Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Ophthalmology

Glaucoma is a multifactorial neurodegenerative illness requiring early diagnosis and strict monitoring of the disease progression. Artificial intelligence algorithms can extract various optic disc features and automatically detect glaucoma from fundus photographs.

- biomarkers

- artificial intelligence

- genetics

1. Artificial Intelligence in Glaucoma

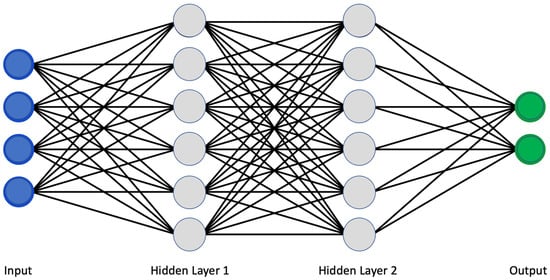

The use of artificial intelligence is expanding rapidly. Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) allowed a more sophisticated and self-programming way to use machines in automatic data analysis. More in detail, in machine learning, a system can automatically improve its performance and learn by itself with experience without being specifically programmed to do so. Specifically, using a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture, the deep learning algorithm can take in an input image, assign importance (learnable weights and biases) to various aspects/objects in the image, and be able to differentiate one from the other [5]. Similar to neurons derived from the mammalian visual cortex, the neural network’s architecture consists of many hidden layers, each with its specific receptive field and connection to a further layer (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classical scheme of a convolutional neural network.

The deep learning network works as a two-step process. The first is the feature learning step, in which convolution, pooling, and activation functions make the ‘jump ahead’ between hidden layers. Secondly, the classification function converts the probability value to a label, providing a clinical output such as healthy or pathologic [6,7].

Although this architecture traditionally provided a high degree of computational power, in recent years, more advanced network architectures have been developed, allowing the system to analyze more complex data sources. AlexNet (2012) was introduced to improve the results of the ImageNet challenge. VGGNet (2014) was introduced to reduce the number of parameters in the CNN layers and improve the training time. ResNet (2015) architecture makes use of shortcut connections to solve the vanishing gradient problem (which is encountered when during the iteration of training, each of the neural network’s weights receives an update proportional to the partial derivative of the error function with respect to the current weight) [8]. The basic building block of ResNet is a residual block that is repeated throughout the network. There are multiple versions of ResNet architectures, each with a different number of layers. Inception (2014) increases the network space from which the best network is to be chosen via training. Each inception module can capture salient features at different levels [9].

Traditional metrics assessing the DL algorithm’s quality are sensitivity, specificity, precision, accuracy, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and area under the receiver operating curve (AUC).

It is known that the early detection of glaucoma could eventually preserve vision in affected people. However, due to its clinical history of being symptomatic only in advanced stages and when most of the RGCs are already compromised, it is crucial to introduce a tool to detect glaucoma in clinical practice in pre-symptomatic form automatically. Furthermore, it could be of clinical relevance also to find new ways to provide targeted treatment and forecast the clinical progression.

2. Fundus Photography

In clinical practice, ophthalmologists suspect glaucoma by analyzing optic nerve head (ONH) anatomy, cup-to-disc ratio (CDR), optic nerve head notching or vertical elongation, retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thinning, presence of disc hemorrhages, nasal shifting of vessels, or the presence of parapapillary atrophy. However, the diagnostic process could be challenging considering the extreme variance of these parameters [10]. It has been shown that agreement among experts on detecting glaucoma from optic nerve anatomy is barely moderate [11]. Furthermore, with standard fundus photography, not only the variability of anatomy could be misleading, but also the parameters of acquisition such as exposition, focus, depth of focus, contrast, quality, magnification, and state of mydriasis.

