Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

A simple and efficient synthetic route to the novel 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H- and 4H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring systems from 3-(prop-2-en-1-yloxy)- or 3-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde oximes has been developed by employing the intramolecular nitrile oxide cycloaddition (INOC) reaction as the key step.

- pyrazole

- isoxazoline/isoxazole

- fused ring systems

- intramolecular nitrile oxide cycloaddition

- 4-pyrazolaldoximes 1JCH

- isoxazole 15N NMR

- isoxazoline 15N NMR

1. Introduction

The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of nitrile oxides as 1,3-dipoles and alkenes/alkynes as dipolarophiles has become an efficient tool in organic synthesis to obtain various substituted isoxazolines/isoxazoles [1][2][3]. The reaction was developed by Rolf Huisgen and described by Albert Padwa in their investigations on 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions [4][5]. Nitrile oxides, which are typically generated in situ, undergo subsequent 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition to form appropriate isoxazoles or isoxazolines. Numerous methods of nitrile oxide generation have been reported, mainly including the dehydration of nitroalkanes [6][7][8] and oxidation of aldoximes [9][10][11]. Alternatively, Svejstrupor described the synthesis of isoxazolines and isoxazoles from hydroxyimino acids via the visible-light-mediated generation of nitrile oxides by two sequential oxidative single electron transfer processes [12]. More recently, Chen et al. reported the synthesis of fully substituted isoxazoles from nitrile oxides, which were generated in situ from copper carbene and tert-butyl nitrite [13].

Notably, the intramolecular nitrile oxide cycloaddition (INOC) reaction can provide a route for the preparation of isoxazoles or isoxazolines annulated to various carbo- or heterocycles. For example, the intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of 2-phenoxybenzonitrile N-oxides to neighboring benzene rings, accompanied by dearomatization, formed the corresponding isoxazolines in high yields [14]. Recently, a method for the stereoselective synthesis of novel isoxazoline/isoxazole-fused indolizidine-, pyrrolizidine- and quinolizidine-based iminosugars has been developed, employing N-alkenyl/alkynyl iminosugar C-nitromethyl glycosides as nitrile oxide precursors in 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions [15]. The phthalate-tethered INOC strategy has also been described as a novel method for the synthesis of 12–15-membered chiral macrocycles having a bridged isoxazoline moiety in a highly regio- and diastereoselective manner [16]. Furthermore, diversity-oriented access to isoxazolino and isoxazolo benzazepines as possible bromodomain and extra-terminal motif protein (BET) inhibitors has been reported via a post-Ugi heteroannulation involving the intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of nitrile oxides with alkenes and alkynes [17]. In addition, an intramolecular 1,3-dipolar nitrile oxide cycloaddition strategy has been applied as an efficient synthesis protocol for the regio- and diastereoselective construction of highly functionalized tricyclic tetrahydroisoxazoloquinolines [18].

Fused isoxazoles or isoxazolines obtained by the INOC reaction may also serve as synthetically important intermediates for many biologically active compounds. Such compounds, including the HBV inhibitor entecavir [19][20], the antibiotic branimycin [21], the antiviral (+)-Brefeldin A [22], tricyclic isoxazoles combining serotonin (5-HT) reuptake inhibition with α2-adrenoceptor blocking activity [23] and the alkaloids meliacarpinin B [24] and Palhinine A [25], have been synthesized by employing INOC as a key step.

2. Synthesis

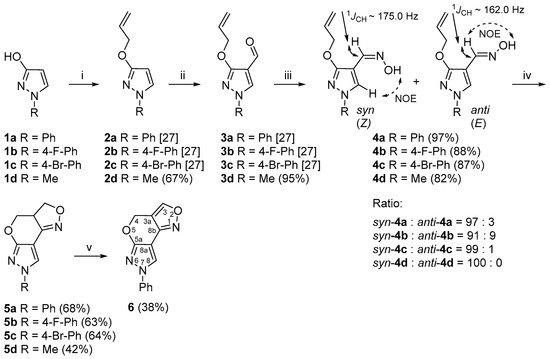

The synthetic strategy that researchers designed to construct the pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring system employs difunctional substrates (4a–d) that contain an aldoxime unit next to the allyloxy group attached to the pyrazole core and can serve as intermediates for nitrile oxide generation and subsequent cycloaddition (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthetic route for the 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring system. Reagents and conditions: (i) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 15 min, allylbromide, 60 °C, 1 h; (ii) DMF, POCl3, −10 °C, 15 min, 70 °C, 1 h; (iii) NH2OH·HCl, NaOAc, EtOH, reflux, 15 min; (iv) aq. NaOCl, DCM, rt, 1 h; (v) MnO2, toluene, reflux, 4 h.

