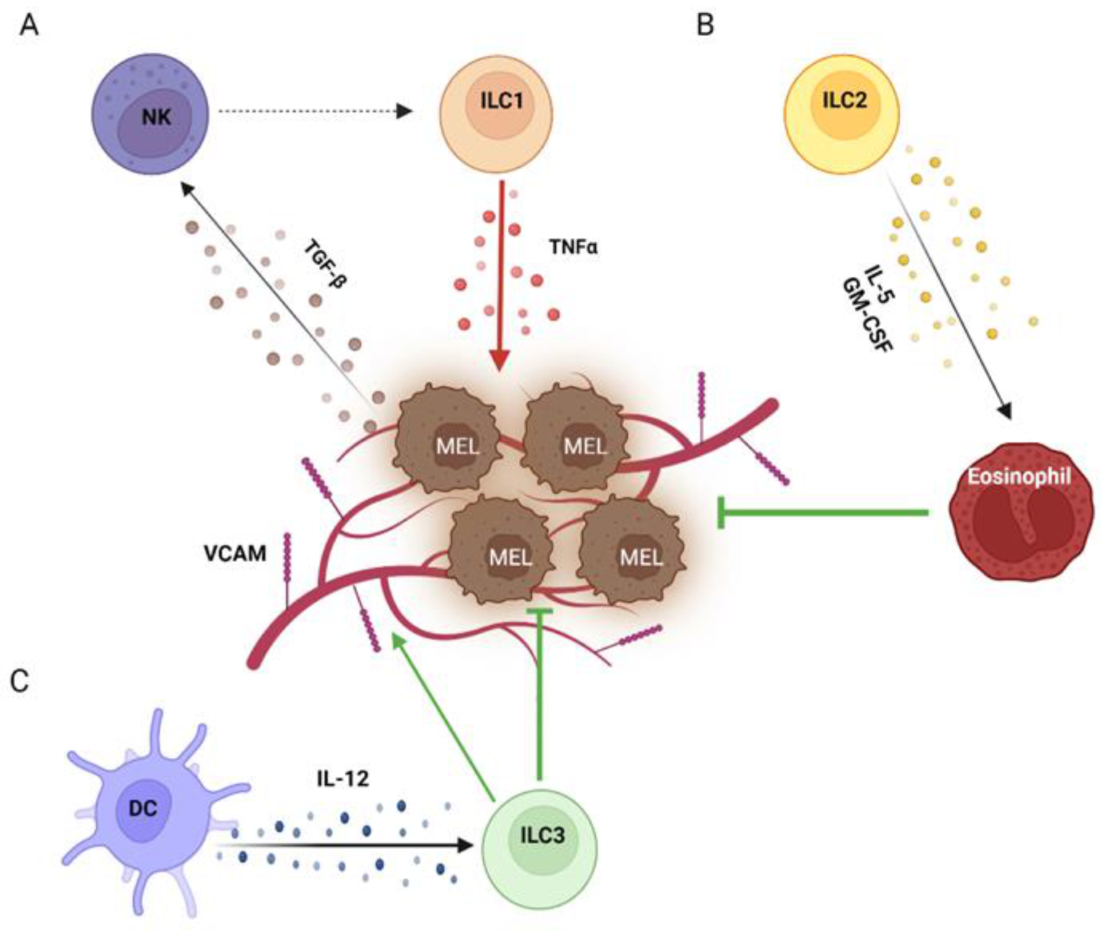

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and targeted therapy have dramatically changed the outcome of metastatic melanoma patients. Although immune checkpoints were developed based on the biology of adaptive T cells, they have subsequently been shown to be expressed by other subsets of immune cells. Similarly, the immunomodulatory properties of targeted therapy have been studied primarily with respect to T lymphocytes, but other subsets of immune cells could be affected. Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are considered the innate counterpart of T lymphocytes and include cytotoxic natural killer cells, as well as three helper subsets, ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3. Thanks to their tissue distribution and their ability to respond rapidly to environmental stimuli, ILCs play a central role in shaping immunity.

