Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

NFIX, a member of the nuclear factor I (NFI) family of transcription factors, is known to be involved in muscle and central nervous system embryonic development. However, its expression in adults is limited. Similar to other developmental transcription factors, NFIX has been found to be altered in tumors, often promoting pro-tumorigenic functions, such as leading to proliferation, differentiation, and migration.

- NFIX

- cell

- cancer

1. Introduction

Tumorigenesis is characterized by the gain of malignant properties, including sustained proliferative signaling, phenotypic plasticity, and epigenetic reprogramming, all features also observed during embryonic development [1]. Not surprisingly, several pathways that play central roles during development are also altered during tumorigenesis. This is the case of RhoA/ROCK and JUNB signaling pathways that regulate nuclear factor I X (NFIX) expression during myogenesis and are involved in cancer cell proliferation and invasion [2][3]. In prostate cancer cells, SOX4, a transcription factor involved in the development of various tissues and which is commonly overexpressed in tumors [4], is overexpressed and activates NFIX [5]. Moreover, the overexpression of acyl-CoA synthetase 4 in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line leads to changes in various developmental pathways, including the overactivation of NFIX and its target gene ENO3 [6].

Apart from its positive and negative transcriptional regulation, genomic analysis of the NFIX gene in various tumors has revealed several mutations, including gene fusions [7]. Gene fusions are chromosomal rearrangements, usually involving insertions, deletions, inversions, or translocations, where two independent genes fuse together to form a hybrid gene [8]. These fusions have been studied primarily in the context of hematological and mesenchymal malignancies, but they also contribute to epithelial tumors [8]. Even though the role of NFIX in gene fusions is still not fully understood, it is likely that most of the gene fusions involving this gene have oncogenic properties (Table 1). This is the case of NFIX-MAST1 [9] fusions in breast cancer and may also include the NFIX–PKN1 translocation, described in carcinoma of the skin [10], the BSG-NFIX fusion identified in breast cancer [11] and the NFIX–STAT6 gene fusion, which was identified in a tumor lesion with histological features of a solitary fibrous tumor [7].

Table 1. Oncogenic and tumor suppressor roles of NFIX

| Putative Oncogenic Gene Fusions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of cancer | Mechanism | References |

| Breast | NFIX-MAST1 promotes proliferation. | [9] |

| BSG-NFIX fusion present in low copy number and with unknown function. | [11] | |

| Skin | NFIX–PKN1 fusion with unknown function. | [10] |

| Sarcoma | NFIX–STAT6 fusion with unknown function. | [7] |

| Oncogene | ||

| Type of cancer | Mechanism | References |

| Pancreas | ceRNA network: MAFG-AS1 binds to miR-3196 leading to NFIX expression. | [12] |

| Lung | ceRNA network: SNHG3 binds to miR-1343-3p leading to NFIX expression. | [13] |

| NFIX regulates genes involved in proliferation, migration, and invasion (IL6ST, TIMP1 and ITGB1). | [14] | |

| Brain | NFIX upregulates ezrin (EZR) promoting cell migration. | [15] |

| Prostate | NFIX binds to FOXA1 regulating prostate-specific gene expression. | [16] |

| Putative Tumor Suppressor | ||

| Type of cancer | Mechanism | References |

| Esophageal | miR-1290 binds to NFIX, decreasing its expression. | [17] |

| Colorectal | miR-647 and miR-1914 co-target NFIX, decreasing its expression. | [18] |

| Ovarian | miR-744 reduces NFIX expression, leading to apoptosis. | [19] |

To understand the role of NFIX in cancer, it is essential to know how the gene fusions, epigenetic changes, non-coding RNAs targets, and mutations in NFIX and in its regulatory elements contribute to specific pathways that drive tumor progression. This can reveal when NFIX acts as an oncogene and when it acts as a tumor suppressor (Table 1).

2. Nuclear Factor I X and Oxidative Stress

Tumors are characterized by increased levels of oxidative stress, which impact tumorigenesis in different ways, including by (i) triggering DNA damage; (ii) altering signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and tumor growth; (iii) leading to chronic inflammation in the tumor environment; and (iv) changing the composition of the extracellular matrix, which impacts cell survival, proliferation, migration, and adhesion [20][21][22][23][24].