As starting materials for the synthesis of compounds 4a–d, researchers used 1-phenyl-, 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-, 1-(4-bromophenyl)- and 1-methylpyrazol-3-ols (1a–d), which are readily accessible from the oxidation of appropriate pyrazolidin-3-ones [26]. The O-allylation of 1a–d with allylbromide in the presence of NaH gave O-allylated pyrazoles 2a–d [27]. To introduce a formyl group to the 4-position of the pyrazole ring, researchers employed a previously reported Vilsmeier–Haack reaction procedure [27][28]. Heating compounds 2a–d with Vilsmeier–Haack complex at 70 °C resulted in the formation of the desired pyrazole-4-carbaldehydes 3a–d (Scheme 1).

In order to prepare the 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole derivatives 5a–d by the INOC reaction, aldoximes 4a–d were synthesized by the treatment of 3a–d with hydroxylamine hydrochloride in the presence of sodium acetate [29]. As a result, the syn- and anti-3-allyloxy-4-pyrazolaldoximes were obtained in total yields of 82–97%. The 1H NMR spectra of aldoximes 4a–c showed the presence of two isomers in different ratios with a predominance of the syn isomer, while the compound 4d was obtained as a pure syn isomer.

Over the years, the isomerism of aldoximes has been thoroughly studied and many different NMR-based approaches have been developed, mainly due to the large differences in chemical shifts, coupling constants and distinct through-space connectivities in NOESY measurements of aldoxime syn-anti isomers [30]. The configurational assignment of aldoximes 4a–c was relatively easy due to the presence of both isomers, as it is well established that the resonance of the iminyl-H proton in the syn isomer is greatly shifted upfield by approximately δ 0.5–0.7 ppm in the 1H NMR spectra compared to the anti isomer [31]. Moreover, the 1D selective NOESY experimental data of aldoximes 4a–c showed that, upon irradiation of the hydroxyl proton N-OH of the predominant syn isomer, a strong positive NOE on the pyrazole 5-H proton was observed, while the minor isomer showed a positive NOE on the iminyl-H, therefore confirming the anti configuration. Finally, a heteronuclear 2D J-resolved NMR experiment was used in order to determine 1JCH coupling constants throughout the series of aldoximes. It is well established from previous studies that there is a large and constant difference between the magnitudes of 1JCH coupling constants of the iminyl moiety in syn-anti isomers [32], which is larger by at least 10–15 Hz for the syn isomer. The measurements of compounds 4a–c showed that the relevant 1JCH coupling constants of the iminyl moiety were around 175.0 Hz for the predominant syn isomer, while the minor anti isomer provided significantly lower coupling constant values by around 13.0 Hz. The configuration of aldoxime 4d as a pure syn isomer was easily deduced from NOESY measurements and the 1JCH coupling constant of the iminyl moiety, which was 174.5 Hz. The analysis of 15N NMR spectroscopic data showed highly consistent chemical shift values within each isomer, in a range from δ −18.2 to −25.7 ppm in the case of the syn isomer and in a range from δ −15.6 to −16.5 ppm for the anti isomer. A comparison of the relevant NMR data of aldoximes is presented in Table S1.

Several methods for the oxidation of aldoximes to nitrile oxides are known in the literature, including the application of oxidants such as chloramine T [33][34], N-halosuccinimides (NXS) [35][36][37], hypohalites [38][39][40], hypervalent iodine reagents [41][42][43] and oxone [44][45][46][47]. The reaction conditions for 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring formation were optimized by using 4a as a model compound (Table 1). When treating aldoxime 4a with chloramine T in EtOH at 50 °C for 30 min, the polycyclic product 5a was obtained in poor (20%) yield (Table 1, Entry 1). The intramolecular cyclization reaction of 4a in the presence of the aq. NaOCl in DCM gave the desired product 5a in 1 h in sufficient (68%) yield (Table 1, Entry 2). The experiment with TEA as an additive did not improve the yield of the product and 5a was obtained in 52% yield (Table 1, Entry 3). A similar result showing that no additional base is required to facilitate the cycloaddition was also observed by Roy and De in their investigation on the rate enhancement of nitrile oxide cyclization and, hence, rapid synthesis of isoxazolines and isoxazoles [48].