- innate lymphoid cells

- melanoma

- tumor microenvironment

1. Introduction

2. Helper Innate Lymphoid Cells in Melanoma

2.1. ILC1s in Melanoma

2.2. ILC2s in Melanoma

2.3. ILC3s in Melanoma

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers15030933

References

- Atallah, E.; Flaherty, L. Treatment of Metastatic Malignant Melanoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2005, 6, 185–193.

- Colombino, M.; Capone, M.; Lissia, A.; Cossu, A.; Rubino, C.; De Giorgi, V.; Massi, D.; Fonsatti, E.; Staibano, S.; Nappi, O.; et al. BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2522–2529.

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954.

- Chapman, P.B.; Hauschild, A.; Robert, C.; Haanen, J.B.; Ascierto, P.; Larkin, J.; Dummer, R.; Garbe, C.; Testori, A.; Maio, M.; et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2507–2516.

- Hauschild, A.; Grob, J.J.; Demidov, L.V.; Jouary, T.; Gutzmer, R.; Millward, M.; Rutkowski, P.; Blank, C.U.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; Kaempgen, E.; et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012, 380, 358–365.

- Delord, J.P.; Robert, C.; Nyakas, M.; McArthur, G.A.; Kudchakar, R.; Mahipal, A.; Yamada, Y.; Sullivan, R.; Arance, A.; Kefford, R.F.; et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation and -Expansion Study of the BRAF Inhibitor Encorafenib (LGX818) in Metastatic BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5339–5348.

- Larkin, J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Dréno, B.; Atkinson, V.; Liszkay, G.; Maio, M.; Mandalà, M.; Demidov, L.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Thomas, L.; et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1867–1876.

- Long, G.V.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Gogas, H.; Levchenko, E.; de Braud, F.; Larkin, J.; Garbe, C.; Jouary, T.; Hauschild, A.; Grob, J.J.; et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1877–1888.

- Dummer, R.; Ascierto, P.A.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.; Mandala, M.; Liszkay, G.; Garbe, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Krajsova, I.; Gutzmer, R.; et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 603–615.

- Herzberg, B.; Fisher, D.E. Metastatic melanoma and immunotherapy. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 172, 105–110.

- Hodi, F.S.; O’Day, S.J.; McDermott, D.F.; Weber, R.W.; Sosman, J.A.; Haanen, J.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Hassel, J.C.; et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 711–723.

- Robert, C.; Long, G.V.; Brady, B.; Dutriaux, C.; Maio, M.; Mortier, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Rutkowski, P.; McNeil, C.; Kalinka-Warzocha, E.; et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 320–330.

- Robert, C.; Schachter, J.; Long, G.V.; Arance, A.; Grob, J.J.; Mortier, L.; Daud, A.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Lotem, M.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2521–2532.

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Five-Year Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1535–1546.

- Burugu, S.; Dancsok, A.R.; Nielsen, T.O. Emerging targets in cancer immunotherapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 52, 39–52.

- Ambrosi, L.; Khan, S.; Carvajal, R.D.; Yang, J. Novel Targets for the Treatment of Melanoma. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 97.

- Dummer, R.; Ascierto, P.A.; Nathan, P.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D. Rationale for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Plus Targeted Therapy in Metastatic Melanoma: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1957–1966.

- Reddy, S.M.; Reuben, A.; Wargo, J.A. Influences of BRAF Inhibitors on the Immune Microenvironment and the Rationale for Combined Molecular and Immune Targeted Therapy. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 18, 42.

- Gibney, G.T.; Weiner, L.M.; Atkins, M.B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e542–e551.

- Vivier, E.; Artis, D.; Colonna, M.; Diefenbach, A.; Di Santo, J.P.; Eberl, G.; Koyasu, S.; Locksley, R.M.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Mebius, R.E.; et al. Innate Lymphoid Cells: 10 Years On. Cell 2018, 174, 1054–1066.

- Chiossone, L.; Dumas, P.Y.; Vienne, M.; Vivier, E. Natural killer cells and other innate lymphoid cells in cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 671–688.

