You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Several risk factors have been identified in sporadic AD; aging is the main one. Nonetheless, multiple genes have been associated with the different neuropathological events involved in LOAD, such as the pathological processing of Amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide and Tau protein, as well as synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunctions, neurovascular alterations, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation, among others. Interestingly, using genome-wide association study (GWAS) technology, many polymorphisms associated with LOAD have been identified

- Alzheimer’s disease

- genetics

- GWAS

- loci

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and represents the most common form of dementia (60–80% of all cases of dementia) [1]. At present, an estimated 50 million people worldwide suffer from some form of dementia; however, as a result of the increase in life expectancy rates, it is expected that by 2050, 139 million people worldwide will suffer from some type of dementia [2][3], which will cause major socioeconomic and health system impacts [4].

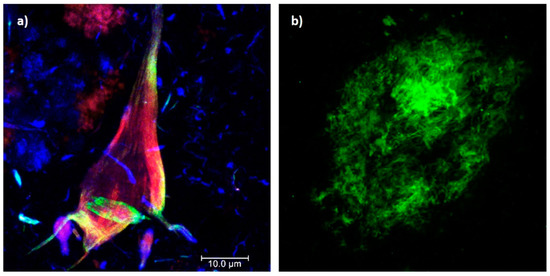

AD is characterized by chronic and acquired memory impairment and cognitive deficits in domains, such as language, spatio-temporal orientation, and executive capacity, as well as behavior alterations, all of which lead to progressive loss of personal autonomy [5]. Histopathologically, AD is characterized by two pathognomonic hallmarks (Figure 1) [6]: (1) the intracellular deposition of abnormally phosphorylated Tau protein that promotes the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the cerebral cortex and subcortical gray matter (Figure 1a); and (2) extracellular aggregates of Amyloid-beta peptide (Aβ) fibrils in the form of neuritic plaques (NPs; Figure 1b). In this context, it has been postulated that endogenous “damage signals”, such as Aβ oligomers, could cause the activation of microglial cells with the consequent release of proinflammatory cytokines, which would trigger signaling cascades in neurons causing hyperphosphorylation and the aggregation of Tau protein. This protein is released when neurons die, triggering microglial cell activation and, therefore, becomes a cyclic pathological process that culminates in neurodegeneration [7][8]. Therefore, both NPs and NFTs are involved in several neuronal processes and ultimately trigger neuronal death [9][10], synaptic alteration, oxidative stress, mitochondrial disturbance, neuroinflammation, alterations in the permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and neurovascular unit dysfunction [11].

Figure 1. Histopathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. (a) Triple immunofluorescence showing a neurofibrillary tangle (conformational change: green channel; C-terminal tail: red channel; N-terminal of intact tau protein: blue channel). (b) Immunofluorescence showing an amyloid plaque (Aβ 1-40: green channel). Photomicrographs at 100X, calibration bar = 10 µm.

Two forms of AD have been characterized [6]: familial and sporadic. The familial presentation is autosomal dominant, early onset (EOAD) in individuals under 65 years of age (representing 1 to 5% of cases), and characterized by the alteration of specific genes, such as the presenilin 1 gene (PSEN1, 14q24.2), identified in up to 70% of cases with familial AD; the presenilin 2 gene (PSEN2, 1q42.13) and the Amyloid precursor protein gene (APP, 21q21.3). The sporadic presentation is late-onset (LOAD) and occurs in individuals older than 65 years of age. The main risk factor is considered to be age [1][9][12], but sporadic AD is a complex disorder and other risk factors have been identified, such as the female sex, traumatic brain injury, depression, environmental pollution, physical inactivity, social isolation, low academic level, metabolic syndrome [9][13] and genetic susceptibility, mainly mutations in the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE, 19q13.32) [1][9], considering a heritability of up to 60–80% [14].

Multiple hypotheses have been formulated to explain the development of AD, including the amyloidogenic cascade, tauopathy, vascular theory, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and bacterial infections theory, among others [6][11][15]. However, due to the intricate complexity of the human brain and partial characterization of the polymorphisms associated with AD, the molecular mechanisms involved in each of these hypotheses and their correlation with the genetic load or predisposition of each individual are poorly understood [16]. Therefore, characterizing the genetic risk factors in AD is a priority to understand the several neuropathological events involved.

Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have allowed the identification of several genes associated with AD; however, the relationship of many loci to the risk of developing AD has not been elucidated [17].

2. Impact of GWAS on Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease

From 2005 to the present, multiple genetic studies have tracked most of the genes that conform to the human genome. These genetic studies are known as Genome-wide Association Studies (GWAS) and their objective is to associate certain genes with multiple pathologies or disorders [18][19]. Until 2007, only mutations in the APOE-ε4 allele were reliably associated with increased susceptibility to LOAD. Nonetheless, to date, multiple analyses have been performed with GWAS technology, demonstrating many possible genes associated with LOAD. Targeted genetic approaches and next-generation sequencing studies have also identified several low-frequency genes that are associated with a relatively high risk of developing AD, therefore providing insight into the pathogenesis [5]. GWAS have associated more than 40 risk alleles with AD, identifying variants that trigger neurodegeneration, such as lipid metabolism, inflammation, innate immunity, Aβ production and clearance, and endosomal vesicle recycling [20][21]. In particular, GWAS have also allowed us to identify those genes related to the development of both EOAD and LOAD [14].

Since genetic variations have been evidenced between different ethnic groups [22], it is essential that researchers perform GWAS in AD across ethnicities and identify polymorphisms associated with each of them. In Table 1, note that most GWAS analyses have been conducted in the Caucasian population and, therefore, are biased by not including other populations and determining the susceptibility of other possible genetic variations involved. The African American population is twice as likely to develop the disease [14]; hence, it is necessary to increase the studies on these populations. In the same way, only one of the studies [23] focused on identifying possible genes involved in AD taking into account the gender of the patients, although women are at a higher risk of developing AD and have worse clinical and pathological outcomes [24]. In addition, some of these studies could be biased, as the sample between controls and patients with AD was not balanced and neither were the risk factors or modifiers of the study subjects, including comorbidities, gender, age range, environmental exposure, and medication, among others.

On the other hand, GWAS have allowed the identification of genetic components that are not related to the neuropathological processes mentioned above, affecting only cognitive reserve, which refers to individual differences in susceptibility to age-related brain changes or AD-related pathology [25]; thus, some people would tolerate more of these changes and still maintain function. In this context, growing evidence suggests that, among cognitively healthy patients with a genetic risk of developing AD, women exhibit better global cognition than men. This event is maintained during the early stages of the disease, despite showing increased Tau pathology, hippocampal atrophy, and metabolic dysfunction [24]. This indicates that although women have greater resilience to the disease, there are still unidentified factors that cause them to have a greater risk of developing the disease.

Although GWAS have been invaluable in identifying candidate genetic variants associated with the disease, the AD risk loci identified to date explain only a small fraction of the heritability of AD [26]; therefore, part of it remains unexplained. One solution would be to increase the sample size of GWAS, as they have already been used to characterize new genetic risk factors in other diseases [14]. Interestingly, GWAS in AD have transitioned from identifying only a couple of novel genes to identifying a large number of previously unreported associations. This is probably due to an increase in the size of the samples and the diversification of the populations studied.

However, the increase in sample size is due to the use of a Russian doll-like design where larger studies include all smaller studies [27], which could limit results when analyzing the same samples multiple times instead of generating new patient data. In support of this, some GWAS [14][26][28][29] have shown that the use of a proxy patient (self-report of the parental history of AD) is useful to favor an increase in the sample size without affecting the validity of the results.

Therefore, future GWAS must adopt a better definition of cases and controls, as well as designs based on the comparison of ethnic groups, sex, and age, since there may be various environmental, exposure, and genetic factors that modify the risk load conferred by each locus. Likewise, these associations should be replicated and validated in multiple populations and followed by a downstream functional dissection to benefit knowledge of pathophysiology [30].

