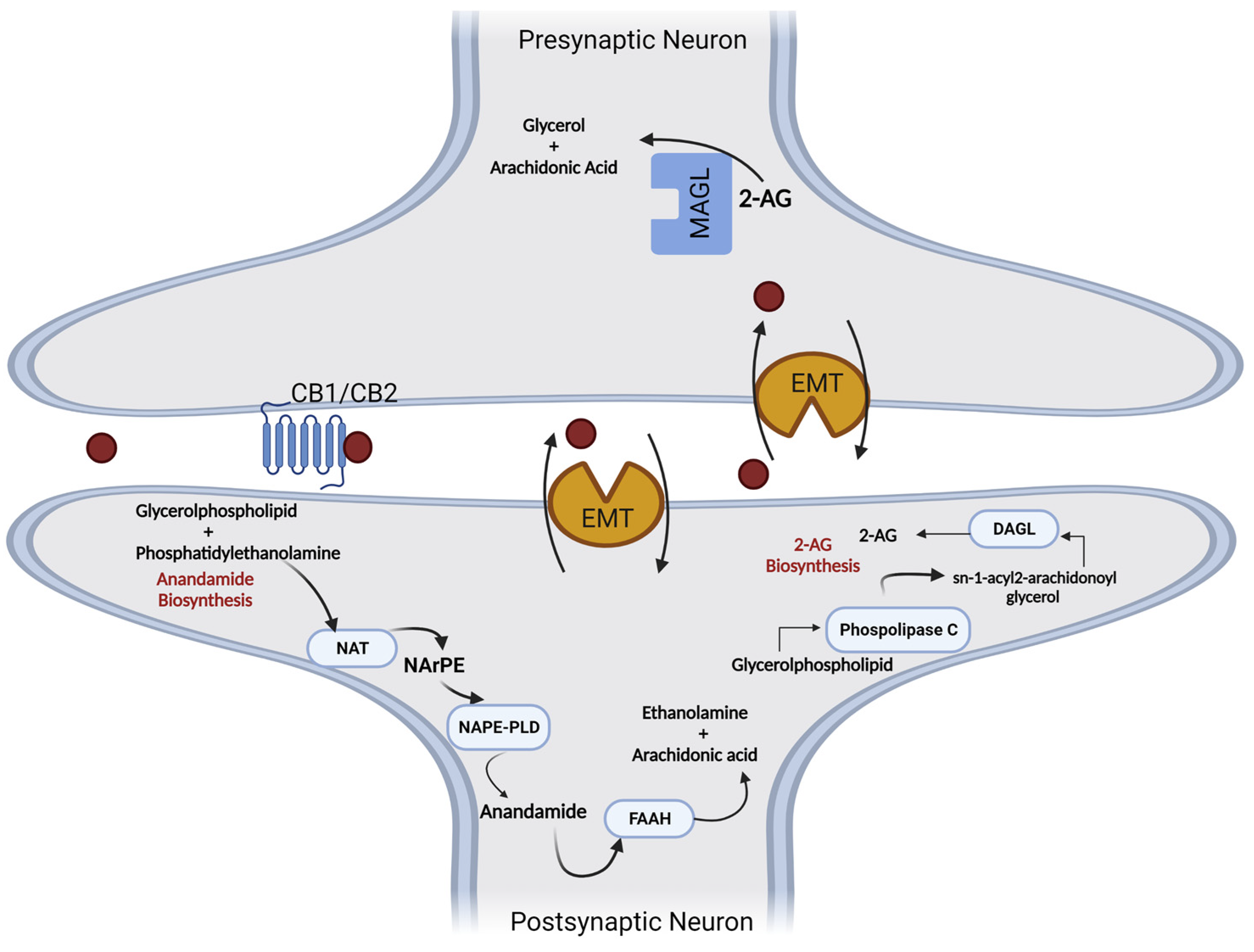

The endocannabinoid system (eCB) has been studied to identify the molecular structures present in Cannabis sativa. eCB consists of cannabinoid receptors, endogenous ligands, and the associated enzymatic apparatus responsible for maintaining energy homeostasis and cognitive processes. Several physiological effects of cannabinoids are exerted through interactions with various receptors, such as CB1 and CB2 receptors, vanilloid receptors, and the recently discovered G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR55, GPR3, GPR6, GPR12, and GPR19). Anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidoylglycerol (2-AG), two small lipids derived from arachidonic acid, showed high-affinity binding to both CB1 and CB2 receptors.

