Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Since the dawn of Brazilian trade, extensive cattle farming has predominated. Brazil’s extensive pasture-based system uses pasture plants adapted to climate and soil conditions with limited use of purchased inputs. Domestic and international stakeholders have prioritized sustainable agricultural development in Brazil’s beef sector to reduce deforestation and other natural-habitat conversions.

- Amazon

- beef

- Brazil

- deforestation

- environmental impacts

1. Introduction: History of Cattle Breeding and Production Systems in Brazil

The growth of beef cattle in Brazil has solidified the country in international markets as one of the largest exporters of beef. In 2021, the Brazilian herd was estimated at 196.47 million head, with 39.14 million head slaughtered. The volume of meat produced was 9.71 million metric tons of carcass-equivalent weight. Of this total volume, 25.51% of Brazil’s beef production—2.48 million metric tons—was exported, while 7.24 million metric tons—equivalent to 74.49% of Brazil’s beef production—were destined for the domestic market [1]. Brazil’s beef production has historically and currently been dominated by an extensive pasture-based system, in which animals typically take two to four years to reach slaughter weight [2].

Brazilian cattle are predominantly tropic breeds (Bos indicus, such as the Nelore breed), with temperate breeds (Bos taurus) more prevalent in southern Brazil. During their evolution, Bos indicus cattle acquired genes that confer a greater thermotolerance in response to heat stress than that of European breeds. This is one of several reasons that Bos indicus (e.g., Nelore) are the predominant cattle in central Brazil, which has high temperatures and a dry climate throughout the year [3]. Bos taurus cattle are generally more adapted to environments with milder and more humid temperatures, such as those as found in the southern region of Brazil [4]. Cattle gain weight during the wet season (October through March) but lose weight during the dry season (April through September) as pasture productivity diminishes (Figure 1). Brazil’s pastures comprise approximately 151 million hectares, including areas that are both natural and cultivated (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Beef cattle (Bos indicus, such as the Nelore breed) grazing on extensive pasture (Brachiaria spp.) during the (a) wet season and (b) dry season in midwest region of Brazil (Source: corresponding author).

Figure 2. Spatial distribution of pasture areas in Brazil in states and the federal district in 2021.

However, Brazil’s current beef production, trade, and marketing are completely different from those practices in Brazil’s beef industry 40 years ago. Then, the total beef herd was less than half of the current total, and beef production did not completely meet the Brazilian population’s consumer demand [5]. In 2021, the beef production of 9.71 million metric tons of carcass-equivalent weight [1] was enough to meet the domestic demand for beef, which was 36.4 kg per person per year [6]. Even with more recent increases in beef production, the total pasture area associated with beef cattle has declined due to intensification strategies used in Brazil’s beef production systems (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Total Brazilian cattle herds and pasture areas from 1985 to 2021.

The first cattle arrived in Brazil in 1533, during the establishment of the first Portuguese colony on the island of São Vicente in the state of São Paulo [7]. In the middle of the 16th century, the Portuguese royal court encouraged the export of cattle to the Bahian Recôncavo region in northeastern Brazil. Gradually, with the growth of the economy in coastal areas, cattle raising expanded into the country’s interior [8]. Since these commercial beginnings, Brazil’s beef production has relied on an extensive pasture-based system, using plants adapted to local climate and soil conditions, with limited use of inputs [9].

