Numerous dietary quality indices exist to help quantify overall dietary intake and behaviors associated with positive health outcomes. Most indices focus solely on biomedical factors and nutrient or food intake, and exclude the influence of important social and environmental factors associated with dietary intake. Using the Diet Quality Index- International as one sample index to illustrate the proposed holistic conceptual framework, this entry seeks to elucidate potential adaptations to dietary quality assessment by considering—in parallel—biomedical, environmental, and social factors. Considering these factors would add context to dietary quality assessment, influencing post-assessment recommendations for use across various populations and circumstances. Additionally, individual and population-level evidence-based practices could be informed by contextual social and environmental factors that influence dietary quality to provide more relevant, reasonable, and beneficial nutritional recommendations.

- dietary quality

- reductionism

- holism

- dietary quality index

1. Introduction

2. Reductionism vs. Holism

3. Diet Quality Index-International: Diet Index from a Holistic Perspective

4. Holistic Conceptual Framework for Dietary Quality Assessment

| Holistic Factors Contributing to Contextual Translation of Dietary Quality | ||

|---|---|---|

| Biomedical Factors | Social Factors | Environmental Factors |

| Health/Disease Status | Culture | Climate/Seasons |

| Genetics | Socioeconomics | Pollution/Contamination |

| Anthropometrics | Religion | Land Availability |

| Energy Balance | Food Preparation | Food Accessibility |

| Developmental Status | Food Processing | Food Safety/Regulation |

| Personal Attributes | Meal Patterns | Topography |

5. DQI-I: Contextual Translation of Dietary Quality Scores

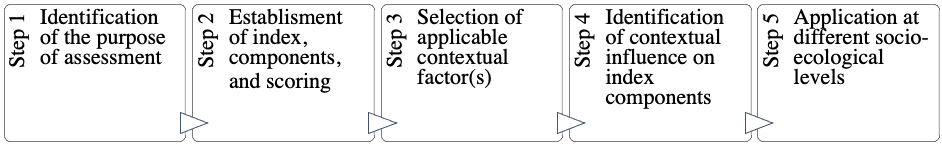

Some of the most popular dietary indices, such as the HEI, AHEI, and DASH Score indices, are most relevant to high-income countries that have access to plentiful food sources and food imports; therefore, these indices may not be relatable or applicable for low-income countries that struggle with food security [15]. The DQI-I is an index that allows users to customize measurements based upon country-specific guidelines. This customizability provides a foundation for additional considerations that could include other social and environmental contextual factors to provide a more holistic assessment. The DQI-I is used as a focused example index within this entry, specifically because of its applicability to various contexts. Other indices could also be modified using the conceptual framework suggested to incorporate other holistic factors. The process of how contextual considerations could be incorporated into dietary quality assessment through alterations, exclusions, modifications, and additions to the DQI-I are shown in Figure 1: Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process.

Figure 1. Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process.

The first step in the conceptual Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process is to identify the purpose or goal of the assessment to provide direction for the contextualization of overall dietary quality and how the assessment might be applied. Once the goal of the assessment has been identified, the next step is to select the most appropriate dietary index, including its components and scoring methods. For the examples researchers have provided, they used the DQI-I due to its applicability to different populations and settings [16] where this assessment process might be used [17]. The next step is to select a contextual factor or factors that are thought to potentially influence overall dietary quality. The factors listed in the assessment process model are nowhere near exhaustive of the biomedical, social, or environmental factors that could be present in a population. Additionally, it is understood that these factors are highly interconnected. Once the contextual factors have been identified for measurement, critical analysis of each index component should be conducted to determine what aspects of dietary quality may be influenced by the selected contextual factor, whether that be variety, adequacy, moderation, balance, or another index component. In other words, what components of the dietary index are being negatively affected due to the additional social or environmental factors. These considerations may add valuable context for evidence-based practices, allowing for translation of dietary quality scores to appropriate post-assessment recommendations, based on the social and environmental factors that influence dietary quality.

