Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is uniquely poised for advanced imaging in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract as it allows real-time, subsurface and wide-field evaluation at near-microscopic resolution, which may improve the current limitations or even obviate the need of superficial random biopsies in the surveillance of early neoplasias in the near future. OCT’s greatest impact so far in the GI tract has been in the study of the tubular esophagus owing to its accessibility, less bends and folds and allowance of balloon employment with optimal contact to aid circumferential imaging. Moreover, given the alarming rise in the incidence of Barrett's esophagus and its progression to adenocarcinoma in the U.S., OCT has helped identify pathological features that may guide future therapy and follow-up strategy. This review will explore the current uses of OCT in the gastrointestinal tract and future directions, particularly with non-endoscopic office-based capsule OCT and the use of artificial intelligence to aid in diagnoses.

- gastrointestinal imaging

- optical coherence tomography

- Barrett’s esophagus

- artificial intelligence

- cancer detection

- colon cancer

- OCT

1. Introduction

Diagnostic imaging of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract has long relied on white-light endoscopy (WLE) for the detection of mucosal abnormalities such as neoplasias, vascular deformities, and inflammatory conditions. While WLE is a clinical standard for GI imaging and cancer detection, it remains far from ideal. A standard colonoscopy can miss up to 40% of adenomas [1][2] and despite improvements to increase mucosal visualization [3], miss rates are still concerning, especially for flat lesions such as sessile serrated adenomas [4]. While part of the suboptimal detection can be attributed to patients' inadequate preparatory colonic lavage, WLE's limited field of view (FOV) and time-consuming mucosal inspection during endoscope withdrawal are additional limiting factors [3]. Since the survival rate from GI cancers can be improved by 5 to 10-fold if diagnosed at an early stage [5], there is an obvious need to improve detection of early GI neoplasias.

Advanced imaging in the GI tract can be broadly divided into surface and subsurface modalities. Surface imaging includes chromoendoscopy [6], virtual chromoendoscopy [7], magnification endoscopy and endocytoscopy [8], and autofluorescence imaging [9]. There have been tremendous improvements in the resolution, field of view (FOV), and methods of surface imaging, such as improving contrast in magnification endoscopy and using selected wavelengths (Narrow Band Imaging, NBI) or digital enhancements such as flexible spectral imaging color enhancement (FICE; Fujinon Inc, Saitama, Japan). However, these modalities are limited to superficial lesions and improved magnification generally comes at the cost of restricted FOV, which makes screening and surveillance for multi-focal lesions more difficult.

On the other hand, subsurface imaging, which includes endoscopic ultrasonography [10], confocal endomicroscopy [11], and OCT, allows for visualization of structures not feasible with most endoscopes. Of these technologies, OCT is a uniquely poised imaging modality, combining nearly microscopic resolution with volumetric and subsurface real-time imaging capabilities [12]. These characteristics position OCT to solve many of the weaknesses of the other GI tract imaging techniques.

2. Evolving OCT Technology

Briefly, the working principle of OCT is analogous to that of an ultrasound, with analysis of reflected light rather than sound waves. An optical ranging technique called low coherence interferometry [13][14] uses a Michelson interferometer to measure the time delay and subsequent signal intensity of light reflected from a tissue sample. Since its first publication in the early 1990s [15], endoscopic OCT techniques [16] and applications have become major areas of research [17][18][19][20].

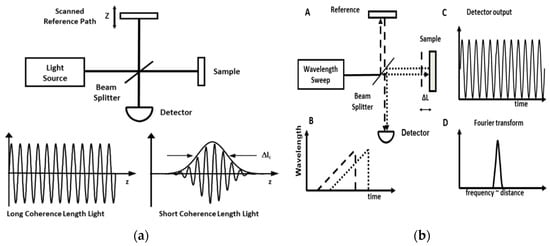

OCT can be broadly divided into two types: time-domain OCT (TD-OCT) and Fourier-domain OCT (FD-OCT). They differ in that TD-OCT considers each scan individually with a moving mirror (Figure 1a) [21][22][23], while FD-OCT applies a Fourier transform on the detected spectrum (Figure 1b) [24][25][26]. FD-OCT's introduction in the early 2000s generated a great increase in imaging speed and sensitivity of OCT [23][24][25][26]. FD-OCT can be further divided into subcategories, spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) and swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) [21]. SD-OCT uses a spectrometer with a broadband light source and typically operates at shorter wavelengths [27][28]. SS-OCT measures interference spectra using a wavelength-swept light source and a photodetector, operating at longer wavelengths and with a high imaging frequency, sometimes reaching the MHz region [29][30][31]. Due to its improved tissue depth penetration at longer wavelengths, SS-OCT is the technology of choice for endoscopic applications [32][33].

