Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The ability of microwave radiometry (MWR) to detect with high accuracy in-depth temperature changes in human tissues is under investigation in various medical fields. The need for non-invasive, easily accessible imaging biomarkers for the diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory arthritis provides the background for this application in order to detect the local temperature increase due to the inflammatory process by placing the appropriate MWR sensor on the skin over the joint.

- microwave radiometry

- synovitis

- imaging biomarker

- ultrasound

- rheumatoid arthritis

1. Rationale

The rationale for the use of microwave radiometry (MWR) in inflammatory arthritis is the rise of tissue temperature due to the joint inflammatory process. The local alterations in the synthesis and release of immune mediators in response to injury result in altered biochemical processes and temperature local changes. Indeed, although further studies are warranted, existing evidence suggests that local inflammation in arthritis results in an increased in-depth temperature that can be detected by the MWR sensor, which is placed on the skin over the inflamed joints. Since local temperature changes precede structural changes, it is of paramount importance to diagnose inflammatory changes as early as possible, even if signs and symptoms suggestive of inflammation are absent.

As early as 1949, Horvath and Hollander observed that the temperature of synovial fluid was directly dependent on the relative hyperemia of the synovium [1]. Interest-ingly, the hypervascularization of the synovial membrane, detected as a power doppler (PD) sign by ultrasound, and subclinical persistent synovitis are more strongly associated with disease activity and radiographic changes than clinical and laboratory parameters [2][3]. Likewise, in sacroiliitis, no association has been previously demonstrated between inflammatory sacroiliac changes and inflammatory markers or clinical findings [4].

2. Technique

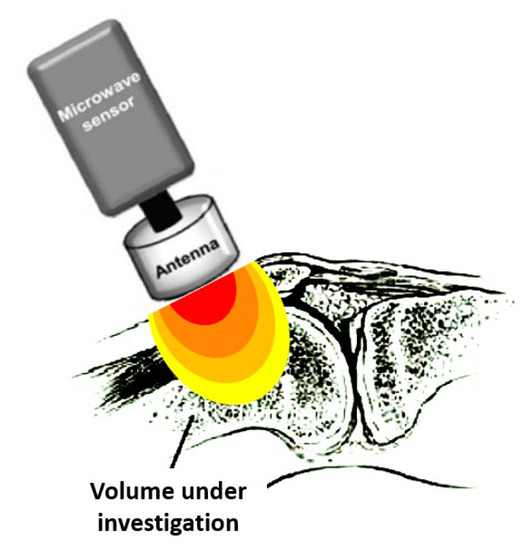

RTM-01-RES (Figure 1) is the commercially available instrument used in most of the studies; however, technical modifications, including different types of sensors and antennas, have been reported, as well as the design of newer devices, such as portable ones [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. The RTM-01-RES microwave computer-based system detects the temperature of internal tissues at microwave frequencies, with an accuracy of ±0.2 °C within seconds. The measurement depth depends on the diameter of the sensor used, which touches the surface of the skin. During measurements, the individual lies in a supine position, and the microwave antenna of the device is placed flat on the joint, as shown in Figure 1. The antenna is held in this position for 10 sec. This time is required for the integration of the microwave emission by the receiver and for the conversion of the measured signal to temperature by a microprocessor.

Figure 1. The measured temperature is the average temperature within the volume in the vicinity of the antenna, weighted according to its sensitivity pattern (lobe). The temperature of the dark (red) area volume is of more weight in the measurement than that of the volume in the light (yellow) area. Modified from Zampeli et al. [14].

The sensor’s measurement depends on the antenna used since it is a distributed weighted average of temperature within the sensitivity lobe of the antenna [15], as depicted in Figure 1. Therefore, the spatial temperature resolution of the sensor depends strongly on how narrow the sensitivity lobe is. The sensitivity is stronger near the front of the antenna and fades out when moving away from it, having a typical three-dimensional form, as shown in Figure 1.

Although the temperature of object(s) (i.e., the joint) in the vicinity of the antenna is highly weighted and dominates the resulting measurement, the temperature of the surrounding environment, i.e., the air (as well as its electrical properties), impacts the measurement directly (due to being weight-averaged by the antenna) and implicitly (via its impact on the patient’s overall body temperature). To this end, the ambient temperature is of great importance [16]. Notably, others have previously reported that the joint temperature is influenced by seasonal (winter vs. summer) temperature variations [1]. Thus, the examination should be performed at a predefined room temperature. It is recommended that all subjects rest for at least 10 min in an examination room with a steady temperature (21–23 °C) to equilibrate to the ambient temperature before starting the measurements [17]. Moreover, since the measurement result depends on the electromagnetic coupling between the antenna and its surroundings, electronic devices radiating signals within the frequency sensitivity range of the instrument should be silenced, and metallic objects should be moved away.