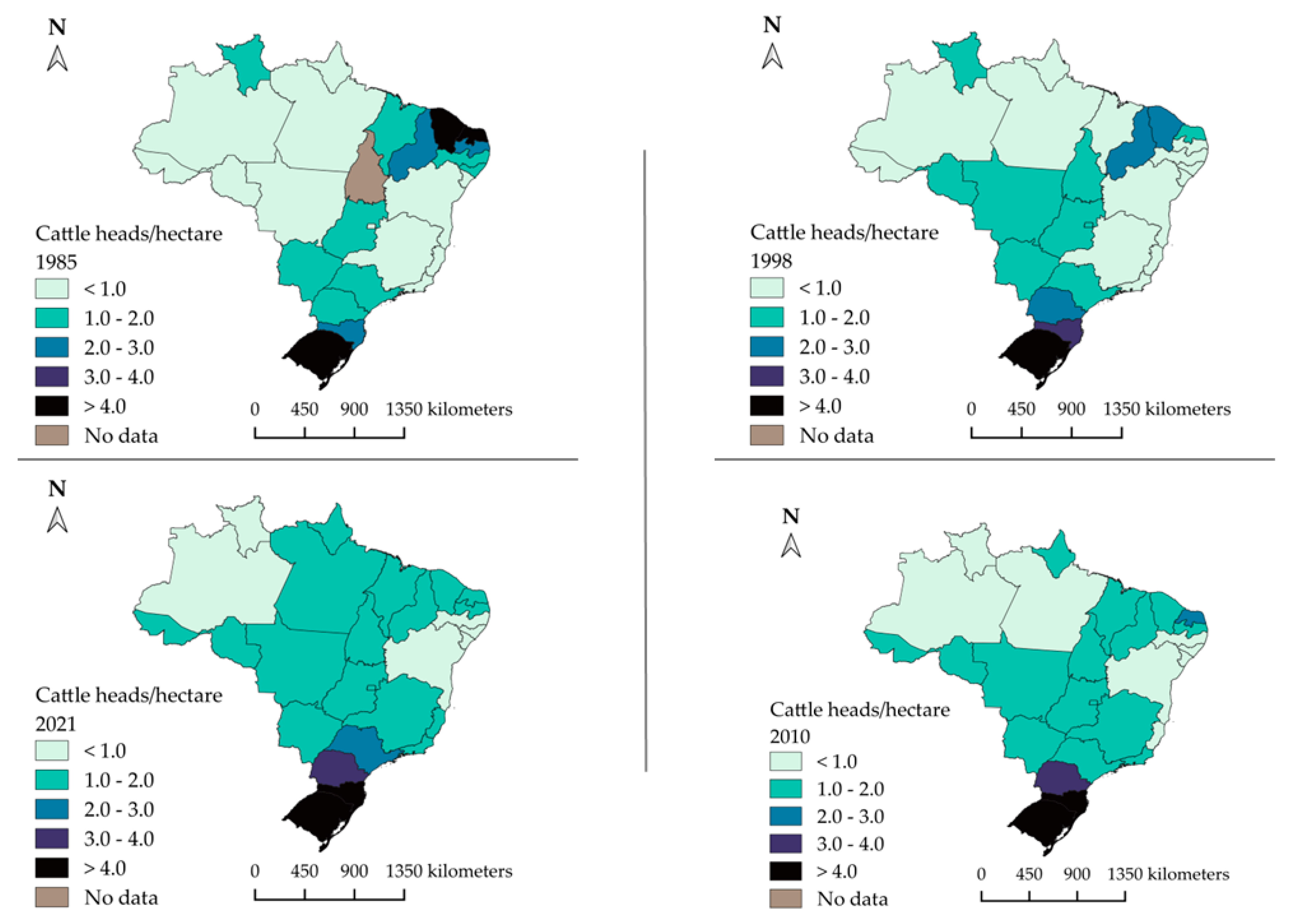

With the opening of the Brazilian economy and the greater financial support of the agricultural sector in the 1990s, profound changes in Brazil’s beef industry took place thereafter [10]. The development of practices aimed at increasing productivity has led to increases in intensive production systems in some regions. These technologies involve the genetic improvement of the animals, control of the economic management of the property, and a supply of concentrated feed for the animals, using feedlots or semi-feedlots to reduce the time to slaughter and increase profitability [11]. Thus, there has been a recent increase in cattle herd size (Figure 4), together with increases in cattle stocking density (head/hectare) (Figure 5), in particular regions in Brazil. Regions with such increases include the northern and central parts of Brazil, such as Brazil’s center-west and north regions. While cattle herd numbers have stayed relatively stable from 1985 to 2021 in Brazil’s northeastern, southeastern, and southern regions, the numbers have expanded in the north (from 5.3 to 55.7 million) and center-west (from 41.1 to 75.4 million) over these 36 years (Figure 4). Stocking densities of cattle are relatively high (>1 head/hectare), except for states along Brazil’s southeastern coast. The adoption of the new technologies that allow for increased productivity and profitability in the beef cattle industry was possible due to the support and public policies developed for agricultural production in Brazil, with a focus on these developments occurring in a sustainable way [12].

Figure 4. Cattle herd sizes (heads) in the northern, northeastern, southeastern, southern, and center-west regions of Brazil in the years 1985, 1998, 2010, and 2021.

Figure 5. Cattle stocking densities (heads/hectares) by Brazilian states in 1985, 1998, 2010, and 2021.

