You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Education & Educational Research

Teachers’ engagement with their own multilingualism in a pre-service teacher education context. As linguistic diversity in society and schools around the globe is increasing, teachers are required to meet the challenges of teaching children who live with multiple languages. Teachers are seldom required to reflect on and engage with their own multilingualism, which forms the basis of a subjective and experiential approach to educating teachers multilingually.

- multilingualism

- DLC (dominant language constellation)

- language repertoires

1. Multilingualism in Education

Multilingualism is neither an exception nor a new phenomenon. Edwards (1994, p. 1) described it as ‘a normal and unremarkable necessity’ for individuals and societies. More recently, Aronin and Singleton (2008, 2012) and Aronin (2019a, pp. 26–27) have called for ‘a new linguistic dispensation’ based on ‘an unparalleled spread of the use of English as an international language [and] a remarkable diversification of the languages in use’, where flexible language practices include ‘monolingual, bilingual, and multilingual arrangements’. This increase in linguistic diversity is evident in the Norwegian context, which has been described by Lanza (2020, p. 131) as a ‘linguistic paradise’ as a result of a certain tolerance of linguistic diversity that is evident in policy, curriculum renewal processes, and attitudes towards multilingualism. Not only have Norwegian schools become more culturally and linguistically diverse because of immigration to the country and an increase in the number of children born in Norway to immigrant parents (18.5% according to Statistics Norway 2021), but Norwegian society has recently become more open to accommodating a mosaic of languages. The indigenous languages Sami, Kven, Romani, and Romanes have official status as national minority languages, as does Norwegian Sign Language; there are two written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål and Nynorsk, and a multitude of spoken dialects across the country (Vikøy and Haukås 2021).

Globally, national curricula are increasingly integrating references to linguistic diversity, as exemplified by two northern European countries. The Finnish and Norwegian curricula both refer explicitly to linguistic diversity, and the term ‘multilingual’ or ‘multilingualism’ appears in both. The Finnish National Agency for Education emphasises an ‘Awareness of languages in general and appreciation of multilingualism and multiculturalism’ (Finnish National Agency for Education 2014; Kalaja and Pitkänen-Huhta 2020, p. 6), while the Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training (2020), English curriculum (Læreplan i engelsk) states, ‘Pupils should be given a basis for seeing their own and the identity of others in a multilingual and multicultural context’ (p. 3). However, Kalaja and Pitkänen-Huhta (2020, p. 7), when analysing the Finnish curriculum, lament the fact that references to multilingualism remain ‘at the level of buzzwords and lack any concrete applications’, as curricula do not come with how-to manuals. Although references to multilingualism and linguistic diversity are much-needed and welcome additions to national curricula and educational policy, there is a scarcity of concrete guidelines for teacher training with elements of plurilingual pedagogy (Otwinowska 2014, p. 307).

Several studies in Norway have highlighted the positive attitudes of teachers towards the phenomenon of multilingualism (Haukås 2016). However, there is little evidence of teachers integrating plurilingual practices in their teaching. For example, Pran and Holst (2015) revealed that only three out of ten teachers in Grades 1–10 have at some point carried out activities on the topic of multilingualism with their classes. A survey carried out among 176 teachers of English showed that only 5% believed they were very well qualified to teach in multilingual classrooms (Krulatz and Dahl 2016). Despite a high level of qualifications and well-intentioned attitudes towards multilingualism and L1 activation, the teachers in Burner and Carlsen’s (2019) study, working in a school for newly arrived students, struggled to implement multilingual teaching practices. Instead, they prioritised the learning of Norwegian over the L3 (English) for integration purposes, even though English is a compulsory subject in the Norwegian curriculum. Similarly, the teachers in a longitudinal study by Lorenz et al. (2021) supported the idea of integrating multilingual practices, but they did not implement such practices systematically. Hence, recent research into teachers’ perceptions and practices in Norway has confirmed that there is still a need to educate teachers who understand and can knowledgeably use multiple languages and multilingual teaching practices in their classrooms in general and in the English classroom in particular.

In calling for a greater focus on multilingualism and plurilingual practices in teacher education, researchers and educators in different contexts have also been considering what teachers need to learn about the phenomenon. Firstly, as no one language fulfils an individual’s full communicative, cognitive, or emotional requirements, it is imperative for teachers to understand multilingualism as a complex, dynamic, shifting, and multidimensional phenomenon (Ibrahim 2022; Jessner 2013; Cenoz and Gorter 2011, 2015). According to Otwinowska (2014, 2017), teachers should develop an awareness of crosslinguistic, metalinguistic, and psycholinguistic knowledge concerning multiple language acquisition. García and Kleyn’s (2019) three-strand approach includes knowledge of the children and their families, knowledge of bi/multilingualism, and knowledge of appropriate plurilingual pedagogies. However, not only do individuals seldom identify as multilingual as a result of monolingualizing processes that have penetrated and structured education systems and ideologies, but they are rarely encouraged to explore their personal engagement with multilingualism. A focus on multilingual practices in teacher education can contribute to positive attitudes towards multilingualism (Portolés and Martí 2020; Haukås 2016), but identity-based approaches, where teachers actively go through a process of identification as multilingual, are also proving to be effective (Krulatz and Xu 2021). Ibrahim (forthcoming) argues that teachers need to develop an understanding of multilingualism as subjectively lived or experienced, ‘involving positive and negative emotions, attitudes, beliefs, visions and identities’ (Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer 2019, p. 1). This personal and subjective approach constitutes key first steps in ‘raising the critical awareness amongst teachers and teacher trainers of their own multilingual background, their own learning trajectories and their own attitudes toward plurilingualism and plurilingual practices’ (Wei 2020, p. 274).