- endocannabinoid system

- receptor cannabinoid

- endocannabinoid ligands

- cannabis

1. Endocannabinoids: Synthesis, Release, and Metabolism

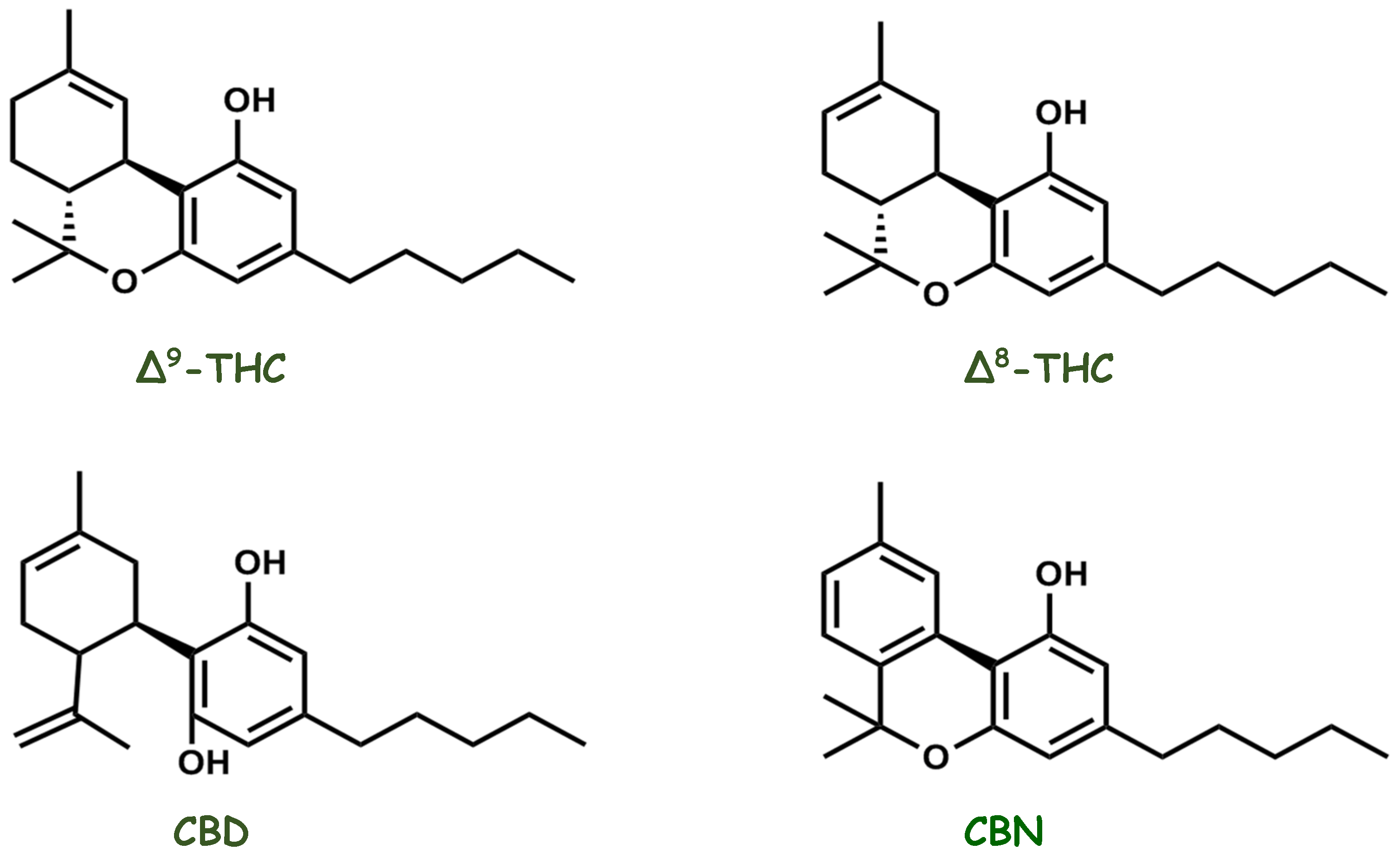

2. Molecules That Modulate the Endocannabinoid System

3. Endocannabinoid System Emerging as a Pharmacotherapy Target for Chronic Pain and Mood Disorders

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ph16020148

References

- Devane, W.A.; Hanus, L.; Breuer, A.; Pertwee, R.G.; Stevenson, L.A.; Griffin, G.; Gibson, D.; Mandelbaum, A.; Etinger, A.; Mechoulam, R. Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 1992, 258, 1946–1949.

