Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Pharmacology & Pharmacy

Self-assembled peptides are monomeric assemblies of short or repetitive amino acid sequences formed into nanostructured peptide assemblies that exhibit unique physicochemical and biochemical activities. Among them, peptides with secondary structures, amphiphilic peptides, ionic-complementary peptides and trans-stimulation-responsive peptides can self-assemble into different nanostructures.

- peptides

- self-assembly

- nanostructures

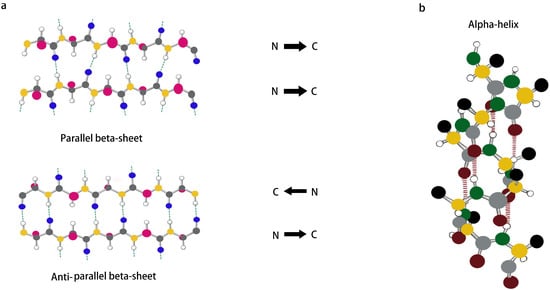

1. β-Sheet

Inspired by the sequence (Ac(AEAEAKAK)2-CONH2) found in zuotin, a Z-DNA-binding yeast peptide [2], many β-sheet structures have been formed, and many self-assembled peptide structures have already been designed. β-Sheets are flattened sheet-like structures formed by parallel or antiparallel arrangements of peptides that stabilize the structure of the peptide by interchain hydrogen bonding with neighboring main-chain amides, as shown in Figure 2a. Polypeptides forming β-sheets and supramolecular self-assembled structures usually contain 16–20 amino acids with an alternating distribution of polar and non-polar amino acids. In particular, the β-sheet structure separates the hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions of the peptide sequence, providing amphiphilicity to the peptide and driving the peptide self-assembly process. For example, a peptide comprising hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids was designed wherein the β-sheet was driven to grow axially into a protofibrillar nanostructure with a hydrophobic and hydrophilic surface, producing a bilayer structure that reduced the likelihood of the hydrophobic surface coming into contact with water [40,41]. β-hairpin peptides are derivatives of β-turns and usually consist of two hydrogen-bonded antiparallel β-chains bridged by reverse turns. Initially, Schneider et al. designed a class of MAX1 peptides consisting of alternating lysine and valine residues that could fold into a β-hairpin structure under the influence of external factors and then self-assemble into rigid hydrogels [42]. It has been shown that electrostatic interactions can also affect the formation of β-hairpin structures. By increasing the pH of the solution or the salt concentration of the solution to shield the electrostatic interactions, the peptides can form β-hairpin structures with hydrophilic lysine residues as the inner surface and hydrophobic valine residues as the outer surface, and they can then finally use their hydrophobic effect to self-assemble to form nanofibers [43,44,45].

Figure 2. (a,b) Schematic representation of β-sheet and α-helix secondary structures.

2. α-Helix

The α-helix, which is usually formed by winding the peptide backbone into a right-handed helix containing 3.6 amino acids per turn, is an important secondary structure type in protein- and peptide-like structures and is also one of the main structures present inside a portion of peptide hydrogels. Unlike the structure of a β-sheet, an α-helix is formed by a single peptide chain in which the main-chain amide component is an intramolecular hydrogen bond, as shown in Figure 2b. Although α-helices are easy to synthesize and modify, linear peptides containing α-helical structures still lose their helical conformation in solution due to their inherent thermodynamic instability [46]. Therefore, stabilization of the α-helical structure is important for triggering the self-assembly of peptides [47,48,49]. It was found that side chain cross-coupling, hydrogen bonding substitution and the formation of salt bridges can be used to stabilize α-helical structures. Mihara et al. designed an α-helical structure with seventeen peptide segments, and they stabilized the α-helical structure using two sets of EK salt bridges and then further self-assembled it into a nanostructure [50]. In addition, Lee et al. showed that peptide self-assembly mediated by β-sheets can also be used to stabilize α-helix structures, which can enable peptides to self-assemble into nanostructures in solution [51]. The self-assembly of α-helices is achieved mainly by “helical coils”, which have good surface interactions between the helices and thus can generate helical beams [52]. Although most nanofiber assembly comes from β-sheet structures, nanofibrils and other nanostructures can also be formed from α-helical polypeptides by hydrophobic segment modification [53] and the lateral binding of multiple helical coils [54,55].