Regarding the role of intrinsic factors, the geometry and electrical properties of the joint (resulting from biological tissue physicochemical properties) are important. In a previous study, no association was demonstrated between the obtained measured values and patient characteristics such as age, gender, smoking, body mass index, history of diabetes or hypothyroidism, as well as daily prednisolone dose and the use of biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs [17]. Nevertheless, circadian rhythm, metabolic rate, calorific intake, smoking, physical activity, emotional states such as pain or fear, and atmospheric humidity have all been previously described as parameters that may also have an impact on body temperature [1][18]. For example, small changes in vascular tone can cause large changes in tissue temperature. Thus, there are many uncontrollable factors in the experiment. This may result in significantly different measurements from one patient to another, even from a single joint of one patient at different measurement times. These variations challenge the definition of a standard “normal” temperature [18]. More research is required to determine adjustments for other factors when using MWR to assess arthritis.

Since no reliable data are available on normal absolute temperature cut-offs, the relative temperature, e.g., the difference in temperature (Δt) between two examined areas per joint or between the joint and a control point, is usually calculated. Indeed, Salisbury et al. found that physiological or environmental changes of any individual can shift up or down the heat distribution patterns of a joint, although the actual thermal spread of the heat pattern is constant [18]. This implies a constant relative thermal measurement throughout the day, although the absolute temperature value may vary. Therefore, methods of detecting inflammation using absolute temperature measurement are subject to errors due to these diurnal circadian temperature changes in contrast to those based on relative temperature distribution due to the relative stability of these heat patterns.

The temperature difference observed in healthy individuals between the different joint areas was eliminated in inflamed joints, the temperature of which was globally increased [17]. This resulted in lower Δt values in inflamed vs. non-inflamed joints. Overall, the use of MWR showed good intra- and inter-class correlation coefficients, 0.94 and 0.93, respectively, indicating perfect agreement.

3. Assessment of Large Joints: Knee, Elbow, and Lower Leg

The first joints assessed by MWR were the knees, as early as 1987, when Fraser et al. scanned 52 knees and demonstrated a strong correlation between the microwave thermographic index and the measured clinical and laboratory parameters [19]. Some years later, two studies showed that microwave thermography reflects the clinical change after intra-articular treatment intervention in the rheumatoid knee [20][21]. Based on these findings, in a proof-of-concept study, researchers tested the hypothesis that increased local temperature detected by MWR reflects subclinical synovial inflammation [14]. Indeed, in 40 RA and 20 osteoarthritis (OA) knees, in the absence of relevant clinical signs, subclinical inflammation detected by ultrasound (fluid effusion and/or PD signal) was characterized by significantly higher absolute (but lower Δt) temperature measurements. Following this study, Ravi et al. used a custom-built radiometer to record the temperature at the lateral and medial compartments of both knees in 41 individuals older than 35 years. In this pilot study, a statistically significant rise in the radiometer temperature was observed at the diseased sites (RA, OA, trauma), unlike the healthy sites [5].

Taking into consideration these observations, in a recent more thorough approach, researchers tested 82 patients with RA, 26 with OA, as well as healthy controls, and found a stronger inter-rater agreement of MWR with ultrasound-derived PD signs of synovial inflammation (82%) than with clinical examination of the joint (76%) [17]. Interestingly, knees of RA patients with synovitis scored ≥2 or PD activity had significantly lower relative temperature Δt than clinically and sonographically normal knees, while normal knees of patients with RA had comparable temperature values with healthy controls as well as knees with OA. In contrast to RA, the grading of synovial fluid in OA was not associated with the level of the recorded temperature. Among RA patients, MWR had 75% sensitivity and 73% specificity for the detection of knee synovitis scored ≥2, while 80% sensitivity and 82% specificity for PD activity. At the same time, MWR performed well in the discrimination between sonographically abnormal RA knees and knees of patients with OA or healthy controls (83–98% sensitivity, 76–80% specificity). These results are strengthened by a validation assessment of MWR knee measurements in an independent cohort of 31 patients with painful knees, where a knee Δt score of ≤0.2 predicted power Doppler positivity, with 100% positive and negative predictive values.

