Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Engineering, Petroleum

Waste or used cooking oil (WCO/UCO) is a common source of trans fat consumed by Indians, leading to many non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, cancer, etc. In fact, out of 230 million MT of edible oil consumption, India is currently capable of producing only 3 million MT of biodiesel. Moreover, with the increased emphasis on the circular economy to improve rural employment opportunities, India should adopt a complete exergy analysis of biodiesel production from WCO.

- waste cooking oil

- biodiesel

- circular economy

- economic analysis

1. Introduction

Waste or used cooking oil (WCO/UCO) is a common source of trans fat consumed by Indians, leading to many non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, stroke, cancer, etc. [1]. Although many medical practitioners have cautioned about the harmful effects of WCO, its usage has been found to be increasing, mainly due to the volatile pricing of imported cooking oil in India. It was found out that nearly 60% of the national oil consumption is met by importing WCO, and it is priced dubiously, influencing consumers to reuse the oil repeatedly [2]. However, this WCO could be used to efficiently and effectively replace feedstock in a biodiesel plant. WCO as a feedstock offers the twin advantages of breaking the food supply chain that is causing harmful diseases and providing a cheaper alternative to the growing demands of fossil fuels. Also, using WCO as a feedstock helps to reduce the production cost of biodiesel [3]. Various other benefits like lower dependence on fossil fuels, improved environmental quality, and an additional source of income for small food vendors are also reported by many researchers while using WCO as a feedstock for biodiesel production [4,5,6]. Many nations are setting a target of meeting their 10 to 20% transportation fuel needs through the use of WCO-based biodiesel to their advantage [7]. The Indian government is also intending to collect 5% of its edible oil consumption as a feedstock for biodiesel production, according to its recent biofuel policy [8,9].

Circular Economy—An Incentive to Use WCO as a Feedstock

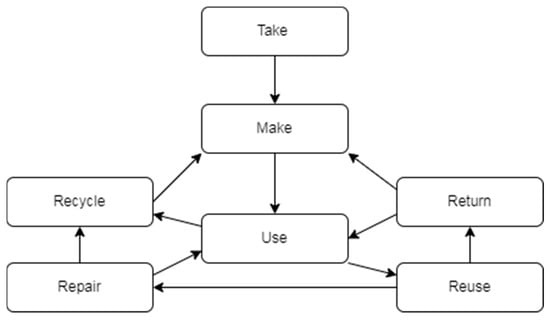

Even with all these advantages, the collection of WCO comes with many problems, and as a result, many countries have developed their own regulatory and incentive-based collection mechanisms. In general, there are two types of WCO collection mechanisms: 1. biodiesel enterprise takeback (BET), and 2. third-party takeback (TPT). Most of the successful WCO recovery countries, like the United States of America and Japan, follow the TPT mechanism, and other countries like China, Brazil, etc., follow the BET mechanism with some modifications to suit their specific conditions [3]. India, too, developed a unique circular economy model (Figure 1) for WCO collection from different sources. India consumes the third largest amount of edible vegetable oil (over 24,660 ML per annum) in the world. Of that total, 40% of the oil is consumed by commercial food and beverage operators (FBO) and the remaining 60% by domestic households. Although the huge potential of over 15% of the oil consumption is there for biodiesel production, due to the lack of an effective supply chain and enforced collection mechanism, only 0.133% of the WCO is collected. This vast gap forced the various stakeholders of the Indian government to formulate and release a determined biofuel policy in the year 2018. In addition, the Goods and Services Tax imposed on biodiesel was reduced from 12% to 5% to increase the use of WCO as a feedstock [10].

Figure 1. Circular economy for WCO Collection.

Recent research on pricing WCO-based biodiesel also encourages the move to consider WCO as an important feedstock for biodiesel production. It was reported that nearly 60% to 70% of the production cost will be reduced in comparison to the use of vegetable edible or non-edible oils [11,12,13].

2. Suitability of WCO as a Feedstock for Biodiesel Production

In order to overcome the difficulties associated with depleting fossil fuel resources, biodiesel offers an excellent alternative, as it is produced from renewable feedstocks such as vegetable edible oils, WCO, or non-edible vegetable oils like Jatropha, among others. Biodiesel is a mono alkyl ester of long-chain fatty acids produced from renewable feedstocks [4].