- Kano, M.; Ohno-Shosaku, T.; Hashimotodani, Y.; Uchigashima, M.; Watanabe, M. Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 309–380.

- Mackie, K.; Devane, W.A.; Hille, B. Anandamide, an endogenous cannabinoid, inhibits calcium currents as a partial agonist in N18 neuroblastoma cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993, 44, 498–503.

- Martin, B.R.; Mechoulam, R.; Razdan, R.K. Discovery and characterization of endogenous cannabinoids. Life Sci. 1999, 65, 573–595.

- Goutopoulos, A.; Makriyannis, A. From cannabis to cannabinergics: New therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 95, 103–117.

- Ueda, N.; Tsuboi, K.; Uyama, T. Enzymological studies on the biosynthesis of N-acylethanolamines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 1274–1285.

- Di Marzo, V.; Bifulco, M.; De Petrocellis, L. The endocannabinoid system and its therapeutic exploitation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 771–784.

- Petrosino, S.; Ligresti, A.; Di Marzo, V. Endocannabinoid chemical biology: A tool for the development of novel therapies. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009, 13, 309–320.

- Kilaru, A.; Chapman, K.D. The endocannabinoid system. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 485–499.

- Mechoulam, R.; Ben-Shabat, S.; Hanus, L.; Ligumsky, M.; Kaminski, N.E.; Schatz, A.R.; Gopher, A.; Almog, S.; Martin, B.R.; Compton, D.R.; et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995, 50, 83–90.

- Sugiura, T.; Kondo, S.; Sukagawa, A.; Nakane, S.; Shinoda, A.; Itoh, K.; Yamashita, A.; Waku, K. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: A possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 215, 89–97.

- Rodriguez de Fonseca, F.; Navarro, M.; Gomez, R.; Escuredo, L.; Nava, F.; Fu, J.; Murillo-Rodriguez, E.; Giuffrida, A.; LoVerme, J.; Gaetani, S.; et al. An anorexic lipid mediator regulated by feeding. Nature 2001, 414, 209–212.

- Hanus, L.; Abu-Lafi, S.; Fride, E.; Breuer, A.; Vogel, Z.; Shalev, D.E.; Kustanovich, I.; Mechoulam, R. 2-arachidonyl glyceryl ether, an endogenous agonist of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3662–3665.

- Porter, A.C.; Sauer, J.M.; Knierman, M.D.; Becker, G.W.; Berna, M.J.; Bao, J.; Nomikos, G.G.; Carter, P.; Bymaster, F.P.; Leese, A.B.; et al. Characterization of a novel endocannabinoid, virodhamine, with antagonist activity at the CB1 receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 301, 1020–1024.

- Huang, S.M.; Bisogno, T.; Trevisani, M.; Al-Hayani, A.; De Petrocellis, L.; Fezza, F.; Tognetto, M.; Petros, T.J.; Krey, J.F.; Chu, C.J.; et al. An endogenous capsaicin-like substance with high potency at recombinant and native vanilloid VR1 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 8400–8405.

- Bisogno, T.; Maurelli, S.; Melck, D.; De Petrocellis, L.; Di Marzo, V. Biosynthesis, uptake, and degradation of anandamide and palmitoylethanolamide in leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 3315–3323.

- Lu, H.C.; Mackie, K. An Introduction to the Endogenous Cannabinoid System. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 79, 516–525.

- Piette, C.; Cui, Y.; Gervasi, N.; Venance, L. Lights on Endocannabinoid-Mediated Synaptic Potentiation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 132.

- Maccarrone, M.; Bab, I.; Biro, T.; Cabral, G.A.; Dey, S.K.; Di Marzo, V.; Konje, J.C.; Kunos, G.; Mechoulam, R.; Pacher, P.; et al. Endocannabinoid signaling at the periphery: 50 years after THC. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 36, 277–296.

- Chapman, K.D. Emerging physiological roles for N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in plants: Signal transduction and membrane protection. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2000, 108, 221–229.

- Ueda, N.; Okamoto, Y.; Tsuboi, K. Endocannabinoid-related enzymes as drug targets with special reference to N-acylphosphatidylethanolamine-hydrolyzing phospholipase D. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 1413–1422.

- Ueda, N.; Tsuboi, K.; Uyama, T.; Ohnishi, T. Biosynthesis and degradation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Biofactors 2011, 37, 1–7.