In this scenario, artificial intelligence algorithms can extract various optic disc features and automatically detect glaucoma from fundus photographs. For example, Ting et al. [7] collected 197,085 images and trained an artificial intelligence algorithm to automatically determine the cup-disc ratio (CDR) with an AUC of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.942 and sensibility and specificity, respectively, of 0.964 and 0.872. Similarly, Li et al. [12] developed an algorithm based on 48,116 fundus images reporting high sensitivity (95.6%), specificity (92.0%), and AUC (0.986). Although the importance of automatically detecting the excavation of the optic nerve head, it is known that high inter-subject variability characterizes CDR; some large optic nerve heads have bigger cupping even without any sign of glaucoma. To reduce the rate of false positives, other researchers trained a deep learning algorithm to determine the presence of glaucoma based on fundus photographs and implemented it with the visual field severity [13].

Li and coworkers used a pre-trained CNN called ResNet101 and implemented it with raw clinical data in the last connected layer of the network; interestingly, there were no statistically significant changes in AUC, but they found an improvement in the overall sensitivity and specificity of the model, confirming the importance of multi-source data to improve the discriminative capacity of the glaucomatous optic disc [14].

More recently, Hemelings et al. utilized a pre-trained CNN structure relying on active and transfer learning to develop an algorithm with an AUC of 0.995. They also introduced the possibility for clinicians to use heatmaps and occlusion tests to understand better the predominant areas from which the algorithm based its predictions; it is an exciting way of trying to overcome some problems related to the well-known ‘black-box’ effect [15].

The majority of the publications that were analyzed suggested that an automated system for diagnosing glaucoma could be developed (Table 1). The severity of the disease and its high incidence rates support the studies that have been conducted. Deep learning and other recent computational methods have proven to be promising fundus imaging technologies. Some recent technologies, such as data augmentation and transfer learning, have been used as an alternative way to optimize and reduce network training, even though such techniques necessitate a large database and high computational costs.

Table 1. Summary of studies on glaucoma detection using fundus photography.

| Author | Year | N. of Images | Structure | SEN | SPEC | ACC | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolar et al. [16] | 2008 | 30 | FD | 93.80% | |||

| Nayak et al. [17] | 2009 | 61 | Morphological | 100% | 80% | 90% | |

| Bock et al. [18] | 2010 | 575 | Glaucoma Risk Index | 73% | 85% | 80% | |

| Acharya et al. [19] | 2011 | 60 | SVM | 91% | |||

| Dua et al. [20] | 2012 | 60 | DWT | 93.3% | |||

| Mookiah et al. [21] | 2012 | 60 | DWT, HOS | 86.7% | 93.3% | 93.3% | |

| Noronha et al. [22] | 2014 | 272 | Higher order cumulant features | 100% | 92% | 92.6% | |

| Acharya et al. [23] | 2015 | 510 | Gabor transform | 89.7% | 96.2% | 93.1% | |

| Isaac et al. [24] | 2015 | 67 | Cropped input image after segmentation | 100% | 90% | 94.1% | |

| Raja et al. [25] | 2015 | 158 | Hybrid PSO | 97.5% | 98.3% | 98.2% | |

| Singh et al. [26] | 2016 | 63 | Wavelet feature extraction | 100% | 90.9% | 94.7% | |

| Acharya et al. [27] | 2017 | 702 | kNN (K = 2) Glaucoma Risk index | 96.2% | 93.7% | 95.7% | |

| Maheshwari et al. [28] | 2017 | 488 | Variational mode decomposition | 93.6% | 95.9% | 94.7% | |

| Raghavendra et al. [29] | 2017 | 1000 | RT, MCT, GIST | 97.80% | 95.8% | 97% | |

| Ting et al. [7] | 2017 | 494,661 | VGGNet | 96.4% | 87.2% | 0.942 | |

| Kausu et al. [30] | 2018 | 86 | Wavelet feature extraction, Morphological | 98% | 97.1% | 97.7% | |

| Koh et al. [31] | 2018 | 2220 | Pyramid histogram of visual words and Fisher vector | 96.73% | 96.9% | 96.7% | |

| Soltani et al. [32] | 2018 | 104 | Randomized Hough transform | 97.8% | 94.8% | 96.1% | |

| Li et al. [12] | 2018 | 48,116 | Inception-v3 | 95.6% | 92% | 92% | 0.986 |

| Fu et al. [33] | 2018 | 8109 | Disc-aware ensemble network (DENet) | 85% | 84% | 84% | 0.918 |