Figure 1. (a) Time-domain optical coherence tomography (TD-OCT) uses low coherence interferometry. The light source is split and the backscattered light is captured by the detector. The depth information is provided by the scanned reference path. Adapted from Tsai et al. 2014. (b). Swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) allows 10–200-fold faster imaging compared to TD-OCT. (A) Interferometer with swept laser source and beam splitter and path difference ΔL. (B) Time delay of light from sample (dotted) and reference light (dashed). (C) Interference signal proportional to delay. (D) Fourier transform of the interference signal measures ΔL. Figure and caption adapted from Tsai et al. 2014.

3. OCT Applications in the GI Tract

3.1. Esophagus

Barrett's Esophagus (BE) is the main precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). EAC is the eighth most common cancer type in the world, and despite falling incidence rates of squamous cell carcinoma, the incidence of EAC continues to rise globally, especially in western countries (--including the United States) [34][35]. Alarmingly, its incidence increased 6.5-fold from 1975-2009 according to SEER data [36], making the incidence for EAC one of the fastest rising of all cancers in the US, particularly in the white male population [37]. EAC is thought to arise stepwise from specialized intestinal metaplasia (SIM) to low grade dysplasia (LGD), high grade dysplasia (HGD) and then intramucosal carcinoma (IMC) [38][39]. Guidance for surveillance of BE neoplastic progression has been provided by the Seattle Protocol, which advocates for targeted biopsies or resection of suspicious esophageal areas followed by random four-quadrant biopsies at set intervals [40]. This sampling limits itself to less than 5% of the esophageal surface area [12]. Pinch biopsies often do not acquire deeper structures and one study showed they miss the lamina propria more than 60% of the time [41][42], raising concerns regarding under-sampling for the often focal and small areas of dysplasia. Additionally, after ablation, residual BE tissues may become buried under the neosquamous epithelium as subsquamous intestinal metaplasia (SSIM) and elude detection [43].

Given these needs and the relative simplicity of a tubular structure for OCT imaging, OCT in the GI tract has been applied largely to the esophagus. OCT, with its volumetric, subsurface and near-microscopic imaging, is positioned to help the diagnostic yield of biopsies or even obviate biopsies if it can demonstrate sufficient sensitivity and specificity according the Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations (PIVI) standards from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. In order to eliminate random mucosal biopsies in BE patients, PIVI recommends that an imaging technology with targeted biopsies should have a per-patient sensitivity of at least 90% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of at least 98% for detecting high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or early esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) [12][44].

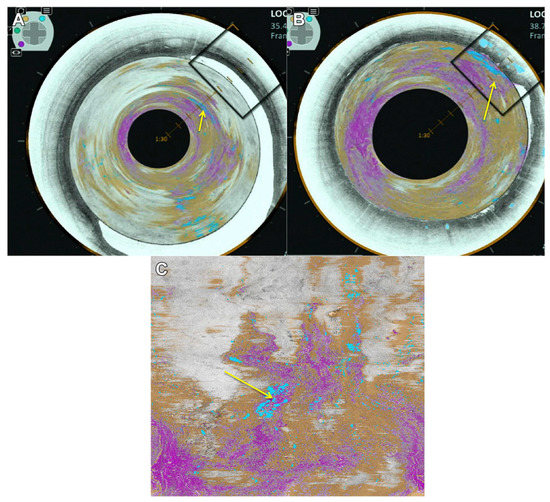

In the esophagus, Evans et al. showed that OCT could differentiate IMC and HGD from LGD, intermediate-grade dysplasia (IGD) and SIM without dysplasia at the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) (Evans 2006) [45]. The endoscopic balloon-centering catheter [46] laid the foundation for the commercialization of a GI-focused OCT system (called volumetric laser endomicroscopy, or VLE; NvisionVLE® Imaging System, Ninepoint Medical) [47]. VLE provides real-time volumetric scans with ~3 mm imaging depth and 7 μum axial resolution over a 6 cm stretch of the esophageal inner wall (Figure 2). As will be discussed below, VLE can be used with diagnostic algorithms to detect dysplasia [48] and laser-marking for more precise targeting and co-registry of images with biopsies and better delineation of areas for ablation [49][50]. Similar promising OCT imaging systems are emerging for GI applications including LuminScan ™ (Micro-Tech, Nanjing, CN). On the other hand, imaging probes introduced without balloons may be helpful in real-time imaging during biopsies and may help delineate lateral margins during endoscopic resections [51].