Table 1. Optimization of the INOC reaction conditions for 5a synthesis.

| Entry | Conditions | Yield *, % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chloramine T, EtOH, 50 °C, 30 min | 20 |

| 2 | 10% NaOCl, DCM, rt, 1 h | 68 |

| 3 | 10% NaOCl, TEA, DCM, rt, 3 h | 52 |

The optimized conditions (aq. NaOCl in DCM at rt) for 5a synthesis were also applied to the synthesis of 7-(4-fluorophenyl)-, 7-(4-bromophenyl)- and 7-methyl-3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazoles 5b–d to evaluate the scope of the methodology. The products were obtained in yields of 63%, 64% and 42%, respectively. In addition, researchers investigated whether the obtained 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole system can be further oxidized. Several oxidation reaction conditions were tested, e.g., 5a was stirred in DMSO at 110 °C in an open atmosphere [49] or treated with a catalytic amount of Pd/C in acetic acid [50]; the best result was obtained using activated MnO2 as an oxidant in toluene in a Dean–Stark apparatus for 4 h at reflux temperature [51]. Furthermore, 4H,7H-Pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole derivative 6 was formed in 38% yield.

A similar brief study on 5-chloropyrazole-4-carbaldehydes as synthons for intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition was also reported by L‘abbé et al. [52]. The authors noticed that 5-allyloxypyrazole-4-carbaldehyde derived from 5-chloropyrazole-4-carbaldehyde and further used as a precursor for intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions underwent a slow Claisen rearrangement to 4-allyl-5-hydroxypyrazole, even at room temperature. In contrast, researchers found 3-allyloxypyrazole-4-carbaldehydes to be stable. They can be stored in the laboratory at room temperature.

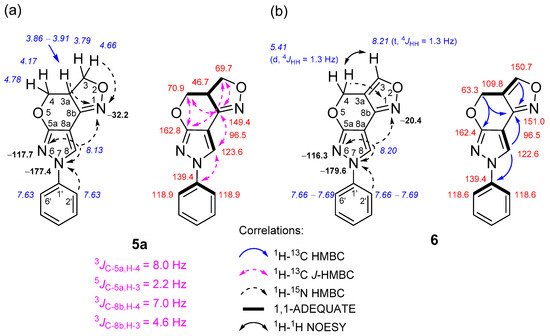

The formation of 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H- and 4H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring systems was easily deduced after an in-depth analysis of NMR spectral data, which were obtained through a combination of standard and advanced NMR spectroscopy techniques, such as 1H-13C HMBC, 1H-13C J-HMBC, 1H-15N HMBC, 1H-13C HSQC, 1H-13C H2BC, 1H-1H COSY, 1H-1H NOESY and 1,1-ADEQUATE experiments (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relevant 1H-13C HMBC, 1H-13C J-HMBC, 1H-15N HMBC, 1H-1H NOESY and 1,1-ADEQUATE correlations and 1H NMR (italics), 13C NMR and 15N NMR (bold) chemical shifts of compounds 5a (a) and 6 (b).

In the case of compound 5a, the multiplicity-edited 1H-13C HSQC spectrum allowed people to identify the pairs of geminally coupled methylene protons, since both protons displayed cross-peaks with the same carbon. For instance, it showed two pairs of negative signals at δH 4.66, 3.79 and 4.78, 4.17 ppm, which have one-bond connectivities with the methylene carbons C-3 (δ 69.7 ppm) and C-4 (δ 70.9 ppm), respectively. The chemical shifts of these methylene groups are expected to be similar and downfield compared to a neighboring methine group at site 3a, because both are bound to the oxygen atoms O-2 and O-5. This adjacent protonated carbon C-3a (δ 46.7 ppm) relative to the aforementioned methylene sites was easily assigned from an appropriate correlation in the 1H-13C H2BC spectrum.

In the 1H-15N HMBC spectrum of 5a, strong long-range correlations between the methylene 3-H proton at δ 4.66 ppm and the 3a-H proton at δ 3.86–3.91 ppm with the oxazole N-1 nitrogen at δ −32.2 ppm were observed. The lack of long-range correlations with another pair of methylene protons (δ 4.78, 4.17 ppm), and the aforementioned N-1 nitrogen, strongly hinted at assigning this methylene group to site 4. In order to unambiguously discriminate between these methylene groups, the 1H-13C heteronuclear couplings were measured using a 1H-13C J-HMBC experiment, thus providing complimentary evidence for correct structural assignment. The J-HMBC spectrum showed a strong correlation between the methylene proton δ 4.78 ppm and the quaternary carbon C-5a with an 8.0-hertz coupling constant, while the proton δ 4.66 ppm correlated very weakly, with a J value of only 2.2 Hz, which was attributed to a 5JC-5a, H-3. Finally, the pyrazole 8-H proton (δ 8.13 ppm) not only exhibited long-range HMBC correlations with neighboring N-7 “pyrrole-like” (δ −177.4 ppm) and N-6 “pyridine-like” (δ −117.7 ppm) nitrogen atoms, but also with the C-5a, C-8a and C-8b quaternary carbons, which were unambiguously assigned with the subsequent 1,1-ADEQUATE experiment, thus allowing all the heterocyclic moieties to be connected together. The structure of compounds 5b–d was determined by analogous NMR spectroscopy experiments, as described above. The skeleton of the pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring system contains three nitrogen atoms. The chemical shifts of the N-1, N-6 and N-7 atoms of compounds 5a–c were in a range from δ −30.9 to −32.2, δ −116.9 to −117.7 and δ −177.4 to −179.5 ppm, respectively, while in the case of compound 5d, which lacked a phenyl moiety at site 7, the chemical shifts of N-1, N-6 and N-7 atoms were δ −35.8, δ −112.3 and δ −194.4 ppm, respectively.