The following examples are hypothetical illustrations of how this conceptual assessment process might be use in different settings; specifically at the individual and community or societal levels of influence on health [18]. Table 2: Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process, Example 1: Community or Societal level, illustrates an example of a hypothetical community leader identifying potential reasons for poor dietary quality in their respective geographic location. Specifically, here researchers highlight rural areas where accessibility to healthful foods might be lacking, and how programming or policy changes might help to improve dietary quality at the community level. In order to determine accessibility, the United States Department of Agriculture: Economic Research Service’s “Food Data Atlas," [19] represents one way to identify areas of low income and areas of low accessibility to healthful foods. After completing the assessment process steps, the community leader could then determine what feasible, immediate, or minor changes could be made to increase the accessibility of healthful foods in their community. For example, reducing sales taxes on fresh produce or creating pop-up farmers markets within low-income, low-accessibility areas.

Table 2. Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process, Example 1: Community or Societal level.

|

Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process |

||||

|

Example 1: Community or Societal-level |

||||

|

Step 1: Identification of index, components, and scoring |

Step 2: Selection of applicable contextual factor/factors |

Step 3: Identification of contextual influence on index component |

||

|

Variety: (0-20pts) Overall variety (0-15pts) Within-group (0-5pts) |

Biomedical Health/ Disease Status Genetics Anthropometrics Energy Balance Developmental Status Personal Attributes

Social Culture Socioeconomics Religion Food Preparation Food Processing Meal Patterns

Environmental Climate/Seasons Pollution/Contamination Land Availability Food Accessibility Food Safety/Regulation Topography |

Variety (0-20pts)

|

→ |

The “within-group” variety for protein might be limited due to not including points for other protein sources such as grains, legumes, seeds, soy, or other geographic-specific protein sources. |

|

Adequacy: (0-40pts) Vegetable (0-5pts) Fruit (0-5pts) Grain (0-5pts) Fiber (0-5pts) Protein (0-5pts) Iron (0-5pts) Calcium (0-5pts) Vitamin C (0-5pts) |

||||

|

Adequacy (0-40pts)

|

→ |

Different types of nutritional data, such as a 24-hour recall, might alter the accuracy of this component due to accessibility issues differing from one day to another. A FFQ might be more appropriate during this context, as it allows the dietary quality score analyze intake over a period of time. |

||

|

Moderation: (0-30pts) Total Fat (0-6pts) Saturated Fat (0-6pts) Cholesterol (0-6pts) Sodium (0-6pts) Empty Calories (0-6pts) |

||||

|

Moderation (0-30pts)

|

→ |

Ready-to-eat foods or highly processed foods might be eaten more regularly due to difficulties accessing fresh produce. These foods are often high in saturated fats, sugars, sodium, and empty calories. |

||

|

Balance: (0-10pts) Macronutrient ratio (0-6pts) Fatty acid ratio (0-4pts) |

||||

|

Balance (0-10pts)

|

→ |

The types of foods potentially consumed when fresh produce is not readily available, such as foods with a long shelf-life, could contribute to an off balanced fatty acid ratio. |

||

To further demonstrate the assessment process, Table 3: Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process, Example 2: Individual level, illustrates a hypothetical practitioner helping an individual client who has lactose intolerance, and is living in a northern geographic area during winter. Through identification of barriers to achieving high dietary quality, such as decreased Vitamin D intake, the practitioner may focus on strategies to help increase dietary quality, such as switching to lactose-free dairy products, taking a Vitamin D supplement, or focusing on fortified foods. Additionally, by adding contextual factors the practitioner may identify a “ceiling” for the dietary quality that the client could potentially achieve, considering the factors that are in or out of that client’s control. This process could help to determine potential facilitators to improving dietary quality, making achievable recommendations to increase overall dietary quality. The goal would be able to maximize the potential dietary quality, recognizing that some factors would not be controllable and may not be easily modified.