2.1. WCO as a Feedstock for Biodiesel Production to Address Social Challenges

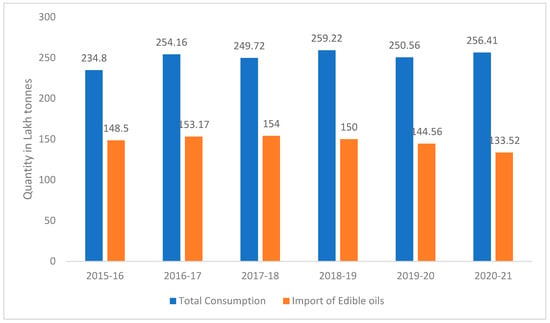

Although medical professionals have cautioned that the Indians are consuming 20% more than the world per capita average of edible oils, the increasing trend is likely to continue, and it was found to be 19 kg per annum. This rising demand is met by importing edible oils after spending about 40% of the total agricultural imports bill, making biodiesel production from edible vegetable seeds unethical [14,15]. However, the import of edible oils has been predominant even in recent years (Figure 2). Moreover, the availability of wasteland and water resources for the cultivation of non-edible vegetable feedstocks poses a considerable problem, leaving WCO as the only sustainable option for biodiesel production. Nevertheless, the safe disposal of WCO is an added advantage for using it as a feedstock. Most often, WCO is not disposed of but used until the last drop, leaving the consumers with several health hazards. Especially, WCO in big commercial food establishments is sold to small eateries and used in household applications which amount to nearly 60% of the total edible oil consumption. Due to this, it was evident that consumers contracted many non-communicable diseases like cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and organ failure. Therefore, WCO could be an excellent option for biodiesel production [1].

Figure 2. Total annual consumption and import of edible oil.

2.2. WCO as a Feedstock for Biodiesel Production to Address Technological Challenges

Up to 20% of biodiesel blended with diesel does not require engine modifications and results in better emission quality than petrol–diesel engines [11]. Several studies indicate that the use of WCO biodiesel resulted in reduced emission of particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrocarbons (HC) [16,17,18,19].

Especially in India, environmentally sustainable fuel is essential for the growing transport sector, whose conventional diesel consumption is predicted to reach 132 MKL, resulting in nearly 3 times the CO2 production [7]. Although the pour point of the biofuel-blended diesel will be increased, researchers have demonstrated that the addition of suitable bioadditives solves this problem [19].

2.3. WCO as a Feedstock in Biodiesel Production to Address Economical Challenges

India’s transport sector requires about 132 MKL of diesel and contributes 6.7% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP), with nearly 81% of the crude demand being met by imports. With the Indian government target of 5% of blending with biodiesel, WCO can be a perfect alternative, with the potential to save 10% of the import costs of INR 10,000 crores (INR 100 billion) [9].

Many recent research findings have contributed to the fact that WCO is an essential feedstock for biodiesel production, especially in isolated rural locations with a shortage of conventional fuel supply facilities. Collection of WCO paves the way for additional income to many collectors involved in the WCO biodiesel supply chain [11,20]. Furthermore, this collection of WCO could very well augment the Indian government’s Biofuel Policy 2018 and National Mission on Edible Oils—Oil Palm 2021 as a suitable alternative in the biodiesel supply chain [15].

Poverty reduction through income generation for a low-skilled population is also reported in many works concerning WCO collection through community collectors [19,20,21,22]. One of the biggest challenges in the WCO biodiesel supply chain is the collection, which is well addressed by recent research on circular economies. Many issues like seasonal variation of feedstock, availability of appropriate volume of feedstock for transportation, and real-time information could be easily solved using this circular economy model (Figure 1) [23].

3. Overview of WCO Collection Mechanisms

A recent study on biofuel feedstock reveals that China, Japan, and Korea use WCO as a major feedstock for biodiesel production [24]. However, in India, WCO is little-used as a feedstock for biodiesel production, with a contribution of 0.133% against the set target of 5% of conventional diesel fuel. Therefore, a country like India must study the best practices of those countries like Brazil, China, Japan, the United States, and Korea pertaining to collection methods [10]. Margarida Ribau Teixeira et al. (2018) [25] reported that out of WCO production from 23 countries, India’s per capita WCO production is abysmally deficient [26].

Several studies indicated that the collection of WCO from usage sectors is the major hindrance in using it as a feedstock in the biodiesel production chain [11,26]. It was reported in recent research that WCO-based biodiesel forms an essential component in meeting the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), especially 2 (Zero Hunger), 3 (Good Health), 11 (Sustainable cities and communities), and 13 (Climate action) [27]. In order to obtain a positive image among the nations, many countries have formulated several incentive policies to collect WCO from their food supply chains.

