Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Pediatrics

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, the actual treatment for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, is essential in children with cystic fibrosis to prevent malabsorption and malnutrition and needs to be urgently initiated. This therapy presents many considerations for physicians, patients, and their families, including types and timing of administration, dose monitoring, and therapy failures. Based on clinical trials, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy is considered effective and well-tolerated in children with cystic fibrosis.

- pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

- cystic fibrosis

- exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is one of the most severe and prevalent multisystemic genetic diseases with significant morbidity, especially pulmonary and pancreatic. Chronic lung disease, excessive sweat electrolytes losses, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and malnutrition are the most common morbidities.

Although it is predominantly a lung disease displaying chronic inflammation and infection, 85% of patients have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI), with significant consequences on nutritional status and a substantial impact on survival. According to the European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry (ECFSPR) 254 patients were registered in Romania in 2020, 94.42% being children. 73% of these patients were diagnosed at the age < 1 year. The average age at diagnosis was 1.47 years [1].

CF is a monogenic, autosomal recessive disorder with highly variable and complex clinical manifestations due to two mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that is situated on the long arm of chromosome 7 and contains 27 exons [2,3].

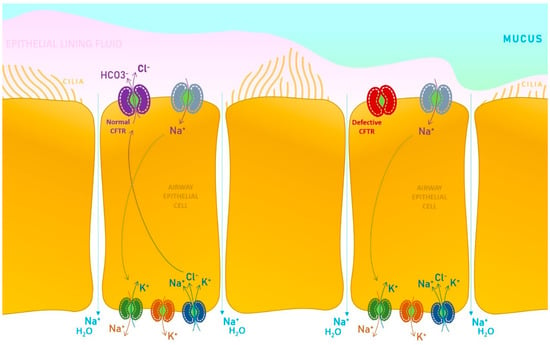

There are over 2000 mutations with varying functional consequences [4]. The CF gene encodes the CFTR protein. This protein has five domains, two membrane-spanning domains (MSDs), two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs), and a regulatory domain (R), which acts like a phosphorylation site. On a more detailed view of its role, we find CFTR physiologically expressed on the surface of airway epithelial cells, having a regulatory role considering the chloride ion channel. Consequently to the mutations, the CFTR defective function is reflected upon the impaired transport of chloride (Cl−) and bicarbonate (HCO3−) ions, also limiting the water molecules permeation, encouraging the buildup of mucus at this level, conducting to airway blockage, pathogenic agents accumulation, leading to inflammatory events and infections persistence, irreversibly damaging the lungs, in a relatively short period of time.

Basically, the mucus mobility imprinted by the ciliary domains is affected by the dehydration phenomenon, the bacterial removal and the existence of a sufficient volume of surface liquid are dramatically influenced by the abnormal flow of chloride and bicarbonate ions, and nevertheless, the pH of the fluid is essentially acidic due to the ionic trafficking defect.

The increased viscosity is clinically transposed to airways obstruction, followed by pathogens colonization, triggering infection and inflammation, all resulting shortly in an impaired respiratory process, even severe respiratory failure. This mechanism depicted at the level of the airway epithelial cell develops similarly in other epithelial cells of exocrine glands, e.g., the pancreas [5,6,7].

In a healthy state, the physiologic water content of the airway surface liquid is maintained by a subsequent mechanism facilitated by the absorption of sodium (Na+) ions through a dedicated channel (epithelial Na+ channel), exiting the cell by the basolateral Na+-K+ pump. Chloride ions enter the cell by the basolateral Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and are excreted mainly through the CFTR protein present at the surface of the apical membrane level, which functions as a chloride channel. Secondary, there are also calcium-activated Cl− channels that may partially depurate the chloride from the cell. Considering all the trafficking mechanisms presented, the CFTR physiologic expression and functioning is critical for all other channels that assure a normal electrolytic exchange and a regulatory pathway in the context of secretory tissues (Figure 1).

CFTR protein functions as a chloride and bicarbonate ion channel on the apical membrane of the epithelial cells of exocrine glands. This chloride channel is activated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [10,11,12].

Defective CFTR results in lower pH of ductal secretion due to reduced bicarbonate buffering, a lower volume, and increased viscosity of digestive and pulmonary secretions. The results are EPI (secondary to duct obstruction with reduced delivery of digestive enzymes to the intestines and impaired absorption of key nutrients) and obstructive lung disease (secondary to abnormally viscous and elastic mucus, that is a hallmark of pulmonary disease, leading to decreased mucociliary clearance, and increased risk for inflammation and infection). CF also determines impairing function of other organs such as the liver, gallbladder and intestines [13,14,15].

Considering that CF is associated with EPI, a common complication of the disease, it suggests that CFTR function has an important role in pancreas physiology [16] and this may be an argument for improving pancreatic function in patients who received CFTR modulators. The effects of these new therapies on pancreatic manifestations are not completely understood yet.