Such incentives have occurred because extensive systems have low efficiency, as they are based on cattle production with low technological intensity and management standards [11]. Thus, extensive systems for producing Brazilian beef have low productivity, requiring large amounts of land for grazing on seeded pastures that, over time, can become over-grazed and degraded [13]. Amazon rainforest deforestation, which precedes the establishment of pastures, has focused international attention on reducing deforestation [6]. This attention has encouraged three types of intensification in Brazil’s beef-production systems to produce more beef on already existing pastureland: (1) re-seeding degraded pastures, (2) feeding grains in pastures, and (3) semi-intensive feedlots [14]. Pasture re-seeding involves the new establishment of pastures through forage sowing and fertilization to meet the plant requirements that are needed to optimize production [14]. Beef cattle can be fed grain at feeding stations in pastures that typically have low nutritional value [15]. Feedlots typically supply concentrated feeds for finishing animals, where the feeds normally consist of an energy and protein source [16]. Management-intensive rotational grazing—where cattle are rotated daily between paddocks that have been created by portable, electrified poly-wire—is much less popular [17], reinforcing producers’ preferences for management systems that take less time.

2. Recent Public Policies for More Sustainable Livestock in Brazil

2.1. Agricultural Policies Directly Supporting Sustainable Livestock

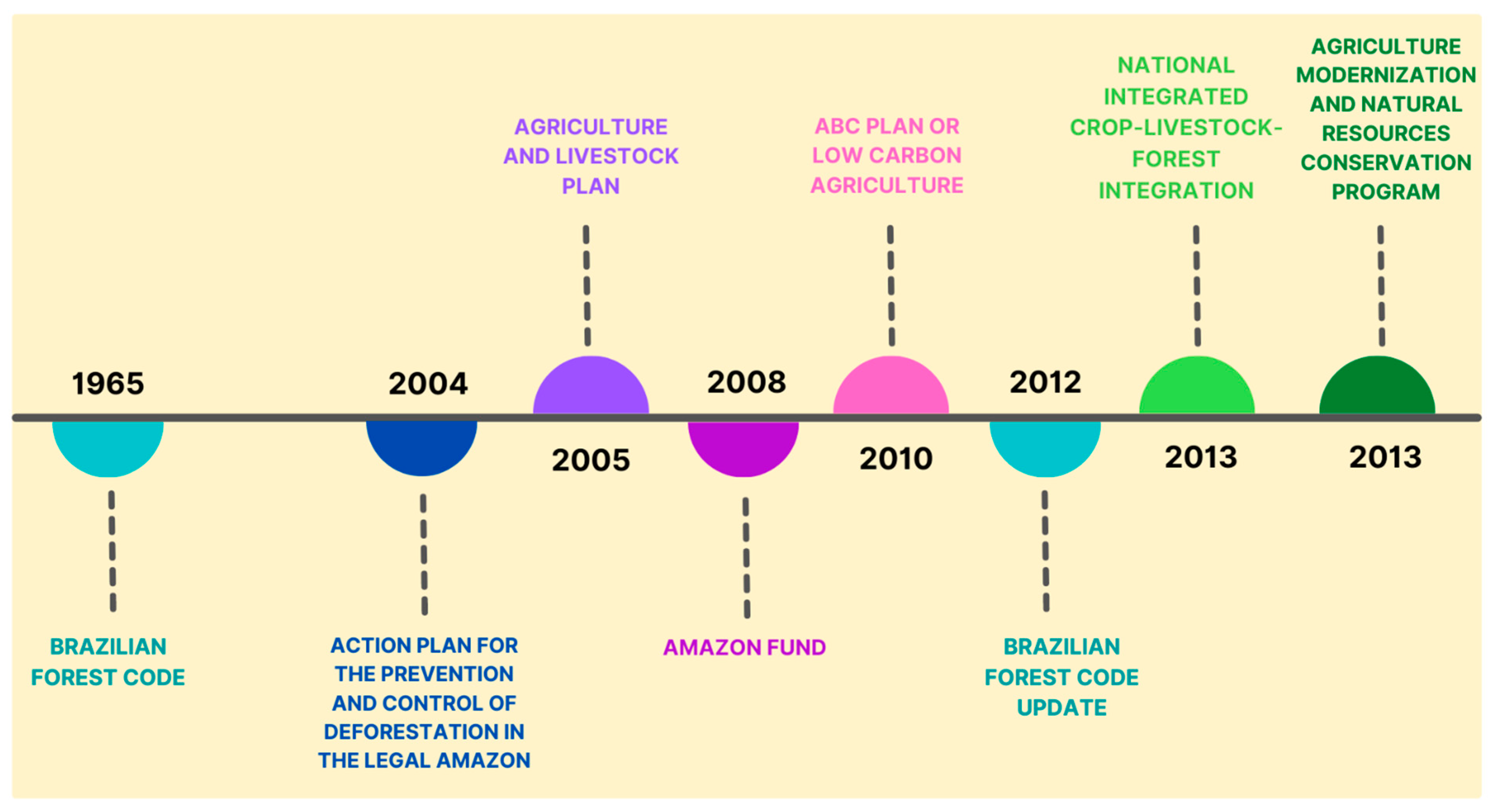

Researchers ordered recently enacted public policies in Brazil from the least challenging to the most challenging for producers to adopt. Most of these policies, with the exception of the 1965 Brazilian Forest Code, have been adopted over the past two decades. It is important to note how involved beef producers have been with these programs and to what extent these policies encourage sustainable intensification strategies for Brazil beef production. These strategies include good agricultural practices, low-carbon production, integrated crop–livestock–forest systems, pasture-based grain supplementation, pasture rehabilitation, and semi-intensive feedlots.