3. Surfactant-Like Peptides

In general, surfactant-like peptides are composed of a hydrophilic head attached to a hydrophobic tail. The hydrophilic head generally consists of one or two charged amino acid residues (His, Asp, Glu), and the hydrophobic tail generally consists of between three and nine nonpolar amino acids (Ala, Phe, Ile, Val). When dispersed in aqueous solutions, they tend to self-assemble and hide their hydrophobic tails through polar interfaces, a behavior that enables the formation of nanostructures such as nanotubes or nanocapsules [56]. Nanotubes or nanocapsules become the main structures formed by the assembly of surfactant-like peptides through self-assembly, and they can act on cellular lipid bilayers in a similar way to lipid-scavenging micelles [57,58]. There is also a specific peptide, called bola-amphiphilic peptide, that exhibits a different linkage, where a hydrophobic sequence located at the center can be linked to charged amino acids at both ends [59]. The difference between bola-amphiphilic peptides and surfactant-like peptides is the number of hydrophilic head groups on the building blocks: surfactant-like peptides have only one head, whereas bola-amphiphilic peptides have two hydrophilic heads with two hydrophilic groups spaced by hydrophobic sites at both ends [60,61]. Given their structural similarities, bola-amphiphilic peptides can display surfactant-like peptide properties. It has been shown that the two heads of bola-amphiphilic peptides are usually positively charged amino acids (KAAAAK, KAAAAAAK and RAAAAAR) capable of binding to negative residues of nucleotides that are often used to bind DNA/RNA [62].

4. Amphiphilic Peptides

The structure of amphiphilic peptides is similar to that of lipid molecules and is most typically characterized by the attachment of hydrophobic long-chain alkyl groups to hydrophilic peptides. The hydrophilic head and hydrophobic tail of amphiphilic peptides can interact with each other to stabilize various supramolecular structures by inter- and intramolecular driving forces, and they can also generate nanostructures with different morphologies [63,64,65]. As novel self-assembled peptide nanomaterials, amphiphilic peptides are of interest because of their simplicity, versatility and biocompatibility. In terms of their biomedical applications, amphiphilic peptides are easy to design and synthesize, thus ensuring their quality and purity. Moreover, nanostructures generated from amphiphilic peptides can show high biological activity and play an important role in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine and drug delivery [66]. Amphiphilic peptides are commonly used as carriers for the delivery of antitumor and nucleic acid drugs to their targets and have also been used to transport some therapeutic peptides. Cirillo et al. designed an amphiphilic peptide, G(IIKK)3I-NH2 (G3), for applications in targeted drug delivery. It was found that the amphipathic peptide, G3, not only has a high affinity for colon cancer cells but also has an endosomal escape ability. When the targeted siRNAs ECT2 and PLK1 were used, G3 was able to carry nucleic acids across cell membranes and successfully deliver them both to cancer cells. G3 not only has good anti-cancer activity and specificity but can also act as a gene carrier to regulate gene expression in cancer cells, which makes G3 promising as an excellent cancer therapeutic agent [67].

5. Ionic-Complementary Peptides

Ionic-complementary polypeptides are composed of alternating arrangements of hydrophilic and hydrophobic charged amino acids that can self-assemble into nanofibrous hydrogels at the molecular level. Ionic-complementary polypeptides have a unique charge distribution pattern and can be classified into three types: Type I (−+−+−+−+), Type II (−−++−−++) and Type IV (−−−−++++). Depending on their charge distribution order, they undergo self-assembly in different ways, and ionic complementary peptides can be designed rationally by repeating and combining charge distributions. At present, in addition to the initially discovered self-assembled peptide EAK16, many ionic complementarity peptides with unique advantages, such as RADA16-I and KFE8, have also been widely studied in various fields. Among them, RADA16-I, as a classical ionic complementarity peptide, has been used in biomedical and clinical fields for its ability to spontaneously form fibrous hydrogels in aqueous solutions [68]. Nevertheless, at the same time, RADA16-I exposes the common problem of most of these peptides, namely, their instability at low pH. To further consolidate the use of ionic-complementary peptides for medical applications, scientists have worked on “modifying” these peptides. Moreover, to better refine the advantages of ionic-complementary peptides, it has recently been shown that hydrogels driven by two complementary ionic peptides with opposite charges exhibit better biocompatibility with fibroblasts at physiological pH levels, once again demonstrating the potential of hydrogels for biomedical applications [69].