- Zhu, D.; Gao, F.; Chen, C. Endocannabinoid Metabolism and Traumatic Brain Injury. Cells 2021, 10, 2979.

- Ueda, N. Endocannabinoid hydrolases. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002, 68–69, 521–534.

- Basavarajappa, B.S.; Shivakumar, M.; Joshi, V.; Subbanna, S. Endocannabinoid system in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurochem 2017, 142, 624–648.

- Russo, E.B. Clinical endocannabinoid deficiency (CECD): Can this concept explain therapeutic benefits of cannabis in migraine, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and other treatment-resistant conditions? Neuro. Endocrinol. Lett. 2004, 25, 31–39.

- Hill, M.N.; Gorzalka, B.B. Is there a role for the endocannabinoid system in the etiology and treatment of melancholic depression? Behav. Pharmacol. 2005, 16, 333–352.

- Schlabritz-Loutsevitch, N.; German, N.; Ventolini, G.; Larumbe, E.; Samson, J. Fetal Syndrome of Endocannabinoid Deficiency (FSECD) In Maternal Obesity. Med. Hypotheses 2016, 96, 35–38.

- Boger, D.L.; Patterson, J.E.; Jin, Q. Structural requirements for 5-HT2A and 5-HT1A serotonin receptor potentiation by the biologically active lipid oleamide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 4102–4107.

- Russo, E.B. Clinical Endocannabinoid Deficiency Reconsidered: Current Research Supports the Theory in Migraine, Fibromyalgia, Irritable Bowel, and Other Treatment-Resistant Syndromes. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 154–165.

- Walitt, B.; Klose, P.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Phillips, T.; Hauser, W. Cannabinoids for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, CD011694.

- Khurshid, H.; Qureshi, I.A.; Jahan, N.; Went, T.R.; Sultan, W.; Sapkota, A.; Alfonso, M. A Systematic Review of Fibromyalgia and Recent Advancements in Treatment: Is Medicinal Cannabis a New Hope? Cureus 2021, 13, e17332.

- Brierley, S.M.; Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B.; Sarnelli, G.; Sharkey, K.A.; Storr, M.; Tack, J. Targeting the endocannabinoid system for the treatment of abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 5–25.

- Fraguas-Sanchez, A.I.; Torres-Suarez, A.I. Medical Use of Cannabinoids. Drugs 2018, 78, 1665–1703.

- Nasser, Y.; Woo, M.; Andrews, C.N. Cannabis in Gastroenterology: Watch Your Head! A Review of Use in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Functional Gut Disorders, and Gut-Related Adverse Effects. Curr. Treat. Opt. Gastroenterol. 2020, 18, 519–530.

- Di Carlo, G.; Izzo, A.A. Cannabinoids for gastrointestinal diseases: Potential therapeutic applications. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2003, 12, 39–49.

- Akbar, A.; Yiangou, Y.; Facer, P.; Walters, J.R.; Anand, P.; Ghosh, S. Increased capsaicin receptor TRPV1-expressing sensory fibres in irritable bowel syndrome and their correlation with abdominal pain. Gut 2008, 57, 923–929.

- Bisogno, T.; Hanus, L.; De Petrocellis, L.; Tchilibon, S.; Ponde, D.E.; Brandi, I.; Moriello, A.S.; Davis, J.B.; Mechoulam, R.; Di Marzo, V. Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: Effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 134, 845–852.

- Leweke, F.M.; Piomelli, D.; Pahlisch, F.; Muhl, D.; Gerth, C.W.; Hoyer, C.; Klosterkotter, J.; Hellmich, M.; Koethe, D. Cannabidiol enhances anandamide signaling and alleviates psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e94.

- Pisani, A.; Fezza, F.; Galati, S.; Battista, N.; Napolitano, S.; Finazzi-Agro, A.; Bernardi, G.; Brusa, L.; Pierantozzi, M.; Stanzione, P.; et al. High endogenous cannabinoid levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of untreated Parkinson’s disease patients. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 777–779.

- Cooray, R.; Gupta, V.; Suphioglu, C. Current Aspects of the Endocannabinoid System and Targeted THC and CBD Phytocannabinoids as Potential Therapeutics for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases: A Review. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 4878–4890.

- Berry, A.J.; Zubko, O.; Reeves, S.J.; Howard, R.J. Endocannabinoid system alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of human studies. Brain Res. 2020, 1749, 147135.