Figure 2. Volumetric laser endomicroscopy (VLE) of the esophagus showing a luminal en face view of an area of overlap (yellow arrow) between the 3 features of dysplasia (orange is lack of layering, blue is glandular structures and pink is a hyper-reflective surface). (A) A view looking down from the proximal esophagus. (B) A view closer to the suspected area of dysplasia. The en face view is also shown (C). Figure and caption adapted from Trindade et al. 2019.

3.2. Colon

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a major cause of death in the US and the second leading cause of cancer death with an estimated 145,600 new cases and an estimated 51,020 deaths for 2019 [52]. The survival rate from GI cancers can be improved by 5- to 10-fold if diagnosed at an early stage [5]. The current recommendation in the US is to screen all individuals at age 45 or earlier if deemed at higher risk for CRC based on certain conditions or family history using specific stool tests, radiological exams or direct visualization by colonoscopy [53]. Colonoscopy allows for the removal of suspect adenomatous lesions but can be time-consuming and has miss rates in the range of 17 to 28% [54]. Thus, advanced imaging modalities could help improve detection. OCT has been demonstrated to differentiate colorectal cancer from adenomatous polyps [55][56], and its ability to reveal the submucosa may allow more nuanced polyp treatments. For example, OCT showed normal submucosa underneath a rectal polyp near the dentate line and altered its management from a full thickness resection to a less invasive endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) [57]. High-resolution en face colon images from OCT are analogous to the traditional magnified endoscopic view, but do not require contrast agents; they also yield clinically powerful multi-depth visibility [58]. Thus, OCT has the potential to improve polyp detection and management.

3.3. Hepatobiliary

Hepatobiliary malignancies account for around 13% of global cancer mortalities and 3% of those in the US, with cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) accounting for 15-20% of hepatobiliary malignancies [59]. The assessment of strictures in the pancreatico-biliary tract can be challenging since they can be benign or cancerous. The current protocol is an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and random biopsies or brush cytology [60][61], but the practice often leads to a low diagnostic yield because of the small amount of available tissue and the tortuous anatomy of the bile duct [62][63]. Thus, a low-profile OCT probe was designed to enable passage through the pancreatic duct and demonstrated the ability to differentiate malignant from benign strictures [64][65][66]. Tyberg et al. described that strictures with cholangiocarcinoma showed a hyperreflective surface with loss of inner wall layering, while benign areas had clear delineated ductal wall layering [67]. Joshi, in a 22-patient study, found similar results and was able to quantify the thickness of each duct layer to differentiate benign, inflammatory and malignant tissue types [68]. This ability of OCT to potentially differentiate benign from cancerous lesions may obviate the need to remove tissue in the future.

3.4. Imaging of Microvasculature

In 2014, Tsai et al. demonstrated a 3D OCT angiography (OCT-A) using the biospeckle effect to reveal the subsurface vasculature of BE without exogenous contrast agents [69]. A video introduction of this promising technology in the gastrointestinal tract is available [70]. Revelation of subsurface vasculature could be clinically useful in order to highlight areas to minimize bleeding during an APC hybrid lift ablation (Erbe Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany) or peroral endoscopic myotomy, for example. Microvasculature irregularities also appear to be correlated with dysplasia in BE [71][72].

Additionally, OCT-A may help identify specific areas to treat in the rectal wall of chronic radiation proctopathy (CRP) which may develop consequent to pelvic irradiation for various malignancies [73][74]. OCT also may help identify other vascular abnormalities such as Dieulafoy's lesions, often buried deeply in the submucosal architecture and a source for intermittent but brisk blood loss [75]. Additionally, en face OCT findings have been studied in patients with gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), also a cause of upper GI bleeding, before and after RFA treatment. Lee et al. demonstrated OCT/OCT angiography's (OCTA's) ability to differentiate GAVE-associated tissue architecture and microvasculature before and after RFA, namely identifying regions of incomplete ablation hidden under coagulum [76]. Lastly, instantaneous real-time imaging may be used in the future to assess vascular changes associated with food allergies in the gut that are increasingly appreciated as potential causes of diarrhea or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

