2. Applications of “Unprotected” Metal Nanoclusters

2.1. Application in Catalysis

2.1.1. Exploring the Structure–Function Relationship of Metal Nanocluster Catalysts

It is well known that the composition, size and surface structure of metal nanoclusters, as well as the environment surrounding the metal nanoclusters, have significant influences on the electronic and geometric structures of the metal nanoclusters, which determine the catalytic activity, selectivity and stability of the metal nanocluster-based catalysts [

108,

109,

110,

111]. Unprotected metal nanoclusters provide tractable tools for experimentally studying the effects of individual factors such as the metal composition, size, support, and the surface modification groups on the catalytic properties of metal nanocluster catalysts by assembling structure-controllable catalysts with unprotected metal or alloy nanoclusters that act as the building blocks [

21,

45,

112,

113,

114,

115]. A theoretical calculation based on the experimental results could further deepen the understanding of the relationship between the structure and performance of the catalytic sites of metal nanocluster catalysts [

55,

116]. Based on the relevant experimental and theoretical research results described in this section, in this paper, we propose a principle of the influence of carriers, ligands and modifiers in metal nanocluster catalysts on the catalytic properties. The main points of the principle are as follows:

Chemical bonding or electron transfer between carriers, ligands or modifiers and metal nanoclusters can alter the distribution of electrons (or charge) and the metal atom spacing of the metal nanoclusters in the catalysts. The changes have the following characteristics:

- (1)

-

They change the extent of charge separation between the surface atomic layer and core of the metal nanocluster. The electron donation from the support or ligand will increase the charge separation extent, leaving the surface atomic layer with a more negative charge.

- (2)

-

They change the charge distribution state of the metal nanocluster surface atomic layer at the atomic (or subatomic) scale and make it more uneven compared with that of the naked metal nanocluster.

- (3)

-

They change the distance between some of the metal atoms.

- (4)

-

The extent of the change in the charge distribution or atomic spacing is related to the size of the metal nanocluster. Usually, small-sized metal nanoclusters exhibit more significant changes.

- (5)

-

Catalytic sites composed of surface metal atoms with different charge states or atomic spacings exhibit different adsorption energies for a reactant and reaction energy barrier, showing different catalytic activities and product selectivities. The species in the support surface (the ion, vacancy or chemical group) or the ligand adjacent to the metal nanocluster can form complex (or synergistic) catalytic sites with metal nanocluster surface atoms, at which the adsorption energies of the reactants and chemical reaction energy barriers are influenced by coordination polarization or hydrogen bonding, resulting in a synergistic catalytic effect.

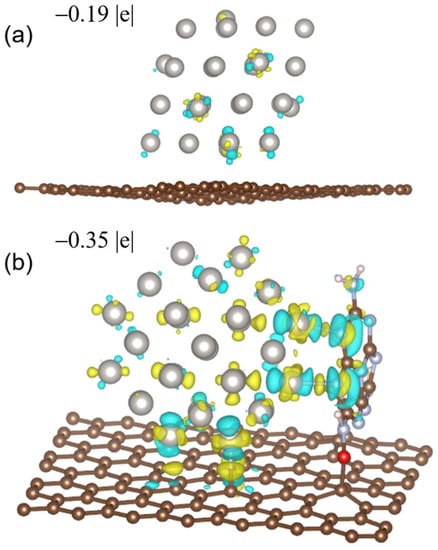

In a recent research [

116], we synthesized two catalysts (Pt/MMC-6.8N and Pt/VXC-72R) with the same sized Pt nanoclusters and different supports by assembling the unprotected Pt nanoclusters with a mean diameter of 1.4 nm with a melem-modified carbon carrier containing 6.8 wt% of N (MMC-6.8 N) and a carbon carrier VXC-72R. These catalysts were used to catalyzed the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), a crucial reaction in fuel cells. It was found that the mass activity (MA) of Pt/MMC-6.8N at 0.9 V (vs. RHE) reached 907 mA mg