Table 1. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for Alzheimer’s disease.

| Year | Population (Ethnicity/Race) | New Genes Found * | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | British and Americans (n = 3870); LOAD = 1808; Ctrl = 2062 | APOE | [31] |

| 2008 | European ancestry (n = 1376). | CD33 | [32] |

| 2009 | 1. French (n = 7360); LOAD = 2032; Ctrl = 5238 2. Belgians, Finns, Italians, Spanish (n = 7275); LOAD = 3978; Ctrl = 3297 |

CR1, CLU | [33] |

| 2009 | 1. British, Germans, and Americans (n = 11,789); LOAD = 3941; Ctrl = 7848 2. Europeans (n = 4372); LOAD = 2032; Ctrl = 2340. |

PICALM | [34] |

| 2010 | Spanish (n = 2349); LOAD = 1140; Ctrl = 1209 | EXOC3L2, BIN1 | [35] |

| 2010 | Caucasians of German extraction (n = 970); LOAD = 491; Ctrl = 479 | TOMM40 | [36] |

| 2011 | 1. Europeans (n = 9799); LOAD = 4896; Ctrl = 4903 2. Europeans (n = 29,544); LOAD = 8286; Ctrl = 21,258 |

ABCA7, MS4A6, EPHA1, CD2AP | [37] |

| 2011 | European Americans (n = 3839); LOAD = 1848; Ctrl = 1991 | CUGBP2 | [38] |

| 2011 | 1. African Americans (n = 1009); LOAD = 513; Ctrl = 496 2. White (n = 9773); LOAD = 3568; Ctrl = 6205 |

PVRL2 | [39] |

| 2012 | Caribbean Hispanics (n = 1093); LOAD = 549; Ctrl = 544 | DGKB, GWA-10q23.1 (PCDH21, LRIT1, RGR), HPCAL1 | [40] |

| 2012 | Polish (n = 282); Cases = 141 (94 LOAD, and 47 MCI); Ctrl = 141 | GWA-9q21.33 | [41] |

| 2012 | 1. European Americans (n = 2440); LOAD = 1440; Ctrl = 1000 2. European Americans (n = 6063); LOAD = 2727; Ctrl = 3336 |

PPP1R3B | [42] |

| 2013 | European ancestry and African Americans (n = 4689); LOAD = 2493; Ctrl = 2196 | PLD3 | [43] |

| 2013 | 1. Icelanders (n = 4786); LOAD = 3550; Ctrl = 1236. 2. Americans, Norwegians, Germans, Dutch (n = 11,764); LOAD = 2037; Ctrl = 9727 |

TREM2 | [44] |

| 2014 | European Americans (n = 3656); LOAD = 2151; Ctrl = 1505 | APOC1, CAMK1D, FBXL13 | [45] |

| 2014 | Multiethnic (mostly Caucasians; n = 32,346); LOAD = 14,967; Ctrl = 17,379 | PLXNA4 | [46] |

| 2015 | 1. Caribbean Hispanics (n = 4514); LOAD = 2451; Ctrl = 2063 2. Caribbean Hispanics (n = 5300); LOAD = 3001; Ctrl = 2299 |

FBXL7, FRMD4A, CELF1, FERMT2, SLC24A4-RIN3. | [47] |

| 2015 | Japanese (n = 8808); LOAD = 816; Ctrl = 7992 | CNTNAP2, GWA-18p11.32, GWA-12q24.23 | [48] |

| 2016 | European ancestry (n = 3467) LOAD = 2488; Ctrl = 979 | OSBPL6, PTPRG, PDCL3, | [49] |

| 2017 | African Americans (n = 5609); LOAD = 1825; Ctrl = 3784 | COBL, SLC10A2 | [28] |

| 2018 | Multiethnic (n = 54,162); LOAD = 17,008; Ctrl = 37,154 | MLH3, FNBP4, CEACAM19, CLPTM1. | [50] |

| 2018 | British. Maternal AD = 27,696; Ctrl = 260,980 Paternal AD= 14,338; Ctrl = 245,941 |

ADAM10, BCKDK/KAT8 (VKORC1), ACE, TREML2, PLCG2, IL-34. | [29] |

| 2019 | European ancestry (n = 455,258); LOAD = 71,880; Controls = 383,378 | ADAMTS4, INPP5D, HESX1, CLNK, HS3ST1, HLA-DRB1, ZCWPW1 (SPDYE3), CNTNAP2, CLU/PTK2B, ECHDC3, APH1B, SCIMP, AB13, BZRAP1-AS1, SUZ12P1, ALPK2, AC074212.3. | [26] |