Table 3. Conceptual Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process, Example 2: Individual level.

|

Holistic Dietary Quality Assessment Process |

||||

|

Example 2: Individual-level |

||||

|

Step 1: Identification of index, components, and scoring |

Step 2: Selection of applicable contextual factor/factors |

Step 3: Identification of contextual influence on index component |

||

|

Variety: (0-20pts) Overall variety (0-15pts) Within-group (0-5pts) |

Biomedical Health/Disease Status Genetics Anthropometrics Energy Balance Developmental Status Personal Attributes

Social Culture Socioeconomics Religion Food Preparation Food Processing Meal Patterns

Environmental Climate/Seasons Pollution/Contamination Land Availability Food Accessibility Food Safety/Regulation Topography |

Variety (0-20pts)

|

→ |

Variety score might be low due to low accessibility to in-season fruits and vegetables. |

|

Adequacy: (0-40pts) Vegetable (0-5pts) Fruit (0-5pts) Grain (0-5pts) Fiber (0-5pts) Protein (0-5pts) Iron (0-5pts) Calcium (0-5pts) Vitamin C (0-5pts) |

||||

|

Adequacy (0-40pts)

|

→ |

Special consideration might be given to foods that are plentiful sources of Vitamin D. |

||

|

Moderation: (0-30pts) Total Fat (0-6pts) Saturated Fat (0-6pts) Cholesterol (0-6pts) Sodium (0-6pts) Empty Calories (0-6pts) |

||||

|

Moderation (0-30pts)

|

→ |

Some of the foods that would still contribute to increased health could also contain high amounts of sodium, such as canned vegetables. |

||

|

Balance: (0-10pts) Macronutrient ratio (0-6pts) Fatty acid ratio (0-4pts) |

||||

|

Balance (0-10pts)

|

→ |

Ratios could be off-balanced if the person is unable to consume specific foods. |

||

6. Cross-Population Comparisons

The flexibility for dietary quality scoring to be based on country-specific guidelines, when used within the context of a larger, uniform scale, provides a foundation for a holistic conceptual framework for evaluation across different cultures and populations. A more holistic and useful analysis of dietary quality may be possible when evaluation of dietary quality: 1) includes contextual social and environmental factors according to country or region, based on their specific dietary guidelines or the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) guidelines; and 2) considers variety, adequacy, moderation, and balance. Further, this more contextualized and holistic approach may allow insights regarding explanatory mechanisms behind dietary quality differences than are typically gleaned from assessments of dietary quality. For example, if a study were to evaluate the dietary quality of high-income countries (e.g., Canada) or populations where there is access to a large variety of imported foods, versus populations from a desert climate, low-income country (e.g., Libya) with few imported food products, dietary intakes and guidelines would likely differ drastically. While it is possible that indices of dietary quality could be modified to add biomedical, social, and environmental factors in order to provide a more holistic assessment, another potential approach would be to utilize previously designed dietary quality indices, with minor modifications, alongside separate tools that assess social and environmental factors anytime dietary quality is assessed. For example, if a practitioner suspects that a social or environmental factor may be a barrier to achieving high dietary quality scores, this conceptual framework may be used to determine what contextual factors are present, thereby allowing alterations to post-assessment recommendations and potential interventions.