Some recent studies noticed that advances in CF treatment (i.e., CFTR modulators) facilitate a partial restoration of pancreatic function, the underlying mechanism remaining unclear [17]. Pancreatic dysfunction in CF results from ductal obstruction occurring early in life, even in utero [18]. Although the classical theory says that the pancreas is irreversibly damaged in this disease, modulator treatments could have a positive effect on pancreatic function. EPI refers to inadequate production of pancreatic enzymes, bicarbonate, and fluid, which leads to maldigestion and malabsorption.

PERT is the treatment for CF patients that also develop EPI. It is recommended to initiate PERT if there is a strong clinical suspicion of EPI (growth failure, gastrointestinal symptoms, steatorrhea, patients with two CFTR gene mutations associated with EPI) or if EPI is proven by laboratory evidence (fecal elastase less than 200 mcg/g, increased fecal fat, etc.). In general, PERT is administrated at the beginning of the meals, but some clinicians prefer the administration at halfway of the meal. Using PERT after a meal is not as effective.

PERT dose depends on the patient weight or dietary fat intake. For children younger than four years, the starting dose is 1000 lipase units/kg body weight/meal. Children older than 4 years start with 500 lipase units/kg body weight/meal. For infants and tube-feeding children we use the fat-based method. This method recommends the starting dose at approximately 1600 units lipase/g of fat taken per day. The most common causes for PERT failure are inadequate doses and treatment non-compliance (does not respect the timing of doses in relation to meals, the patient forgets to take PERT). If the dose of PERT is more than 10,000 lipase units/kg body weight/day there is a high risk for fibrosing colonopathy. Other side effects are dizziness, abdominal pain, flatulence and perianal rash. Pancreatic enzyme therapy is effective and generally well tolerated by pediatric patients with CF.

Despite significant advances in CF treatment, such as better control of chronic pulmonary infections, accessibility of new therapies, including CFTR modulators, aggressive nutritional supplementation with pancreatic enzymes, and lung transplantation, CF remains a progressive, lethal disease [19].

2. Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency in Children with Cystic Fibrosis

A normal functioning pancreas secrets into the duodenum digestive enzymes and bicarbonate for digestion of macronutrients like protein, fats, and starch. CF is the most common cause of EPI in the children population. 80 to 90% of patients diagnosed with CF have EPI [20,21]. According to ECFSPR—Annual Data Report 2020, the percentage of patients from Romania who were pancreatic insufficient and received pancreatic enzyme was 98% [1].

In EPI, due to CF, pancreatic digestive enzyme secretion is severely decreased, and the amount of bicarbonate is reduced due to obstruction of pancreatic ducts and abnormal secretion. The pancreas of children with CF and EPI is shrunken, with significant fibrosis, cysts, and fatty replacement. Studies showed that pancreatic small duct obstruction starts in utero, in the second trimester of gestation.

The genotype of children with CF is highly predictive of pancreatic function, the grades of EPI being closely correlated with type of mutation. Children with a minimum of one mutation from class V or IV CFTR defects (considered mild mutations) are almost always pancreatic sufficient. By contrast, severe mutations like mutations from class I, II, and III are associated with pancreatic insufficiency [22,23]. In their study, Walkowiak et al., demonstrated that the genotype of a CF patient is strongly linked with the probability of developing exocrine pancreatic insufficiency but not always the presence of a mild mutation excludes pancreatic insufficiency [23]. Insufficient pancreatic patients must immediately initiate standard therapy with pancreatic enzymes.

3. Clinical Considerations of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency

3.1. Presentation

When the pancreas does not produce physiologic amounts of digestive enzymes results in fats, proteins, and carbohydrates malabsorption. Clinically, patients may manifest malnutrition, poor weight gain or weight loss, and gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal distension, steatorrhea, abdominal pain, flatulence, diarrhea, and rectal prolapse. Also, when fats aren’t adequately digested, there is an important risk of constipation or other severe complications like distal intestinal obstruction syndrome.

3.2. Diagnosis

There are direct and indirect methods for testing exocrine pancreatic function. In the pediatric population, direct tests are unsuitable because they require endoscopy, an expensive and invasive procedure. However, their high specificity and sensitivity are considered the gold standard for evaluating exocrine pancreatic function. A direct method for assessing the exocrine pancreatic function is performing a secretin-cholecystokinin stimulation test. Direct tests measure the amount of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate secreted. Indirect tests are more frequently used than direct tests because they are non-invasive, less expensive, and require less time. They evaluate the effect due to the lack of an enzyme [24,25,26,27].