6. Chemical-Group-Modified Peptides

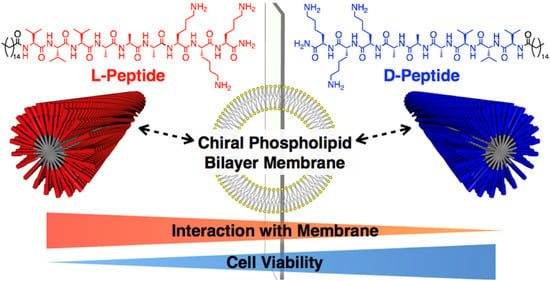

It was found that the self-assembly of peptides can be promoted by covalently binding chemical groups with self-assembly functions to peptide molecules, altering the non-covalent interactions of the peptides. Chemical-group-modified peptides exhibit an increased secondary structure, thereby making the nanobody more stable [70]. Chemical groups can play specific roles by designing corresponding functional regions in the peptide chain. Currently, linkage to hydrophobic alkyl chains is the most common modification in peptide building blocks. Hydrophobic forces, as the central force driving the self-assembly of peptides, can modify the properties and functions of peptides by designing linkages to alkyl peptide chains at the amino terminus. Sato et al. investigated the effect of peptide chirality on their cytotoxicity and cell membrane binding ability by using alkylated, modified D and L-type-V3A3K3 assembled peptides [71], as shown in Figure 3. In addition to hydrophobic alkyl chains, lipid groups and sugars can also be used to modify peptides. Sugars are involved in various life activities in the body. For example, mannose can target macrophages, while the hydroxyl group on the sugar greatly increases the hydrophilicity of the whole molecule. Xu et al. designed and synthesized an enzyme-responsive glycopeptide derivative that could be sheared by β-galactosidase in senescent cells and self-assemble into gels. The gels further induce apoptosis in senescent cells and act as clearing agents for these cells [72].

Figure 3. Chiral recognition of lipid bilayer membranes by supramolecular assemblies of peptide amphiphiles. Reprinted with permission from ref. [71]. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

7. Metal-Coordination Peptides

Metal-coordination peptides, using peptides and metal ions as building blocks, combine the advantages of peptide self-assembly and metal–ligand interactions and have good prospects for the construction of novel nanomedicines [73]. For example, histidine-rich peptides can form coordination interactions with metal ions and further self-assemble into functional supramolecular nanomaterials, which play an essential role in optoelectronic engineering [74], bio-nanotechnology [75], drug delivery and biomedicine [76]. It has been found that metal ligands can control the self-assembly behavior of peptides, which can produce different morphologies depending on the binding stoichiometry and geometry of the metal ions. Knight et al. synthesized a peptide–polymer amphiphile, oSt(His)6, which was observed to have different morphological structures in different divalent transition metal ions (Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+ and Cd2+). Aggregated micelles were observed in the presence of Zn2+, Co2+ and Cu2+, isolated micelles were observed in the orientation of Ni2+ and Cd2+, and multilayer vesicles were formed when oSt(His)6 was coordinated to Mn2+ [77]. This work demonstrated the great potential of transition metal ion coordination as a tool to guide the assembly of synthetic nanomaterials. Furthermore, peptides can also be used as templates to bind to metal surfaces to modulate metallic nanomaterials with different shapes, structures and compositions. Feng et al. used the self-assembly properties of the peptide Aβ25-35 to assemble and prepare monomers, protofibrils and mature fibers by incubating them in phosphate buffer and water for different times. Au nanoparticles, Au nanoribbons and Au nanofibers were then successfully synthesized based on these three self-assembled structures, respectively, and their catalytic activities were confirmed to be significantly higher compared to Au nanoparticles prepared without a template [78]. Thus, changes in self-assembly conditions induce differences in the self-assembled structures of peptides, which can lead to the formation of many different structures of Au nanoparticles.