−1Pt (this is 2.1 times larger than the U.S. Department of Energy’s target for 2020 (440 mA mg

−1Pt)), which was 3.9 and 4.2 times larger those of Pt/VXC-72R and a commercial Pt/C catalyst of similar Pt particle sizes, respectively. After ten thousand voltage cycles from 1.0 to 1.5 V at 60 °C, the MA of Pt/MMC-6.8N decreased by 2%, while the MA loss of Pt/VXC-72R was 40%. The remarkable promotion effects of MMC on the catalytic activity and durability were intensively studied using a series of characterization technologies and a density functional theory (DFT) calculation. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and XANES are commonly used to investigate the relationship between the catalytic performance and electron binding energy or electron occupation status of metal nanocluster catalysts. To our surprise, we could not find any obvious difference in the apparent valence states of the Pt nanoclusters between the two catalysts in the XPS and XANES analyses. However, the DFT calculation based on the model catalysts for the two prepared catalysts demonstrated obvious differences in the charge distribution on the metal nanocluster surfaces and across the entire metal nanoclusters. The model catalysts for Pt/VXC-72R and Pt/MMC-6.8N (Pt

40/C and Pt

40/MMC) are composed of Pt NCs with 40 Pt atoms (Pt

40 NCs, about 1 nm in diameter) and a graphene sheet and a melem-modified graphene sheet, respectively. It was found that the Pt

40 NC in Pt

40/MMC is chemically bounded to two nitrogen atoms of the melem group and one C atom of the melem-modified graphene sheet, while the Pt

40 NC in Pt

40/C does not form any chemical bond with the graphene sheet. The charge density differences and Bader charges of Pt

40 NCs in Pt

40/C and Pt

40/MMC have been calculated, and they are shown in

Figure 1. It was found that the Bader charges of Pt

40 NCs in Pt

40/MMC (−0.35 |e|) are close to those in Pt

40/C (−0.19 |e|), which is consistent with the XANES and XPS characterization results, reflecting the average electronic states of the Pt NCs in the catalysts. However, the negative charge of the outer layer Pt atoms in Pt

40 NC of Pt

40/MMC is much larger than that of Pt

40/C, and the charging extents of different surface atoms of Pt

40 NCs in Pt

40/MMC are quite different, which are derived from the interaction between MMC and Pt

40 NC (

Figure 2).

Figure 1. The charge density difference (isosurface unit = 4 × 10

−3 e per Bohr

3) and Bader charges of Pt

40 NCs of (

a) Pt

40/C and (

b) Pt

40/MMC. The yellow and blue surface represent the charge increase and decrease, respectively. The Bader charges of the Pt atoms at the marked adsorption sites for OOH* and OH

−* on Pt/C with an average value of −0.049 |e| are less than that on Pt/MMC (with an average value of −0.077 |e|). Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2022 Wiley-VCH GmbH [

116].

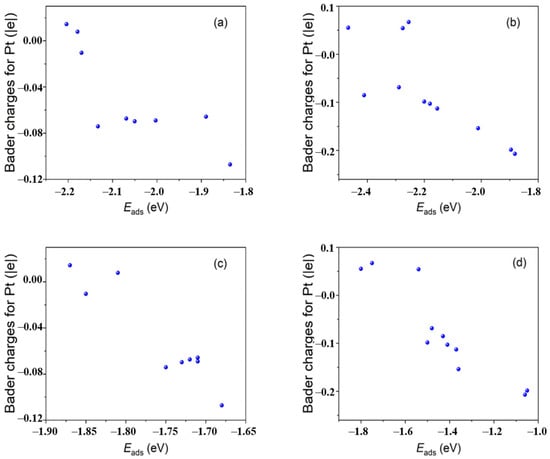

Figure 2. Plots of Bader charges of the representative adsorption site Pt atoms versus adsorption energies of OOH* on Pt

40 NCs of Pt

40/C (

a) and Pt

40/MMC (

b); plots of Bader charges of the representative adsorption site Pt atoms versus adsorption energies of OH

−* on Pt

40 NCs of Pt

40/C (

c) and Pt

40/MMC (

d). Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2022 Wiley-VCH GmbH [

116].