In the case of compound 6, a comparison of the 1H NMR spectra between 5a and 6 clearly indicated the disappearance of methine 3a-H (δ 3.86–3.91 ppm) and methylene 3-H protons (δ 4.66 and 3.79 ppm) and the formation of a new downfield methine 3-H proton signal at δ 8.21 ppm. The aforementioned methine proton that appeared as a triplet was mutually coupled with methylene 4-H protons (doublet, δ 5.41 ppm), as indicated by their meta-coupling (4JHH = 1.3 Hz). Moreover, a comparison between the 1H-1H COSY and 1H-1H NOESY spectra showed a complete absence of COSY cross-peaks between 3-H and 4-H and only strong NOEs, which confirmed their proximity in space. This finding strongly hinted at a neighboring quaternary carbon at site 3a, which was unambiguously assigned from 1,1-ADEQUATE spectral data, where the protonated carbons C-3 (δ 150.7 ppm) and C-4 (δ 63.3 ppm) showed a sole correlation with C-3a at δ 109.8 ppm. As expected, the 15N chemical shifts of N-6 (δ −116.3) and N-7 (δ −179.6) atoms were highly comparable to those of compounds 5a–c; only the N-1 atoms were slightly different and resonated at δ −20.4 ppm, which is in good agreement with the data reported in the literature [53].

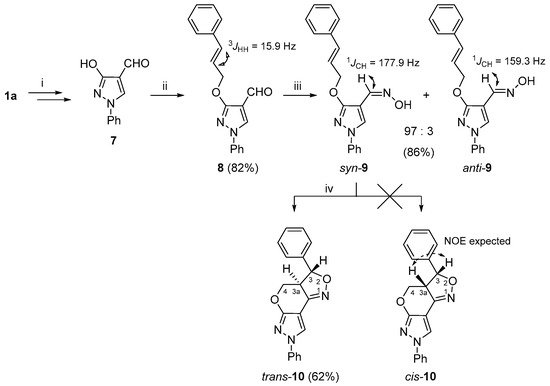

To expand the structural diversity of the obtained 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole system, researchers prepared additional vic-cinnamyloxy-oxime 9 as a substrate for the INOC reaction (Scheme 2). As the cinnamyloxy group turned out to be sensitive towards Vilsmeier–Haack reaction conditions, the O-alkylation formylation sequence of compound 1a successfully applied to the synthesis of 3-allyloxypyrazole-4-carbaldehydes 3a–d was reorganized. In short, first, the hydroxy group of pyrazol-3-ol (1a) was transformed to a benzyloxy group; then, the obtained 3-benzyloxypyrazole was formylated under the Vilsmeier–Haack reaction conditions, and the protecting OBn group was cleaved by TFA to give 3-hydroxy-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde 7 [28]. The latter compound was subjected to an alkylation reaction with cinnamyl chloride and the appropriate 3-cinnamyloxy-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehyde (8) was obtained in very good (82%) yield. A subsequent reaction of 8 with hydroxylamine gave the aldoxime 9, which was successfully used for the INOC reaction, and 3-phenyl-3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole trans-10 was obtained with a fair (62%) yield.

Scheme 2. Synthetic route for the 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole 10. Reagents and conditions: (i) in accordance to ref. [28]; (ii) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 15 min, cinnamyl chloride, 60 °C, 15 min; (iii) NH2OH·HCl, NaOAc, EtOH, reflux, 15 min; (iv) NaOCl, DCM, rt, 1 h.