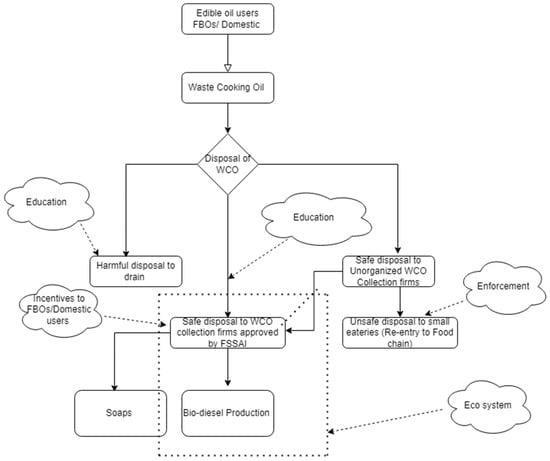

India at present adopts a strategy of education, enforcement, and ecosystem (EEE) for collecting WCO from households and FBOs. Considering the growing urbanisation and younger demographic advantage, this strategy is appropriate. However, the implementation of stricter rules and regulations at the grassroots level by enforcing agencies like the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) and the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas are found to be ineffective [2]. India should adopt an incentive-based approach similar to that of the developed nations mentioned above to increase WCO collection. Initiatives like eat-right campus awards among educational institutions effectively educate the student population about the harmful effects of reusing WCO in the food chain. This rating should be made mandatory for all accreditations of educational institutions [40,41].

The FSSAI should also consider enforcing stricter regulations for FBOs consuming less than 50 litres/day. In addition, they should adopt a health rating for FBOs as an essential prerequisite for licence approval [42]. Various studies have elucidated that the disbursal of incentives to restaurants and households for depositing WCO is highly effective in its collection [43,44,45,46]. Regarding a suitable ecosystem for better WCO collection, it was reported in the research literature that small FBOs, especially roadside food vendors, due to a lack of storage space and inadequate filtering equipment, do not submit their WCO and often drain it into sewer lines [2,46].

However, if suitable incentives had been given to the biodiesel producers instead of the recyclers, WCO collection would have improved [35]. For example, with the participation of biodiesel-producing companies, local FBOs, and local FSSAI officials, Madurai, a city in India, was able to collect 30 tonnes of WCO in the year 2020, out of which nearly 70% was used for biodiesel production [47]. Similar WCO collection models could be extended to all the cities of India. India should also think about providing such incentives to household consumers and FBOs. Based on the above SWOC analysis, the researchers recommend the following model (Figure 3) for enhanced WCO collection.

Figure 3. Recommended WCO collection model based on the SWOC analysis from the information RUCO [10].

4. WCO-to-Biodiesel Conversion Technologies

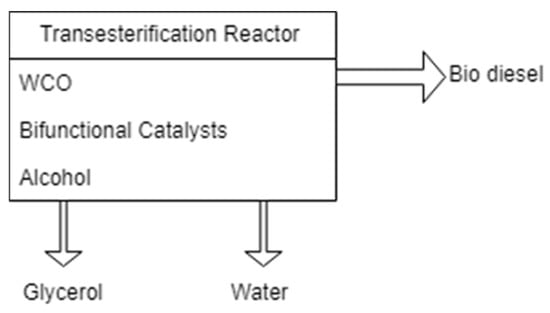

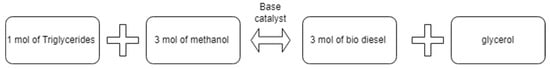

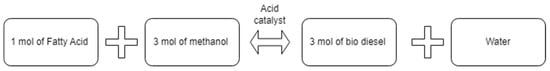

Many conversion technologies are available for turning WCO into biodiesel, like hydrotreating, gasification, pyrolysis, and transesterification [18]. However, Tabatabaei et al. [48] reported that the transesterification technique is the most economical and environment-friendly conversion method for biodiesel production from WCO after comprehensively reviewing all the conversion technologies. Transesterification is the process of fatty acid or vegetable oil reaction in the presence of a monohydric alcohol, catalysts, and heat over a period of time (Figure 4) [49,50,51].

Figure 4. Schematic of the transesterification process with bifunctional catalysts.

As a competitive conversion technology, the advantages of the transesterification process are presented in (Table 1).

Table 1. Competitiveness of transesterification process for WCO biodiesel production.

| Competitiveness | Reference |

|---|---|

| Eco-friendly | [48] |

| Increased volatility and reduced viscosity, molecular weight, flash point, and pour point | [52] |

| Requires no engine modification | [4,53] |

| Better biodegradability, combustion efficiency, and lubricity; higher cetane number; and lower sulphur and aromatic content compared to conventional diesel | [54,55,56] |

| Lower hydrocarbon, particulate matter, and unburnt carbon emissions | [57,58] |

| Lower stress on the environment and food security | [59] |

| Low-cost feedstock with higher yield | [60] |

| Wide choice of catalysts for better yield | [61] |

| Suitable for catalytic hydrotreating to improve the storage stability | [62] |

Even with these advantages, several studies reported limitations of the transesterification process for WCO biodiesel conversion due to its high FFA content. Generally, oils having greater than 1% content of FFAs are not suitable for transesterification using basic catalysts. Without pre-treatment, the biodiesel yield will be drastically reduced because of the saponification effect. However, these pre-treatment processes are expensive and time-consuming and need to be replaced with methods using more effective heterogeneous solid bifunctional catalysts [49,63,64,65,66].