The most used indirect test is faecal elastase because it is easy to perform, is rapid compared to coefficient of fat absorption (CFA) or faecal chymotrypsin, evaluates the need for PERT, and is more specific and sensitive compared with faecal chymotrypsin and lipase [27,28,29]. Unlike faecal chymotrypsin and faecal lipase, stool elastase does not require discontinuation of PERT before dosing, does not require special storage, and one stool sample is enough for the assessment. Patients with CF and EPI usually have levels < 15 mcg/g stool of faecal elastase.

Healthy people have faecal elastase >200 mcg/g stool (usually >500). Severe pancreatic insufficiency is diagnosed when faecal elastase <100 mcg/g stool, and mild/moderate pancreatic insufficiency is between 100–200 mcg/g stool [30]. Patients who are pancreatic sufficient at diagnosis need periodic assessment due to the risk of becoming pancreatic insufficient by age.

3.3. Malnutrition in CF

Undernutrition is strongly associated with CF and is correlated with genetic factors (i.e., mutations) and with other factors, such as higher energy needs (120–150% of normal requirements), energy losses, and decreased nutrient intake and absorption. CF patients have an increased basal energy expenditure resulting from chronic pulmonary infections and breathing efforts. Although improved nutritional status was observed in the last 2 decades, adequate nutrition remains an important issue. Children with CF associate a poor nutritional status that leads to declined lung function and increased mortality.

Patients that were early diagnosed through newborn screening programs received an early nutritional therapeutic intervention, and thus, they could have a positive nutritional outcome [31]. Newborn screening for CF became widely available in the last few years. According to European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry (ECFSPR), Annual Data Report 2020, 79% of children of 5 years old or younger, who were registered in 2020, were screened at birth. However, Romania has no neonatal screening program for CF yet, consequently, only 9% of patients registered in 2020 were screened at birth [1]. In the absence of this program, for an early diagnosis, the best screening procedure is a careful monitoring of growth, a detailed medical history, and a physical exam.

Three conditions contribute to malnutrition in CF patients: energy losses, high-energy needs, and inadequate nutrient intake. The essential cause of energy loss is represented by maldigestion/malabsorption due to EPI. Energy needs are higher in CF patients with pancreatic insufficiency than in healthy individuals. High-energy expenditure seems to be correlated with pancreatic insufficiency. High-energy requirements are associated with lung inflammation and infection. Basic nutritional care includes a high-calorie, high-fat diet associated with PERT, and fat-soluble vitamins supplementation. Morbidities like pulmonary infections, gastrointestinal complication (gastro-esophageal reflux, constipation, distal intestinal obstructive syndrome) can decrease appetite and determine inadequate nutrient intake [31,32,33].

Other complications of CF are represented by a CF-related diabetes, that could determine and worsen malnutrition and CF-related liver disease which associates specific nutritional deficiencies (fat-soluble vitamins, essential fatty acid, calcium), that can lead to osteopenia and osteoporosis [34,35,36,37].

Considering the consequences of nutritional deficiencies in children with CF it is recommended an early and sustained nutritional therapy, to obtain adequate growth, similar to that of same-aged non-CF patients. Patients with body mass index (BMI) values below 25th percentile have been considered nutritionally “at risk”. According to the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Cystic Fibrosis Society (ECFS) guidelines on nutrition care for children below 2 years of age are recommended both weight and length for age percentiles to assess the nutritional status, and the aim is achieving the 50th percentile. For children above 2 years, and adolescents (2–18 years) are recommended regular assessment of weight, length and BMI, and the goal is achieving 50th percentile for healthy children [38]. In Romania the median z-score for BMI for children 2 to 17 years registered in 2020 was −1 (meaning that 50% of the patients are below of this z-score for BMI). The percentage of children underweight (z-score < −2) for patients 2 to 17 years was 20% for the female sex, and 18% for male patients [1]. BMI is used to evaluate nutritional status, but it has limitations because it could not differentiate fat mass from lean body mass (LBM). Another 2 indicators of nutritional deficiency are more sensitive than BMI: LBM and bone mineral content (BMC), lower values being associated with impaired pulmonary function in children [39,40]. BMI fails to assess body composition, especially fat free mass, an important indicator of nutritional status. Lower values for fat free mass were associated with decreased pulmonary function and undernutrition. Also, pulmonary chronic infection, a characteristic of this disease has been linked to decreased fat free mass [41,42]. The predictive value of body composition for clinical outcomes of CF patients is still undefined [43]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing in the last years, among adult patients with CF [44,45].

Research suggests that CFTR modulators may increase weight in CF patients, the underlying mechanism being multifactorial (improved pancreatic exocrine function, increased calorie intake, and nutrient absorption, decreased energy expenditure due to improved pulmonary function) [34,46,47].

According to Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) Patient Registry—annual data report 2020, 40.4% of adult patients are overweight (28.7%) or obese (11.7%), with a high prevalence in men. This percentage has more than doubled in the past 20 years (15.3% in 2001) [48].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pharmaceutics15010162

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!