3.5. Small Intestine

The length, tortuous anatomy and folds in the small intestine pose particularly difficult challenges for OCT imaging in the GI tract. Nonetheless, several papers show successful utility of OCT. Masci et al. demonstrated OCT's ability to differentiate celiac disease based on villous atrophy [77][78], while Kamboj et al. used OCT to reveal the submucosal mass of a duodenal neuroendocrine tumor (NET) [79]. Additionally, Lee et al. used ultrahigh-speed endoscopic OCT to study the structural differences of Crohn's disease in the terminal ileum (TI), showing that TI with Crohn's ileitis exhibited irregular mucosal patterns and enlarged villous internal structures [80].

4. Conclution

OCT is a rapid, volumetric, nearly microscopically resolved, subsurface endoscopic imaging modality that addresses many of the pitfalls associated with WLE and NBI. OCT has been rigorously studied in the esophagus due to its tubular anatomy and is starting to gain traction throughout the rest of the GI tract including the stomach, small intestine and colon. OCT is compatible with a fleet of accessories including laser markers, autofluorescence techniques and the traditional acoustic ultrasound. Additionally, OCT has the potential to be performed using an office-based capsule, negating the need for the burdens of sedation. Given the copious amounts of data produced by OCT, it is also a promising platform for the implementation of machine learning to achieve a level of autodetection akin to or even surpassing that of the skilled endoscopist. While machine learning in OCT still has a long way to go before it reaches such a skillful level, it can nonetheless play the role of second reader. The plethora of benefits from OCT, including accessorization, ease of delivery and machine learning, uniquely position this technology to address the disease burden of gastrointestinal maladies.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app9152991

References

- Seward, E.; Lumley, S. Endoscopy provision: Meeting the challenges. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2017, 8, 90.

- Kurniawan, N.; Keuchel, M. Flexible Gastro-intestinal Endoscopy—Clinical Challenges and Technical Achievements. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 168–179.

- Bond, A.; Sarkar, S. New technologies and techniques to improve adenoma detection in colonoscopy. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 7, 969–980.

- Groff, R.J.; Nash, R.; Ahnen, D.J. Significance of serrated polyps of the colon. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2008, 10, 490–498.

- A.C. Cancer Facts and Figures—2017. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2017.html. (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Song, L.M.W.K.; Adler, D.G.; Chand, B.; Conway, J.D.; Croffie, J.M.B.; DiSario, J.A.; Mishkin, D.S.; Shah, R.J.; Somogyi, L.; Tierney, W.M. Chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 66, 639–649.

- Manfredi, M.A.; Dayyeh, B.K.A.; Bhat, Y.M.; Chauhan, S.S.; Gottlieb, K.T.; Hwang, J.H.; Komanduri, S.; Konda, V.; Lo, S.K.; Maple, J.T. Electronic chromoendoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 249–261.

- Kiesslich, R.; Jung, M. Magnification endoscopy: Does it improve mucosal surface analysis for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal neoplasias? Endoscopy 2002, 34, 819–822.

- Song, L.-M.W.K.; Banerjee, S.; Desilets, D.; Diehl, D.L.; Farraye, F.A.; Kaul, V.; Kethu, S.R.; Kwon, R.S.; Mamula, P.; Pedrosa, M.C. Autofluorescence imaging. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011, 73, 647–650.

- Zuccaro, G.; Gladkova, N.; Vargo, J.; Feldchtein, F.; Zagaynova, E.; Conwell, D.; Falk, G.; Goldblum, J.; Dumot, J.; Ponsky, J. Optical coherence tomography of the esophagus and proximal stomach in health and disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 2633.

- Chauhan, S.S.; Dayyeh, B.K.A.; Bhat, Y.M.; Gottlieb, K.T.; Hwang, J.H.; Komanduri, S.; Konda, V.; Lo, S.K.; Manfredi, M.A.; Maple, J.T. Confocal laser endomicroscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 80, 928–938.

- Tsai, T.H.; Leggett, C.L.; Trindade, A.J.; Sethi, A.; Swager, A.F.; Joshi, V.; Bergman, J.J.; Mashimo, H.; Nishioka, N.S.; Namati, E. Optical coherence tomography in gastroenterology: A review and future outlook. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 1–17.