| 2019 | Caucasian ancestry (n = 17,480); LOAD = 2741; Ctrl = 14,739 | CEACAM16, BCL3, MIR8085, CBLC, BCAM, PVRL2, APOC1, APOC1P1, APOC4, APOC2, LINC00158, MIR155HG, MIR155, LINC00515, MRPL39, JAM2, C2orf74, ATG10, MS4A6A, ABCB9, ZNF815, TRA2A, MED30, LPXN, IRAK3, N4BP2L2, UQCC, APOBEC3F, SFNa, ESPN, GNAI3, C9orf72, MTMR3 | [23] |

| 2019 | Non-Hispanic Whites (n = 94,437); LOAD = 35,274; Ctrl = 59,163 | NYAP1 (SPDYE3), ECHDC3 (USP6NL), IQCK, WWOX. | [51] |

| 2020 | African Americans (n = 8006); LOAD = 2784; Ctrl = 5222 | TRANK1, FABP2, LARP1B, TSRM, ARAP1, STARD10, SPHK1, SERPINB13, EDEM1, ALCAM, GPC6, VRK3, SIPA1L2, WDR70, API5, ACER3, PIK3C2G, ARRDC4, IGF1R, RBFOX1, MSX2, AKAP9. | [52] |

| 2021 | British (n = 495,000); LOAD = 75,000; Ctrl = 420,000 |

PILRA, NCK2, SPI1, TSPAN14, SPPL2A, ACE, CCDC6, ADAMTS1, SHARPIN, GRN, SPRED2, ADAMTS4, TMEM163, SIGLEC11, PLCG2, IGHG1, IKZF1, TSPOAP1. | [20] |

| 2022 | Japanese (n = 3777); LOAD = 1744; Ctrl = 2033 | FAM126A, ZFHX4, LGR5, ZFC3H1, OR51G1, OR4X2, ARHGEF4, PRUNE2, MLKL, NCOR2, DMD, NEDD4, PLEC | [53] |

| 2022 | European (n = 788,989); LOAD = 111,326; Ctrl = 677,663 | UNC5CL, EPDR1, WNT3, SORT1, ADAM17, PRKD3, MME, IDUA, RHOH, ANKH, COX7C, TNIP1, RASGEF1C, HS3STS, UMAD1, ICA1, TMEM106B, JAZF1, SEC61G, CTSB, ABCA1, ANK3, BLNK, PLEKHA1, TPCN1, SNX1, DOC2A, MAF, FOXF1, PRDM7, WDR91, MYO15A, KLF16, LILRB2, RBCK1, SLC2A4RG, APP. | [14] |

Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer’s disease; Ctrl: controls; LOAD: Late-onset Alzheimer disease; MCI: Mild cognitive impairment. * Only newly identified genes are shown.

Furthermore, studies that have made associations between genetics and epigenetics through epigenome-wide assays should not be left aside. DNA methylation, an epigenetic modification, plays an important role in regulating gene expression and thus in a wide range of diseases and biological processes [54]. Interestingly, one of these analyses was conducted in a Mexican-American population with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [55], finding various methylation regions between control and MCI patients, as well as some genes involved in neuronal death, metabolic dysfunction, and inflammatory processes. Highlighting that methylation is transgenerationally heritable and affected by environmental factors [54][56], these processes could explain not only the relationship of genetics with the disease, but also its relationship with environmental and lifestyle factors. For example, exposure to organophosphate pesticides has been shown to promote Tau hyperphosphorylation and microtubule dysfunction [57]. Likewise, it has been shown that the methylation of genes, including ABCA7, BIN1, SORL1, and SLC24A4, were significantly associated with the pathological processing of Tau protein and Aβ peptide. In addition, it was demonstrated that histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibitors could increase the level of histone acetylation, and thus have different beneficial effects on AD [58]: (i) improve the expression of genes related to memory; (ii) prevent cognitive degeneration; (iii) decrease the deposition of the Aβ peptide; and (iv) avoid hyperphosphorylation of the Tau protein and the NFT formation. Therefore, the identification of polymorphisms associated with multiple environmental factors through GWAS could favor the development of effective diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

However, GWAS present certain limitations [59]: (1) they eventually involve the entire genome in disease predisposition; (2) the identification of multiple loci without a clear mechanism can be uninformative and cause confusion with respect to AD; (3) the vast majority of GWAS focus on the European population and lack population stratification; and (4) the scarce data can lead to the fact that the heritability of diseases is not fully explained and therefore fail to detect epistasis in humans, which is the main component of the genetic architecture of complex traits [60].