- Cristiani, C.M.; Garofalo, C.; Passacatini, L.C.; Carbone, E. New avenues for melanoma immunotherapy: Natural Killer cells? Scand. J. Immunol. 2020, 91, e12861.

- Garofalo, C.; De Marco, C.; Cristiani, C.M. NK Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment as New Potential Players Mediating Chemotherapy Effects in Metastatic Melanoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 754541.

- Cristiani, C.M.; Capone, M.; Garofalo, C.; Madonna, G.; Mallardo, D.; Tuffanelli, M.; Vanella, V.; Greco, M.; Foti, D.P.; Viglietto, G.; et al. Altered Frequencies and Functions of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Melanoma Patients Are Modulated by Immune Checkpoints Inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 811131.

- Salimi, M.; Wang, R.; Yao, X.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Chang, X.; Fan, P.; Dong, T.; Ogg, G. Activated innate lymphoid cell populations accumulate in human tumour tissues. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 341.

- Yu, Y.; Tsang, J.C.; Wang, C.; Clare, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Brandt, C.; Kane, L.; Campos, L.S.; Lu, L.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq identifies a PD-1hi ILC progenitor and defines its development pathway. Nature 2016, 539, 102–106.

- Seillet, C.; Mielke, L.A.; Amann-Zalcenstein, D.B.; Su, S.; Gao, J.; Almeida, F.F.; Shi, W.; Ritchie, M.E.; Naik, S.H.; Huntington, N.D.; et al. Deciphering the Innate Lymphoid Cell Transcriptional Program. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 436–447.

- Spits, H.; Cupedo, T. Innate lymphoid cells: Emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 647–675.

- Artis, D.; Spits, H. The biology of innate lymphoid cells. Nature 2015, 517, 293–301.

- Spits, H.; Bernink, J.H.; Lanier, L. NK cells and type 1 innate lymphoid cells: Partners in host defense. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 758–764.

- Fuchs, A.; Vermi, W.; Lee, J.S.; Lonardi, S.; Gilfillan, S.; Newberry, R.D.; Cella, M.; Colonna, M. Intraepithelial type 1 innate lymphoid cells are a unique subset of IL-12- and IL-15-responsive IFN-γ-producing cells. Immunity 2013, 38, 769–781.

- Bernink, J.H.; Krabbendam, L.; Germar, K.; de Jong, E.; Gronke, K.; Kofoed-Nielsen, M.; Munneke, J.M.; Hazenberg, M.D.; Villaudy, J.; Buskens, C.J.; et al. Interleukin-12 and -23 Control Plasticity of CD127(+) Group 1 and Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Intestinal Lamina Propria. Immunity 2015, 43, 146–160.

- Bernink, J.H.; Peters, C.P.; Munneke, M.; te Velde, A.A.; Meijer, S.L.; Weijer, K.; Hreggvidsdottir, H.S.; Heinsbroek, S.E.; Legrand, N.; Buskens, C.J.; et al. Human type 1 innate lymphoid cells accumulate in inflamed mucosal tissues. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 221–229.

- Ercolano, G.; Garcia-Garijo, A.; Salomé, B.; Gomez-Cadena, A.; Vanoni, G.; Mastelic-Gavillet, B.; Ianaro, A.; Speiser, D.E.; Romero, P.; Trabanelli, S.; et al. Immunosuppressive Mediators Impair Proinflammatory Innate Lymphoid Cell Function in Human Malignant Melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 556–564.

- Krabbendam, L.; Bernink, J.H.; Spits, H. Innate lymphoid cells: From helper to killer. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 68, 28–33.

- Moretti, S.; Chiarugi, A.; Semplici, F.; Salvi, A.; De Giorgi, V.; Fabbri, P.; Mazzoli, S. Serum imbalance of cytokines in melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2001, 11, 395–399.

- Silver, J.S.; Kearley, J.; Copenhaver, A.M.; Sanden, C.; Mori, M.; Yu, L.; Pritchard, G.H.; Berlin, A.A.; Hunter, C.A.; Bowler, R.; et al. Inflammatory triggers associated with exacerbations of COPD orchestrate plasticity of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 626–635.