While the structural elucidation of compound trans-10 was straightforward and followed the same logical approach as in the case of compounds 5a–d and 6, determination of the relative configuration at C-3 and C-3a proved to be a more challenging task and was achieved by combined analysis of NOESY, J-coupling and molecular modeling data. For instance, the initial geometry optimizations were performed using MM2 and MMFF94 force fields [54], followed by DFT methods using B3LYP/def2-TZVP, as implemented in ORCA 5.0.0 [55], which provided the dihedral angle values between H-C(3)-C(3a)-H for structures trans-10 (154.34°) and cis-10 (19.28°). Then, the theoretical 1H-1H coupling constants were calculated with the same software package following a standard procedure using a B3LYP/PCSSEG-2 basis set. The dihedral angle values were used in the calculation of 3JH3,H3a by the Haasnoot–de Leeuw–Altona (HLA) equation [56]. The 3JH3,H3a values estimated by the HLA method were 10.0 Hz for trans-10 and 8.2 Hz for cis-10, while ORCA 5.0.0 calculations were 13.4 and 10.8 Hz, respectively. The experimental value 13.1 Hz, which was obtained from the 1H NMR spectrum, hinted in favor of the trans-10 structure. A highly similar class of heterocycles, naphthopyranoisoxazolines, were synthesized by Liaskopoulos et al. [57], where the target compounds possessed a trans configuration, as confirmed by X-ray and NMR analyses, and their 3JH3,H3a values were in the range of 12.2–12.5 Hz. Finally, unambiguous confirmation of trans-10 assignment was obtained from the 1H-1H NOESY spectrum, as it was evident from the geometrically optimized structures (Figures S80 and S81) that, in the case of cis-10, there should be a strong NOE between protons 3-H and 3a-H, while the NOE between 3a-H and the neighboring 3-phenyl group aromatic protons is not possible. However, in this case, the 1H-1H NOESY spectrum showed completely opposite measurements. Moreover, a distinct NOE between protons 3-H/4-Ha and 3a-H/4-Hb is only possible if the relative configuration is trans-10.

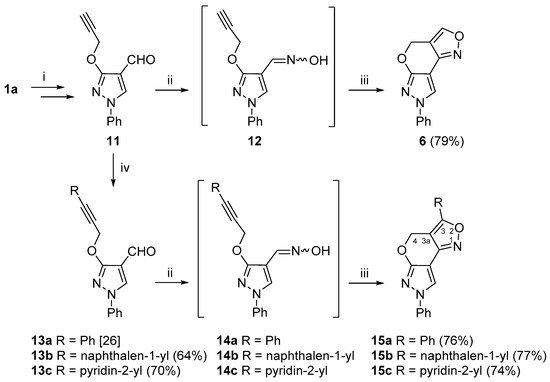

Researchers also investigated the INOC reaction of vic–alkyne–oxime substrates 12 and 14a–c (Scheme 3). To obtain the intermediate compound 12, firstly, 3-hydroxypyrazole 1a was O-propargylated and formylated to give carbaldehyde 11 [58]. Compound 11 was then successfully converted to 4H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole 6 via the INOC reaction of intermediate oxime 12, and the targeted new polyheterocyclic compound 6 was obtained in good (79%) yield. In addition, alkyne 11 was further subjected to the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction with various (het)arylhalides, i.e., iodobenzene, 1-iodonaphthalene and 2-bromopyridine, under the standard Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction conditions (Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, DMF, 60 °C, argon atmosphere) to give alkynes 13a–c in good yields [58]. Compounds 13a–c were further treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride to provide aldoximes 14a–c, which were used in the INOC reaction without further purification. Aldoxime 14a was subjected to a detailed NMR analysis, and, to delight, it was obtained as a pure syn isomer, which was easily elucidated from a 1JCH coupling constant of the iminyl moiety, which was 179.2 Hz. Moreover, 4H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazoles 15a–c were obtained in good yields.

Scheme 3. Synthetic route for the 4H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazole ring system. Reagents and conditions: (i) in accordance to ref. [58]; (ii) NH2OH·HCl, NaOAc, EtOH, reflux, 15 min; (iii) NaOCl, DCM, rt, 1 h; (iv) RX, Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, TEA, DMF, 60 °C, 15 min.

As expected, the chemical shifts of the 3-aryl-substituted compounds 15a–c were highly similar to those of compound 6. A distinct difference in the 1H NMR spectra of the aforementioned compounds was that they contained only a singlet for the methylene 4-H protons in the area of δ 5.32–6.03 ppm, which indicated the lack of coupling partners. The data from the 1H-13C HMBC spectra revealed a distinct long-range correlation between the aforementioned methylene protons and a quaternary carbon at site 3. Moreover, the protons from a neighboring 3-aryl moiety shared an HMBC cross-peak with carbon C-3 as well, thus allowing different structural fragments to be joined together. The chemical shifts of the N-1, N-6 and N-7 atoms of 3-aryl-substituted compounds were in ranges of δ −23.9 to −25.0, δ −116.4 to −117.4 and δ −179.6 to −180.1 ppm, respectively, while, in the case of compound 15c with a pyridin-2-yl moiety, the pyridine nitrogen resonated at δ −72.8 ppm.