- Takada, K.; Yokohama, I.; Chida, K.; Noda, J. New measurement system for fault location in optical waveguide devices based on an interferometric technique. Appl. Opt. 1987, 26, 1603–1606.

- Gilgen, H.H.; Novak, R.P.; Salathe, R.P.; Hodel, W.; Beaud, P. Submillimeter optical reflectometry. J. Lightw. Technol. 1989, 7, 1225–1233.

- Huang, D.; Swanson, E.A.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Stinson, W.G.; Chang, W.; Hee, M.R.; Flotte, T.; Gregory, K.; Puliafito, C.A.; et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science 1991, 254, 1178–1181.

- Tearney, G.J.; Brezinski, M.E.; Bouma, B.E.; Boppart, S.A.; Pitris, C.; Southern, J.F.; Fujimoto, J.G. In vivo endoscopic optical biopsy with optical coherence tomography. Science 1997, 276, 2037–2039.

- Swanson, E.A.; Izatt, J.A.; Hee, M.R.; Huang, D.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Puliafito, C.A.; Fujimoto, J.G. In vivo retinal imaging by optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 1993, 18, 1864–1866.

- Fercher, A.F.; Hitzenberger, C.K.; Kamp, G.; El-Zaiat, S.Y. Measurement of intraocular distances by backscattering spectral interferometry. Opt. Commun. 1995, 117, 43–48.

- Cense, B.; Nassif, N.A.; Chen, T.C.; Pierce, M.C.; Yun, S.-H.; Park, B.H.; Bouma, B.E.; Tearney, G.J.; de Boer, J.F. Ultrahigh-resolution high-speed retinal imaging using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 2435–2447.

- Wojtkowski, M.; Bajraszewski, T.; Gorczyńska, I.; Targowski, P.; Kowalczyk, A.; Wasilewski, W.; Radzewicz, C. Ophthalmic imaging by spectral optical coherence tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2004, 138, 412–419.

- Popescu, D.P.; Choo-Smith, L.-P.I.; Flueraru, C.; Mao, Y.; Chang, S.; Disano, J.; Sherif, S.; Sowa, M.G. Optical coherence tomography: Fundamental principles, instrumental designs and biomedical applications. Biophys. Rev. 2011, 3, 155.

- Swanson, E.A.; Huang, D.; Hee, M.R.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Lin, C.P.; Puliafito, C.A. High-speed optical coherence domain reflectometry. Opt. Lett. 1992, 17, 151–153.

- Tsai, T.-H.; Fujimoto, G.J.; Mashimo, H. Endoscopic Optical Coherence Tomography for Clinical Gastroenterology. Diagnostics 2014, 4, 57–93.

- Choma, M.; Sarunic, M.; Yang, C.; Izatt, J. Sensitivity advantage of swept source and Fourier domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2003, 11, 2183–2189.

- de Boer, J.F.; Cense, B.; Park, B.H.; Pierce, M.C.; Tearney, G.J.; Bouma, B.E. Improved signal-to-noise ratio in spectral-domain compared with time-domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 2003, 28, 2067–2069.

- Leitgeb, R.; Hitzenberger, C.K.; Fercher, A.F. Performance of fourier domain vs. time domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2003, 11, 889–894.

- Ko, T.H.; Adler, D.C.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Mamedov, D.; Prokhorov, V.; Shidlovski, V.; Yakubovich, S. Ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography imaging with a broadband superluminescent diode light source. Opt. Express 2004, 12, 2112–2119.

- Robles, F.E.; Chowdhury, S.; Wax, A. Assessing hemoglobin concentration using spectroscopic optical coherence tomography for feasibility of tissue diagnostics. Biomed. Opt. Express 2010, 1, 310–317.

- Tsai, T.H.; Potsaid, B.; Kraus, M.F.; Zhou, C.; Tao, Y.K.; Hornegger, J.; Fujimoto, J.G. Piezoelectric-transducer-based miniature catheter for ultrahigh-speed endoscopic optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2011, 2, 2438–2448.

- Wieser, W.; Biedermann, B.R.; Klein, T.; Eigenwillig, C.M.; Huber, R. Multi-Megahertz OCT: High quality 3D imaging at 20 million A-scans and 4.5 GVoxels per second. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 14685–14704.

- Wang, T.; Pfeiffer, T.; Regar, E.; Wieser, W.; van Beusekom, H.; Lancee, C.T.; Springeling, G.; Krabbendam-Peters, I.; van der Steen, A.F.W.; Huber, R.; et al. Heartbeat OCT and Motion-Free 3D In Vivo Coronary Artery Microscopy. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, 622–623.