2.1.1. Agriculture and Livestock Plan (Plano Agrícola e Pecuário)

Brazil’s Agriculture and Livestock Plan is the main instrument for directing public policies aimed at the agricultural sector. The plan includes measures to encourage the production of certain products, while providing resources for agricultural producers, including credit at favorable interest rates that is made available throughout the harvest year. Brazil’s harvest year runs from July to June. The amount of money devoted to the Agriculture and Livestock Plan depends on the budget of the National Treasury and the amount allocated to financial subsidies for the agricultural sector [18].

The Agriculture and Livestock Plan embodies the main measures to support commercialization, rural risk management, and credit support. Thus, government actions are necessary to ensure the continuity of the advances that have been already achieved in increasing agricultural productivity. The Agriculture and Livestock Plan also can sustain the income of rural producers and ensure the flow of food, fuel, and fiber to both domestic and international markets. Brazil has had favorable conditions related to production costs, which have increased the competitiveness of its agricultural exports [19].

The annual publication of the previous Crop Plan became a tradition, dealing only with questions related to crops and marginalizing the livestock sector. In 2000, thanks to requests from entities representing milk producers and their cooperatives and to the sensitivity of the Brazilian government, the famous Crop Plan proposed measures related to dairy production for the first time. In the same year, the previous Crop Plan was renamed the Agriculture and Livestock Plan to definitively address livestock via announced measures [20].

The Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), which is considered to be an important developer of technologies in the Brazilian agricultural sector, is mentioned in the Agriculture and Livestock Plan 2012–2013. Among the highlights of Embrapa’s programs is the Good Agricultural Practices Program (GAPP) for beef cattle. The GAPP is not an agricultural credit measure, but rather a mechanism within the plans that can differentiate access to credit by rural producers. Created in 2005, this program encompasses a set of norms and procedures that must be observed by rural producers in order to make their properties more sustainable. Various factors, such as the management and the social function of rural properties, human resources management, environmental management, rural facilities, pre-slaughter management, animal welfare, pastures, food supplementation, animal identification, sanitary control, and reproductive management, are crucial for the effectiveness of GAPP’s adoption on farms [21].

2.1.2. ABC Plan, or Low-Carbon Agriculture Plan (Agricultura de Baixa Emissão de Carbono)

The Sectorial Plan for Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change for the Consolidation of a Low-Carbon Economy in Agriculture, also known as the ABC plan, is one of the sectoral plans prepared in accordance with Article 3 of Decree No. 7.390/2010. Its purpose is to organize and plan actions to be carried out for the adoption of sustainable production technologies. These sustainable technologies are selected with the objective of responding to Brazil’s commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the agricultural sector [22]. The ABC plan addresses climate change, ecosystem and biodiversity management, resource use efficiency, and sustainable consumption/production, in addition to presenting guidelines for environmental governance, thereby contributing to the exchange of information and experiences among the public, private, and academic sectors [23].

The ABC plan is composed of seven programs, six of which refer to mitigation technologies, and another that includes actions needed to adapt to climate change. The first program involves rehabilitating degraded pastures. The second program is the integration of crop–livestock–forest (ICLF) systems and agroforestry systems (AFSs), which involves integrating commercial forestry species (e.g., Eucalyptus sp.) with commodity crops, such as soybeans (Glycine max L.), corn (Zea mays L.), and cotton (Gossypium sp.), and livestock, such as beef (Bos indicus, such as Nelore cattle). The third and fourth programs comprise the direct planting system (DPS) and biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) programs, which involve soil mobilization only in a sowing line or planting hole, the permanent maintenance of soil cover, species diversification, and increased fertilization efficiency. The fifth program involves re-forestation, while the sixth program focuses on the treatment of animal waste. Finally, the seventh program addresses climate-change adaptation [24].

The ABC program provides agricultural producers with opportunities to incorporate sustainable technologies into their production processes for more efficient production. This can increase income through increased productivity and product diversification. It also can mitigate environmental liabilities, reduce pressure on native forests, and lower GHG emissions, thereby enhancing sustainable agricultural production of food for local Brazilian and export markets. This new sustainable agricultural program involves government incentives that provide attractive alternatives to existing financing instruments in the marketplace [25]. With the adoption of more sustainable techniques and production systems, it is possible to increase productivity, reduce deforestation, reconcile soil and water conservation, adapt rural properties to environmental legislation, expand the area of cultivated forests, and encourage the recovery of degraded areas [26].