8. Stimulus-Responsive Peptides

Amino acids are linked by amide bonds to produce a large number of polypeptides of different lengths and sequences, and the nature of the amino acids themselves and the order in which they are arranged in the polypeptide chain can influence the self-assembly behavior of the polypeptides. It has been found that the integration of stimuli-responsive amino acids into polypeptides can modulate the non-covalent interactions between polypeptides, thus controlling their conformation and assembly propensity. This strategy has been widely used to design stimulus-responsive peptide assembly modules, including redox-responsive peptides, pH-responsive peptides, light-responsive peptides and enzyme-responsive peptides [79]. Singh et al. designed arginine-α,β-dehydroxyphenylalanine dipeptide nanoparticles (RΔF-NPs) by encapsulating adriamycin in RΔF-NPs to form RΔF-Dox-NPs. These consisted of Dox as a functional module and RΔF-NPs as a response module. In the tumor microenvironment, RΔF-Dox-NPs have a higher drug release, an enhanced cancer cell internalization and an enhanced cytotoxicity at acidic pH, and they can serve as more effective pH-responsive drug delivery systems [80]. In recent years, enzyme-responsive drug delivery systems have also received much attention from researchers. Enzymes are highly selective biocatalysts that play a key role in many biological processes and in a variety of disease processes. Peptides are important bioactive substances in living organisms, and specific peptide sequences can be hydrolyzed by specific proteases, offering the possibility of constructing enzyme-responsive peptide carriers. Song et al. self-assembled a photosensitizer, PpIX, and an immune checkpoint inhibitor, 1-methyltryptophan, by linking them through the apoptosis enzyme-sensitive sequence DEVD to form uniformly sized nanomicelles, which were aggregated and retained for a long time in vivo by the EPR effect in the tumor region. Light exposure to the tumor area triggered the production of reactive oxygen species by the photosensitizer PpIX to induce apoptosis, which in turn generated apoptotic enzymes and promoted the release of tumor cell antigens [81]. In addition, the generated apoptotic enzymes hydrolyzed the enzyme-sensitive sequence DEVD, which induced the detachment of 1-methyltryptophan from the nanoparticles and subsequently activated an in vivo immune response for the inhibition and clearance of tumor lesions.

Polypeptides can self-assemble into a variety of nanostructures not only under endogenous stimuli such as pH, enzymes, etc. [82], but also by using external physical stimuli such as light, ultrasound, magnetic fields, etc. Li et al. designed a multi-component ligand self-assembly strategy based on combining peptides, photosensitizers and metal ions to construct metallo-nanodrugs for antitumor therapy. Under the action of metal ions, peptides and photosensitizers can perform synergistic self-assembly to form metallo-nanodrugs. Compared with photosensitizers alone and conventional drug delivery systems, metallo-nanodrugs can integrate robust blood circulation. They can target burst release, which can prolong blood circulation, increase tumor aggregation and enhance the antitumor effects of photodynamic therapy [83]. Ultrasound can also be used as a stimulation trigger for drug delivery systems, which are non-ionizing and non-invasive, have deep tissue penetration and can safely transmit acoustic energy to the appropriate local area. Sun et al. first co-assembled polylysine with Pluronic F127, which was chemically cross-linked to form a stiffness-adjustable nanogel (GenPLPF). Subsequently, they added the targeting agent ICAM-1 antibody and the chemotherapeutic agent epirubicin (GenPLPFT/EPI) to the nanogel to target tumors and enhance the anti-tumor ability actively. It was found that ultrasound modulated the deformability and stiffness of GenPLPFT/EPI, achieving a balance between prolonged blood circulation and deep tumor penetration, allowing more drugs to be accumulated in the tumor tissue. In addition, ultrasound can reduce the interstitial pressure of tumor tissue, helping to promote blood flow and more profound tumor enrichment with efficient anti-tumor effects [84].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020482

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!