In the same study, the relative temperature Δt of other large joints (elbow, lower leg) was lower in RA versus controls; nevertheless, MWR performed moderately and similarly to clinical examination in the detection of (teno)synovitis or ultrasound-derived PD sign in these joints.

Subsequently, in a review on imaging diagnostics, Tarakanov et al. referred to the use of MWR in order to determine the depth temperature in the projection of knee joints in 43 children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis as well as 43 healthy children. The authors suggested that clinical visual assessment of temperature data provides an instant idea of thermal asymmetry, which may be used in order to assess diseased versus healthy joints as well as changes in temperature fields observed during the disease course [22].

4. Assessment of Small Joints: Wrist, Metacarpal Proximal Interphalangeal, and Metatarsophalangeal Joints

The examination of small joints by MWR was systematically assessed by [17][23]. Taking into consideration that small joints are mainly affected in RA, in a prospective pilot study, researchers evaluated 10 patients with active, untreated RA and tested whether the temperature of the small joints, measured by MWR, correlates to disease activity. All patients underwent clinical and laboratory assessments, joint ultrasound, and MWR of the hand joints in serial evaluations up to 3 months after treatment onset [23]. By summing up the relative temperature of 16 joints (second to fifth metacarpal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints), bilaterally, researchers created a thermo-score of small joints, which correlated significantly to the standard disease activity score DAS28, the C-reactive protein serum levels, tender and swollen joint counts, the patient’s visual analog scale, and the standard 7-joint ultrasound score of small joints (US7). Moreover, a statistically significant difference in the thermo-score was observed between patients in high/moderate disease activity/remission versus those in low disease activity/remission or healthy subjects, and individual changes from baseline to the end of follow-up mirrored the corresponding DAS28 changes in the majority of patients.

In a subsequent study, the diagnostic performance of MWR at the single small joint level was tested in 82 patients with RA, 26 patients with OA, and healthy controls [17]. The diagnostic performance of MWR was moderate and similar to clinical examination in the detection of (teno)synovitis or PD in the joints included in the US7 ultrasound score, e.g., the wrist, MCP-2 and -3, PIP-2 and -3, and metatarsophalangeal (MTP)-2 and -5.

5. Sacroiliac Joint and Low Back Pain Assessment

The first observation with regard to the examination of sacroiliac (SI) joints and lumbar spine with MWR was described in 1987 by Fraser et al. [19]. In ankylosing spondylitis, an almost flat temperature pattern appeared in the lumbar spine in contrast to the normally observed temperature rise at the center of the spine. Nevertheless, the authors were not able to quantify this difference using a numerical form.

Recently, fair sensitivity and specificity of MWR measurements were demonstrated for axial involvement diagnosis in 58 patients with spondyloarthritis [17][24]. In particular, patients with active or chronic sacroiliitis were characterized by significantly lower relative temperature of the sacroiliac (SI) joints (derived by three measurements along the joint area) compared to patients without sacroiliitis or healthy controls (74% sensitivity/78% specificity and 74% sensitivity/72% specificity, respectively). The fact that the presence of bone marrow edema in acute lesions and fat degeneration in chronic lesions were associated with a statistically significant change in the temperature of SI joints may be explained by the presence of inflammatory activity in patients with chronic SI lesions and the better sensitivity of MWR in detecting inflammation. In fact, MWR was able to detect inflammatory SI joint changes in patients with active non-radiological sacroiliitis and in 75% of patients with clinically silent, albeit active, disease in magnetic resonance imaging. MWR measurements showed no correlation to the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, the patient pain Visual Analogue Scale for SI joints, the New York radiological grading of SI lesions [25], and C-reactive protein levels.

Interestingly, another group has recently investigated the diagnostic role of MWR in patients with low back pain [26][27]. In particular, 48 patients with clinically confirmed acute or sub-acute low back pain and controls were examined by MWR at the level of the spinous processes of the L1 to L5 vertebral bodies along the median, left, and right para-vertebral lines. The area of pathological muscle spasm and/or inflammation in the projection of the vertebral-motor segment was identified by the visualization of thermal asymmetry. The highest internal temperature was observed in patients with the most severe pain and those examined within the first week after the exacerbation. The application of targeted treatment methods resulted in a significant fall in the maximum and normalization of the gradient of internal temperature and, at the same time, a decrease in thermo-asymmetry.