- Busquets-Garcia, A.; Gomis-Gonzalez, M.; Guegan, T.; Agustin-Pavon, C.; Pastor, A.; Mato, S.; Perez-Samartin, A.; Matute, C.; de la Torre, R.; Dierssen, M.; et al. Targeting the endocannabinoid system in the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 603–607.

- Navarro-Romero, A.; Vazquez-Oliver, A.; Gomis-Gonzalez, M.; Garzon-Montesinos, C.; Falcon-Moya, R.; Pastor, A.; Martin-Garcia, E.; Pizarro, N.; Busquets-Garcia, A.; Revest, J.M.; et al. Cannabinoid type-1 receptor blockade restores neurological phenotypes in two models for Down syndrome. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 125, 92–106.

- Navarro-Romero, A.; Galera-Lopez, L.; Ortiz-Romero, P.; Llorente-Ovejero, A.; de Los Reyes-Ramirez, L.; Bengoetxea de Tena, I.; Garcia-Elias, A.; Mas-Stachurska, A.; Reixachs-Sole, M.; Pastor, A.; et al. Cannabinoid signaling modulation through JZL184 restores key phenotypes of a mouse model for Williams-Beuren syndrome. Elife 2022, 11, e72560.

- Radwan, M.M.; Chandra, S.; Gul, S.; ElSohly, M.A. Cannabinoids, Phenolics, Terpenes and Alkaloids of Cannabis. Molecules 2021, 26.

- Sommano, S.R.; Chittasupho, C.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Jantrawut, P. The Cannabis Terpenes. Molecules 2020, 25, 5792.

- Mechoulam, R.; Gaoni, Y. A Total Synthesis of Dl-Delta-1-Tetrahydrocannabinol, the Active Constituent of Hashish. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 3273–3275.

- Odieka, A.E.; Obuzor, G.U.; Oyedeji, O.O.; Gondwe, M.; Hosu, Y.S.; Oyedeji, A.O. The Medicinal Natural Products of Cannabis sativa Linn.: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 1689.

- Goncalves, E.C.D.; Baldasso, G.M.; Bicca, M.A.; Paes, R.S.; Capasso, R.; Dutra, R.C. Terpenoids, Cannabimimetic Ligands, beyond the Cannabis Plant. Molecules 2020, 25, 1567.

- Atakan, Z. Cannabis, a complex plant: Different compounds and different effects on individuals. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 2, 241–254.

- Procaccia, S.; Lewitus, G.M.; Lipson Feder, C.; Shapira, A.; Berman, P.; Meiri, D. Cannabis for Medical Use: Versatile Plant Rather Than a Single Drug. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 894960.

- Huestis, M.A.; Solimini, R.; Pichini, S.; Pacifici, R.; Carlier, J.; Busardo, F.P. Cannabidiol Adverse Effects and Toxicity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 974–989.

- Britch, S.C.; Babalonis, S.; Walsh, S.L. Cannabidiol: Pharmacology and therapeutic targets. Psychopharmacology 2021, 238, 9–28.

- Iversen, L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain 2003, 126, 1252–1270.

- Soethoudt, M.; Hoorens, M.W.H.; Doelman, W.; Martella, A.; van der Stelt, M.; Heitman, L.H. Structure-kinetic relationship studies of cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonists reveal substituent-specific lipophilic effects on residence time. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 152, 129–142.

- Castaneto, M.S.; Wohlfarth, A.; Desrosiers, N.A.; Hartman, R.L.; Gorelick, D.A.; Huestis, M.A. Synthetic cannabinoids pharmacokinetics and detection methods in biological matrices. Drug Metab. Rev. 2015, 47, 124–174.

- Sharma, M.K.; Murumkar, P.R.; Kanhed, A.M.; Giridhar, R.; Yadav, M.R. Prospective therapeutic agents for obesity: Molecular modification approaches of centrally and peripherally acting selective cannabinoid 1 receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 79, 298–339.

- Worm, K.; Dolle, R.E. Simultaneous optimization of potency, selectivity and physicochemical properties for cannabinoid CB(2) ligands. Curr. Pharmacol. Des. 2009, 15, 3345–3366.

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019, 160, 19–27.

- Goldberg, D.S.; McGee, S.J. Pain as a global public health priority. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 770.

- Dydyk, A.M.; Conermann, T. Chronic Pain. In StatPearls; Treasure Island, FL, USA, StatPearls Publishing, 2022.

- Aronoff, G.M. What Do We Know About the Pathophysiology of Chronic Pain? Implications for Treatment Considerations. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 100, 31–42.