| Raghavendra et al. [29] | 2018 | 1426 | Eighteen-layer CNN | 98% | 98.30% | 98% | |

| Christopher et al. [34] | 2018 | 14,822 | VGG6, Inception-v3, ResNet50 | 84–92% | 83–93% | 0.91–0.97 | |

| Chai et al. [35] | 2018 | 2000 | MB-NN | 92.33% | 90.9% | 91.5% | |

| Ahn et al. [36] | 2018 | 1542 | Inception-v3 Custom 3-layer CNN |

84.5% 87.9% |

0.93 0.94 |

||

| Shibata et al. [37] | 2018 | 3132 | ResNet-18 | 0.965 | |||

| Mohamed et al. [38] | 2019 | 166 | Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) | 97.6% | 92.3% | 98.6% | |

| Bajwa et al. [39] | 2019 | 780 | R-CNN | 71.2% | 0.874 | ||

| Liu et al. [40] | 2019 | 241,032 | ResNet (local validation) | 96.2% | 97.7% | 0.996 | |

| Al-Aswad et al. [41] | 2019 | 110 | ResNet-50 | 83.7% | 88.2% | 0.926 | |

| Asaoka et al. [42] | 2019 | 3132 | ResNet-34 | 0.965 | |||

| ResNet-34 without augmentation | 0.905 | ||||||

| VGGI I | 0.955 | ||||||

| VGGI 6 | 0.964 | ||||||

| Inception-v3 | 0.957 | ||||||

| Kim et al. [43] | 2019 | 1903 | Inception-V4 | 92% | 98% | 93% | 0.99 |

| Orlando et al. [44] | 2019 | 1200 | Refuge Data Set | 85% | 97.6% | 0.982 | |

| Phene et al. [45] | 2019 | 86,618 | Inception-v3 | 80% | 90.2% | 0.945 | |

| Rogers et al. [46] | 2019 | 94 | ResNet-50 | 80.9% | 86.2% | 83.7% | 0.871 |

| Thompson et al. [47] | 2019 | 9282 | ResNet-34 | 0.945 | |||

| Hemelings et al. [15] | 2020 | 8433 | ResNet-50 | 99% | 93% | 0.996 | |

| Zhao et al. [48] | 2020 | 421 | MFPPNet | 0.90 | |||

| Li et al. [49] | 2020 | 26,585 | ResNet101 | 96% | 93% | 94.1% | 0.992 |

ARCH = Architecture; SEN = Sensibility; SPEC = Specificity; ACC = Accuracy; AUC = Area under the curve.

3. Optical Coherence Tomography

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is an essential tool to capture not only the glaucomatous optic disc in two dimensions (2D) but to provide a three-dimensional (3D) visualization, including the deeper structures. It is a technique based on the optical backscattering of biological structures; it has been widely adopted to assess glaucoma damage both on the anterior segment (e.g., with anterior segment OCT to detect angle closure) and posterior segment (e.g., with traditional OCT to detect ONH morphology and RFNL thickness) [50].

For this reason, depending on the input data, it is possible to differentiate five subgroups of deep learning models: (1) models for prediction of OCT measurements from fundus photography, (2) models based on traditionally segmented OCT acquisitions, (3) models for glaucoma classification based on segmentation-free B-scans, (4) models for glaucoma classification based on segmentation-free 3D volumetric data and (5) models based on anterior segment OCT acquisitions.

Thompson et al. showed that it is possible to predict the Bruch membrane opening-based minimum rim width (BMO-MRW) using optic disc photographs with high accuracy (AUC was 0.945) [51]. Similarly, other researchers reported a high AUC for their model to predict RNFL thickness from fundus images [52,53,54]. Asaoka et al. developed a CNN algorithm to diagnose glaucoma based on thickness segmentations of RNFL and ganglion cells with inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) [42,55]. Wang et al. used 746,400 segmentation-free B-scans from 2669 glaucomatous eyes to automatically develop a model to detect glaucoma with an AUC of 0.979 [56].