Members of the NFI family are thought to be pro-oxidants, and their inactivation is crucial for proper oxidative stress response [25]. NFIX may act as an oxidative stress producer, for example, by activating the transcription of CYP1A1 (encoding cytochrome P450 1A1), which has an NFI binding site in the promoter region [26]. CYP1A1 is known to be pro-carcinogenic [27] and, similarly to other monooxygenases, leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as part of its catalytic activity [28][29]. Under normal conditions, the expression of CYP1A1 is suppressed, possibly due to an autoregulatory loop that controls the expression of CYP1A1 via CYP1A1-based hydrogen peroxide production and the NFI family [28][30]. However, when deregulated, the increased production of ROS and the production of pro-oncogenic metabolites may contribute to tumor progression [27]. Studies have shown that CYP1A1 is upregulated in breast [30], bladder [31], and colon cancers [31]. Accordingly, the knockdown of CYP1A1 has been found to downregulate ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways and to induce the AMPK pathway, leading to a reduction in tumor progression and cancer cell survival [30]. Supporting the idea that oxidative stress impacts the function of NFI family members, hepatoma cell lines treated with the pro-oxidant hydrogen peroxide or L-buthionine- (S,R)-sulfoximine showed impaired NFI binding to its DNA binding site due to increased oxidative stress, resulting in the inhibition of its function as a transcription factor [26].

Analysis of oxidative stress-related differentially expressed genes using data from 594 lung adenocarcinoma patients revealed that NFIX is downregulated in this type of cancer and has a direct correlation with poor prognosis [32]. This research proposed that NFIX downregulation serves as a mechanism for cancer cells to reduce ROS production, thus, increasing their fitness [32]. Similarly, another study found that NFIX upregulation is associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer because of its role in ROS status [33]. This indicates that NFIX may be used as a key gene in a ROS scoring system to predict prognosis and therapeutic efficiency. NFIX has also been identified as part of the common mitochondrial defect signature genes in hepatocellular carcinoma, which are genes activated in response to mitochondrial dysfunction, a major source of ROS in organisms [34], and associated with poor prognosis and reduced overall survival [35].

Besides NFIX protein being associated with oxidative stress in different contexts, circNFIX has also been shown to have an impact on both tumor progression and oxidative stress [36][37][38]. For example, circNFIX was found to promote cancer progression by upregulating glycolysis, as well as glucose uptake in glioma [39] and in non-small cell lung cancer [40], which can lead to overproduction of ROS in the context of diabetes [41]. In glioma, tumor progression was associated with the suppression of miR-378e and consequent expression of ribophorin-II (RPN2) [39], a target of miR-378e that promotes increased ROS and glycolysis [39][42]. Similarly, in non-small cell lung cancer, tumor progression was associated with the suppression of miR-212-3p and upregulation of ADAM10 [40], a protein that has been shown to be involved in oxidative stress-related conditions, such as cancer, Alzheimer, neurodegeneration, and inflammation [43]. Further research is needed in order to understand whether NFIX’s role as a pro-oxidant contributes to ROS accumulation in tumors and therefore promotes genomic instability, increased proliferation, and differentiation. In support of this notion, studies are recognizing NFIX and its target genes/proteins that are involved in oxidative stress as potential therapeutic targets for cancer therapy [30][32][33][39].

3. Nuclear Factor I X and Cell Fate

Given the pleiotropic role of NFIX during development, it is not surprising that changes in NFIX expression can significantly influence proliferation and differentiation. Apart from NFIX’s indirect role in proliferation through its involvement in oxidative stress, NFIX has also been shown to be involved in cell cycle regulation and cell fate decisions, which are closely linked to proliferation. For example, NFIX downregulation has been shown to reduce proliferation and cell viability in lung cancer [14] but to lead to increased proliferation in the context of endometrial carcinoma [44] and colorectal cancer [18]. On the other hand, overexpression of NFIX in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma has been shown to reduce cell proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest in G1/G0 phase [17].