- Legare, C.A.; Raup-Konsavage, W.M.; Vrana, K.E. Therapeutic Potential of Cannabis, Cannabidiol, and Cannabinoid-Based Pharmaceuticals. Pharmacology 2022, 107, 131–149.

- Petzke, F.; Tolle, T.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Hauser, W. Cannabis-Based Medicines and Medical Cannabis for Chronic Neuropathic Pain. CNS Drugs 2022, 36, 31–44.

- Sofia, R.D.; Nalepa, S.D.; Harakal, J.J.; Vassar, H.B. Anti-edema and analgesic properties of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1973, 186, 646–655.

- Formukong, E.A.; Evans, A.T.; Evans, F.J. Analgesic and antiinflammatory activity of constituents of Cannabis sativa L. Inflammation 1988, 12, 361–371.

- Calignano, A.; La Rana, G.; Giuffrida, A.; Piomelli, D. Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature 1998, 394, 277–281.

- Ulugol, A.; Ozyigit, F.; Yesilyurt, O.; Dogrul, A. The additive antinociceptive interaction between WIN 55,212-2, a cannabinoid agonist, and ketorolac. Anesth Analg. 2006, 102, 443–447.

- Costa, B.; Colleoni, M.; Conti, S.; Parolaro, D.; Franke, C.; Trovato, A.E.; Giagnoni, G. Oral anti-inflammatory activity of cannabidiol, a non-psychoactive constituent of cannabis, in acute carrageenan-induced inflammation in the rat paw. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 2004, 369, 294–299.

- Martin, W.J.; Hohmann, A.G.; Walker, J.M. Suppression of noxious stimulus-evoked activity in the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus by a cannabinoid agonist: Correlation between electrophysiological and antinociceptive effects. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 6601–6611.

- Guindon, J.; Beaulieu, P. Antihyperalgesic effects of local injections of anandamide, ibuprofen, rofecoxib and their combinations in a model of neuropathic pain. Neuropharmacology 2006, 50, 814–823.

- de Paula Rodrigues, B.M.; Coimbra, N.C. CB(1) receptor signalling mediates cannabidiol-induced panicolytic-like effects and defensive antinociception impairment in mice threatened by Bothrops jararaca lancehead pit vipers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 1384–1396.

- Herzberg, U.; Eliav, E.; Bennett, G.J.; Kopin, I.J. The analgesic effects of R(+)-WIN 55,212-2 mesylate, a high affinity cannabinoid agonist, in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 221, 157–160.

- Bridges, D.; Ahmad, K.; Rice, A.S. The synthetic cannabinoid WIN55,212-2 attenuates hyperalgesia and allodynia in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 133, 586–594.

- Fox, A.; Kesingland, A.; Gentry, C.; McNair, K.; Patel, S.; Urban, L.; James, I. The role of central and peripheral Cannabinoid1 receptors in the antihyperalgesic activity of cannabinoids in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain 2001, 92, 91–100.

- Casey, S.L.; Mitchell, V.A.; Sokolaj, E.E.; Winters, B.L.; Vaughan, C.W. Intrathecal Actions of the Cannabis Constituents Delta(9)-Tetrahydrocannabinol and Cannabidiol in a Mouse Neuropathic Pain Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8649.

- Guindon, J.; De Lean, A.; Beaulieu, P. Local interactions between anandamide, an endocannabinoid, and ibuprofen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, in acute and inflammatory pain. Pain 2006, 121, 85–93.

- Klinger-Gratz, P.P.; Ralvenius, W.T.; Neumann, E.; Kato, A.; Nyilas, R.; Lele, Z.; Katona, I.; Zeilhofer, H.U. Acetaminophen Relieves Inflammatory Pain through CB1 Cannabinoid Receptors in the Rostral Ventromedial Medulla. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 322–334.

- Ottani, A.; Leone, S.; Sandrini, M.; Ferrari, A.; Bertolini, A. The analgesic activity of paracetamol is prevented by the blockade of cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 531, 280–281.

- Dani, M.; Guindon, J.; Lambert, C.; Beaulieu, P. The local antinociceptive effects of paracetamol in neuropathic pain are mediated by cannabinoid receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 573, 214–215.

- Schultz, S.; Gould, G.G.; Antonucci, N.; Brigida, A.L.; Siniscalco, D. Endocannabinoid System Dysregulation from Acetaminophen Use May Lead to Autism Spectrum Disorder: Could Cannabinoid Treatment Be Efficacious? Molecules 2021, 26, 1845.