- Vakoc, B.J.; Shishko, M.; Yun, S.H.; Oh, W.Y.; Suter, M.J.; Desjardins, A.E.; Evans, J.A.; Nishioka, N.S.; Tearney, G.J.; Bouma, B.E. Comprehensive esophageal microscopy by using optical frequency-domain imaging (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2007, 65, 898–905.

- Adler, D.C.; Chen, Y.; Huber, R.; Schmitt, J.; Connolly, J.; Fujimoto, J.G. Three-dimensional endomicroscopy using optical coherence tomography. Nat. Photonics 2007, 1, 709.

- Steele, D.; Baig, K.K.K.; Peter, S. Evolving screening and surveillance techniques for Barrett’s esophagus. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2045–2057.

- Maes, S.; Sharma, P.; Bisschops, R. Review: Surveillance of patients with Barrett oesophagus. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 901–912.

- Hur, C.; Miller, M.; Kong, C.Y.; Dowling, E.C.; Nattinger, K.J.; Dunn, M.; Feuer, E.J. Trends in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality. Cancer 2013, 119, 1149–1158.

- Lagergren, J.; Lagergren, P. Recent developments in esophageal adenocarcinoma. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 63, 232–248.

- Souza, R.F.; Morales, C.P.; Spechler, S.J. Review article: A conceptual approach to understanding the molecular mechanisms of cancer development in Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 1087–1100.

- Weston, A.P.; Banerjee, S.K.; Sharma, P.; Tran, T.M.; Richards, R.; Cherian, R. p53 protein overexpression in low grade dysplasia (LGD) in Barrett’s esophagus: Immunohistochemical marker predictive of progression. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 96, 1355–1362.

- Shaheen, N.J.; Falk, G.W.; Iyer, P.G.; Gerson, L.B. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 30.

- Zhou, C.; Tsai, T.H.; Lee, H.C.; Kirtane, T.; Figueiredo, M.; Tao, Y.K.; Ahsen, O.O.; Adler, D.C.; Schmitt, J.M.; Huang, Q.; et al. Characterization of buried glands before and after radiofrequency ablation by using 3-dimensional optical coherence tomography (with videos). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 76, 32–40.

- Pouw, R.E.; Gondrie, J.J.; Rygiel, A.M.; Sondermeijer, C.M.; ten Kate, F.J.; Odze, R.D.; Vieth, M.; Krishnadath, K.K.; Bergman, J.J. Properties of the neosquamous epithelium after radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus containing neoplasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 1366–1373.

- Mashimo, H. Subsquamous intestinal metaplasia after ablation of Barrett’s esophagus: Frequency and importance. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 29, 454–459.

- Sharma, P.; Savides, T.J.; Canto, M.I.; Corley, D.A.; Falk, G.W.; Goldblum, J.R.; Wang, K.K.; Wallace, M.B.; Wolfsen, H.C. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on imaging in Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 76, 252–254.

- Evans, J.A.; Poneros, J.M.; Bouma, B.E.; Bressner, J.; Halpern, E.F.; Shishkov, M.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Nishioka, N.S.; Tearney, G.J. Optical coherence tomography to identify intramucosal carcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 4, 38–43.

- Suter, M.J.; Vakoc, B.J.; Yachimski, P.S.; Shishkov, M.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Bouma, B.E.; Nishioka, N.S.; Tearney, G.J. Comprehensive microscopy of the esophagus in human patients with optical frequency domain imaging. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008, 68, 745–753.

- Trindade, A.J.; Vamadevan, A.S.; Sejpal, D.V. Finding a needle in a haystack: Use of volumetric laser endomicroscopy in targeting focal dysplasia in long-segment Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 82, 756–757.

- Leggett, C.L.; Gorospe, E.C.; Chan, D.K.; Muppa, P.; Owens, V.; Smyrk, T.C.; Anderson, M.; Lutzke, L.S.; Tearney, G.; Wang, K.K. Comparative diagnostic performance of volumetric laser endomicroscopy and confocal laser endomicroscopy in the detection of dysplasia associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 83, 880–888.

- Swager, A.F.; Tearney, G.J.; Leggett, C.L.; van Oijen, M.G.H.; Meijer, S.L.; Weusten, B.L.; Curvers, W.L.; Bergman, J. Identification of volumetric laser endomicroscopy features predictive for early neoplasia in Barrett’s esophagus using high-quality histological correlation. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 85, 918–926.