3. Conclusions

This entry has developed a convenient method for the preparation of 3a,4-dihydro-3H,7H- and 4H,7H-pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazoles from easily obtainable 3-(prop-2-en-1-yloxy)- or 3-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehydes by INOC reaction of intermediate oximes. The key stage—nitrile oxide preparation from the corresponding aldoximes—was carried out by oxidation with sodium hypochlorite. The method was applied for the synthesis of pyrazolo[4′,3′:5,6]pyrano[4,3-c][1,2]oxazoles with various substituents in the third or seventh position. In addition, extensive NMR spectroscopic studies have been undertaken using standard and advanced methods to unambiguously determine the configuration of intermediate aldoximes, showing the predomination of the syn-isomer, as well as the structure of new polycyclic systems.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules26185604

References

- Browder, C.C. Recent Advances in Intramolecular Nitrile Oxide Cycloadditions in the Synthesis of 2-Isoxazolines. Curr. Org. Synth. 2011, 8, 628–644.

- Plumet, J. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions of Nitrile Oxides under “Non-Conventional” Conditions: Green Solvents, Irradiation, and Continuous Flow. ChemPlusChem 2020, 85, 2252–2271.

- Roscales, S.; Plumet, J. Mini-Review: Organic Catalysts in the 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions of Nitrile Oxides. Heterocycles 2019, 99, 725–744.

- Huisgen, R. Cycloadditions—Definition, Classification, and Characterization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1968, 7, 321–328.

- Padwa, A. Intramolecular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1976, 15, 123–136.

- Maugein, N.; Wagner, A.; Mioskowski, C. New conditions for the generation of nitrile oxides from primary nitroalkanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 1547–1550.

- Chen, W.C.; Kavala, V.; Shih, Y.H.; Wang, Y.H.; Kuo, C.W.; Yang, T.H.; Huang, C.Y.; Chiu, H.H.; Yao, C.F. Synthesis of Bicyclic Isoxazoles and Isoxazolines via Intramolecular Nitrile Oxide Cycloaddition. Molecules 2015, 20, 10910–10927.

- Reja, R.M.; Sunny, S.; Gopi, H.N. Chemoselective Nitrile Oxide−Alkyne 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reactions from Nitroalkane-Tethered Peptides. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 3572–3575.

- Singhal, A.; Parumala, S.K.R.; Sharma, A.; Peddinti, R.K. Hypervalent iodine mediated synthesis of di- and tri-substituted isoxazoles via cycloaddition of nitrile oxides. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 719–722.

- Zhang, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, E.; Yi, R.; Chen, C.; Yu, L.; Xu, Q. Pd/Mn Bimetallic Relay Catalysis for Aerobic Aldoxime Dehydration to Nitriles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 784–790.

- Wade, P.A. Additions to and Substitutions at CC π-Bonds. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Trost, B.M., Fleming, I., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

- Svejstrup, T.D.; Zawodny, W.; Douglas, J.J.; Bidgeli, D.; Sheikh, N.S.; Leonori, D. Visible-light-mediated generation of nitrile oxides for the photoredox synthesis of isoxazolines and isoxazoles. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12302–12305.

- Chen, R.; Ogunlana, A.A.; Fang, S.; Long, W.; Sun, H.; Bao, X.; Wan, X. In situ generation of nitrile oxides from copper carbene and tert-butyl nitrite: Synthesis of fully substituted isoxazoles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 4683–4687.

- Yonekawa, M.; Koyama, Y.; Kuwata, S.; Takata, T. Intramolecular 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Nitrile N-Oxide Accompanied by Dearomatization. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 1164–1167.

- Prasad, S.S.; Baskaran, S. Iminosugar C-Nitromethyl Glycoside: Stereoselective Synthesis of Isoxazoline and Isoxazole-Fused Bicyclic Iminosugars. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 1558–1564.

- Majumdar, S.; Hossain, J.; Natarajan, R.; Banerjee, A.K.; Maiti, D.K. Phthalate tethered strategy: Carbohydrate nitrile oxide cycloaddition to 12–15 member chiral macrocycles with alkenyl chain length controlled orientation of bridged isoxazolines. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 106289–106293.

- Balalaie, S.; Shamakli, M.; Nikbakht, A.; Alavijeh, N.S.; Rominger, F.; Rostamizadeh, S.; Bijanzadeh, H.R. Direct access to isoxazolino and isoxazolo benzazepines from 2-((hydroxyimino)methyl)benzoic acid via a post-Ugi heteroannulation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 5737–5742.

- Bakthadoss, M.; Vinayagam, V. A novel protocol for the facile construction of tetrahydroquinoline fused tricyclic frameworks via an intramolecular 1,3-dipolar nitrile oxide cycloaddition reaction. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 10007–10014.