2. Arts-Based Approaches in Teacher Education

Even though researchers have employed a variety of traditional tools, such as interviews, narratives, and discourse analysis, there has been a strong ‘lingualism’ (Block 2014) bias in investigating the multilingual phenomenon. The more recent focus on visual and multimodal/artefactual methods affords research into teacher education and multilingualism interesting new avenues. Whitelaw (2019, p. 7), developing the concept of critical aesthetic practice, foregrounds the role of the arts in developing an awareness and understanding through sensory experiences that allow for thinking, seeing, feeling, and perceiving differently. Arts-based practices open up a safe, creative space for engaging with linguistic repertoires and exploring teachers’ and students’ identity connections with their linguistic histories and biographies (Busch 2018; Blommaert and Backus 2013; Barkhuizen and Strauss 2020). They bring to the classroom different ways of being, which disrupt the verbocentric status quo (Kendrick and McKay 2002, 2009) and provide a transformative lens through which to re-envision language education. Arts-based approaches personalise the learning process and provide more opportunities for inclusive practices, as they allow for a ‘certain freedom and spontaneity’ (Lähteelä et al. 2021, p. 21) in appropriating the tools for self-expression related to experience, action, and emotion.

Researchers and practitioners have been engaging with the visual turn in teacher education in innovative ways. Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer (2019) gathered thirteen studies using a variety of visual methods (drawings, photos, objects, artefacts) across different contexts, including teacher education. For example, the four case studies in Part 3: Multilingual Teacher Education (pp. 197–274) used drawings to explore the participants’ future selves as teachers of English in linguistically diverse contexts. Even though these studies did not engage directly with the teachers’ perceptions of themselves as multilingual individuals, Pinto (2019, p. 229) did highlight the ‘discovery of their own ‘plurilinguality’, or their ability to think, be(come), and act plurilingually as teachers of EFL. Hirsu et al. (2021) described a project in which researchers, teachers, and artists worked together to operationalise translingual practices in the classroom by side-lining the complex definition of translanguaging. They adopted a creative arts-based approach, in which students used their full range of semiotic resources, highlighting the ‘creative and critical dimension’ (Wei 2018, p. 13) of multilingualism. Teachers’ conversations around those visuals, both individually and collaboratively, also proved to be meaningful in deepening discussions around teacher identity construction (Orland-Barak and Maskit 2017, p. 28).

Aronin and Ó Laoire (2013, p. 225) call for a greater focus on ‘the material culture of multilingualism’ and argue that ‘a deliberate focus on the study of materialities (artefacts, objects, and spaces) can contribute significantly to the investigation of multilingualism’. Ibrahim (2019, 2021) combined visual and artefactual elements in exploring children’s identity, where the multimodal text goes beyond the ‘predominantly verbal’ and ‘accommodates the interplay of different semiotic modes and recognises the complexity of multimodal narrative meaning’ (Page 2010, p. 115). Using drawings and selected objects to represent their languages, children described multiple and erratic language trajectories, where repertoires become ‘biographically organised complexes of resources [that] follow the rhythms of human lives’ (Blommaert and Backus 2011, p. 9). Barkhuizen et al. (2014) privileged the term multimodal narratives (such as drawings, photographs, videos, digital stories, etc.) to highlight the multidimensionality of this representation resource. In this study, student teachers created a concrete visual artefact of their language repertoires and DLCs, constituting a ‘powerful tool for delving into participants’ feelings, attitudes and perceptions about the self’ (Ibrahim 2019, p. 48). The current study heeds the call for pedagogical applications of DLC research by embedding DLCs in artefactual, multimodal practices in researching teacher education.

