Due to their different properties compared to other materials, nanoparticles of iron and iron oxides are increasingly used in the food industry. Food technologists have especially paid attention to their ease of separation by magnetic fields and biocompatibility. Compared to other metallic NPs, iron nanoparticles are widely used. This is determined by such properties as their small size, superparamagnetism and biocompatibility. Iron nanoparticles are used in bioprocessing, tissue engineering and other aspects of modern medicine. There are different oxide forms of iron, such as hematite (α-Fe2O3), maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), FeOH (OH) goethite and magnetite (Fe3O4). The most commonly used crystalline iron oxide structures are maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) and magnetite (Fe3O4). They are used in many fields, including magnetic data storage, pigment production for electrochemistry, contrast production and many others.

- iron nanoparticles

- food packaging

- antimicrobial effects

1. Application in the Production of Food Packaging

2. Edible Coatings on Food

3. Immobilization of Enzymes

4. Artificial Enzymes

5. Food Analysis

| Food Type | Analyzed Substance/Organism | Material for Functionalized IONPs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thai food | Cu(II) | chitosan–graphene quantum dots | [30] |

| milk and honey | sulfamethoxazole | molecularly imprinted polymers | [31] |

| fish, shrimp, canned tuna | Hg(II) | SiO2@polythiophene | [32] |

| cantaloupe, apple, nectarine | Cd(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) | 2-aminobenzothiazole | [33] |

| milk | melamine | SiO2@MIPs | [34] |

| vegetable oil | pesticide | polystyrene | [35] |

| canned tuna fish, canned tomato paste, parsley, milk | Pb(II) | 3-aminopropyl-trie- thoxysilane@ phthalic anhydride |

[36] |

| candies and beverages | synthetic colorants | polyethyleneimine | [37] |

| sausage | nitrate | Au@l-cysteine | [38] |

| milk | Salmonella typhimurium | CdSe/ZnS QDs with NH 2−PEG−CM(MW 3400) as spacers to be conjugated withantibodies |

[39] |

| milk | Listeria monocytogenes | carboxyl with rabbit anti-Listeria monocytogenes | [40] |