Traditionally, homogeneous catalysts such as KOH, NaOH, potassium methoxide, and sodium methoxide are used for biodiesel conversion due to their ability to facilitate the transesterification reaction at relatively very low temperatures and high reaction rates over 4000 times faster than acid catalysts. Even with all these advantages, these homogeneous base catalysts’ transesterification processes are suitable only for oils with less than 1% FFA content, i.e., food-grade oils. WCO conversion to biodiesel using these catalysts requires the reduction of FFAs by several pre-treatment processes. In addition, the biodiesel yield will be low due to high FFA content and impurities in the WCO [67,68].

Recently, researchers demonstrated that using heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel conversion eliminates the costlier post-reaction washing problems, resulting in better biodiesel yield. Because these heterogeneous catalysts are in a different state (solid), the reacting medium can easily be separated effectively from the post-reaction mixture by filtration and centrifuging. In addition, these separated solid catalysts can be reused, thus making the biodiesel conversion process a more economical one. In addition to this, the quality of biodiesel produced from the solid catalysts is very good due to the lower level of dissolved metals and other elements. However, even with all these advantages, the use of heterogeneous catalysts is limited in industry because of the following issues: severe reaction condition requirements [69], slower reaction rate due to the mass transfer resistance [70], solid base catalysts being suitable only for oils with up to 3% FFA content under mild reaction conditions [71], and heterogeneous acid catalysts requiring higher temperature and more reaction time for converting WCO [72].

Therefore, recent research on biodiesel production techniques has focused on using heterogeneous bifunctional catalysts to accomplish transesterifying triglycerides and esterifying FFAs simultaneously under moderate reaction conditions. These bifunctional catalysts are found to be best suited for biodiesel production from WCO, even with their high FFA content and moisture content (Figure 5 and Figure 6) [73,74,75].

Figure 5. Transesterification reaction of biodiesel from triglycerides.

Figure 6. Esterification reaction of biodiesel from fatty acids.

5. Techno-Economic Analysis of WCO Based Biodiesel

One of the chief advantages of WCO biodiesel is its contribution to the circular economy and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The circular economy focuses on adding higher value to the recycling of low-cost bioresidues in a sustainable and environmentally friendly way. This unique advantage attracts many nations to adopt the production of WCO biodiesel. Additionally, the safe disposal and health benefits associated with terminating WCO in the food supply chain motivate countries to adopt WCO biodiesel production. However, many researchers pointed out that the collection and pre-treatment of WCO prior to transesterification involve many environmental issues. Especially, the energy and chemicals used in the pre-treatment process might affect the sustainability of WCO biodiesel production [27,77,78,79,80,81].

Various researchers ascertained that life cycle assessment (LCA) should be carried out to study WCO biodiesel’s impact on socio-economic and environmental concerns. For any product or process to be viable, it is necessary to analyse its full impact on the environment using a knowledge-based decision support system like LCA. The LCA model for a WCO biodiesel often focuses on mass and energy balance parameters. LCA mandatorily includes all the products (mass) and all the work and heat energy required for the transformation of WCO into biodiesel, along with their complete impact on the environment. Such an LCA analysis focuses on the transformation process and the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to evaluate the method’s effectiveness in meeting the SDGs prescribed by the United Nations. For its member countries, especially India, which aspires to balance economic growth and environmental impact assessment, these LCA studies on WCO biodiesel are highly useful in finding the best fuel mix of biofuel and fossil fuel [82,83,84,85,86].

Ideally, any techno-economic analysis of a process or product should offer solutions to technical and economic problems to make that particular product or process profitable and sustainable. However, similar assessments performed on WCO biodiesel often lack clarity on the part of environmental emissions, resource starvation, and thermodynamic aspects because of the uncertainties associated with the collection of WCO. Therefore, an exhaustive LCA should focus on energy analysis as well as exergy analysis to arrive at an informed decision on WCO biodiesel production by evaluating different processes from the environmental sustainability perspective [3,87,88,89].

Many studies are available on energy analysis of WCO biodiesel production in India, but an exhaustive energy and exergy analysis covering the entire spectrum of India is the need of the hour. This is more important considering that the collection and production techniques of WCO in India vary drastically compared to other countries. The lack of uniformity in the policy of WCO collection and pricing of biodiesel, lack of conclusive prior data available on energy, and lack of cost analysis of biodiesel production make an LCA study a difficult proposition [3,10,90]. However, with the maturity level of the transesterification process, India can use other countries’ energy and cost analyses without any loss of accuracy.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/en16041739

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!