- Gioti, E.G.; Koftis, T.V.; Neokosmidis, E.; Vastardi, E.; Kotoulas, S.S.; Trakossas, S.; Tsatsas, T.; Anagnostaki, E.E.; Panagiotidis, T.D.; Zacharis, C.; et al. A new scalable synthesis of entecavir. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 519–527.

- Zhou, B.; Li, Y. Synthesis of Entecavir (BMS-200475). Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 502–504.

- Mulzer, J.; Castagnolo, D.; Felzmann, W.; Marchart, S.; Pilger, C.; Enev, V.S. Toward the Synthesis of the Antibiotic Branimycin: Novel Approaches to Highly Substituted cis-Decalin Systems. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 5992–6001.

- Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Shim, P.J.; Lim, J.I.; Doi, T.; Kim, S. Role of Conformational Effects on the Regioselectivity of Macrocyclic INOC Reactions: Two New Asymmetric Total Syntheses of (+)-Brefeldin A. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 772–781.

- Andrés, J.I.; Alcázar, J.; Alonso, J.M.; Alvarez, R.M.; Bakker, M.H.; Biesmans, I.; Cid, J.M.; De Lucas, A.I.; Fernández, J.; Font, L.M.; et al. Discovery of a New Series of Centrally Active Tricyclic Isoxazoles Combining Serotonin (5-HT) Reuptake Inhibition with α2-Adrenoceptor Blocking Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 2054–2071.

- Dong, C.; Qiao, T.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ao, J.; Liang, G. Rapid construction of the ABD tricyclic skeleton in meliacarpinin B from carvone enabled by an INOC strategy. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 1890–1894.

- Gaugele, D.; Maier, M.E. Synthesis of the Core Structure of Palhinine A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 2549–2556.

- O’Brien, D.F.; Gates, J.W., Jr. Some Reactions of 3-Hydroxy-1-phenylpyrazole. J. Org. Chem. 1966, 31, 1538–1542.

- Bieliauskas, A.; Krikštolaitytė, S.; Holzer, W.; Šačkus, A. Ring-closing metathesis as a key step to construct the 2,6-dihydropyranopyrazole ring system. Arkivoc 2018, 2018, 296–307.

- Arbačiauskienė, E.; Martynaitis, V.; Krikštolaitytė, S.; Holzer, W.; Šačkus, A. Synthesis of 3-substituted 1-phenyl-1H-pyrazole-4-carbaldehydes and the corresponding ethanones by Pd-catalysed cross-coupling reactions. Arkivoc 2011, 11, 1–21.

- Sankar, B.; Harikrishnan, M.; Raja, R.; Sadhasivam, V.; Malini, N.; Murugesan, S.; Siva, A. Design of a simple and efficient synthesis for bioactive novel pyrazolyl–isoxazoline hybrids. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 10458–10467.

- Heinisch, G.; Holzer, W. Convenient and rapid determination of the configuration of aldoximes and ketoximes by means of NOE difference spectroscopy. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 3109–3112.

- Rykowski, A.; Guzik, E.; Makosza, M.; Holzer, W. Configurational assignments of oximes derived from 5-formyl and 5-acyl-1,2,4-triazines. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1993, 30, 413–418.

- Fraser, R.R.; Capoor, R.; Bovenkamp, J.W.; Lacroix, B.; Pagotto, J. The use of shift reagents and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance for assignment of stereochemistry to oximes. Can. J. Chem. 1984, 61, 2616–2620.

- Hansen, T.V.; Wu, P.; Fokin, V.V. One-Pot Copper(I)-Catalyzed Synthesis of 3,5-Disubstituted Isoxazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 7761–7764.

- Padmavathi, V.; Reddy, K.V.; Padmaja, A.; Venugopalan, P. Unusual Reaction of Chloramine-T with Araldoximes. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 1567–1570.

- Ledovskaya, M.S.; Rodygin, K.S.; Ananikov, V.P. Calcium-mediated one-pot preparation of isoxazoles with deuterium incorporation. Org. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 226–231.

- Boruah, M.; Konwar, D. KF/Al2O3: Solid-Supported Reagent Used in 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Reaction of Nitrile Oxide. Synth. Comm. 2012, 42, 3261–3268.

- Isaacman, M.J.; Cui, W.; Theogarajan, L.S. Rapid metal-free macromolecular coupling via In Situ nitrile oxide-activated alkene cycloaddition. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 3134–3141.

- Minakata, S.; Okumura, S.; Nagamachi, T.; Takeda, Y. Generation of Nitrile Oxides from Oximes Using t-BuOI and Their Cycloaddition. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2966–2969.