Maetschke et al. [57] developed a DL model with an AUC of 0.94 using raw unsegmented 3D volumetric optic disc scans. Similarly, Ran et al. [58] validated a 3D DL model based on 6921 OCT optic disc volumetric scans; the AUC was 0.969, with a comparable performance between the model and glaucoma experts. Russakoff et al. used OCT macular cube scans to train a model to classify referable from non-referable glaucoma; despite the quality of the model, it did not perform as expected on external datasets [59].

At last, DL models based on AS-OCT have been developed to detect the presence of primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG), such as the one proposed by Fu et al. [60]. Xu et al. further developed this type of algorithm to predict the PACG as well as the spectrum of primary angle-closure diseases (PACD) (e.g., primary angle-closure suspect, primary angle-closure) [61].

The papers cited clearly demonstrated that using DL on OCT for glaucoma assessment is effective, precise, and encouraging (Table 2). Despite that, prior to implementing DL on OCT monitoring, more research is required to address some current challenges, including annotation standardization, the AI “black box” explanation problem, and the cost-effective analysis after integrating DL in a real clinical scenario.

Table 2. Summary of studies on glaucoma detection using OCT technology.

| Author | Year | Outcome Measures | Arch | SEN | SPEC | ACC | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OCT Fundus | Thompson et al. [47] | 2019 | 1. Global BMO-MRW prediction | ResNet34 | 0.945 | |||

| 2. Yes glaucoma vs. No glaucoma | ||||||||

| Medeiros et al. [53] | 2019 | 1. RNFL thickness prediction | ResNet34 | 80% | 83.7% | 0.944 | ||

| 2. Glaucoma vs. Suspect/healthy | ||||||||

| Jammal et al. [52] | 2020 | RNFL prediction | ResNet34 | 0.801 | ||||

| Lee et al. [62] | 2021 | RFNL prediction | M2M | |||||

| Medeiros et al. [54] | 2021 | Detection of RFNL thinning from fundus photos | CNN | |||||

| OCT 2D | Asaoka et al. [55] | 2019 | Early POAG vs. no POAG | Novel CNN | 80% | 83.3% | 0.937 | |

| Muhammad et al. [63] | 2017 | Early glaucoma vs. health/suspected eyes | CNN + transfer learning | 93.1% | 0.97 | |||

| Lee et al. [64] | 2020 | GON vs. No GON | CNN (NASNet) | 94.7% | 100% | 0.990 | ||

| Devalla et al. [65] | 2018 | Glaucoma vs. normal | Digital stain of RNFL | 92% | 99% | 94% | ||

| Wang et al. [56] | 2020 | Glaucoma vs. no glaucoma | CNN + transfer learning | 0.979 | ||||

| Thompson et al. [51] | 2020 | POAG vs. no glaucoma | ResNet34 | 95% | 81% | 0.96 | ||

| Pre-perimetric vs. no glaucoma | 95% | 70% | 0.92 | |||||

| Glaucoma with any VF loss (perimetric) vs. no glaucoma | 95% | 80% | 0.97 | |||||

| Mild VF loss vs. no glaucoma | 95% | 85% | 0.92 | |||||

| Moderate VF loss vs. no glaucoma | 95% | 93% | 0.99 | |||||

| Severe VF loss vs. no glaucoma | 95% | 98% | 0.99 | |||||

| Mariottoni et al. [66] | 2020 | Global RNFL thickness value | ResNet34 | |||||

| OCT 3D | Ran et al. [58] | 2019 | Yes GON vs. No GON | CNN (NASNet) | 89% | 96% | 91% | 0.969 |

| 78–90% | 86% | 86% | 0.893 | |||||

| Maetschke et al. [57] | 2019 | POAG vs. no POAG | Feature-agnostic CNN | 0.94 | ||||

| 0.92 | ||||||||

| Russakoff et al. [59] | 2020 | Referable glaucoma vs. non-referable glaucoma | gNet3D-CNN | 0.88 | ||||

| AS-OCT | Fu et al. [60] | 2019 | Open angle vs. Angle closure | VGG-16 + transfer learning | 90% | 92% | 0.96 | |

| Fu et al. [67] | 2019 | Open angle vs. Angle closure | CNN | 0.9619 | ||||

| Xu et al. [61] | 2019 | 1. Open angle vs. angle closure | CNN (ResNet18) + transfer learning | 0.928 | ||||

| 2. Yes/PACD vs. no PACD | 0.964 | |||||||

| Hao et al. [68] | 2019 | Open angle vs. Narrowed Angle vs. Angle closure | MSRCNN | 0.914 |

ARCH = Architecture; SEN = Sensibility; SPEC = Specificity; ACC = Accuracy; AUC = Area under the curve.