2.1.3. National Integrated Crop–Livestock–Forest Policy (Política Nacional de ICLF)

The silvopastoral system is a technological option for integrated crop–livestock–forest integration that consists of an intentional combination of trees, pastures, and cattle in the same area at the same time. The approval of Law 708/07 on 4 February 2013 established the National Integrated Crop–Livestock–Forest Integration (ICLF) policy in Brazil. The ICLF policy reinforces the growing interest in the use of sustainable production systems. This law integrates agricultural and forestry activities carried out in the same area, in consortium, in succession, or in rotation. It seeks synergistic effects between the components of the agroecosystem, with objectives of recovering degraded areas, and enhancing economic viability, and supporting environmental sustainability [27].

The ICLF policy is a production strategy that includes the economic, social, and environmental aspects of sustainability. With the growing concern about the relationship between the environment and livestock, the challenge of establishing sustainable production systems is paramount. Silvopastoral systems are capable of meeting this challenge [28].

The ICLF policy’s core principles involve the preservation and improvement of the soil’s physical, chemical, and biological conditions and compliance with environmental protection laws. Cooperation between the public and private sectors and non-governmental organizations is recommended to foster the diversification of economic activities. Another policy guideline is the encouragement of direct planting in crop residue from the preceding crop as a soil-conservation management practice [29]. The ICLF policy also aims to mitigate deforestation caused by land-use conversion of native vegetation into pastures and/or crops and contributes to the maintenance of permanent preservation areas and legal reserves. The recovery of degraded pasture areas is also encouraged via sustainable production systems, such as the adoption of conservation practices and agricultural systems that maintain higher levels of organic matter in the soil and that reduce greenhouse gas emissions [30].

2.1.4. Agriculture Modernization and Natural Resources Conservation Program (Programa de Modernização da Agricultura e Conservação de Recursos Naturais—Moderagro)

The Moderagro (the Program for the Modernization of Agriculture and Conservation of Natural Resources) aims to support and encourage the production, processing, industrialization, packaging, and storage of agricultural products. This program is a Banco Nacional do Desenvolvimento (BNDES) project that enables rural producers to finance actions to recover soils, defend animals, acquire and apply agricultural fertilizers, and build facilities for the storage of agricultural machinery and implements, as well as for the storage of inputs [31]. The program supports and encourages the sectors of production, processing, industrialization, packaging, and storage of animal products from the beekeeping, aquaculture, poultry, chinchilla, rabbit, sheep and goat, frog, pig, and dairy farming industries. The agricultural production of floriculture, fruits, olives, horticulture, palm trees, yerba mate, nuts, and fishing are also encouraged [32].

2.2. Agricultural Policies Indirectly Supporting Sustainable Livestock

Other recently enacted environmental policies in Brazil have had more of an indirect impact of improving the sustainability of Brazil’s livestock. These public policies have reduced Amazon deforestation and Cerrado habitat conversion. In general, these public policies were enacted earlier than policies that directly focus on livestock (Figure 6). Researchers discuss whether beef producers were engaged and involved in the writing and implementation of these public policies. They also highlight how influential the limitation of grazing areas for cattle by preserving native habitat has been in encouraging beef producers to sustainably intensify their production systems.

Figure 6. Historical timeline of direct and indirect public policies impacting sustainability in Brazil’s beef cattle industry from 1965 to 2013.

2.2.1. The 1965 Brazilian Forest Code & 2012 Update (1965 & 2012 Código Florestal Brasileiro)

The Brazilian Forest Code is an indispensable political instrument for managing the country’s economic development. Focusing on the different historical periods in Brazil, the evolution of the Brazilian Forest Code (BFC) reflects past political, economic, and environmental events, as well as the development intentions articulated through the law [33]. The BFC was created in 1965 with the aim of preserving forests and streamlining their management. At the time the code was created, the main agricultural activities were coffee (Coffea arabica and Coffea robusta) and sugar cane (Saccharum spp.). The code also contained several provisions, such as the prohibition of occupying steep slopes and a determination for rural landowners to maintain a reserve of native vegetation on their farms to contribute to preserving existing forests [34].

Although instituted in 1965, it was only in the 1980s that the Legal Reserve and Permanent Preservation Areas were effectively introduced into law, via a provisional measure. Another important aspect of the 1965 code was the creation of the National System of Conservation Units, which covered the different types and categories of protected areas within a single management system [35]. Law 12,651, which dates from 25 May 2012, introduced a series of new forest regulations. The 2012 Forest Code, currently on the books, consolidated protected areas from the previous code and included conceptualizations/specifications for delimitation of each area provided for in the law [33].