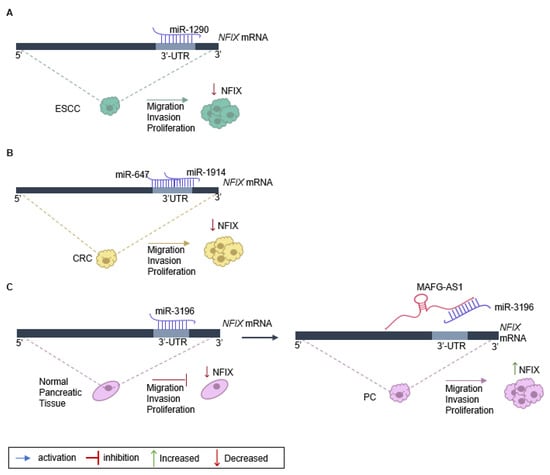

The role of NFIX in cancer proliferation, migration, and invasion has been linked to the expression of non-coding RNAs, namely miRNA and lncRNA (Table 1). One example is the regulation of NFIX mediated by miR-1290, which has a target site on the NFIX 3′-UTR [17] (Figure 1A). An inverse correlation between the levels of miR-1290 and NFIX protein and mRNA was observed in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma tissue samples, suggesting that miR-1290 is an oncogene that downregulates NFIX and promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion in this type of tumor [17]. Moreover, analysis of the genetic profile of colorectal cancer tissue through screening of genes that were upregulated or downregulated identified increased expression of two miRNAs, miR-1914 and miR-647, in colorectal cancer specimens and cell lines [18]. These miRNAs were shown to promote the proliferation and migration of colorectal cancer cells, functioning as oncogenes, possibly by directly targeting and downregulating NFIX (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Regulation of NFIX expression in cancer. (A) NFIX regulation by miR-1290 promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) progression: miR-1290 directly targets the 3′UTR sites of NFIX mRNA, negatively regulating its expression. The decrease in NFIX expression leads to ESCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. (B) NFIX co-regulation by miR-647 and miR-1914 in colorectal cancer (CRC): NFIX mRNA is co-targeted by miR-647 and miR-1914 in the 3′UTR. The negative regulation of NFIX expression leads to CRC cell migration and invasion. (C) ceRNA network of MAFG-AS1/miR-3196/NFIX in pancreatic cancer (PC): in normal pancreatic tissue, miR-3196 directly binds to 3′UTR sites of NFIX mRNA and silences its expression. The lncRNA MAFG-AS1, highly expressed in PC cells, binds directly to the miR-3196, promoting NFIX upregulation and, as a consequence leading to proliferation, migration, and invasion of PC cells.

The impact of NFIX on proliferation has also been associated with lncRNAs that play diverse roles in regulating gene expression [45]. Numerous lncRNAs can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) to regulate the expression of coding genes that have common miRNA response elements [46], with pancreatic cancer being one example. In normal pancreatic tissue, miRNA-3196 is expressed, leading to a downregulation of NFIX [12]. However, in pancreatic cancer tissue, the lncRNA MAFG-AS1 acts as a ceRNA and binds to the miR-3196, resulting in the neutralization of miR-3196 and the upregulation of NFIX [12]. Functional assays have shown that MAFG-AS1 knockdown suppresses cell proliferation and migration while promoting cell apoptosis in pancreatic cancer [12]. Additionally, when miR-3196 is up-regulated, the proliferative and migratory capacities of pancreatic cancer cells are inhibited (Figure 1C).

In addition to cell cycle regulation and cell proliferation, NFIX may also play a role in other cell fates. Apoptosis is a central pathway that is rendered inactive in cancer cells [19][47][48]. It was recently shown that NFIX overactivation has an anti-apoptotic effect via the STAT5 signaling pathway leading to a reduction in apoptosis levels in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [47]. This is supported by the observation that the overactivation of NFIX leads to increased expression of the anti-apoptotic factor Bcl2l1 (encoding BCL-XL) in these cells [47]. Additionally, NFIX downregulation through overexpression of miR-744-5p in ovarian cancer has been shown to decrease the expression of BCL2, an anti-apoptotic factor, leading to an increase in apoptosis levels [19]. Moreover, hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells that lack NFIX cannot survive in the bone marrow after transplantation due to an increase in apoptosis [49]. Nevertheless, NFIX silencing in the context of human spermatogonia stem cells seems to suppress early apoptosis [50], suggesting that its role in apoptosis may be tissue and/or cell-type-dependent.