The high negative charge of the catalytic site weakens the adsorption of OH−*. On the other hand, the formation of a hydrogen bond between the intermediate OOH* and N atoms in MMC on some catalytic sites of Pt40/MMC increases the adsorption energy of OOH*. The obviously enhanced catalytic activity for ORR of Pt/MMC compared that of Pt/C is attributed to the decrease in OH−* adsorption energy and the increase in OOH* adsorption energy at some sites of Pt/MMC. The chemical bonds between the Pt nanoclusters and the MMC carriers explain the high durability of Pt/MMC.

In 2004, we were the first to present that compared with the catalytic sites of the metal nanocluster themselves, the catalytic sites composed of metal nanocluster surface atoms and the adjacent surface oxygen vacancy of the metal oxide supports may exhibit much better catalytic properties [

11], indicating a synergistic effect between the metal nanoclusters and adjacent surface oxygen vacancies. For a Ru/SnO

2 catalyst assembled with unprotected Ru nanoclusters and tin oxide colloidal nanoparticles, with an average Ru particle size of 1.3 nm, the average catalytic activity (4.3 × 10

−2 mol

o-CNB mol

−1Ru s

−1) for the selective hydrogenation of ortho-chloronitrobenzene (

o-CNB) to ortho-chloroaniline (

o-CAN) was much higher than that of the PVP-protected Ru nanoclusters prepared with the same unprotected Ru nanoclusters (6.9 × 10

−3 mol

o-CNB mol

−1Ru s

−1). It was proposed that the oxygen vacancies or coordination-unsaturated Sn

4+ or Sn

2+ species at the support surface surrounding the Ru metal nanoclusters may activate the polar NO

2 groups of

o-CNB and coordinate with the NH

2 groups of the produced

o-CAN molecules, thereby significantly promoting the hydrogenation of

o-CNB and depressing the dehalogenation of

o-CAN. The selectivity for

o-CAN of Ru/SnO

2 reached 99.9%, which is much higher than that of the Ru/SiO

2 prepared with the same unprotected Ru nanoclusters (95%) after complete

o-CNB conversion, which is due to the hydrodechlorination rate being much lower for Ru/SnO

2. Soon after, this concept was successfully applied to develop highly efficient catalysts for the selective hydrogenation of halonitrobenzenes to corresponding haloanilines by depositing unprotected Pt metal nanoclusters onto iron oxide supports [

12,

16,

19]. It was found that during the activation of the catalysts, Pt nanoclusters could catalyze the partial reduction of iron oxide, thus forming oxygen vacancies surrounding the Pt nanoclusters. The partially reduced iron-oxide supported Pt nanocluster catalyst showed much high catalytic activity and selectivity for

o-CAN than the Pt/C catalyst with the same size of Pt nanoclusters did, and the catalytic dehalogenation side reaction of was completely suppressed at 100% conversion of the substrates over the Pt/iron oxide catalysts. The interaction between the Pt nanoclusters and the surface oxygen vacancies resulted in an increase in the electron binding energy of Pt 4f

7/2 in the partially reduced Pt/γ-Fe

2O

3 (Pt/γ-Fe

2O

3-PR), which is 0.5 eV higher than that of the same sized Pt nanoclusters protected by PVP, as measured using an in situ XPS spectrometer, indicating the electron transfer from Pt nanoclusters to iron cations in the catalyst [

16]. The high selectivity for haloanilines in the hydrogenation of halonitrobenzenes was attributed to the electron-deficient state of the Pt nanoclusters supported on the partially reduced iron oxide supports, which may have weakened the extent of electron feedback from the Pt particles to the aromatic ring in

o-CAN and suppressed the hydrodechlorination of the haloanilines.