- Chiacchio, U.; Corsaro, A.; Rescifina, A.; Bkaithan, M.; Grassi, G.; Piperno, A.; Privitera, T.; Romeo, G. Stereoselective synthesis of homochiral annulated sultams via intramolecular cycloaddition reactions. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3425–3433.

- Ravula, S.; Bobbala, R.R.; Kolli, B. Synthesis of novel isoxazole functionalized pyrazolopyridine derivatives; their anticancer activity. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2020, 57, 2535–2538.

- Mendelsohn, B.A.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Teyssier, F.; Aulakh, V.S.; Ciufolini, M.A. Oxidation of Oximes to Nitrile Oxides with Hypervalent Iodine Reagents. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1539–1542.

- Yoshimura, A.; Jarvi, M.E.; Shea, M.T.; Makitalo, C.L.; Rohde, G.T.; Yusubov, M.S.; Saito, A.; Zhdankin, V.V. Hypervalent Iodine(III) Reagent Mediated Regioselective Cycloaddition of Aldoximes with Enaminones. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 39, 6682–6689.

- Jawalekar, A.M.; Reubsaet, E.; Rutjes, F.P.J.T.; van Delft, F.L. Synthesis of isoxazoles by hypervalent iodine-induced cycloaddition of nitrile oxides to alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3198–3200.

- Zhao, G.; Liang, L.; Wen, C.H.E.; Tong, R. In Situ Generation of Nitrile Oxides from NaCl–Oxone Oxidation of Various Aldoximes and Their 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 315–319.

- Han, L.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, M.; Yan, J. An environmentally benign synthesis of isoxazolines and isoxazoles mediated by potassium chloride in water. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 2308–2311.

- Yoshimura, A.; Zhu, C.; Middleton, K.R.; Todora, A.D.; Kastern, B.J.; Maskaev, A.V.; Zhdankin, V.V. Hypoiodite mediated synthesis of isoxazolines from aldoximes and alkenes using catalytic KI and Oxone as the terminal oxidant. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 4800–4802.

- Xiang, C.; Li, T.; Yan, J. Hypervalent Iodine–Catalyzed Cycloaddition of Nitrile Oxides to Alkenes. Synth. Comm. 2014, 44, 682–688.

- Roy, B.; De, R.N. Enhanced rate of intramolecular nitrile oxide cycloaddition and rapid synthesis of isoxazoles and isoxazolines. Monatsh. Chem. 2010, 141, 763–771.

- Jenkins, R.N.; Hinnant, G.M.; Bean, A.C.; Stephens, C.E. Aerobic aromatization of 1,3,5-triarylpyrazolines in open air and without catalyst. Arkivoc 2015, 7, 347–353.

- Nakamichi, N.; Kawashita, Y.; Hayashi, M. Oxidative Aromatization of 1,3,5-Trisubstituted Pyrazolines and Hantzsch 1,4-Dihydropyridines by Pd/C in Acetic Acid. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 3955–3957.

- Vilela, G.D.; da Rosa, R.R.; Schneider, P.H.; Bechtold, I.H.; Eccher, J.; Merlo, A.A. Expeditious preparation of isoxazoles from Δ2-isoxazolines as advanced intermediates for functional materials. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 6569–6572.

- L’abbé, G.; Emmers, S.; Dehaen, W.; Dyall, L.K. 5-Chloropyrazole-4-carbaldehydes as synthons for intramolecular 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1994, 2553–2558.

- Christl, M.; Warren, J.P.; Hawkins, B.L.; Roberts, J.D. Carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of nitrile oxides and related reaction products. Unexpected carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic resonance parameters of 2,4,6-trimethylbenzonitrile oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973, 95, 4392–4397.

- Lewis-Atwell, T.; Townsend, P.A.; Grayson, M.N. Comparisons of different force fields in conformational analysis and searching of organic molecules: A review. Tetrahedron 2021, 79, 131865.

- Neese, F. Software update: The ORCAprogram system, version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2018, 8, e1327.

- Haasnoot, C.A.G.; de Leeuw, F.A.A.M.; Altona, C. The relationship between proton-proton NMR coupling constants and substituent electronegativities—I: An empirical generalization of the karplus equation. Tetrahedron 1980, 36, 2783–2792.

- Liaskopoulos, T.; Skoulika, S.; Tsoungas, P.G.; Varvounis, G. Novel Synthesis of Naphthopyranoisoxazoles and Versatile Access to Naphthopyranoisoxazolines. Synthesis 2008, 711–718.

- Arbačiauskienė, E.; Laukaitytė, V.; Holzer, W.; Šačkus, A. Metal-Free Intramolecular Alkyne-Azide Cycloaddition To Construct the Pyrazolotriazolooxazepine Ring System. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 5663–5670.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!