- Ohne, Y.; Silver, J.S.; Thompson-Snipes, L.; Collet, M.A.; Blanck, J.P.; Cantarel, B.L.; Copenhaver, A.M.; Humbles, A.A.; Liu, Y.J. IL-1 is a critical regulator of group 2 innate lymphoid cell function and plasticity. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 646–655.

- Bal, S.M.; Bernink, J.H.; Nagasawa, M.; Groot, J.; Shikhagaie, M.M.; Golebski, K.; van Drunen, C.M.; Lutter, R.; Jonkers, R.E.; Hombrink, P.; et al. IL-1β, IL-4 and IL-12 control the fate of group 2 innate lymphoid cells in human airway inflammation in the lungs. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 636–645.

- Rethacker, L.; Roelens, M.; Bejar, C.; Maubec, E.; Moins-Teisserenc, H.; Caignard, A. Specific Patterns of Blood ILCs in Metastatic Melanoma Patients and Their Modulations in Response to Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1446.

- Tas, F.; Karabulut, S.; Yasasever, C.T.; Duranyildiz, D. Serum transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) levels have diagnostic, predictive, and possible prognostic roles in patients with melanoma. Tumour Biol. 2014, 35, 7233–7237.

- Gao, Y.; Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, F.; Bald, T.; Ng, S.S.; Young, A.; Ngiow, S.F.; Rautela, J.; Straube, J.; Waddell, N.; Blake, S.J.; et al. Tumor immunoevasion by the conversion of effector NK cells into type 1 innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 1004–1015.

- Cortez, V.S.; Ulland, T.K.; Cervantes-Barragan, L.; Bando, J.K.; Robinette, M.L.; Wang, Q.; White, A.J.; Gilfillan, S.; Cella, M.; Colonna, M. SMAD4 impedes the conversion of NK cells into ILC1-like cells by curtailing non-canonical TGF-β signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 995–1003.

- Hawke, L.G.; Mitchell, B.Z.; Ormiston, M.L. TGF-β and IL-15 Synergize through MAPK Pathways to Drive the Conversion of Human NK Cells to an Innate Lymphoid Cell 1-like Phenotype. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 3171–3181.

- Guia, S.; Fenis, A.; Vivier, E.; Narni-Mancinelli, E. Activating and inhibitory receptors expressed on innate lymphoid cells. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 331–341.

- Bernink, J.H.; Ohne, Y.; Teunissen, M.B.M.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Krabbendam, L.; Guntermann, C.; Volckmann, R.; Koster, J.; van Tol, S.; et al. c-Kit-positive ILC2s exhibit an ILC3-like signature that may contribute to IL-17-mediated pathologies. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 992–1003.

- Golebski, K.; Ros, X.R.; Nagasawa, M.; van Tol, S.; Heesters, B.A.; Aglmous, H.; Kradolfer, C.M.A.; Shikhagaie, M.M.; Seys, S.; Hellings, P.W.; et al. IL-1β, IL-23, and TGF-β drive plasticity of human ILC2s towards IL-17-producing ILCs in nasal inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2162.

- Trabanelli, S.; Chevalier, M.F.; Derré, L.; Jandus, C. The pro- and anti-tumor role of ILC2s. Semin. Immunol. 2019, 41, 101276.

- Wagner, M.; Ealey, K.N.; Tetsu, H.; Kiniwa, T.; Motomura, Y.; Moro, K.; Koyasu, S. Tumor-Derived Lactic Acid Contributes to the Paucity of Intratumoral ILC2s. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 2743–2757.e5.

- Jacquelot, N.; Seillet, C.; Wang, M.; Pizzolla, A.; Liao, Y.; Hediyeh-Zadeh, S.; Grisaru-Tal, S.; Louis, C.; Huang, Q.; Schreuder, J.; et al. Blockade of the co-inhibitory molecule PD-1 unleashes ILC2-dependent antitumor immunity in melanoma. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 851–864.

- Ikutani, M.; Yanagibashi, T.; Ogasawara, M.; Tsuneyama, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Hattori, Y.; Kouro, T.; Itakura, A.; Nagai, Y.; Takaki, S.; et al. Identification of innate IL-5-producing cells and their role in lung eosinophil regulation and antitumor immunity. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 703–713.

