In the U.S., racial disparities are present among children, with Hispanic and Black children carrying the burden of infectious respiratory disease occurrence. Several factors are contributory to these outcomes among Hispanic and Black children, including higher rates of poverty; higher rates of chronic conditions, such as asthma and obesity; and seeking care outside of the home. However, vaccinations can be used to reduce the risk of infection among Black and Hispanic children. Whether a child is very young or a teen, racial disparities are present in occurrence rates of infectious respiratory diseases, with the burden resting among minorities. Therefore, it is important for parents to be aware of the risk of infectious diseases and to be aware of resources, such as vaccines.

- infectious diseases

- communicable diseases

- contagious diseases

1. Introduction

2. Systematic Review

Racial Disparities

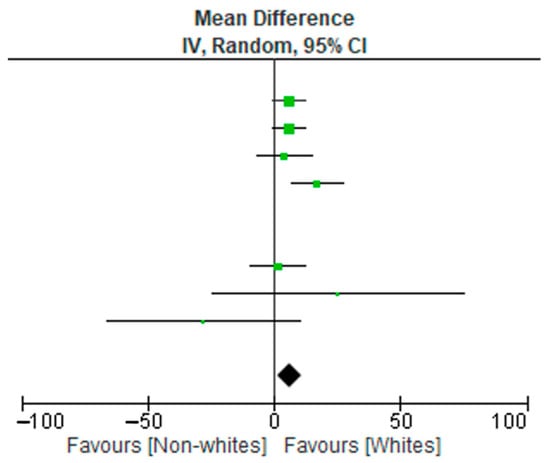

3. Meta-Analysis

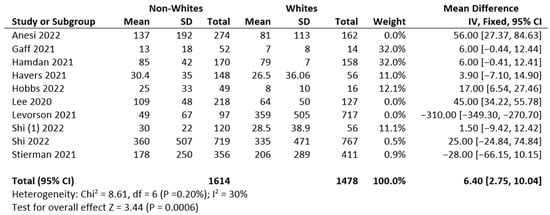

4. Risk of Bias

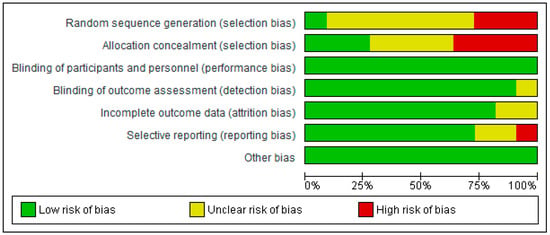

5. Risk of Bias Summary

| Authors/Studies | Comments |

|---|---|

| Anesi et al. 2022 [14] | Self-reported data for a few participants were included in this analysis, a few infants may have been misclassified due to maternal vaccination status, or the mothers’ recollection of complete COVID-19 vaccination may be imperfect, as reported by the author as limitations. The small sample sizes mentioned by the authors resulted in wide confidence intervals. |

| Levorson et al. 2021 [16] | The regional population representativeness may have been affected by selection bias because the methodology focused on self-referral, and subjects in the study had blood labs completed for other clinical purposes. The authors made adjustments for these factors. |

| Shi et al. 2022 [13] | As mentioned by the authors, COVID-19 hospitalizations may have been overlooked because of testing practices and availability. Detailed clinical data are limited for the period during which the omicron variant was predominant (19–31 December 2021). The data do not include the peak of hospitalizations during this period; the delta variant was prevalent in late December. |

| Perez et al. 2022 [11] | New Vaccine Surveillance Network data are limited to enrolled consenting participants, who may not be representative of all children receiving health care, as mentioned by the authors as limitations. |

| Stierman et al. 2021 [19] | The proportion of positive SARS-CoV-2 test results recorded in drive-through clinics increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as reported in the paper. This study focused on counties with complete ethnicity and race data. The results may not be generalizable to larger populations, as suggested by the authors. |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diseases11010023

References

- Shapiro, N. Tripledemic Update: RSV, Covid and Flu. Forbes 13 December 2022. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ninashapiro/article/whats-a-tripledemic-rsv-covid-and-flu/?sh=226354f77579 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Miguel, C.P.V.; Dasgupta-Tsinikas, S.; Lamb, G.S.; Olarte, L.; Santos, R.P. Race, Ethnicity, and Health Disparities in US Children With COVID-19: A Review of the Evidence and Recommendations for the Future. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2022, 11, S132–S140.