Despite these limitations, as has been analyzed throughout the manuscript, GWAS have multiple benefits given their diverse clinical applications and allow the identification of new biological mechanisms as well as ethnic variations in the health-disease process. Similarly, GWAS should be promoted in understudied populations, with a different methodological and study design, larger sample sizes, with more clinical data, and extrapolating the associations identified to in silico and preclinical models to take full advantage of the potential this technology offers us.

Notwithstanding the significant advances in our understanding of AD pathobiology through GWAS technology, we have yet to identify a disease-modifying therapy that has demonstrated efficacy in humans. Most of the research conducted over the past 30 years has focused on anti-Aβ therapies [61]; however, all clinical trials with anti-Aβ therapies have been unsuccessful [62]. There are several reasons why these therapies may have failed [16][61]: (i) they are administered too late in the course of the disease when neuronal damage has already become irreversible; (ii) the misfolding and accumulation of the Aβ peptide is not the only cause of neurodegeneration and therefore it is not clear whether the reduction of Aβ levels effectively treats the disease; and (iii) since Aβ is produced by multiple pathways, inhibiting its production is complex. Despite the factors listed above, an IgG1 Aβ monoclonal antibody recently proved effective in phase 3 clinical trials to reduce AD biomarkers and reduce cognitive decline [63] and has already been approved for the treatment of AD by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) [64].

The multiple genes identified by GWAS support the various theories that have been postulated to explain the development of AD, some of them involved in more than one mechanism, such as PICALM, CLU, and CD2AP, among others (Table 1). This supports the hypothesis that the disease and its treatment should be considered from the multiconvergent theory and not through isolated mechanisms. It has been proposed that our genetic program should protect us from diseases, such as AD by working better under the conditions under which it was designed [65]; however, multiple behavioral and environmental factors could play a greater role in the development of the disease than their consideration by single mechanisms. This becomes even more important due to the aforementioned fact that most therapies against a single mechanism continue to show limited success and, therefore, understanding the disease from a unified theory would improve the results of preventive and therapeutic measures. In this context, multiple pathway-directed therapies may be more effective in slowing or preventing the progression of AD. For example, combined therapy with anti-Tau drugs, such as anti-amyloids, has been suggested, as well as the combination of neuroprotective drugs with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative stress effects [66].

On the other hand, it should be noted that genetics is only one factor that can influence the treatment of AD, since other factors, such as age, general state of health, and stage of the disease, can also influence the efficacy of the treatment. Similarly, the use of more general approaches to prevent or delay the onset of AD, such as lifestyle interventions or changes to prevent or delay the onset of AD [12], could be useful: maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and participating in cognitively stimulating activities [67][68][69].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms24043754

References

- 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 700–789.

- GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 88–106.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Matthews, K.A.; Xu, W.; Gaglioti, A.H.; Holt, J.B.; Croft, J.B.; Mack, D.; McGuire, L.C. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged >/=65 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2019, 15, 17–24.

- Lane, C.A.; Hardy, J.; Schott, J.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 59–70.

- Long, J.M.; Holtzman, D.M. Alzheimer Disease: An Update on Pathobiology and Treatment Strategies. Cell 2019, 179, 312–339.

- Maccioni, R.B.; Tapia, J.P.; Guzman-Martinez, L. Pathway to Tau Modifications and the Origins of Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2018, 49, 130–131.

- Gonzalez, A.; Singh, S.K.; Churruca, M.; Maccioni, R.B. Alzheimer’s Disease and Tau Self-Assembly: In the Search of the Missing Link. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4192.

- Silva, M.V.F.; Loures, C.M.G.; Alves, L.C.V.; de Souza, L.C.; Borges, K.B.G.; Carvalho, M.D.G. Alzheimer’s disease: Risk factors and potentially protective measures. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 33.

- Reiss, A.B.; Arain, H.A.; Stecker, M.M.; Siegart, N.M.; Kasselman, L.J. Amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 29, 613–627.