Considering the important role of the NFI family in neuronal development, several studies have analyzed NFIX’s role in glioblastomas as a potential tumor-promoter [15][49][51]. One such study found that NFIX promotes glioblastoma cell migration by directly upregulating the expression of EZR (encoding ezrin), which is involved in linking the actin cytoskeleton and the plasma membrane and plays a role in cell migration [15] (Table 1). In accordance with the role of NFIX promoting cell migration, NFIX has been identified as a potential oncogene that plays a role in the development of metastasis. NFIX was recently described as a master regulator activating the expression of 17 genes that are involved in migration and invasion in lung cancer [14]. Using two different cell lines for lung cancer, it was shown that NFIX regulates interleukin-6 receptor subunit β (IL6ST), metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 (TIMP1), and integrin β-1 (ITGB1) genes, all of which are involved in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [14] (Table 1). Altogether these studies suggest that NFIX may be a key player during cancer onset and progression, modulating several pathways implicated in tumorigenesis.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms24054293

References

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: New dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46.

- Yuan, B.; Cui, J.; Wang, W.; Deng, K. Gα12/13 signaling promotes cervical cancer invasion through the RhoA/ROCK-JNK signaling axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 473, 1240–1246.

- Pei, H.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Hu, W.; Nie, J.; Mao, W.; et al. RAC2 promotes abnormal proliferation of quiescent cells by enhanced JUNB expression via the MAL-SRF pathway. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 1115–1123.

- Moreno, C.S. SOX4: The unappreciated oncogene. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 67, 57–64.

- Scharer, C.D.; McCabe, C.D.; Ali-Seyed, M.; Berger, M.F.; Bulyk, M.L.; Moreno, C.S. Genome-wide promoter analysis of the SOX4 transcriptional network in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 709–717.

- Castillo, A.F.; Orlando, U.D.; López, P.; Solano, A.R.; Maloberti, P.M.; Podesta, E.J. Gene expression profile and signaling pathways in MCF-7 breast cancer cells mediated by acyl-coa synthetase 4 overexpression. Transcr. Open Access 2015, 3, 1–9.

- Moura, D.; Díaz-Martín, J.; Bagué, S.; Orellana-Fernandez, R.; Sebio, A.; Mondaza-Hernandez, J.; Salguero-Aranda, C.; Rojo, F.; Hindi, N.; Fletcher, C.; et al. A novel NFIX-STAT6 gene fusion in solitary fibrous tumor: A case report. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7514.

- Prensner, J.R.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. Oncogenic gene fusions in epithelial carcinomas. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009, 19, 82–91.

- Robinson, D.R.; Kalyana-Sundaram, S.; Wu, Y.-M.; Shankar, S.; Cao, X.; Ateeq, B.; Asangani, I.; Iyer, M.; Maher, C.A.; Grasso, C.S.; et al. Functionally recurrent rearrangements of the MAST kinase and Notch gene families in breast cancer. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1646–1651.

- Kastnerova, L.; Luzar, B.; Goto, K.; Grishakov, V.; Gatalica, Z.; Kamarachev, J.; Martinek, P.; Hájková, V.; Grossmann, P.; Imai, H.; et al. Secretory carcinoma of the skin. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1092–1098.

- Edgren, H.; Murumagi, A.; Kangaspeska, S.; Nicorici, D.; Hongisto, V.; Kleivi, K.; Rye, I.H.; Nyberg, S.; Wolf, M.; Borresen-Dale, A.-L.; et al. Identification of fusion genes in breast cancer by paired-end RNA-sequencing. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R6.

- Ye, L.; Feng, W.; Weng, H.; Yuan, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. MAFG-AS1 aggravates the progression of pancreatic cancer by sponging miR-3196 to boost NFIX. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 591.

