Cancer is responsible for lifelong disability and decreased quality of life. Cancer cells undergo numerous changes in their metabolic pathways, involving energy and biosynthetic processes, so that they can proliferate. Hence, the metabolic pathways appear as interesting targets for a broad spectrum of therapeutic approaches. Mushrooms possess biological activities relevant to disease-fighting and to the prevention of cancer. They have a long-standing tradition of use in ethnomedicine and have been included as an adjunct therapy during and after oncological care. Mushroom-derived compounds have also been reported to target the key signature of cancer cells in in vitro and in vivo studies.

- cancer

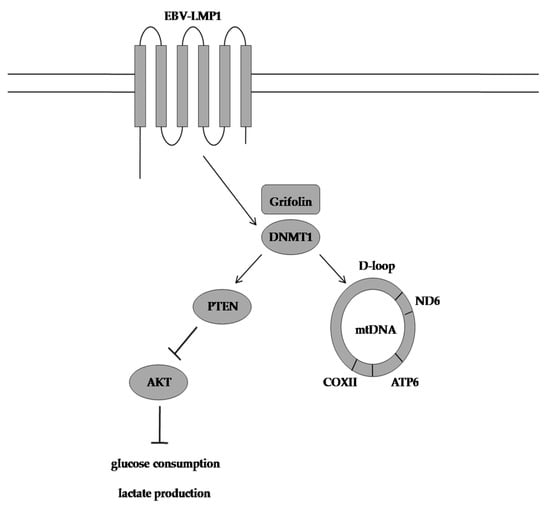

- conjugated linoleic acid

- GL22

- grifolin

- metabolic reprogramming

- neoalbaconol

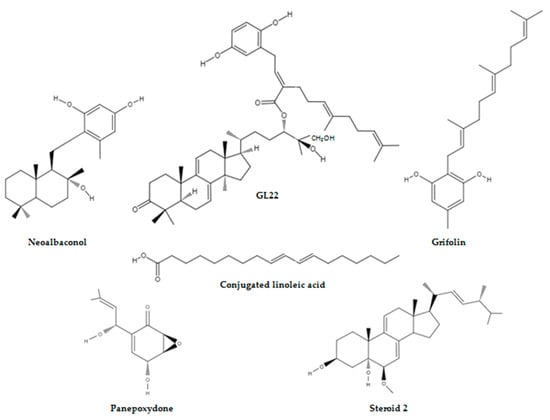

1. Neoalbaconol Induced Energy Depletion and Multiple Types of Cell Death by Targeting Phosphoinositide-Dependent Kinase 1-Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B Signalling Pathway

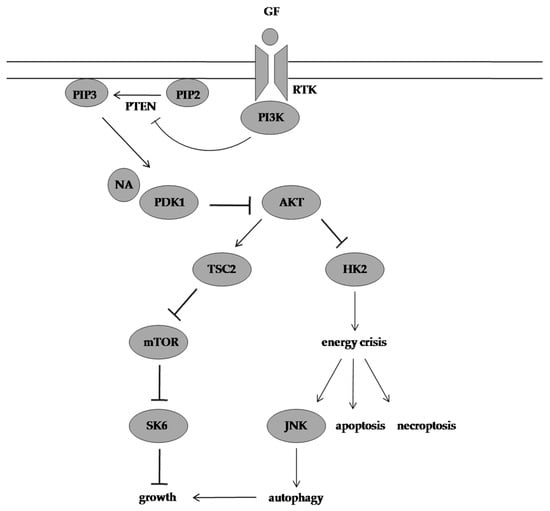

2. GL22 Suppressed Tumour Growth by Altering Lipid Homeostasis and Triggering Cell Death

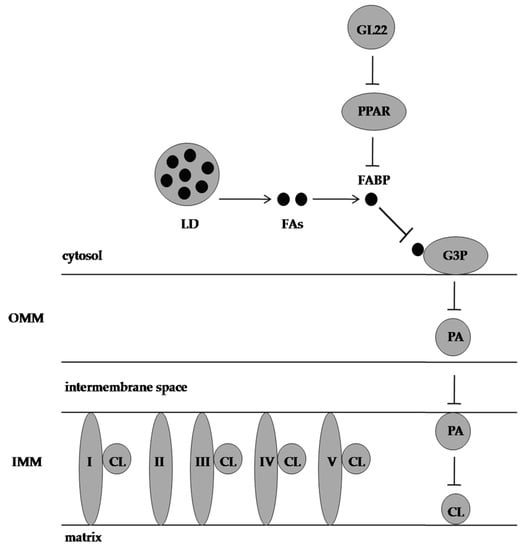

3. Grifolin Reversed DNA Methyltransferase 1-Mediated Metabolic Reprogramming Induced by Epstein-Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 1

4. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Exhibited Proapoptotic Effects by Counteracting Altered Lipid Metabolism

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules28031441

References

- Patel, S.; Goyal, A. Recent Developments in Mushrooms as Anti-Cancer Therapeutics: A Review. 3 Biotech 2012, 2, 1–15.