- Soto-Rojas, L.O.; Pacheco-Herrero, M.; Martinez-Gomez, P.A.; Campa-Cordoba, B.B.; Apatiga-Perez, R.; Villegas-Rojas, M.M.; Harrington, C.R.; de la Cruz, F.; Garces-Ramirez, L.; Luna-Munoz, J. The Neurovascular Unit Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2022.

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5789.

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734.

- Bellenguez, C.; Kucukali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436.

- Du, X.; Wang, X.; Geng, M. Alzheimer’s disease hypothesis and related therapies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2018, 7, 2.

- Sharma, P.; Srivastava, P.; Seth, A.; Tripathi, P.N.; Banerjee, A.G.; Shrivastava, S.K. Comprehensive review of mechanisms of pathogenesis involved in Alzheimer’s disease and potential therapeutic strategies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 174, 53–89.

- Wingo, A.P.; Liu, Y.; Gerasimov, E.S.; Gockley, J.; Logsdon, B.A.; Duong, D.M.; Dammer, E.B.; Robins, C.; Beach, T.G.; Reiman, E.M.; et al. Integrating human brain proteomes with genome-wide association data implicates new proteins in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 143–146.

- Bekdash, R.A. Early Life Nutrition and Mental Health: The Role of DNA Methylation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3111.

- Iraola-Guzman, S.; Estivill, X.; Rabionet, R. DNA methylation in neurodegenerative disorders: A missing link between genome and environment? Clin. Genet. 2011, 80, 1–14.

- Schwartzentruber, J.; Cooper, S.; Liu, J.Z.; Barrio-Hernandez, I.; Bello, E.; Kumasaka, N.; Young, A.M.H.; Franklin, R.J.M.; Johnson, T.; Estrada, K.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis, fine-mapping and integrative prioritization implicate new Alzheimer’s disease risk genes. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 392–402.

- Jia, L.; Li, F.; Wei, C.; Zhu, M.; Qu, Q.; Qin, W.; Tang, Y.; Shen, L.; Wang, Y.; Shen, L.; et al. Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease using multi-variants from a Chinese genome-wide association study. Brain 2021, 144, 924–937.

- Huang, T.; Shu, Y.; Cai, Y.D. Genetic differences among ethnic groups. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1093.

- Nazarian, A.; Yashin, A.I.; Kulminski, A.M. Genome-wide analysis of genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s disease and related sex disparities. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 5.

- Vila-Castelar, C.; Tariot, P.N.; Sink, K.M.; Clayton, D.; Langbaum, J.B.; Thomas, R.G.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, K.; Hu, N.; et al. Sex differences in cognitive resilience in preclinical autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease carriers and non-carriers: Baseline findings from the API ADAD Colombia Trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 2272–2282.

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 1006–1012.

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hagg, S.; Athanasiu, L.; et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 404–413.

- Escott-Price, V.; Hardy, J. Genome-wide association studies for Alzheimer’s disease: Bigger is not always better. Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac125.

- Mez, J.; Chung, J.; Jun, G.; Kriegel, J.; Bourlas, A.P.; Sherva, R.; Logue, M.W.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Buxbaum, J.D.; et al. Two novel loci, COBL and SLC10A2, for Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 13, 119–129.

- Marioni, R.E.; Harris, S.E.; Zhang, Q.; McRae, A.F.; Hagenaars, S.P.; Hill, W.D.; Davies, G.; Ritchie, C.W.; Gale, C.R.; Starr, J.M.; et al. GWAS on family history of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 99.

- Gallagher, M.D.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S. The Post-GWAS Era: From Association to Function. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 717–730.

- Grupe, A.; Abraham, R.; Li, Y.; Rowland, C.; Hollingworth, P.; Morgan, A.; Jehu, L.; Segurado, R.; Stone, D.; Schadt, E.; et al. Evidence for novel susceptibility genes for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease from a genome-wide association study of putative functional variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 865–873.

- Bertram, L.; Lange, C.; Mullin, K.; Parkinson, M.; Hsiao, M.; Hogan, M.F.; Schjeide, B.M.; Hooli, B.; Divito, J.; Ionita, I.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis reveals putative Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility loci in addition to APOE. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008, 83, 623–632.

- Lambert, J.C.; Heath, S.; Even, G.; Campion, D.; Sleegers, K.; Hiltunen, M.; Combarros, O.; Zelenika, D.; Bullido, M.J.; Tavernier, B.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1094–1099.