- PIDS. What’s in the News. What’s in the News—Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Available online: https://pids.org/2021/05/07/whats-in-the-news-socioeconomic-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-mis-c/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Thinking About Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Impacts. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 27 April 2020. Available online: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/thinking-about-racial-disparities-in-covid-19-impacts-through-a-science-informed-early-childhood-lens/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Smitherman, L.C.; Golden, W.C.; Walton, J.R. Health Disparities and Their Effects on Children and Their Caregivers During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 68, 1133–1145.

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Blau, D.M.; Caballero, M.T.; Feikin, D.R.; Gill, C.J.; A Madhi, S.; Omer, S.B.; Simões, E.A.F.; Campbell, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 2047–2064.

- Okomo, U.; Idoko, O.T.; Kampmann, B. The burden of viral respiratory infections in young children in low-resource settings. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e454–e455.

- Schot, M.J.C.; Dekker, A.R.J.; Van Werkhoven, C.H.; Van Der Velden, A.W.; Cals, J.W.L.; Broekhuizen, B.D.L.; Hopstaken, R.M.; De Wit, N.J.; Verheij, T.J.M. Burden of disease in children with respiratory tract infections in primary care: Diary-based cohort study. Fam. Pract. 2019, 36, 723–729.

- Goto, T.; Tsugawa, Y.; Mansbach, J.M.; Camargo, C.A.; Hasegawa, K. Trends in Infectious Disease Hospitalizations in US Children, 2000 to 2012. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, e158–e163.

- Severe Respiratory Illness Increasing in Children: What You Need to Know. RWJBarnabas Health. Available online: https://www.rwjbh.org/blog/2022/november/severe-respiratory-illness-increasing-in-childre/ (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Perez, A.; Lively, J.Y.; Curns, A.; Weinberg, G.A.; Halasa, N.B.; Staat, M.A.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Stewart, L.S.; McNeal, M.M.; Clopper, B.; et al. Respiratory Virus Surveillance Among Children with Acute Respiratory Illnesses—New Vaccine Surveillance Network, United States, 2016–2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1253–1259.

- Marks, K.J.; Whitaker, M.; Agathis, N.T.; Anglin, O.; Milucky, J.; Patel, K.; Pham, H.; Kirley, P.D.; Kawasaki, B.; Meek, J.; et al. Hospitalization of Infants and Children Aged 0–4 Years with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 2020–February 2022. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 429–436.

- Shi, D.S.; Whitaker, M.; Marks, K.J.; Anglin, O.; Milucky, J.; Patel, K.; Pham, H.; Chai, S.J.; Kawasaki, B.; Meek, J.; et al. Hospitalizations of Children Aged 5–11 Years with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 2020–February 2022. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 574–581.

- Anesi, J. Commentary: Effectiveness of two-dose vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19-associated hospitalizations among immunocompromised adults—Nine states, January–September 2021. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 22, 304–305.

- Shi, D.S.; Hause, A.M.; Gee, J.; Baggs, J.; Abara, W.E.; Marquez, P.; Thompson, D.; Su, J.R.; Licata, C.; Rosenblum, H.G.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Safety in adolescents aged 12–17 years—United States, December 14, 2020–July 16, 2021. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 1053–1058.

- Levorson, R.E.; Christian, E.; Hunter, B.; Sayal, J.; Sun, J.; Bruce, S.A.; Garofalo, S.; Southerland, M.; Ho, S.; Levy, S.; et al. A cross-sectional investigation of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and associated risk factors in children and adolescents in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259823.

- Lee, E.H.; Kepler, K.L.; Geevarughese, A.; Paneth-Pollak, R.; Dorsinville, M.S.; Ngai, S.; Reilly, K.H. Race/Ethnicity Among Children With COVID-19–Associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2030280.

- Kurup, S.; Burgess, R.; Tine, F.; Chahroudi, A.; Lee, D.L. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Racial Disparities in Children: Protective Mechanisms and Severe Complications Related to MIS-C. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2022, 9, 1536–1542.