- Zheng, H.D.; Liu, P.G. Additions to Our Knowledge of the Genus Albatrellus (Basidiomycota) in China. Fungal Divers. 2008, 32, 157–170.

- Hellwig, V.; Nopper, R.; Mauler, F.; Freitag, J.; Ji-Kai, L.; Zhi-Hui, D.; Stadler, M. Activities of Prenylphenol Derivatives from Fruitbodies of Albatrellus Spp. on the Human and Rat Vanilloid Receptor 1 (VR1) and Characterisation of the Novel Natural Product, Confluentin. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Med. Chem. 2003, 336, 119–126.

- Liu, Q.; Shu, X.; Wang, L.; Sun, A.; Liu, J.; Cao, X. Albaconol, a Plant-Derived Small Molecule, Inhibits Macrophage Function by Suppressing NF-ΚB Activation and Enhancing SOCS1 Expression. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2008, 5, 271–278.

- Luo, X.; Li, L.; Deng, Q.; Yu, X.; Yang, L.; Luo, F.; Xiao, L.; Chen, X.; Ye, M.; Liu, J. Grifolin, a Potent Antitumour Natural Product Upregulates Death-Associated Protein Kinase 1 DAPK1 via p53 in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011, 47, 316–325.

- Deng, Q.; Yu, X.; Xiao, L.; Hu, Z.; Luo, X.; Tao, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Ding, Z. Neoalbaconol Induces Energy Depletion and Multiple Cell Death in Cancer Cells by Targeting PDK1-PI3-K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e804.

- Ajith, T.A.; Janardhanan, K.K. Indian Medicinal Mushrooms as a Source of Antioxidant and Antitumor Agents. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2007, 40, 157–162.

- Cao, Y.; Yuan, H.S. Ganoderma mutabile Sp. Nov. from Southwestern China Based on Morphological and Molecular Data. Mycol. Prog. 2013, 12, 121–126.

- Hapuarachchi, K.K.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Phengsintham, P.; Yang, H.D.; Kakumyan, P.; Hyde, K.D.; Wen, T.C. Ganodermataceae (Polyporales): Diversity in Greater Mekong Subregion Countries (China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam). Mycosphere 2019, 10, 221–309.

- Luangharn, T.; Mortimer, P.E.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J. Domestication of Ganoderma leucocontextum, G. resinaceum, and G. gibbosum Collected from Yunnan Province, China. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia. 2020, 17, 7–26.

- Sanodiya, B.S.; Thakur, G.S.; Baghel, R.K.; Prasad, G.; Bisen, P.S. Ganoderma lucidum: A Potent Pharmacological Macrofungus. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2009, 10, 717–742.

- Wang, K.; Bao, L.; Xiong, W.; Ma, K.; Han, J.; Wang, W.; Yin, W.; Liu, H. Lanostane Triterpenes from the Tibetan Medicinal Mushroom Ganoderma Leucocontextum and Their Inhibitory Effects on HMG-CoA Reductase and α-Glucosidase. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1977–1989.

- Liu, G.; Wang, K.; Kuang, S.; Cao, R.; Bao, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, C. The Natural Compound GL22, Isolated from Ganoderma Mushrooms, Suppresses Tumor Growth by Altering Lipid Metabolism and Triggering Cell Death. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 689.

- Young, L.S.; Yap, L.F.; Murray, P.G. Epstein–Barr Virus: More than 50 Years Old and Still Providing Surprises. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016, 16, 789–802.

- Xiao, L.; Hu, Z.Y.; Dong, X.; Tan, Z.; Li, W.; Tang, M.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Tao, Y.; Jiang, Y. Targeting Epstein–Barr Virus Oncoprotein LMP1-Mediated Glycolysis Sensitizes Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma to Radiation Therapy. Oncogene 2014, 33, 4568–4578.

- Lo, A.K.F.; Dawson, C.W.; Young, L.S.; Ko, C.W.; Hau, P.M.; Lo, K.W. Activation of the FGFR1 Signalling Pathway by the Epstein–Barr Virus-encoded LMP1 Promotes Aerobic Glycolysis and Transformation of Human Nasopharyngeal Epithelial Cells. J. Pathol. 2015, 237, 238–248.