- Mucke, M.; Phillips, T.; Radbruch, L.; Petzke, F.; Hauser, W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 3, CD012182.

- Toth, C.; Mawani, S.; Brady, S.; Chan, C.; Liu, C.; Mehina, E.; Garven, A.; Bestard, J.; Korngut, L. An enriched-enrolment, randomized withdrawal, flexible-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel assignment efficacy study of nabilone as adjuvant in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 2012, 153, 2073–2082.

- Schimrigk, S.; Marziniak, M.; Neubauer, C.; Kugler, E.M.; Werner, G.; Abramov-Sommariva, D. Dronabinol Is a Safe Long-Term Treatment Option for Neuropathic Pain Patients. Eur. Neurol. 2017, 78, 320–329.

- Weber, J.; Schley, M.; Casutt, M.; Gerber, H.; Schuepfer, G.; Rukwied, R.; Schleinzer, W.; Ueberall, M.; Konrad, C. Tetrahydrocannabinol (Delta 9-THC) Treatment in Chronic Central Neuropathic Pain and Fibromyalgia Patients: Results of a Multicenter Survey. Anesth. Res. Pr. 2009, 2009, 827290.

- Huang, W.J.; Chen, W.W.; Zhang, X. Endocannabinoid system: Role in depression, reward and pain control (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 2899–2903.

- Vimal, D.; D’Souza, L.C.; Rai, V.; Lal, S.; Sharma, A.; Gupta, S.C. Efficacy of cannabis and its constituents in disease management: Insights from clinical studies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 30, 178–202.

- Ware, M.A.; Wang, T.; Shapiro, S.; Robinson, A.; Ducruet, T.; Huynh, T.; Gamsa, A.; Bennett, G.J.; Collet, J.P. Smoked cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2010, 182, E694–E701.

- Abrams, D.I.; Jay, C.A.; Shade, S.B.; Vizoso, H.; Reda, H.; Press, S.; Kelly, M.E.; Rowbotham, M.C.; Petersen, K.L. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 2007, 68, 515–521.

- Bennici, A.; Mannucci, C.; Calapai, F.; Cardia, L.; Ammendolia, I.; Gangemi, S.; Calapai, G.; Griscti Soler, D. Safety of Medical Cannabis in Neuropathic Chronic Pain Management. Molecules 2021, 26, 6257.

- Vinals, X.; Moreno, E.; Lanfumey, L.; Cordomi, A.; Pastor, A.; de La Torre, R.; Gasperini, P.; Navarro, G.; Howell, L.A.; Pardo, L.; et al. Cognitive Impairment Induced by Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol Occurs through Heteromers between Cannabinoid CB1 and Serotonin 5-HT2A Receptors. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002194.

- Gallo, M.; Moreno, E.; Defaus, S.; Ortega-Alvaro, A.; Gonzalez, A.; Robledo, P.; Cavaco, M.; Neves, V.; Castanho, M.; Casado, V.; et al. Orally Active Peptide Vector Allows Using Cannabis to Fight Pain While Avoiding Side Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6937–6948.

- Darmani, N.A. Cannabinoids of diverse structure inhibit two DOI-induced 5-HT(2A) receptor-mediated behaviors in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2001, 68, 311–317.

- Mechoulam, R.; Parker, L.A. The endocannabinoid system and the brain. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 21–47.

- Puighermanal, E.; Busquets-Garcia, A.; Maldonado, R.; Ozaita, A. Cellular and intracellular mechanisms involved in the cognitive impairment of cannabinoids. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 3254–3263.

- Bombardi, C.; Di Giovanni, G. Functional anatomy of 5-HT2A receptors in the amygdala and hippocampal complex: Relevance to memory functions. Exp. Brain Res. 2013, 230, 427–439.

- Shang, Y.; Tang, Y. The central cannabinoid receptor type-2 (CB2) and chronic pain. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 812–823.

- Bernal-Chico, A.; Tepavcevic, V.; Manterola, A.; Utrilla, C.; Matute, C.; Mato, S. Endocannabinoid signaling in brain diseases: Emerging relevance of glial cells. Glia 2023, 71, 103–126.

- Cabanero, D.; Ramirez-Lopez, A.; Drews, E.; Schmole, A.; Otte, D.M.; Wawrzczak-Bargiela, A.; Huerga Encabo, H.; Kummer, S.; Ferrer-Montiel, A.; Przewlocki, R.; et al. Protective role of neuronal and lymphoid cannabinoid CB(2) receptors in neuropathic pain. Elife 2020, 9, e55582.