Pt/γ-Fe

2O

3, Pt/α-Fe

2O

3, Ir/γ-Fe

2O

3, Rh/γ-Fe

2O

3 and Ru/γ-Fe

2O

3 were prepared by depositing the corresponding unprotected platinum group metal (PGM) NCs onto the iron oxide supports and treating the solid products with H

2 at 373 K. A universal rule was revealed for the first time through IR-CO probe and CO chemisorption measurements on these samples, namely, the PGM NCs supported on partially reduced iron oxides have an extremely weak affinity for CO [

16,

19]. This should be derived from the electron transfer from PGMs NCs to the surface oxygen vacancies of the iron oxides and weaken the degree of electron back-donation from the nanocluster surface atoms to CO. This discovery is very helpful for understanding the unique catalytic properties of these catalysts in many reactions.

We succeeded in the preparation of unprotected PtCu alloy nanoclusters with solid solution structures and controllable Pt-to-Cu ratio (1:3-9:1) using a modified alkaline glycol method by introducing acetate ions into the reaction system [

21,

118]. MMC-supported alloy nanocluster catalysts (PtCu/MMC) with an average diameter of ca. 2 nm and different Pt/Cu ratios were prepared by assembling the PtCu alloy nanoclusters and MMC, which were used as catalysts for ORR. The alloy catalyst with a Pt/Cu ratio of 3:1 showed not only the highest MA (1.59A mg

−1Pt @0.9 V), but it also showed the highest specific activity (SA) (3.98 mA cm

−2Pt @0.9 V) among the tested catalysts. As the particle sizes of the alloy nanoclusters in the catalysts are almost the same, the effect of the Pt/Cu ratio on the activity should be mainly derived from the electronic properties of the nanoclusters. As revealed by the in situ XPS measurements, the electron transfer from Cu to Pt occurred in the alloy nanoclusters, which may be the reason why PtCu alloy catalysts exhibit enhanced catalytic activity for ORR compared to that of Pt/MMC. From a further comparison of the catalytic activation of Pt

3Cu

1/MMC, Pt

3Cu

1/C and Pt/C, it was found that the alloying effect increased the MA by 1.4 times, while the promoting effect of MMC increased the MA by 3.2 times.

We prepared a PtRu/NCNHs composite using N-doped carbon nanohorns (NCNHs) and unprotected PtRu NCs with an average PtRu particle size of 1.9 nm, which was used as a catalyst for the electrochemical oxidation of methanol [

20]. The MA of PtRu/NCNHs (850 mA mg

−1PtRu @0.9 V) was 2.5 and 1.7 times larger than those of a commercial PtRu/C catalyst and a homemade PtRu/Vulcan carbon catalyst, respectively. The SA of PtRu/NCNHs (1.35 mA cm

−2PtRu @0.9 V) was 1.8 times larger than that of PtRu/Vulcan carbon. The TEM, ICP and XPS results showed that the three catalysts had similar PtRu particle sizes and Pt/Ru atomic ratios. The Pt 4f and Ru 3p electron binding energies of PtRu/NCNHs had a negative shift of 0.2 eV compared with the corresponding values of PtRu/Vulcan, which was attributed to metal–support interactions, indicating the electron transfer from NCNHs to PtRu NCs in the PtRu/NCNHs catalyst. Based on the proposed principle described above, the improved catalytic activity for the oxidation of CH

3OH and carbonaceous intermediates of PtRu/NCNHs compared to that of PtRu/Vulcan carbon might be derived from the unique structure of complex catalytic sites in the catalyst.

In order to reveal the ligand effects, we investigated the effect of the organic ligands on the Pt 4f electron binding energies of small Pt nanoclusters [

27]. The same sized Pt nanoclusters (d

av = 1.3 nm, size distribution of between 0.8 and 2.8 nm) modified with C

12H

25NH

2, C

12H

25SH, PPh

3, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) were prepared by the surface modification of the unprotected Pt nanoclusters. The 4f