The BFC laws’ innovations resulted in the creation of the Rural Environmental Registry (RER), as well as implementation of the Environmental Regularization Program. Under the RER, it is possible for the federal government and state environmental agencies to determine the location of each rural property and the status of its adherence to environmental standards for the preservation of native vegetation on the property. Additionally, the new law authorizes a series of benefits for family farmers or owners of smaller properties by including their properties in the RER [36].

The RER is a nationwide electronic registration system for gathering data on rural properties/possessions that are used for environmental and economic planning and for combating deforestation. The RER is the first step enabling rural producers to show that their rural property complies with the Forestry Code. If an owner does not register in the system, the owner is prevented from having access to agricultural credit from financial institutions. In addition, it can be difficult for rural producers to sell their agricultural products, as some companies require RER documentation from producers in order to buy their products [37].

2.2.2. Plan to Prevent and Control Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon

The Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (APCDAm) was created in 2004 with the aim of continuously reducing deforestation and creating conditions for the transition to a sustainable development model in the Legal Amazon. One of the main initial challenges was to integrate the fight against deforestation into Brazilian State policies [19]. Thus, the APCDAm became a strategic initiative of the Brazilian government that was included in the guidelines and priorities of this sustainable development plan for the Amazon. Therefore, the problem of the Amazon became part of the political agendas at the highest levels of the federal government and ministries [38].

Because the fight against the causes of deforestation could no longer be conducted in isolation by environmental agencies, the complexity of the challenge required coordinated efforts from different sectors of the federal government [19]. The APCDAm is implemented by more than a dozen government ministries; it was coordinated by the Civil House until March 2013, and thereafter by the Ministry of the Environment. The APCDAm is structured to address the causes of deforestation in a comprehensive, integrated, and intensive way, with actions articulated around three themes: land and territorial organization, environmental monitoring and control, and the promotion of sustainable production [39].

2.2.3. Amazon Fund (Fundo Amazon)

The Amazon Fund aims to encourage Brazil and other developing countries that have tropical forests to maintain and increase voluntary reductions in the emission of greenhouse gases caused by deforestation and land degradation [40]. The Amazon Fund was created by Decree No. 6527 on 1 August 2008. This fund raises donations for non-reimbursable investments to prevent, monitor, and combat deforestation and to promote the conservation and sustainable use of forests in the Amazon biome. Its creation was a consequence of the success achieved by the APCDAm in reducing deforestation in the Amazon since its implementation in 2004. The creation and raising of resources by the Amazon Fund have led to funding Brazilian efforts to reduce the loss of forests via projects that work on this theme, in synergy with government agencies [39].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su15064801

References

- Abiec Associação Brasileira das Indústrias Exportadoras de Carnes. Beef Report. Perfil da Pecuária No Brasil, Disponíve. 2022. Available online: https://www.abiec.com.br/publicacoes/beef-report-2022/ (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Ferraz, J.B.S.; de Felício, P.E. Production systems-An example from Brazil. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 238–243.

- Hansen, P.J. Physiological and cellular adaptations of zebu cattle to thermal stress. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2004, 82–83, 349–360.

- Utsunomiya, Y.T.; Fortunato, A.A.A.D.; Milanesi, M.; Trigo, B.B.; Alves, N.F.; Sonstegard, T.S.; Garcia, J.F. Bos taurus haplotypes segregating in Nellore (Bos Indicus) cattle. Anim. Genet. 2021, 53, 58–67.

- Vale, R.; Vale, P.; Gibbs, H.; Pedrón, D.; Engelmann, J.; Pereira, R.; Barreto, P. Regional expansion of the beef industry in Brazil: From the coast to the Amazon, 1966–2017. Regional Studies. Reg. Sci. 2002, 9, 641–664.

- Magalhaes, D.R.; Maza, M.T.; Prado, I.N.D.; Fiorentini, G.; Kirinus, J.K.; Campo, M.D.M. An Exploratory Study of the Purchase and Consumption of Beef: Geographical and Cultural Differences between Spain and Brazil. Foods 2022, 11, 129.

- Amaral, G.; Carvalho, F.; Capanema, L.; Carvalho, C.A. Panorama da Pecuária Sustentável. BNDES Setorial 36. 2012; pp. 249–288. Available online: https://web.bndes.gov.br/bib/jspui/handle/1408/1491 (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Miranda, R.A. Breve história da agropecuária brasileira. In Dinâmica da Produção Agropecuária e da Paisagem Natural No Brazil Nas Últimas Décadas: Sistemas Agrícolas, Paisagem Natural e Análise Integrada Do Espaço Rural; Landau, E.C., Silva, G.A.D., Moura, L., Hirsch, A., Guimaraes, D.P., Eds.; Cenário Histórico, Divisão Política, Características Demográficas, Socioeconômicas e Ambientais; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2020; pp. 31–57.