- Curto-Reyes, V.; Llames, S.; Hidalgo, A.; Menendez, L.; Baamonde, A. Spinal and peripheral analgesic effects of the CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonist AM1241 in two models of bone cancer-induced pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 561–573.

- Pacher, P.; Batkai, S.; Kunos, G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 389–462.

- Pacher, P.; Kecskemeti, V. Trends in the development of new antidepressants. Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 925–943.

- Hen-Shoval, D.; Weller, A.; Weizman, A.; Shoval, G. Examining the Use of Antidepressants for Adolescents with Depression/Anxiety Who Regularly Use Cannabis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 523.

- Abuhasira, R.; Schleider, L.B.; Mechoulam, R.; Novack, V. Epidemiological characteristics, safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in the elderly. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 49, 44–50.

- Whiting, P.F.; Wolff, R.F.; Deshpande, S.; Di Nisio, M.; Duffy, S.; Hernandez, A.V.; Keurentjes, J.C.; Lang, S.; Misso, K.; Ryder, S.; et al. Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 313, 2456–2473.

- Graczyk, M.; Lukowicz, M.; Dzierzanowski, T. Prospects for the Use of Cannabinoids in Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 620073.

- Navarro, D.; Gasparyan, A.; Navarrete, F.; Torregrosa, A.B.; Rubio, G.; Marin-Mayor, M.; Acosta, G.B.; Garcia-Gutierrez, M.S.; Manzanares, J. Molecular Alterations of the Endocannabinoid System in Psychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4764.

- Monteleone, P.; Bifulco, M.; Maina, G.; Tortorella, A.; Gazzerro, P.; Proto, M.C.; Di Filippo, C.; Monteleone, F.; Canestrelli, B.; Buonerba, G.; et al. Investigation of CNR1 and FAAH endocannabinoid gene polymorphisms in bipolar disorder and major depression. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 61, 400–404.

- Minocci, D.; Massei, J.; Martino, A.; Milianti, M.; Piz, L.; Di Bello, D.; Sbrana, A.; Martinotti, E.; Rossi, A.M.; Nieri, P. Genetic association between bipolar disorder and 524A>C (Leu133Ile) polymorphism of CNR2 gene, encoding for CB2 cannabinoid receptor. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 134, 427–430.

- Mitjans, M.; Gasto, C.; Catalan, R.; Fananas, L.; Arias, B. Genetic variability in the endocannabinoid system and 12-week clinical response to citalopram treatment: The role of the CNR1, CNR2 and FAAH genes. J. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 26, 1391–1398.

- Domschke, K.; Dannlowski, U.; Ohrmann, P.; Lawford, B.; Bauer, J.; Kugel, H.; Heindel, W.; Young, R.; Morris, P.; Arolt, V.; et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CNR1) gene: Impact on antidepressant treatment response and emotion processing in major depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 18, 751–759.

- Micale, V.; Drago, F. Endocannabinoid system, stress and HPA axis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 834, 230–239.

- Sam, A.H.; Salem, V.; Ghatei, M.A. Rimonabant: From RIO to Ban. J. Obes. 2011, 2011, 432607.

- O’Brien, L.D.; Wills, K.L.; Segsworth, B.; Dashney, B.; Rock, E.M.; Limebeer, C.L.; Parker, L.A. Effect of chronic exposure to rimonabant and phytocannabinoids on anxiety-like behavior and saccharin palatability. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2013, 103, 597–602.

- Ettaro, R.; Laudermilk, L.; Clark, S.D.; Maitra, R. Behavioral assessment of rimonabant under acute and chronic conditions. Behav. Brain. Res. 2020, 390, 112697.

- Ashton, C.H.; Moore, P.B.; Gallagher, P.; Young, A.H. Cannabinoids in bipolar affective disorder: A review and discussion of their therapeutic potential. J. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 19, 293–300.

- Grinspoon, L.; Bakalar, J.B. The use of cannabis as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder: Anecdotal evidence and the need for clinical research. J. Psychoact. Drugs 1998, 30, 171–177.

- Botsford, S.L.; Yang, S.; George, T.P. Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Impact on Illness Onset and Course, and Assessment of Therapeutic Potential. Am. J. Addict. 2020, 29, 9–26.

- Grinchii, D.; Dremencov, E. Mechanism of Action of Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs in Mood Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9532.