7. Conclusions

The purpose of the current entry was not to offer a definitive solution for the problem of poor dietary quality, but rather to shine a light on the need to further inquire about how researchers might accomplish the inclusion of contextual factors when seeking to understand the barriers and facilitators for optimizing dietary quality. Considering contextual factors alongside adherence to dietary guidelines in dietary quality assessment could strengthen the core of evidence-based practices. Evidence-based practices are essential for providing high-quality care, guiding development of policy, determining preventive practices, and much more. Improved understanding of individual and population-level goals, expectations, preferences, accessibility, and resources, through evidence-based nutrition practices, will produce reasonable, applicable, and beneficial nutritional recommendations. A holistic approach to dietary quality assessment may allow nutrition professionals to better identify areas for improvement, such as potential barriers contributing to poor adherence to guidelines within dietary intervention studies, or specific population needs for overcoming barriers to positive health outcomes. If dietary quality is substantially hindered due to social or environmental factors, public health officials could use these data to work toward mitigating barriers to the extent possible. Further, identification of populations who are doing well with regard to dietary quality, even while facing social or environmental challenges, could assist nutrition scientists in advising government agency professionals developing future dietary guidelines.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph20053986

References

- World Health Organization. Non-Communicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Global Ncds. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ncd/global-ncd-overview.html (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Scrinis, G. Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. Perspective: Reductionist Nutrition Research Has Meaning Only within the Framework of Holistic and Ethical Thinking. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 655–670.

- Hoffmann, I. Transcending Reductionism in Nutrition Research. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 514S–516S.

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. From a Reductionist to a Holistic Approach in Preventive Nutrition to Define New and More Ethical Paradigms. Healthcare 2015, 3, 1054–1063.

- Fardet, A.; Rock, E. Toward a New Philosophy of Preventive Nutrition: From a Reductionist to a Holistic Paradigm to Improve Nutritional Recommendations. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 430–446.

- Jacobs, D.R.; Gross, M.D.; Tapsell, L.C. Food Synergy: An Operational Concept for Understanding Nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1543S–1548S.

- Jacobs, D.R.; Tapsell, L.C.; Temple, N.J. Food Synergy: The Key to Balancing the Nutrition Research Effort. Public Health Rev. 2011, 33, 507–529.

- Fardet, A.; Lakhssassi, S.; Briffaz, A. Beyond Nutrient-Based Food Indices: A Data Mining Approach to Search for a Quantitative Holistic Index Reflecting the Degree of Food Processing and Including Physicochemical Properties. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 561–572.

- Kim, S.; Haines, P.S.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Popkin, B.M. The Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) Provides an Effective Tool for Cross-National Comparison of Diet Quality as Illustrated by China and the United States. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3476–3484.

- Alipour Nosrani, E.; Majd, M.; Bazshahi, E.; Mohtashaminia, F.; Moosavi, H.; Ramezani, R.; Shahinfar, H.; Djafari, F.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Djazayery, A. The Association between Meal-Based Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) with Obesity in Adults. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 156.

- Cho, I.Y.; Lee, K.M.; Lee, Y.; Paek, C.M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, K.; Han, J.S.; Bae, W.K. Assessment of Dietary Habits Using the Diet Quality Index—International in Cerebrovascular and Cardiovascular Disease Patients. Nutrients 2021, 13, 542.

- Setayeshgar, S.; Maximova, K.; Ekwaru, J.P.; Gray-Donald, K.; Henderson, M.; Paradis, G.; Tremblay, A.; Veugelers, P. Diet Quality as Measured by the Diet Quality Index–International Is Associated with Prospective Changes in Body Fat among Canadian Children. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 456–463.

- Guerrero, M. L. P., & Pérez-Rodríguez, F. (2017). Diet Quality Indices for Nutrition Assessment: Types and Applications. Functional Food - Improve Health through Adequate Food. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.69807

- Kim, S.; Haines, P.S.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Popkin, B.M. The Diet Quality Index-International (DQI-I) Provides an Effective Tool forCross-National Comparison of Diet Quality as Illustrated by China and the United States. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3476–3484.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020– 2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_ Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- McCloskey, D.J.; McDonald, M.A.; Cook, J.; Heurtin-Roberts, S.; Updegrove, S.; Sampson, D.; Gutter, S. Definitions and Organizing Concepts from the Literature. 40. Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_intro. html (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- USDA. Economic Research Service Food Access Research Atlas; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.