- Silva, M.C.; Boaventura, V.M.; Fioravanti, M.C.S.; História do Povoamento Bovino No Brasil Central. Revista UFG. Ano XIII nº 13. 2012. Available online: https://revistas.ufg.br/revistaufg/article/view/48451 (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Romanzini, E.P.; Barbero, R.P.; Reis, R.A.; Hadley, D.; Malheiros, E.B. Economic evaluation from beef cattle production industry with intensification in Brazil’s tropical pastures. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 2659–2666.

- Daniel, J.L.; Bernardes, T.F.; Jobim, C.C.; Schmidt, P.; Nussio, L.G. Production and utilization of silages in tropical areas with focus on Brazil. Grass Forage Sci. 2019, 74, 188–200.

- Lamas, F.M. Artigo: A Tecnologia Na Agricultura; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/30015917/artigo-a-tecnologia-na-agricultura (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Figueiredo, E.B.; Jayasundara, S.; Bordonal, R.O.; Berchielli, T.T.; Reis, R.A.; Wagner-Riddle, C.; La Scala, N. Greenhouse gas balance and carbon footprint of beef cattle in three contrasting pasture-management systems in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 420–431.

- Vale, P.; Gibbs, H.; Vale, R.; Christie, M.; Florence, E.; Munger, J.; Sabaini, D. The Expansion of Intensive Beef Farming to the Brazilian Amazon. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 57, 101922.

- Molossi, L.; Hoshide, A.K.; Pedrosa, L.M.; Oliveira, A.S.D.; Abreu, D.C. Improve pasture or feed grain? Greenhouse gas emissions, profitability, and resource use for Nelore beef cattle in Brazil’s Cerrado and Amazon biomes. Animals 2020, 10, 1386.

- Da Rosa e Silva, P.I.J.L.; Vilas Boas e Silva, Y.R.; Paulino, P.V.R.; de Paula Sousa, D.; Possamai, A.J.; da Freiria, L.B.; Rolim, H.C.L.; de Castro Dias Júnior, W.; da Silva Cabral, L. Dried distiller’s grains for feedlot Nellore cattle fed non-forage-based diets. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, 230.

- Savian, J.V.; Schons, R.M.T.; Mezzalira, J.C.; Barth Neto, A.; Silva Neto, G.F.; Benvenutti, M.A.; Carvalho, P.C.F. A comparison of two rotational stocking strategies on the foraging behaviour and herbage intake by grazing sheep. Animal 2020, 14, 2503–2510.

- Yanai, A.M.; Graça, P.M.L.A.; Ziccardi, L.G.; Escada, M.I.S.; Fearnside, P.M. Brazil’s Amazonian deforestation: The role of landholdings in undesignated public lands. Reg. Environ. Change 2022, 22, 30.

- Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). Acompanhamento e a Análise de Impacto das Políticas Públicas—PPCDAm. 2017. Available online: http://redd.mma.gov.br/pt/acompanhamento-e-a-analise-de-impacto-das-politicas-publicas/ppcdam (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Embrapa. What is “ICLFS”? 2021. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/en/tema-integracao-lavoura-pecuaria-floresta-ilpf/nota-tecnica (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Aguiar, D. Boas Práticas Agropecuárias Impulsionam Ações em Plano Agrícola e Pecuário. Boas Práticas Agropecuárias Impulsionam Ações em Plano Agrícola e Pecuário—Portal Embrapa. 2012. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/en/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/1481822/boas-praticas-agropecuarias-impulsionam-acoes-em-plano-agricola-e-pecuario---#:~:text=O%20Plano%20indica%20que%20os%20ganhos%2C%20sist%C3%AAmicos%2C%20com,de%20sua%20inclus%C3%A3o%20no%20Plano%20Agr%C3%ADcola%20e%20Pecu%C3%A1rio (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (MAPA). Plano Agrícola e Pecuário 2010–2011. Agricultura é Sustentabilidade e Crescimento. 2010. Available online: https://www.bb.com.br/docs/pub/siteEsp/agro/dwn/PAP20102011.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Reis, J.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.R.; Marcela, C.G.C.; Martins, C.M.S. Integração lavoura-pecuária-floresta no Brasil: Uma estratégia de agricultura sustentável baseada nos conceitos da green economy initiative. Sustentabilidade Em Debate Embrapa Soils Brasiília 2016, 7, 58–73.