- Zhao, L.; Song, X.; Guo, Y.; Ding, N.; Wang, T.; Huang, L. Long non-coding RNA SNHG3 promotes the development of non-small cell lung cancer via the miR-1343-3p/NFIX pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 48, 1–12.

- Rahman, N.I.; Abdul Murad, N.A.; Mollah, M.M.; Jamal, R.; Harun, R. NFIX as a master regulator for lung cancer progression. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 540.

- Liu, Z.; Ge, R.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Cheng, K.K.-Y.; Tao, J.; Wu, D.; Mao, J. Nuclear factor IX promotes glioblastoma development through transcriptional activation of Ezrin. Oncogenesis 2020, 9, 39.

- Grabowska, M.M.; Elliott, A.D.; DeGraff, D.J.; Anderson, P.D.; Anumanthan, G.; Yamashita, H.; Sun, Q.; Friedman, D.B.; Hachey, D.L.; Yu, X.; et al. NFI transcription factors interact with FOXA1 to regulate prostate-specific gene expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 949–964.

- Mao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, B. MiR-1290 promotes cancer progression by targeting nuclear factor I/X(NFIX) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 76, 82–93.

- Liu, S.; Qu, D.; Li, W.; He, C.; Li, S.; Wu, G.; Zhao, Q.; Shen, L.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J. miR-647 and miR-1914 promote cancer progression equivalently by downregulating nuclear factor IX in colorectal cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 8189–8199.

- Kleemann, M.; Schneider, H.; Unger, K.; Sander, P.; Schneider, E.M.; Fischer-Posovszky, P.; Handrick, R.; Otte, K. MiR-744-5p inducing cell death by directly targeting HNRNPC and NFIX in ovarian cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9020.

- Martins, S.G.; Zilhão, R.; Thorsteinsdóttir, S.; Carlos, A.R. Linking Oxidative stress and DNA Damage to changes in the expression of extracellular matrix components. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 1279.

- Reuter, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Chaturvedi, M.M.; Aggarwal, B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1603–1616.

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Tew, K.D. Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167–197.

- Freudenthal, B.D.; Whitaker, A.M.; Schaich, M.A.; Smith, M.S.; Flynn, T.S. Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage from mechanism to disease. Front. Biosci. 2017, 22, 1493–1522.

- Sosa, V.; Moliné, T.; Somoza, R.; Paciucci, R.; Kondoh, H.; Lleonart, M.E. Oxidative stress and cancer: An overview. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 376–390.

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Gronostajski, R.M. Identification of a conserved oxidation-sensitive cysteine residue in the NFI family of DNA-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 29949–29955.

- Morel, Y.; Barouki, R. Down-regulation of cytochrome P450 1A1 gene promoter by oxidative stress. Critical contribution of nuclear factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 26969–26976.

- Androutsopoulos, V.P.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Spandidos, D.A. Cytochrome P450 CYP1A1: Wider roles in cancer progression and prevention. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 187.

- Morel, Y.; Mermod, N.; Barouki, R. An autoregulatory loop controlling CYP1A1 gene expression: Role of H2O2 and NFI. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 6825–6832.

- Taverne, Y.J.; Merkus, D.; Bogers, A.J.; Halliwell, B.; Duncker, D.J.; Lyons, T.W. Reactive oxygen species: Radical factors in the evolution of animal life. Bioessays 2018, 40, 1700158.

- Rodriguez, M.; Potter, D.A. CYP1A1 regulates breast cancer proliferation and survival. Mol. Cancer Res. 2013, 11, 780–792.

- Androutsopoulos, V.P.; Spyrou, I.; Ploumidis, A.; Papalampros, A.E.; Kyriakakis, M.; Delakas, D.; Spandidos, D.A.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Expression profile of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 enzymes in colon and bladder tumors. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82487.

- Guo, Q.; Liu, X.-L.; Liu, H.-S.; Luo, X.-Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ji, Y.-M.; Liu, T.; Guo, J.-L.; Zhang, J. The risk model based on the three oxidative stress-related genes evaluates the prognosis of LAC patients. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 4022896.