6. Global Disease Activity Assessment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Given the need for new biomarkers, researchers tried to evaluate global disease activity in RA patients using MWR. Therefore, researchers assessed small and large joints unilaterally in 56 RA patients who underwent MWR and ultrasound examination simultaneously in the clinically dominant hand/arm and foot/leg in seven small joints (wrist, MCP-2 and -3, PIP-2 and -3, MTP-2 and -5), according to the US7 ultrasound score and three large joints (elbow, knee, ankle) [17]. A statistically significant correlation was shown between the MWR-derived thermo-score of small and large joints and the tender/swollen joint counts, the patient’s and physician’s Visual Analogue Scale, DAS28, inflammatory markers, and the ultrasound scores of synovitis/tenosynovitis. Interestingly, the 10-joint thermo-score was sensitive enough to detect subclinical inflammation since the inter-rater agreement with ultrasound-defined joint inflammation was stronger compared to DAS28 clinical assessment (82% versus 64%). It is of note that 9 out of 11 patients with quiescent disease based on DAS28, albeit active in ultrasound, had a thermo-score indicative of active disease. In addition, a statistically significant difference was observed in the thermo-score among RA disease activity stages. A thermo-score cut-off value of ≤12.1 could discriminate between sonographically-defined RA activity stages with 84% sensitivity/73% specificity. In addition, the thermo-score could discriminate between RA and OA patients with 82% sensitivity/60% specificity and between RA patients and healthy subjects with 74% sensitivity/69% specificity. Finally, researchers demonstrated the potential role of MWR as a measure of therapeutic response since individual changes in MWR measurements from baseline to follow-up in 20 patients with active disease at baseline mirrored the corresponding DAS28 and ultrasound changes in most patients.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics13040609

References

- Horvath, S.M.; Hollander, J.L. Intra-Articular Temperature as a Measure of Joint Reaction. J. Clin. Investig. 1949, 28, 469–473.

- Nguyen, H.; Ruyssen-Witrand, A.; Gandjbakhch, F.; Constantin, A.; Foltz, V.; Cantagrel, A. Prevalence of ultrasound-detected residual synovitis and risk of relapse and structural progression in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical remission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 2110–2118.

- Fukae, J.; Tanimura, K.; Atsumi, T.; Koike, T. Sonographic synovial vascularity of synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2014, 53, 586–591.

- Taylor, H.G.; Wardle, T.; Beswick, E.J.; Dawes, P.T. The relationship of clinical and laboratory measurements to radiological change in ankylosing spondylitis. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1991, 30, 330–335.

- Ravi, V.M.; Sharma, A.K.; Arunachalam, K. Pre-Clinical Testing of Microwave Radiometer and a Pilot Study on the Screening Inflammation of Knee Joints. Bioelectromagnetics 2019, 40, 402–411.

- Momenroodaki, P.; Haines, W.; Fromandi, M.; Popovic, Z. Noninvasive internal body temperature tracking with near-field microwave radiometry. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2017, 66, 2535–2545.

- Fedoseeva, E.; Shchukin, G.; Rostokin, I. Calibration of a Tri-Band Microwave Radiometric System with Background Noise Compensation. Meas. Tech. 2020, 63, 301–307.

- Tisdale, K.; Bringer, A.; Kiourti, A. Development of a Coherent Model for Radiometric Core Body Temperature Sensing. IEEE J. Electromagn. RF Microw. Med. Biol. 2022, 6, 355–363.

- Tisdale, K.; Bringer, A.; Kiourti, A. A Core Body Temperature Retrieval Method for Microwave Radiometry When Tissue Permittivity is Unknown. IEEE J. Electromagn. RF Microw. Med. Biol. 2022, 6, 470–476.

- Livanos, N.-A.; Hamma, S.; Nikolopoulos, C.D.; Baklezos, A.; Capsalis, C.N.; Koulouras, G.E.; Charamis, P.I.; Vardiambasis, I.O.; Nassiopoulos, A.; Kostopoulos, S.A.; et al. Design and Interdisciplinary Simulations of a Hand-Held Device for Internal-Body Temperature Sensing Using Microwave Radiometry. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 2421–2433.