- Harold, D.; Abraham, R.; Hollingworth, P.; Sims, R.; Gerrish, A.; Hamshere, M.L.; Pahwa, J.S.; Moskvina, V.; Dowzell, K.; Williams, A.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1088–1093.

- Seshadri, S.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Ikram, M.A.; DeStefano, A.L.; Gudnason, V.; Boada, M.; Bis, J.C.; Smith, A.V.; Carassquillo, M.M.; Lambert, J.C.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2010, 303, 1832–1840.

- Feulner, T.M.; Laws, S.M.; Friedrich, P.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Wurst, S.H.; Riehle, C.; Kuhn, K.A.; Krawczak, M.; Schreiber, S.; Nikolaus, S.; et al. Examination of the current top candidate genes for AD in a genome-wide association study. Mol. Psychiatry 2010, 15, 756–766.

- Hollingworth, P.; Harold, D.; Sims, R.; Gerrish, A.; Lambert, J.C.; Carrasquillo, M.M.; Abraham, R.; Hamshere, M.L.; Pahwa, J.S.; Moskvina, V.; et al. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 429–435.

- Wijsman, E.M.; Pankratz, N.D.; Choi, Y.; Rothstein, J.H.; Faber, K.M.; Cheng, R.; Lee, J.H.; Bird, T.D.; Bennett, D.A.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; et al. Genome-wide association of familial late-onset Alzheimer’s disease replicates BIN1 and CLU and nominates CUGBP2 in interaction with APOE. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001308.

- Logue, M.W.; Schu, M.; Vardarajan, B.N.; Buros, J.; Green, R.C.; Go, R.C.; Griffith, P.; Obisesan, T.O.; Shatz, R.; Borenstein, A.; et al. Multi-Institutional Research on Alzheimer Genetic Epidemiology Study, G. A comprehensive genetic association study of Alzheimer disease in African Americans. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 1569–1579.

- Lee, J.H.; Cheng, R.; Barral, S.; Reitz, C.; Medrano, M.; Lantigua, R.; Jimenez-Velazquez, I.Z.; Rogaeva, E.; St George-Hyslop, P.H.; Mayeux, R. Identification of novel loci for Alzheimer disease and replication of CLU, PICALM, and BIN1 in Caribbean Hispanic individuals. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 320–328.

- Gaj, P.; Paziewska, A.; Bik, W.; Dabrowska, M.; Baranowska-Bik, A.; Styczynska, M.; Chodakowska-Zebrowska, M.; Pfeffer-Baczuk, A.; Barcikowska, M.; Baranowska, B.; et al. Identification of a late onset Alzheimer’s disease candidate risk variant at 9q21.33 in Polish patients. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 32, 157–168.

- Kamboh, M.I.; Demirci, F.Y.; Wang, X.; Minster, R.L.; Carrasquillo, M.M.; Pankratz, V.S.; Younkin, S.G.; Saykin, A.J.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging, I.; Jun, G.; et al. Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e117.

- Cruchaga, C.; Karch, C.M.; Jin, S.C.; Benitez, B.A.; Cai, Y.; Guerreiro, R.; Harari, O.; Norton, J.; Budde, J.; Bertelsen, S.; et al. Rare coding variants in the phospholipase D3 gene confer risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2014, 505, 550–554.

- Jonsson, T.; Stefansson, H.; Steinberg, S.; Jonsdottir, I.; Jonsson, P.V.; Snaedal, J.; Bjornsson, S.; Huttenlocher, J.; Levey, A.I.; Lah, J.J.; et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 107–116.

- Floudas, C.S.; Um, N.; Kamboh, M.I.; Barmada, M.M.; Visweswaran, S. Identifying genetic interactions associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. BioData Min. 2014, 7, 35.

- Jun, G.; Asai, H.; Zeldich, E.; Drapeau, E.; Chen, C.; Chung, J.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.; Haroutunian, V.; Foroud, T.; et al. PLXNA4 is associated with Alzheimer disease and modulates tau phosphorylation. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 379–392.

- Tosto, G.; Fu, H.; Vardarajan, B.N.; Lee, J.H.; Cheng, R.; Reyes-Dumeyer, D.; Lantigua, R.; Medrano, M.; Jimenez-Velazquez, I.Z.; Elkind, M.S.; et al. F-box/LRR-repeat protein 7 is genetically associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2015, 2, 810–820.