SEN = Sensibility, SPEC = Specificity, ACC = Accuracy, AUC = Area under the curve.

4. Standard Automatic Perimetry

Visual field testing represents a fundamental exam for diagnosing and monitoring glaucoma. In distinction from the fundus photographs and OCT, it allows the interpretation of the functionality of the whole visual pathway. Given the importance of visual function testing for the detection and clinical forecast of glaucoma, many researchers recently developed DL algorithms using the complex quantitative data it contains. Asaoka et al. [69] trained a DL algorithm to automatically detect glaucomatous visual field loss with an AUC of 0.926; the performance of their model was higher if compared to other machine learning classifiers methods, such as random forests (AUC 0.790) and support vector machines (AUC 0.712).

Elze et al. [70] employed archetypal analysis technology to obtain a quantitative measurement of the impact of the archetypes or prototypical patterns constituting visual field alterations. Similarly, Wang et al. developed an artificial intelligence approach to detect visual field progression based on spatial pattern analysis [71].

Given the importance of predicting visual loss patterns in glaucoma patients, specifically for prescribing a personalized treatment, researchers have developed interesting tools to predict the probability of disease progression based on visual field data. DeRoos et al. [72] were able to compare forecasted changes in mean deviation (MD) on perimetry at different target pressures using a machine-learning technique called Kalman Filtering (KF). KF is a machine-learning technique derived from the aero-spatial industry that compares the course of the disease of a single patient to a population of patients with the same chronic disease; in this scenario, it could potentially predict the rate of conversion to glaucoma in patients with ocular hypertension as well as disease progression in the future for patients with manifest glaucoma (Table 3). [73,74].

Table 3. Summary of studies on artificial intelligence applied to visual field testing.

| Author | Year | Outcomes Mesures | Architecture | SEN | SPEC | ACC | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asaoka et al. [69] | 2016 | Pre-perimetric VFs vs. VFs in healthy eyes | FNN | 0.926 | |||

| Kucur et al. [75] | 2018 | Early glaucomatous VF loss vs. no glaucoma | CNN with Voronoi representation | ||||

| Li et al. [12] | 2018 | Glaucomatous VF loss vs. no glaucoma | VGG I 5 | 93% | 83% | 88% | 0.966 |

| Li et al. [76] | 2018 | Glaucoma vs. Healthy | VGG | 93% | 3% | 0.966 | |

| Berchuck et al. [77] | 2019 | Rates of VF progression compared to SAP MD; Prediction of future VF compared to point-wise regression predictions | Deep variational autoencoder | ||||

| Wen et al. [78] | 2019 | HFA points and Mean Deviation | CascadeNet-5 | ||||

| Kazemian et al. [74] | 2018 | Forecasting visual field progression | Kalman Filtering Forecasting | ||||

| Garcia et al. [73] | 2019 | Forecasting visual field progression | Kalman Filtering Forecasting | ||||

| DeRoos et al. [72] | 2021 | Forecasting visual field progression | Kalman Filtering Forecasting |

The possibility of low-cost screening tests for the disease has been made possible by the consistent demonstration of deep learning models’ ability to detect and quantify glaucomatous damage using standard automated perimetry automatic assessment. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that DL enhances the evaluation of the damage on unprocessed visual field data, which could enhance the utility of these tests in clinical practice. As already stated, the validation of new diagnostic tests, despite how exciting AI technologies may be, should be based on a rigorous methodology, with special attention to the way the reference standards are classified and the clinical settings in which the tests will be adopted.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms24032814

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!