7/2 level electron binding energies of Pt in the prepared C

12H

25NH

2-, PVP-, PVA-, PPh

3- and C

12H

25SH-protected Pt nanoclusters increased by 0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.6 and 0.8 eV than that of bulk Pt, respectively, as measured by XPS. Since the weak interaction between the PVA and Pt nanoclusters cannot affect the core-level electron binding energy of the Pt core to an observable extent, the increment in the Pt 4f binding energy of the PVA-protected Pt nanocluster was mainly derived from the metal particle size effect, originating from the final state relaxation [

27]. The surface modification of the Pt nanoclusters with C

12H

25SH caused a further increase in the Pt 4f

7/2 electron binding energies of 0.3 eV, which is mainly caused by the formation of the Pt–S bond and the coordination of mercaptan groups on the surface Pt atoms. Although the measured Pt 4f electron binding energies of the Pt nanoclusters protected by C

12H

25NH

2, PVP, PVA or PPh

3 are very similar to each other, the charge distribution of these metal nanoclusters should be quite different since the intensities of electronic interaction between these ligands and Pt nanoclusters are different. Recently, the catalytic activities of these protected Pt nanoclusters for the hydrogenation of para-chloronitrobenzene (

p-CNB) were measured [

45]. The initial catalytic activities of the C

12H

25SH-, PPh

3-, C

18H

37NH

2- or PVP-modified Pt nanoclusters with the same sized Pt nanoclusters were 4.7, 4.1, 3.1 and 1.6 mol

hydrogen (mol

Pt S)

−1, respectively, and the selectivity for the byproduct aniline at a

p-CNB conversion of about 40% followed the trend: Pt–PPh

3 > Pt–C

18H

37NH

2 > Pt–PVP > Pt–C

12H

25SH. We believe that the activity and selectivity of these protected Pt NCs are related to the different charge distribution of the metal NCs.

The size effects of Pt nanoclusters in Pt/Fe

2O

3 catalysts for the CO oxidation at room-temperature were investigated by Zhang et al. [

131]. The Pt/Fe

2O

3-a, Pt/Fe

2O

3-b and Pt/Fe

2O

3-c catalysts were prepared by depositing unprotected Pt nanoclusters with mean diameters of 1.1, 1.9 and 2.7 nm on the surface of Fe(OH)

3 powders, respectively, followed by high-temperature calcination in a flow of 20% O

2/Ar. Unprotected Pt nanoclusters colloids with different average particle sizes were prepared by changing the metal concentration or water content in the alkaline EG method [

10,

131]. The catalytic tests on the oxidation of CO to CO

2 at a low temperature showed that the Pt/Fe

2O

3-b catalyst exhibited the highest activity among the tested catalysts, with a 42% conversion of CO at room temperature and a complete conversion of CO at around 60 ℃. For Pt/Fe

2O

3-a and Pt/Fe

2O

3-c, the CO conversion rates were 20% and 8% at room temperature, while the complete conversion of CO was realized at 70 and 90 ℃, respectively. The XPS and XANES measurement results indicate that the Pt nanocluster size affected the Pt species chemical states in the Pt/Fe

2O

3 catalysts. The Pt atoms in Pt/Fe

2O

3-a had been largely oxidized to Pt

2+, while the majority of the Pt atoms in Pt/Fe

2O

3-b and Pt/Fe

2O

3-c were in the Pt

0 oxidation state, with Pt/Fe

2O

3-c containing the most Pt atoms in a metallic state.

2.1.2. Application in Fabrication of Smart Catalysts

The unprotected metal nanoclusters prepared based on the alkaline EG method have been widely applied in the fabrication of metal nanocluster-based catalysts with excellent catalytic properties [

53,

54,

55,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141].