3. Dominant Language Constellations (DLCs) as a Research and Pedagogical Approach

The concept of the DLC (Aronin 2006, 2016; Lo Bianco and Aronin 2020; Aronin and Vetter 2021) was developed in an attempt to capture the complexity, multidimensionality, and unpredictability of contemporary multilingual communication. The DLC bridges the hypothetical monolingual perspective, where individuals only need one language to function on a daily basis, and the multilingual perspective, where a full language repertoire consists of a ‘long list of skills in many languages accumulated with the help of mobility, new media and technologies’ (Aronin 2019b, p. 20). Aronin (2019b, p. 21) defines an individual’s DLC as ‘the group of a person’s most expedient languages, functioning as an entire unit and enabling an individual to meet all his/her needs in a multilingual environment’. While a language repertoire refers to ‘the totality of linguistic skills in all the languages possessed by an individual or by a community and may include several languages, a Dominant Language Constellation captures only a subset of them (typically but not always three languages) that are deemed to be of prime importance’ (Aronin and Moccozet 2021, p. 2). However, as argued by Coetzee-Van Rooy (2018), ‘a single dominant language constellation’ (p. 25) is unrealistic in certain contexts, and the division between language repertoires and DLCs may be more porous than first identified. Hence, it makes more sense to consider the ‘co-existence of several ‘dominant language constellations’ in the “language repertoires” of people’ (p. 24), where the apparently lesser-used languages in a repertoire gain importance, visibility, and functionality in different domains; for example, different languages contribute to a family DLC, a professional DLC, or a leisure DLC. This highlights the nature of DLCs as unstable, evolving, and fluctuating as a result of political changes, group and individual migration, and new life circumstances (Krulatz and Dahl 2021).

Even though the DLC emerged as a theoretical concept, it is now being operationalised in various contexts. For example, Nightingale’s (2020) study focused on an individual’s language use and ‘how his most expedient languages are reconfigured according to the multilingual environment and how they relate to his emotions, language attitudes, and identity construct’ (2020, p. 232). This study captured not only the functional aspects of the individual’s DLC but also his affective and emotional ties to the various languages.

More recently, the concept of the DLC has been employed in education and teacher training. Coetzee-Van Rooy (2018) investigated the DLCs of urban South African youth to create and contribute to more effective multilingual language-in-education policies and practices. Björklund and Björklund (2021) used individual and institutional DLCs within the teaching practicum as part of the teacher education programmes at Åbo Akademi University in Finland as a tool to uncover the multiple layers of DLCs in organizations. Krulatz and Dahl (2021) and Vetter (2021) both took a language policy perspective: the former compared ‘the actual and imagined DLCs of refugees to Norway with the majority communal DLC in Norway and the imagined DLCs that are envisioned for refugees by the government, educational institutions, and communities of settlement’ (p. 115), while the latter analysed school language education policy in urban secondary schools. Yoel (2021) investigated the evolution of the DLCs of immigrant (Russian) teacher trainees of English in Israel. Although they used English as a ‘pivot language’ (p. 158) that allowed them to negotiate initial access to Israeli society, the objective was to learn Hebrew in order to integrate. As a result, their individual and community DLCs underwent a process of transition and reconfiguration, as Hebrew occupied a more prominent position and English became their professional language.

4. DLC Maps and Modelling: Visual and Concrete Representations of Subjectively Lived Multilingualism

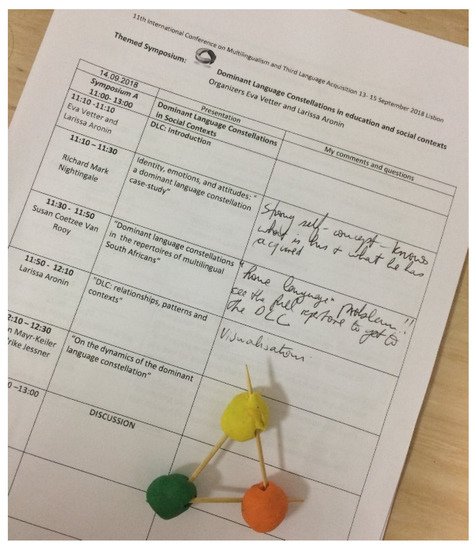

The original visual representation of DLC maps reflected a constellation in the night sky, with stars representing the different languages (Aronin 2019b; Lo Bianco and Aronin 2020; Aronin and Vetter 2021). At the XIth International Conference on Third Language Acquisition and Multilingualism in Lisbon (Aronin 2018), the author of this article discovered 3D DLC modelling with plasticine and sticks (Figure 1), an activity that provided physical, tactile, and creative engagement with her DLC. As Aronin and Moccozet (2021) stated, external concrete representations ‘boost cognition by shortcutting analytic processes, saving internal memory, creating persistent referents and providing structures that can serve as a shareable object of thought’ (pp. 5–6). Hence, a ‘3D plasticine model of a personal DLC serves as both a cognitive extension and a material symbol of one’s own sociolinguistic existence and the language skills that ensure this existence’ (Aronin and Moccozet 2021, p. 7). This approach to exploring DLCs affords individuals deeper, more personal connections with their language repertoires and DLCs, thus enhancing self-awareness of multilingualism as a concept and of themselves as multilingual individuals. The plasticine models, in different colours and sizes, uncover the relationships, map the journeys, and reveal the identities that individuals ascribe to their languages.

Figure 1. Author’s DLC model created at the XIth International Conference on Third Language Acquisition Multilingualism in Lisbon (Aronin 2018) and reproduced in Aronin (2021).

Visualization methods, such as DLC maps, plasticine models, and computer-assisted modelling (Aronin and Moccozet 2021), offer teacher educators a promising tool for exploring student teachers’ relationships with their languages and their individual perceptions of the role of these languages in their lives, and for reflecting on the impact this may have on their future practice.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/languages7020152

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!