- Stierman, B.M.; Abrams, J.Y.P.; Godfred-Cato, S.E.D.; Oster, M.E.M.; Meng, L.; Yip, L.; Patel, P.M.; Balachandran, N.M.; Prezzato, E.M.; Pierce, T.M.; et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children in the United States, March 2020 to February 2021. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e400–e406.

- Zambrano, L.D.; Ly, K.N.; Link-Gelles, R.; Newhams, M.M.; Akande, M.; Wu, M.J.; Feldstein, L.R.; Tarquinio, K.M.; Sahni, L.C.; Riggs, B.J.; et al. Investigating Health Disparities Associated With Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children After SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, 891–898.

- Hobbs, C.V.; Kim, S.S.; Vemula, P.; Inagaki, K.; Harrison, V.A.; Malloch, L.; Martin, L.M.; Singh, G.; Agana, U.; Williams, J.M.; et al. Active Surveillance With Seroprevalence-based Infection Rates Indicates Racial Disparities With Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 Requiring Hospitalization in Mississippi, March 2020–February 2021. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, 736–741.

- Mody, A.; Pfeifauf, K.; Bradley, C.; Fox, B.; Hlatshwayo, M.G.; Ross, W.; Sanders-Thompson, V.; Maddox, K.J.; Reidhead, M.; Schootman, M.; et al. Understanding Drivers of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Racial Disparities: A Population-Level Analysis of COVID-19 Testing Among Black and White Populations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, e2921–e2931.

- Graff, K.; Smith, C.; Silveira, L.; Jung, S.; Curran-Hays, S.M.; Jarjour, J.; Carpenter, L.B.; Pickard, K.B.; Mattiucci, M.; Fresia, J.B.; et al. Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e137–e145.

- Mannheim, J.; Konda, S.; Logan, L.K. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 infection amongst children. Paediatr. Périnat. Epidemiol. 2022, 36, 337–346.

- Brandt, K.; Goel, V.; Keeler, C.; Bell, G.J.; Aiello, A.E.; Corbie-Smith, G.; Wilson, E.; Fleischauer, A.; Emch, M.; Boyce, R.M. SARS-CoV-2 testing in North Carolina: Racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities. Health Place 2021, 69, 102576.

- Gualandi, N.; Mu, Y.; Bamberg, W.M.; Dumyati, G.; Harrison, L.H.; Lesher, L.; Nadle, J.; Petit, S.; Ray, S.M.; Schaffner, W.; et al. Racial Disparities in Invasive Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections, 2005–2014. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 1175–1181.

- Hansen, C.; Perofsky, A.C.; Burstein, R.; Famulare, M.; Boyle, S.; Prentice, R.; Marshall, C.; McCormick, B.J.J.; Reinhart, D.; Capodanno, B.; et al. Trends in Risk Factors and Symptoms Associated With SARS-CoV-2 and Rhinovirus Test Positivity in King County, Washington, June 2020 to July 2022. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2245861.

- O’Halloran, A.C.; Holstein, R.; Cummings, C.; Kirley, P.D.; Alden, N.B.; Yousey-Hindes, K.; Anderson, E.J.; Ryan, P.; Kim, S.; Lynfield, R.; et al. Rates of Influenza-Associated Hospitalization, Intensive Care Unit Admission, and In-Hospital Death by Race and Ethnicity in the United States From 2009 to 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2121880.

- Artiga, S.; Hill, L. Racial Disparities in COVID-19 Impacts and Vaccinations for Children. KFF. 22 September 2021. Available online: https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-in-covid-19-impacts-and-vaccinations-for-children/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Hamdan, L.; Vandekar, S.; Spieker, A.J.; Rahman, H.; Ndi, D.; Shekarabi, E.S.; Thota, J.; A Rankin, D.; Haddadin, Z.; Markus, T.; et al. Epidemiological Trends of Racial Differences in Early- and Late-onset Group B Streptococcus Disease in Tennessee. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3634–e3640.

- Havers, F.P.; Delahoy, M.J.; Ujamaa, D.; Taylor, C.A.; Cummings, C.; Anglin, O.; Holstein, R.; Milucky, J.; O’Halloran, A.; Patel, K.; et al. Comparison of influenza and COVID-19-associated hospitalizations among children < 18 years old in the United States-FluSurv-NET (October-April 2017-2021) and COVID-NET (October 2020-September 2021). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, ciac388.