- Sun, C.; Guo, E.; Zhou, B.; Shan, W.; Huang, J.; Weng, D.; Wu, P.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; et al. A reactive oxygen species scoring system predicts cisplatin sensitivity and prognosis in ovarian cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1061.

- Bhatti, J.S.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in metabolic disorders—A step towards mitochondria based therapeutic strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1066–1077.

- Lee, Y.; Jee, B.A.; Kwon, S.M.; Yoon, Y.; Xu, W.G.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.W.; Thorgeirsson, S.S.; Lee, J.; Woo, H.G.; et al. Identification of a mitochondrial defect gene signature reveals NUPR1 as a key regulator of liver cancer progression. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1174–1189.

- Cui, X.; Dong, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Yang, W.; Liu, G.; Sun, S.; Xu, W. A circular RNA from NFIX facilitates oxidative stress-induced H9c2 cells apoptosis. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2020, 56, 715–722.

- Patop, I.L.; Kadener, S. circRNAs in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2018, 48, 121–127.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, Q.; Tang, X.; Shen, J.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Li, X.; et al. Circular RNAs in the regulation of oxidative stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 1906.

- Ding, C.; Wu, Z.; You, H.; Ge, H.; Zheng, S.; Lin, Y.; Wu, X.; Lin, Z.; Kang, D. CircNFIX promotes progression of glioma through regulating miR-378e/RPN2 axis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 506.

- Lu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Y. CircNFIX Acts as a miR-212-3p sponge to enhance the malignant progression of non-small cell lung cancer by up-regulating ADAM10. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 9577–9587.

- Yaribeygi, H.; Atkin, S.L.; Sahebkar, A. A review of the molecular mechanisms of hyperglycemia-induced free radical generation leading to oxidative stress. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 1300–1312.

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Ke, Z.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liao, Z. Ribophorin II promotes the epithelial–mesenchymal transition and aerobic glycolysis of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma via regulating reactive oxygen species-mediated Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B activation. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 5141–5151.

- Crawford, H.; Dempsey, P.; Brown, G.; Adam, L.; Moss, M. ADAM10 as a therapeutic target for cancer and inflammation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 2288–2299.

- Yang, L.; Yang, Z.; Yao, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, G. miR-210 promotes progression of endometrial carcinoma by regulating the expression of NFIX. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 5213–5222.

- Jiang, M.-C.; Ni, J.-J.; Cui, W.-Y.; Wang, B.-Y.; Zhuo, W. Emerging roles of lncRNA in cancer and therapeutic opportunities. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 1354–1366.

- Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Xu, M.; Yan, Y.; Huang, L.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Zheng, W.; Liu, H.; et al. A 15-lncRNA signature predicts survival and functions as a ceRNA in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 5799.

- Hall, T.; Walker, M.; Ganuza, M.; Holmfeldt, P.; Bordas, M.; Kang, G.; Bi, W.; Palmer, L.E.; Finkelstein, D.; McKinney-Freeman, S. Nfix promotes survival of immature hematopoietic cells via regulation of C-MPL. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 943–950.

- Holmfeldt, P.; Pardieck, J.; Saulsberry, A.C.; Nandakumar, S.K.; Finkelstein, D.; Gray, J.T.; Persons, D.A.; McKinney-Freeman, S. Nfix is a novel regulator of murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell survival. Blood 2013, 122, 2987–2996.

- Ahmed, S.P.; Castresana, J.S.; Shahi, M.H. Role of circular RNA in brain tumor development. Cells 2022, 11, 2130.

- Zhou, F.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Niu, M.; Fu, H.; Qiu, Q.; Mao, G.; Wang, H.; Wen, L.; Wang, H.; et al. MiR-663a Stimulates proliferation and suppresses early apoptosis of human spermatogonial stem cells by targeting NFIX and regulating cell cycle. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2018, 12, 319–336.

- Ge, R.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z. A novel tumor-promoting role for nuclear factor IX in glioblastoma is mediated through transcriptional activation of GINS1. Mol. Cancer Res. 2022, 2022, OF1–OF10.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!