- Kim, J.; Kim, W.; Moon, U.J.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, H.J.; Sin, J.I.; Park, N.H.; Cho, H.R.; Kwon, B. Intratumorally Establishing Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Blocks Tumor Growth. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 2410–2423.

- Howard, E.; Hurrell, B.P.; Helou, D.G.; Quach, C.; Painter, J.D.; Shafiei-Jahani, P.; Fung, M.; Gill, P.S.; Soroosh, P.; Sharpe, A.H.; et al. PD-1 Blockade on Tumor Microenvironment-Resident ILC2s Promotes TNF-α Production and Restricts Progression of Metastatic Melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 733136.

- Long, A.; Dominguez, D.; Qin, L.; Chen, S.; Fan, J.; Zhang, M.; Fang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kuzel, T.M.; Zhang, B. Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells Impede IL-33-Mediated Tumor Suppression. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 3456–3464.

- Schuijs, M.J.; Png, S.; Richard, A.C.; Tsyben, A.; Hamm, G.; Stockis, J.; Garcia, C.; Pinaud, S.; Nicholls, A.; Ros, X.R.; et al. ILC2-driven innate immune checkpoint mechanism antagonizes NK cell antimetastatic function in the lung. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 998–1009.

- Lim, A.I.; Verrier, T.; Vosshenrich, C.A.; Di Santo, J.P. Developmental options and functional plasticity of innate lymphoid cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 44, 61–68.

- Bruchard, M.; Ghiringhelli, F. Deciphering the Roles of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 656.

- Viant, C.; Rankin, L.C.; Girard-Madoux, M.J.H.; Seillet, C.; Shi, W.; Smyth, M.J.; Bartholin, L.; Walzer, T.; Huntington, N.D.; Vivier, E.; et al. Transforming growth factor-β and Notch ligands act as opposing environmental cues in regulating the plasticity of type 3 innate lymphoid cells. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra46.

- Raykova, A.; Carrega, P.; Lehmann, F.M.; Ivanek, R.; Landtwing, V.; Quast, I.; Lünemann, J.D.; Finke, D.; Ferlazzo, G.; Chijioke, O.; et al. Interleukins 12 and 15 induce cytotoxicity and early NK-cell differentiation in type 3 innate lymphoid cells. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 2679–2691.

- Eisenring, M.; vom Berg, J.; Kristiansen, G.; Saller, E.; Becher, B. IL-12 initiates tumor rejection via lymphoid tissue-inducer cells bearing the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 1030–1038.

- Nussbaum, K.; Burkhard, S.H.; Ohs, I.; Mair, F.; Klose, C.S.N.; Arnold, S.J.; Diefenbach, A.; Tugues, S.; Becher, B. Tissue microenvironment dictates the fate and tumor-suppressive function of type 3 ILCs. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 2331–2347.

- Moskalenko, M.; Pan, M.; Fu, Y.; de Moll, E.H.; Hashimoto, D.; Mortha, A.; Leboeuf, M.; Jayaraman, P.; Bernardo, S.; Sikora, A.G.; et al. Requirement for innate immunity and CD90⁺ NK1.1⁻ lymphocytes to treat established melanoma with chemo-immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 296–304.

- Cristiani, C.M.; Turdo, A.; Ventura, V.; Apuzzo, T.; Capone, M.; Madonna, G.; Mallardo, D.; Garofalo, C.; Giovannone, E.D.; Grimaldi, A.M.; et al. Accumulation of Circulating CCR7+ Natural Killer Cells Marks Melanoma Evolution and Reveals a CCL19-Dependent Metastatic Pathway. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 841–852.

- Pober, S.J. Endothelial activation: Intracellular signaling pathways. Arthritis Res. 2002, 4 Suppl 3, S109–S116.

- Shields, J.D.; Kourtis, I.C.; Tomei, A.A.; Roberts, J.M.; Swartz, M.A. Induction of lymphoidlike stroma and immune escape by tumors that express the chemokine CCL21. Science 2010, 328, 749–752.