w/w) sulfuric acid (H2SO4) catalyst at a 0.6 (w/w) methanol to oil ratio at 50 °C for 1 h Transesterification: using a 0.24 (w/w) methanol to oil ratio in the presence of an alkaline catalyst of 1.4% (w/w) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at 50 °C for 2 h to produce Jatropha biodiesel with a yield of around 90%. |

USD 43 per barrel | A 98% biodiesel yield was generated by transesterification when using a 1.3% KOH catalyst and molar methanol to oil ratio of 6:1 at 64 °C for 20 min. |

| Jatropha seeds oil | Jordan [174] | Biodiesel | Esterification and transesterification using KOH as a catalyst. Esterification and transesterification using dolomite as a catalyst. |

- | Activated dolomite can be considered to be a less expensive alternative to the more commonly used KOH catalyst. |

| Jatropha seeds oil | India [188] | Biodiesel | In the transesterification reactor, Jatropha seeds oil is combined with alcohol (Methanol) and a catalyst mixture (KOH, NaOH). The reactor is maintained at reaction temperature for a set period of time while being vigorously agitated. Following the reaction, the biodiesel and glycerol mixture is transferred to the glycerol sedimentation tanks. Crude Jatropha biodiesel is gathered and washed with water to obtain pure biodiesel. | - |

|

| Jatropha seeds oil | Egypt [189] | Biodiesel | Transesterification: Using NaOH 1.0 wt% as a catalyst. Methanol to oil ratio (6:1). Reaction time 1.0 h. Reaction Temperature 338 K. Yield 93.0%. |

- |

|

| Jatropha seeds oil | India [190] | Biodiesel | Esterification: It is conducted in the presence of a sulfuric acid catalyst (H2SO4) and NaOH. Transesterification: Using KOH 0.55 wt% as a catalyst. Methanol to oil ratio (5.41:1). Reaction time 1.0 h. Reaction Temperature 333 K. Yield 93.0%. |

- | The maximum biodiesel yield with two steps of esterification and transesterification was 93% (v/v), which was higher than that with one-step (transesterification) at 80.5%. |

| MSW, animal manure | Jordan [36,37,181,191] | Biogas | Anaerobic digestion (Landfill) |

Feasible | 1. The total amount of biogas that could potentially be created is around 817 MCM/year. 2. Total amount of power that might be theoretically acquired from CH4 yield per year is 961 GWhe. |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pr11040992

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!