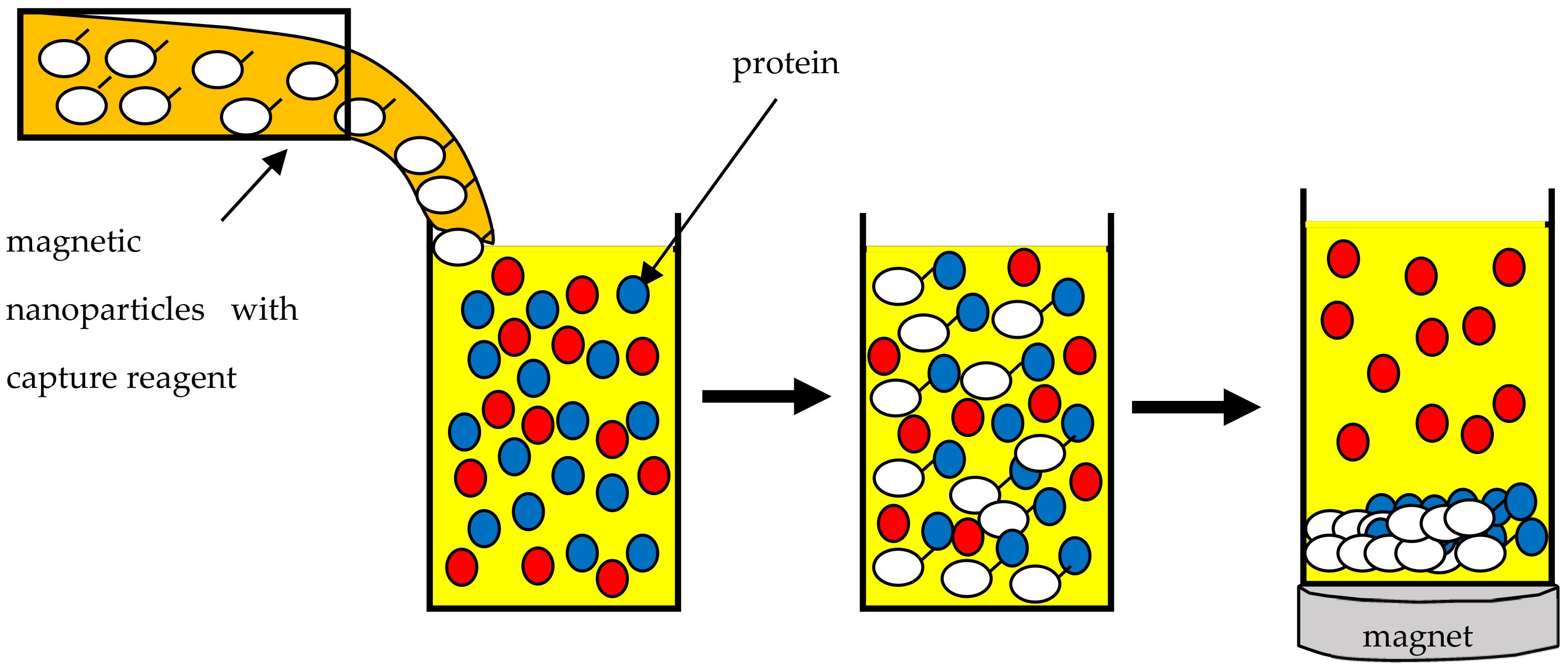

6. Protein Purification

7. Iron Oxides as Ingredients in Foods and Dietary Supplements

8. Colorants

9. Mycotoxin Removal

10. Anti-Allergic Effect

11. Control of the Process Flow

12. Preservation of Food in Supercooled State

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ma16020780

References

- Keshk, S.M.A.S.; El-Zahhar, A.A.; Abu Haija, M.; Bondock, S. Synthesis of a Magnetic Nanoparticles/Dialdehyde Starch-Based Composite Film for Food Packaging. Starch/Staerke 2019, 71, 1800035.

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Salehabadi, A.; Nafchi, A.M.; Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Jafari, S.M. Cheese packaging by edible coatings and biodegradable nanocomposites; improvement in shelf life, physicochemical and sensory properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 218–231.

- Mu, H.; Gao, H.; Chen, H.; Tao, F.; Fang, X.; Ge, L. A nanosised oxygen scavenger: Preparation and antioxidant application to roasted sunflower seeds and walnuts. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 245–250.

- Foltynowicz, Z.; Bardenshtein, A.; Sängerlaub, S.; Antvorskov, H.; Kozak, W. Nanoscale, zero valent iron particles for application as oxygen scavenger in food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2017, 11, 74–83.

- Vilela, C.; Kurek, M.; Hayouka, Z.; Röcker, B.; Yildirim, S.; Antunes, M.D.C.; Nilsen-Nygaard, J.; Pettersen, M.K.; Freire, C.S.R. A concise guide to active agents for active food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 212–222.

- Busolo, M.A.; Lagaron, J.M. Oxygen scavenging polyolefin nanocomposite films containing an iron modified kaolinite of interest in active food packaging applications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012, 16, 211–217.

- EFSA Panel on Food Contact Materials, Enzymes, Flavourings and Processing Aids (CEF). Scientific Opinion on the safety assessment of the active substances iron, iron oxides, sodium chloride and calcium hydroxide for use in food contact materials. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3387.

- Khalaj, M.-J.; Ahmadi, H.; Lesankhosh, R.; Khalaj, G. Study of physical and mechanical properties of polypropylene nanocomposites for food packaging application: Nano-clay modified with iron nanoparticles. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 41–48.

- Mary, T.R.N.; Jayavel, R. Fabrication of chitosan/Cashew Nut Shell Liquid/plant extracts-based bio-formulated nanosheets with embedded iron oxide nanoparticles as multi-functional barrier resist eco-packaging material. Appl. Nanosci. 2022, 12, 1719–1730.

- Ligaj, M.; Tichoniuk, M.; Cierpiszewski, R.; Foltynowicz, Z. Efficiency of Novel Antimicrobial Coating Based on Iron Nanoparticles for Dairy Products’ Packaging. Coatings 2020, 10, 156.

- Song, Z.; Niu, C.; Wu, H.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, T. Transcriptomic Analysis of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Antibacterial Activity of Composites toward Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21874–21886.

- Zhu, N.; Ji, H.; Yu, P.; Niu, J.; Farooq, M.U.; Akram, M.W.; Udego, I.O.; Li, H.; Niu, X. Surface Modification of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 810.

- Kumar, S.; Ye, F.; Dobretsov, S.; Dutta, J. Chitosan Nanocomposite Coatings for Food, Paints, and Water Treatment Applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2409.

- Bahrami, A.; Delshadi, R.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M.; Williams, L. Antimicrobial-loaded nanocarriers for food packaging applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 278, 102140.

- Singh, T.P.; Chatli, M.K.; Sahoo, J. Development of chitosan based edible films: Process optimization using response surface methodology. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 2530–2543.

- Nehra, P.; Chauhan, R.; Garg, N.; Verma, K. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of chitosan coated iron oxide nanoparticles. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 75, 13–18.