Size- or shape-selective catalysts have important applications for the production of fine chemicals. Li and Yang et al. reported the first example of the encapsulation of unprotected Pt nanoclusters in zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) to prepare heterogeneous catalysts with high size selectivity for the substrates in the catalytic hydrogenation of alkenes [

50]. In this preparation, 2-Methyl imidazole plays both the roles of the Pt NPs stabilizer and the conjunction linker of ZIF-8. The catalytic performance of the Pt@ZIF-8 catalysts prepared by this hetero-nucleation strategy was much better than that of the ZIF-8 encapsulated with PVP-protected Pt NPs. It would be expected that other polydentate ligands that are capable of capping the unprotected metal NPs could also be employed to fabricate various metal NPs@MOFs with the same strategy, providing an effective way to design and synthesize size- or shape-selective catalysts. Moreover, Li and Yang et al. reported an efficient approach for the encapsulation of the unprotected Pt nanoclusters into nanocages of cage-like mesoporous silicas (CMS) [

142]. The prepared Pt/CMS catalysts exhibited high selectivity (>99%) for the corresponding CAN in the hydrogenation of CNB.

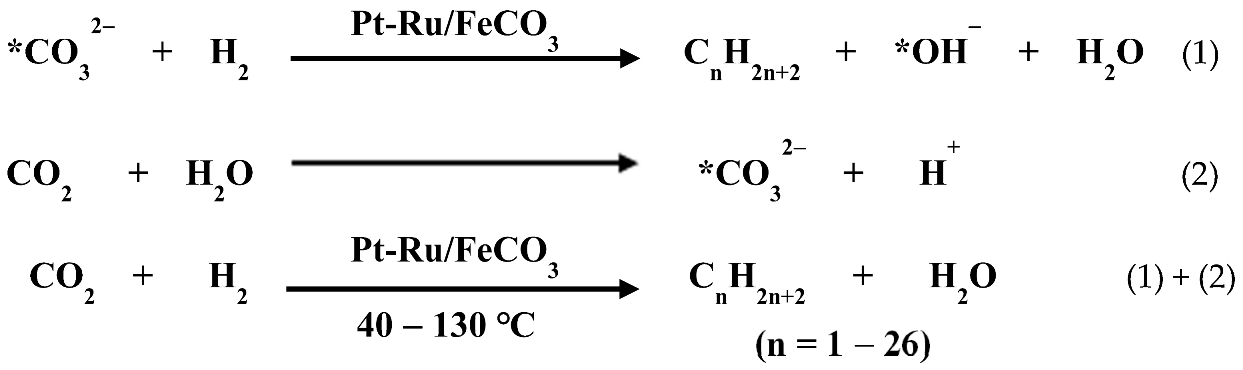

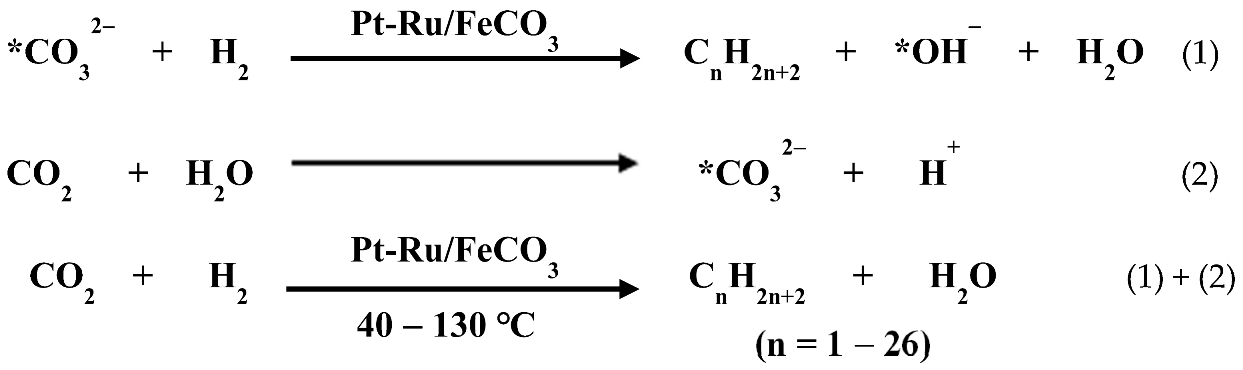

The catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide to produce multi-carbon compounds is of significance because it will make carbon dioxide an important carbon resource for the synthesis of sustainable energy sources or fine chemicals, thereby reducing the dependence on fossil fuels [