- Zhang, J.; Jia, L.; Lin, W.; Yip, Y.L.; Lo, K.W.; Lau, V.M.Y.; Zhu, D.; Tsang, C.M.; Zhou, Y.; Deng, W. Epstein-Barr Virus-Encoded Latent Membrane Protein 1 Upregulates Glucose Transporter 1 Transcription via the MTORC1/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathways. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02168-16.

- Luo, X.; Hong, L.; Cheng, C.; Li, N.; Zhao, X.; Shi, F.; Liu, J.; Fan, J.; Zhou, J.; Bode, A.M. DNMT1 Mediates Metabolic Reprogramming Induced by Epstein–Barr Virus Latent Membrane Protein 1 and Reversed by Grifolin in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 619.

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Chen, J.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.C.; Zhao, R.L.; Callac, P.; Hyde, K.D. Mycosphere Essay 8: A Review of Genus Agaricus in Tropical and Humid Subtropical Regions of Asia. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 417–439.

- Zhao, R.L.; Zhou, J.L.; Chen, J.; Margaritescu, S.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Callac, P.; Parra, L.A.; Li, G.J.; Moncalvo, J.M. Towards Standardizing Taxonomic Ranks Using Divergence Times—A Case Study for Reconstruction of the Agaricus Taxonomic System. Fungal Divers. 2016, 78, 239–292.

- Zhang, M.Z.; Li, G.J.; Dai, R.C.; Xi, Y.L.; Wei, S.L.; Zhao, R.L. The Edible Wide Mushrooms of Agaricus Section Bivelares from Western China. Mycosphere 2017, 8, 1640–1652.

- Jagadish, L.K.; Krishnan, V.V.; Shenbhagaraman, R.; Kaviyarasan, V. Comparitive Study on the Antioxidant, Anticancer and Antimicrobial Property of Agaricus Bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach before and after Boiling. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 654–661.

- Dhamodharan, G.; Mirunalini, S. A Novel Medicinal Characterization of Agaricus Bisporus (White Button Mushroom). Pharmacologyonline 2010, 2, 456–463.

- Savoie, J.M.; Foulongne-Oriol, M.; Barroso, G.; Callac, P. 1 Genetics and Genomics of Cultivated Mushrooms, Application to Breeding of Agarics. In Agricultural Applications, 2nd ed.; Esser, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 11, pp. 3–33.

- Thawthong, A.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Thongklang, N.; Chukeatirote, E.; Kakumyan, P.; Chamyuang, S.; Rizal, L.M.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.; Callac, P. Discovering and Domesticating Wild Tropical Cultivatable Mushrooms. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2014, 41, 731–764.

- Largeteau, M.L.; Llarena-Hernández, R.C.; Regnault-Roger, C.; Savoie, J.M. The Medicinal Agaricus Mushroom Cultivated in Brazil: Biology, Cultivation and Non-Medicinal Valorisation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 897–907.

- Wisitrassameewong, K.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Thongklang, N.; Zhao, R.; Callac, P.; Moukha, S.; Ferandon, C.; Chukeatirote, E.; Hyde, K.D. Agaricus subrufescens: A Review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 19, 131–146.

- Camelini, C.M.; Rezzadori, K.; Benedetti, S.; Proner, M.C.; Fogaça, L.; Azambuja, A.A.; Giachini, A.J.; Rossi, M.J.; Petrus, J.C.C. Nanofiltration of Polysaccharides from Agaricus subrufescens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9993–10002.

- Dui, K.D.H.; Zhao, R. Edible Species of Agaricus (Agaricaceae) from Xinjiang Province (Western China). Phytotaxa. 2015, 202, 185–197.

- Muszynska, B.; Kala, K.; Rojowski, J.; Grzywacz, A.; Opoka, W. Composition and Biological Properties of Agaricus Bisporus Fruiting Bodies-a Review. Polish J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017, 67, 173–182.

- Bhushan, A.; Kulshreshtha, M. The Medicinal Mushroom Agaricus bisporus: Review of Phytopharmacology and Potential Role in the Treatment of Various Diseases. J. Nat. Sci. Med. 2018, 1, 4–9.

- Chen, S.; Oh, S.R.; Phung, S.; Hur, G.; Ye, J.J.; Kwok, S.L.; Shrode, G.E.; Belury, M.; Adams, L.S.; Williams, D. Anti-Aromatase Activity of Phytochemicals in White Button Mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus). Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 12026–12034.

- Adams, L.S.; Chen, S.; Phung, S.; Wu, X.; Ki, L. White Button Mushroom (Agaricus Bisporus) Exhibits Antiproliferative and Proapoptotic Properties and Inhibits Prostate Tumor Growth in Athymic Mice. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 744–756.