- Governo do Brasil (Gov.br). Ações do Plano. 2016. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sustentabilidade/plano-abc/acoes-do-plano (accessed on 30 November 2022).

- Finger, A.; Ely, C.; Bombardelli, L.; Dos Santos, W.; Schneider, I. Plano ABC—Agricultura de Baixo Carbono; Encitech: Halmstad, Sweden, 2016; Available online: https://www2.fag.edu.br/coopex/inscricao/arquivos/encitec/20161023-205240_arquivo.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Maio, A. Práticas Agropecuárias Sustentáveis Começam a Influenciar o Consumo de Carne No Brasil. 2019. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/en/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/46109238/praticas-agropecuarias-sustentaveis-comecam-a-influenciar-o-consumo-de-carne-no-brasil (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Sekaran, U.; Lai, L.; Ussiri, D.A.N.; Kumar, S.; Clay, S. Role of integrated crop-livestock systems in improving agriculture production and addressing food security—A review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 5, 100190.

- Garrett, R.D.; Niles, M.T.; Gil, J.D.B.; Gaudin, A.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Assmann, A.; Assmann, T.S.; Brewer, K.; Faccio Carvalho, P.C.D.; Cortner, O.; et al. Social and ecological analysis of commercial integrated crop livestock systems: Current knowledge and remaining uncertainty. Agric. Syst. 2017, 155, 136–146.

- Nepstad, D.; McGrath, D.; Sticker, C.; Alencar, A.; Azevedo, A.; Swette, B.; Bezerra, T.; Digiano, M.; Shimada, J.; Motta, R.S.; et al. Slowing amazon deforestation through public policy and interventions in beef an soy supply chains. Science 2014, 344, 1118–1123.

- Bungenstab, D.J. Brazilian Beef Cattle: Reducing Global Warming by the Production Systems Efficiency; Documents/Embrapa Gado de Corte; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2012; pp. 1–38. ISSN 1983-974X.

- Grandchamp, L. Principais Tipos de Crédito Rural e Suas Taxas de Juros. Dia Rural—Ao Lado do Agronegócio Brasileiro. 2021. Available online: https://diarural.com.br/principais-tipos-de-credito-rural-e-suas-taxas-de-juros/ (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Banco do Brasil. Moderagro. Crédito Para o Desenvolvimento do Seu Agronegócio. 2023. Available online: https://www.bb.com.br/pbb/pagina-inicial/agronegocios/agronegocio---produtos-e-servicos/grande-produtor/investir-em-sua-atividade/moderagro#/ (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Lins, C.F.; Moreira, S.N.; Leitão, T.F.S.; Almeida, A.N. Brazilian Forest Code: 1965–2012, from dictatorship to democracy. Rev. Foco. 2022, 15, 1–27.

- Valle, R.S.T.D. Código Florestal: Mudar é preciso. Mas para onde? In Código Florestal- Desafios e Perspectivas; Silva, S.T.D., Cureau, S., Leuzinger, M.D., Eds.; Fiuza: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010; pp. 1–360. ISBN 8562354082.

- Silva Júnior, J.P.; Aparecida, R.; Assis, R.B.; Santos, C.C.J. Histórico e Conceitos do Código Florestal de 1965. JUS. 2017. Available online: https://jus.com.br/artigos/58371/historico-e-conceitos-do-codigo-florestal-de-1965 (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Embrapa. Entenda a Lei 12.651 de 25 de Maio de 2012. 2013. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/codigo-florestal/entenda-o-codigo-florestal (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Governo do Brazil (Gov.br). Inscrever Imóvel Rural no Cadastro Ambiental Rural (CAR). 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/pt-br/servicos/inscrever-imovel-rural-no-cadastro-ambiental-rural-car (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Yalmanov, N. Public Policy and Policy-Making. In XXIII International Conference Culture, Personality, Society in the Conditions of Digitalization: Methodology and Experience of Empirical Research Conference; KnE Social Sciences: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2020; pp. 558–564.

- Ministerio do Meio Ambiente (MMA). Plano Setorial de Mitigação e de Adaptação às Mudanças Climáticas Para a Consolidação de Uma Economia de Baixa Emissão de Carbono Na Agricultura: Plano ABC (Agricultura de Baixa Emissão de Carbono). 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/sustentabilidade/plano-abc/plano-abc-agricultura-de-baixa-emissao-de-carbono (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- O Banco Nacional do Desenvolvimento (BNDES). Fundo Amazonia. In Documento do Projeto; 2013. Available online: https://www.fundoamazonia.gov.br/pt/fundo-amazonia/ (accessed on 6 December 2022).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!