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151]. For most reported catalysts, the synthesis of multi-carbon compounds through CO

2 hydrogenation usually needs to be carried out at high temperatures of 200–350 °C. The development of new catalytic systems to generate liquid fuels or highly valued fine chemicals by consuming CO

2 under mild conditions would bring about many economic and environmental benefits. Recently, we reported a new method for the catalytic conversion of CO

2 to multi-carbon compounds at low temperatures [

53,

152]. At 40–130 °C, in a catalyst of ferrous carbonate-supported Pt nanoclusters and Ru nanoclusters, the Pt and Ru nanoclusters can catalyze the hydrogenation of the carbonate ions to form high hydrocarbons and multi-carbon alcohols. The carbon atom number in the high hydrocarbons could be as high as 26. Coupling this process with the carbonation of the resulting metal species enables the catalytic conversion of CO

2 to high hydrocarbons and multi-carbon alcohols [

53]. The reaction equations are shown as follows:

At 40 °C, the selectivities for C

5–C

26 hydrocarbons and C

2+ compounds reached 49.6% and 77.7%, respectively, while at 130 °C, the selectivities for them were 26.1% and 45.8%, respectively, while for the conversion of carbon in the substrates (including FeCO

3 and CO

2) over 8 h, it was 5.1%. CO was not detected by gas chromatography (GC) in the products. The experimental results indicated that the simultaneous presence of platinum and ruthenium in the catalyst is beneficial to improve the selectivity of multi-carbon compounds. This encouraged us to improve the selectivity of multi-carbon compounds in the products by regulating the distribution of Pt and Ru elements in the catalyst. Pt nanocrystals anchoring small Ru clusters on carbon (Ru-

co-Pt/C) [

55] were prepared using unprotected Pt and Ru nanoclusters as starting materials through the Pt nanocluster catalyzing atomization of Ru nanoclusters and a surface growth process at 130 °C in a mixture of water and cyclohexane in a gaseous mixture of CO

2 and H

2 and characterized by HRTEM, EDX, EXAFS and XPS. Carbon-supported Pt or Ru nanoclusters were prepared by the immobilization of the Pt or Ru nanoclusters on a carbon support, and these were used as catalysts for comparison. At 130 °C, in a mixture of water and cyclohexane, the Ru/C catalyst exhibited a high activity for CO

2 hydrogenation with a selectivity for methane of 94.3%, while the catalytic activity of the Pt/C catalyst was quite low under this condition. Ru-

co-Pt/C could catalyze CO

2 hydrogenation to produce hydrocarbons and alcohols with a selectivity of 90.1% for the C

2+ compounds, far exceeding the previously reported values, which suggests that CO

2 hydrogenation of Ru-

co-Pt/C tends to produce multi-carbon compounds. The yield of organic hydrogenation products after 22 h of reaction reached 8.9% of Ru-

co-Pt/C under this condition. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to study the origin of the significant increase in multi-carbon product selectivity in the CO

2 hydrogenation products of the bimetallic catalyst compared to those of the Ru/C and Pt/C catalysts. The established model clusters used to simulate the three catalysts contain 50 metal atoms (

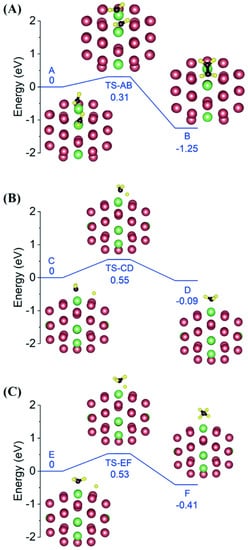

Figure 3), and the bimetallic cluster has 3 Ru dimers and 2 individual Ru atoms anchored on the NC surface.

Figure 3. The optimized geometries of reactants, transition states and products for (

A) CH

2 + CH

2 coupling, (

B) CH

2 hydrogenation and (

C) CH

3 hydrogenation on a Pt

42-Ru

8 bimetallic cluster, respectively. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2022 The Royal Society of Chemistry [

55].