- Suter, M.J.; Jillella, P.A.; Vakoc, B.J.; Halpern, E.F.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Bouma, B.E.; Nishioka, N.S.; Tearney, G.J. Image-guided biopsy in the esophagus through comprehensive optical frequency domain imaging and laser marking: A study in living swine. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 71, 346–353.

- Ahsen, O.O.; Lee, H.C.; Liang, K.; Wang, Z.; Figueiredo, M.; Huang, Q.; Potsaid, B.; Jayaraman, V.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Mashimo, H. Ultrahigh-speed endoscopic optical coherence tomography and angiography enables delineation of lateral margins of endoscopic mucosal resection: A case report. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 931–936.

- Colorectal Cancer Facts and Figures 2017–2019. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2019.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Wolf, A.M.D.; Fontham, E.T.H.; Church, T.R.; Flowers, C.R.; Guerra, C.E.; LaMonte, S.J.; Etzioni, R.; McKenna, M.T.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Shih, Y.-C.T.; et al. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 250–281.

- Kim, N.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Jeong, W.S.; Yang, H.-J.; Park, S.-K.; Choi, K.; Park, D.I. Miss rate of colorectal neoplastic polyps and risk factors for missed polyps in consecutive colonoscopies. Intest. Res. 2017, 15, 411–418.

- Pfau, P.R.; Sivak, M.V., Jr.; Chak, A.; Kinnard, M.; Wong, R.C.; Isenberg, G.A.; Izatt, J.A.; Rollins, A.; Westphal, V. Criteria for the diagnosis of dysplasia by endoscopic optical coherence tomography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003, 58, 196–202.

- Zagaynova, E.; Gladkova, N.; Shakhova, N.; Gelikonov, G.; Gelikonov, V. Endoscopic OCT with forward-looking probe: Clinical studies in urology and gastroenterology. J. Biophotonics 2008, 1, 114–128.

- Trindade, A.J.; Sultan, K.; Vamadevan, A.S.; Fan, C.; Sejpal, D.V. Successful use of volumetric laser endomicroscopy in imaging a rectal polyp. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2015, 9, 128–131.

- Liang, K.; Ahsen, O.O.; Wang, Z.; Lee, H.-C.; Liang, W.; Potsaid, B.M.; Tsai, T.-H.; Giacomelli, M.G.; Jayaraman, V.; Mashimo, H.; et al. Endoscopic forward-viewing optical coherence tomography and angiography with MHz swept source. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 3193–3196.

- Blechacz, B. Cholangiocarcinoma: Current Knowledge and New Developments. Gut Liver 2017, 11, 13–26.

- Pugliese, V.; Pujic, N.; Saccomanno, S.; Gatteschi, B.; Pera, C.; Aste, H.; Ferrara, G.B.; Nicolò, G. Pancreatic intraductal sampling during ERCP in patients with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: Cytologic studies and k-ras-2 codon 12 molecular analysis in 47 cases. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001, 54, 595–599.

- Rösch, T.; Hofrichter, K.; Frimberger, E.; Meining, A.; Born, P.; Weigert, N.; Allescher, H.-D.; Classen, M.; Barbur, M.; Schenck, U.; et al. ERCP or EUS for tissue diagnosis of biliary strictures? A prospective comparative study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2004, 60, 390–396.

- Selvaggi, S.M. Biliary brushing cytology. Cytopathology 2004, 15, 74–79.

- de Bellis, M.; Sherman, S.; Fogel, E.L.; Cramer, H.; Chappo, J.; McHenry, L.; Watkins, J.L.; Lehman, G.A. Tissue sampling at ERCP in suspected malignant biliary strictures (Part 2). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2002, 56, 720–730.

- Seitz, U.; Freund, J.; Jaeckle, S.; Feldchtein, F.; Bohnacker, S.; Thonke, F.; Gladkova, N.; Brand, B.; Schroder, S.; Soehendra, N. First in vivo optical coherence tomography in the human bile duct. Endoscopy 2001, 33, 1018–1021.

- Poneros, J.M.; Tearney, G.J.; Shiskov, M.; Kelsey, P.B.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Nishioka, N.S.; Bouma, B.E. Optical coherence tomography of the biliary tree during ERCP. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2002, 55, 84–88.