- Gudkov, A.G.; Leushin, V.Y.; Vesnin, S.G.; Sidorov, I.A.; Sedankin, M.K.; Solov’ev, Y.V.; Agasieva, S.V.; Chizhikov, S.V.; Gorbachev, D.A.; Vidyakin, S.I. Studies of a Microwave Radiometer Based on Integrated Circuits. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 53, 413–416.

- Vesnin, S.G.; Sedankin, M.K.; Ovchinnikov, L.M.; Gudkov, A.G.; Leushin, V.Y.; Sidorov, I.A.; Goryanin, I. Portable microwave radiometer for wearable devices. Nexo 2021, 34, 1431–1447.

- Losev, A.G.; Khoperskov, A.V.; Astakhov, A.S.; Suleymanova, H.M. Problems of measurement and modeling of thermal and radiation fields in biological tissues: Analysis of microwave thermometry data. Math. Phys. Comp. Simul. 2015, 6, 31–71.

- Zampeli, E.; Raftakis, I.; Michelongona, A.; Nikolaou, C.; Elezoglou, A.; Toutouzas, K.; Siores, E.; Sfikakis, P.P. Detection of subclinical synovial inflammation by microwave radiometry. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64606.

- Cheever, E.A.; Foster, K.R. Microwave radiometry in living tissue: What does it measure? IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng. 1992, 39, 563–568.

- Tarakanov, A.V.; Tarakanov, A.A.; Vesnin, S.; Efremov, V.V.; Roberts, N.; Goryanin, I. Influence of Ambient Temperature on Recording of Skin and Deep Tissue Temperature in Region of Lumbar Spine. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 21–26.

- Laskari, K.; Pentazos, G.; Pitsilka, D.; Raftakis, J.; Konstantonis, G.; Toutouzas, K.; Siores, E.; Tektonidou, M.; Sfikakis, P.P. Joint microwave radiometry for inflammatory arthritis assessment. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 839–844.

- Salisbury, R.S.; Parr, G.; De Silva, M.; Hazleman, B.L.; Page-Thomas, D.P. Heat distribution over normal and abnormal joints: Thermal pattern and quantification. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1983, 42, 494–499.

- Fraser, S.M.; Land, D.V.; Sturrock, R.D. Microwave thermography in rheumatic disease. Eng. Med. 1987, 16, 209–212.

- MacDonald, A.G.; Land, D.V.; Sturrock, R.D. Microwave thermography as a noninvasive assessment of disease activity in inflammatory arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 1994, 13, 589–592.

- Blyth, T.; Stirling, A.; Coote, J.; Land, D.; Hunter, J.A. Injection of the rheumatoid knee: Does intra-articular methotrexate or rifampicin add to the benefits of triamcinolone hexacetonide? Br. J. Rheumatol. 1998, 37, 770–772.

- Tarakanov, A.V.; Ladanova, E.S.; Lebedenko, A.A.; Tarakanova, T.D.; Vesnin, S.G.; Goryanin, I.I. Passive Microwave Radiometry (MWR) as a Component of Imaging Diagnostics in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA). Rheumato 2022, 2, 55–68.

- Pentazos, G.; Laskari, K.; Prekas, K.; Raftakis, J.; Sfikakis, P.P.; Siores, E. Microwave radiometry-derived thermal changes of small joints as additional potential biomarker in rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective pilot study. JCR 2018, 24, 259–263.

- Laskari, K.; Pitsilka, D.A.; Pentazos, G.; Siores, E.; Tektonidou, M.G.; Sfikakis, P.P. SAT0657. Microwave radiometry-derived thermal changes of sacroiliac joints as a biomarker of sacroiliitis in patients with spondyloarthropathy. ARD 2018, 77 (Suppl. 2), 1178.

- Van der Linden, S.; Valkenburg, H.A.; Cats, A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984, 27, 361–368.

- Tarakanov, A.V.; Tarakanov, A.A.; Vesnin, S.; Efremov, V.V.; Goryanin, I.; Roberts, N. Microwave Radiometry (MWR) temperature measurement is related to symptom severity in patients with Low Back Pain (LBP). J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2021, 26, 548–552.

- Tarakanov, A.V.; Tarakanov, A.A.; Kharybina, T.; Goryanin, I. Treatment and Companion Diagnostics of Lower Back Pain Using Self-Controlled Energo-Neuroadaptive Regulator (SCENAR) and Passive Microwave Radiometry (MWR). Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1220.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!