- Hirano, A.; Ohara, T.; Takahashi, A.; Aoki, M.; Fuyuno, Y.; Ashikawa, K.; Morihara, T.; Takeda, M.; Kamino, K.; Oshima, E.; et al. A genome-wide association study of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a Japanese population. Psychiatr. Genet. 2015, 25, 139–146.

- Herold, C.; Hooli, B.V.; Mullin, K.; Liu, T.; Roehr, J.T.; Mattheisen, M.; Parrado, A.R.; Bertram, L.; Lange, C.; Tanzi, R.E. Family-based association analyses of imputed genotypes reveal genome-wide significant association of Alzheimer’s disease with OSBPL6, PTPRG, and PDCL3. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1608–1612.

- Hao, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, H. Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated Genes by Integration of GWAS Summary Data and Expression Data. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 653.

- Kunkle, B.W.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Sims, R.; Bis, J.C.; Damotte, V.; Naj, A.C.; Boland, A.; Vronskaya, M.; van der Lee, S.J.; Amlie-Wolf, A.; et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 414–430.

- Kunkle, B.W.; Schmidt, M.; Klein, H.U.; Naj, A.C.; Hamilton-Nelson, K.L.; Larson, E.B.; Evans, D.A.; De Jager, P.L.; Crane, P.K.; Buxbaum, J.D.; et al. Novel Alzheimer Disease Risk Loci and Pathways in African American Individuals Using the African Genome Resources Panel: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 102–113.

- Shigemizu, D.; Asanomi, Y.; Akiyama, S.; Mitsumori, R.; Niida, S.; Ozaki, K. Whole-genome sequencing reveals novel ethnicity-specific rare variants associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2554–2562.

- Yong, W.S.; Hsu, F.M.; Chen, P.Y. Profiling genome-wide DNA methylation. Epigenetics Chromatin 2016, 9, 26.

- Pathak, G.A.; Silzer, T.K.; Sun, J.; Zhou, Z.; Daniel, A.A.; Johnson, L.; O’Bryant, S.; Phillips, N.R.; Barber, R.C. Genome-Wide Methylation of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Mexican Americans Highlights Genes Involved in Synaptic Transport, Alzheimer’s Disease-Precursor Phenotypes, and Metabolic Morbidities. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 72, 733–749.

- Visscher, P.M.; Wray, N.R.; Zhang, Q.; Sklar, P.; McCarthy, M.I.; Brown, M.A.; Yang, J. 10 Years of GWAS Discovery: Biology, Function, and Translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 5–22.

- Sabarwal, A.; Kumar, K.; Singh, R.P. Hazardous effects of chemical pesticides on human health-Cancer and other associated disorders. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 63, 103–114.

- Gao, X.; Chen, Q.; Yao, H.; Tan, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, Z. Epigenetics in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 911635.

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bosse, Y.; Pare, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484.

- Wang, H.; Bennett, D.A.; De Jager, P.L.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhang, H.Y. Genome-wide epistasis analysis for Alzheimer’s disease and implications for genetic risk prediction. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 55.

- Vaz, M.; Silvestre, S. Alzheimer’s disease: Recent treatment strategies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 887, 173554.

- Panza, F.; Lozupone, M.; Seripa, D.; Imbimbo, B.P. Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for alzheimer disease: Is it now a long shot? Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 303–315.

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-disease-treatment (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Nehls, M. Unified theory of Alzheimer’s disease (UTAD): Implications for prevention and curative therapy. J. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 4, 3.

- Gauthier, S.; Alam, J.; Fillit, H.; Iwatsubo, T.; Liu-Seifert, H.; Sabbagh, M.; Salloway, S.; Sampaio, C.; Sims, J.R.; Sperling, B.; et al. Combination Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: Perspectives of the EU/US CTAD Task Force. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2019, 6, 164–168.

- Rosenberg, A.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T.; Solomon, A.; Kivipelto, M. Multidomain Interventions to Prevent Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Dementia: From FINGER to World-Wide FINGERS. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2020, 7, 29–36.

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 653–666.

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levalahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Backman, L.; Hanninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!