- Testoni, P.A.; Mariani, A.; Mangiavillano, B.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Di Pietro, S.; Masci, E. Intraductal optical coherence tomography for investigating main pancreatic duct strictures. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 269–274.

- Tyberg, A.; Xu, M.-M.; Gaidhane, M.; Sharaiha, R.Z.; Kahaleh, M. Tu2004—Second Generation Optical Coherence Tomography: Preliminary Experience in Pancreatic and Biliary Strictures. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, S1032–S1033.

- Joshi, V.; Patel, S.N.; Vanderveldt, H.; Oliva, I.; Raijman, I.; Molina, C.; Carr-Locke, D.L. Mo1963 A Pilot Study of Safety and Efficacy of Directed Cannulation with a Low Profile Catheter (LP) and Imaging Characteristics of Bile Duct Wall Using Optical Coherance Tomography (OCT) for Indeterminate Biliary Strictures Initial Report on In-Vivo Evaluation During ERCP. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 85, AB496–AB497.

- Tsai, T.-H.; Ahsen, O.O.; Lee, H.-C.; Liang, K.; Figueiredo, M.; Tao, Y.K.; Giacomelli, M.G.; Potsaid, B.M.; Jayaraman, V.; Huang, Q. Endoscopic optical coherence angiography enables 3-dimensional visualization of subsurface microvasculature. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1219–1221.

- Supplementary Material. Available online: https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(14)01073-7/fulltext#appsec1 (accessed on 19 July 2019).

- Lee, M.M.; Enns, R. Narrow band imaging in gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 23, 84–87.

- Singh, R.; Anagnostopoulos, G.K.; Yao, K.; Karageorgiou, H.; Fortun, P.J.; Shonde, A.; Garsed, K.; Kaye, P.V.; Hawkey, C.J.; Ragunath, K. Narrow-band imaging with magnification in Barrett’s esophagus: Validation of a simplified grading system of mucosal morphology patterns against histology. Endoscopy 2008, 40, 457–463.

- Zhou, C.; Adler, D.C.; Becker, L.; Chen, Y.; Tsai, T.-H.; Figueiredo, M.; Schmitt, J.M.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Mashimo, H. Effective treatment of chronic radiation proctitis using radiofrequency ablation. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2009, 2, 149–156.

- Lenz, L.; Rohr, R.; Nakao, F.; Libera, E.; Ferrari, A. Chronic radiation proctopathy: A practical review of endoscopic treatment. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 151–160.

- Nojkov, B.; Cappell, M.S. Gastrointestinal bleeding from Dieulafoy’s lesion: Clinical presentation, endoscopic findings, and endoscopic therapy. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 7, 295–307.

- Lee, H.-C.; Ahsen, O.O.; Liang, K.; Wang, Z.; Figueiredo, M.; Potsaid, B.; Jayaraman, V.; Huang, Q.; Mashimo, H.; Fujimoto, J.G. Sa2034 Novel Ultrahigh Speed Endoscopic OCT Angiography Identifies Both Architectural and Microvascular Changes in Patients with Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia (GAVE) Undergoing Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) Treatment. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, S435–S436.

- Masci, E.; Mangiavillano, B.; Albarello, L.; Mariani, A.; Doglioni, C.; Testoni, P.A. Pilot study on the correlation of optical coherence tomography with histology in celiac disease and normal subjects. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, 2256–2260.

- Masci, E.; Mangiavillano, B.; Barera, G.; Parma, B.; Albarello, L.; Mariani, A.; Doglioni, C.; Testoni, P.A. Optical coherence tomography in pediatric patients: A feasible technique for diagnosing celiac disease in children with villous atrophy. Dig. Liver Dis. 2009, 41, 639–643.

- Kamboj, A.K.; Chan, D.K.; Zakko, L.; Visrodia, K.; Otaki, F.; Lutzke, L.S.; Wang, K.K.; Leggett, C.L. Mo2006 Detection of Barrett’s Esophagus Dysplasia Using a Novel Volumetric Laser Endomicroscopy Computer Algorithm. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 85, AB518.

- Lee, H.-C.; Ahsen, O.O.; Liang, K.; Wang, Z.; Figueiredo, M.; Giacomelli, M.G.; Potsaid, B.; Huang, Q.; Mashimo, H.; Fujimoto, J.G. Endoscopic optical coherence tomography angiography microvascular features associated with dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 86, 476–484.