- Shrifian-Esfahni, A.; Salehi, M.T.; Nasr-Esfahni, M.; Ekramian, E. Chitosan-Modified Superparamgnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Design, Fabrication, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity. Chemik 2015, 69, 19–32.

- Niemirowicz, K.; Markiewicz, K.; Wilczewska, A.; Car, H. Magnetic nanoparticles as new diagnostic tools in medicine. Adv. Med. Sci. 2012, 57, 196–207.

- Lattuada, M.; Hatton, T.A. Functionalization of Monodisperse Magnetic Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2007, 23, 2158–2168.

- Bashir, N.; Sood, M.; Bandral, J.D. Enzyme immobilization and its applications in food processing: A review. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2020, 8, 254–261.

- Díaz-Hernández, A.; Gracida, J.; García-Almendárez, B.E.; Regalado, C.; Núñez, R.; Amaro-Reyes, A. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticles Coated with Chitosan: A Potential Approach for Enzyme Immobilization. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 9468574.

- Xu, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, J.; Wang, F.; Sun, M. Application of Iron Magnetic Nanoparticles in Protein Immobilization. Molecules 2014, 19, 11465–11486.

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Lou, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Wei, H. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): Next-generation artificial enzymes (II). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1004–1076.

- Gao, L.; Fan, K.; Yan, X. Iron Oxide Nanozyme: A Multifunctional Enzyme Mimetic for Biomedical Applications. Theranostics 2017, 7, 3207–3227.

- Qin, T.; Ma, R.; Yin, Y.; Miao, X.; Chen, S.; Fan, K.; Xi, J.; Liu, Q.; Gu, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. Catalytic inactivation of influenza virus by iron oxide nanozyme. Theranostics 2019, 9, 6920–6935.

- You, S.-M.; Park, J.-S.; Luo, K.; Jeong, K.-B.; Adra, H.J.; Kim, Y.-R. Modulation of the peroxidase-like activity of iron oxide nanoparticles by surface functionalization with polysaccharides and its application for the detection of glutathione. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118164.

- Hernández-Hernández, A.A.; Álvarez-Romero, G.A.; Contreras-López, E.; Aguilar-Arteaga, K.; Castañeda-Ovando, A. Food Analysis by Microextraction Methods Based on the Use of Magnetic Nanoparticles as Supports: Recent Advances. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2974–2993.

- Speroni, F.; Elviri, L.; Careri, M.; Mangia, A. Magnetic Particles Functionalized with PAMAM-Dendrimers and Antibodies: A New System for an ELISA Method Able to Detect Ara H3/4 Peanut Allergen in Foods. In Proceedings of the Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 397, pp. 3035–3042.

- Cao, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Ge, W.; Yue, T.; Li, R.; Colvin, V.L.; Yu, W.W. Food related applications of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Enzyme immobilization, protein purification, and food analysis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 27, 47–56.

- Limchoowong, N.; Sricharoen, P.; Areerob, Y.; Nuengmatcha, P.; Sripakdee, T.; Techawongstien, S.; Chanthai, S. Preconcentration and trace determination of copper (II) in Thai food recipes using Fe3O4 @Chi–GQDs nanocomposites as a new magnetic adsorbent. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 388–397.

- Zhao, Y.; Bi, C.; He, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of molecularly imprinted polymers based on magnetic carbon nanotubes for determination of sulfamethoxazole in food samples. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 70309–70318.

- Abolhasani, J.; Khanmiri, R.H.; Babazadeh, M.; Ghorbani-Kalhor, E.; Edjlali, L.; Hassanpour, A. Determination of Hg(II) ions in sea food samples after extraction and preconcentration by novel Fe3O4@SiO2@polythiophene magnetic nanocomposite. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 1–11.

- Bagheri, H.; Asgharinezhad, A.A.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Determination of Trace Amounts of Cd(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) in Food Samples Using a Novel Functionalized Magnetic Nanosorbent. Food Anal. Methods 2016, 9, 876–888.

- He, D.; Zhang, X.; Gao, B.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C. Preparation of magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer for the extraction of melamine from milk followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Control. 2014, 36, 36–41.

- Yu, X.; Ang, H.C.; Yang, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, Y. Low temperature cleanup combined with magnetic nanoparticle extraction to determine pyrethroids residue in vegetables oils. Food Control. 2017, 74, 112–120.

- Pirouz, M.J.; Beyki, M.H.; Shemirani, F. Anhydride functionalised calcium ferrite nanoparticles: A new selective magnetic material for enrichment of lead ions from water and food samples. Food Chem. 2015, 170, 131–137.

- Chen, H.; Deng, X.; Ding, G.; Qiao, Y. The synthesis, adsorption mechanism and application of polyethyleneimine functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the analysis of synthetic colorants in candies and beverages. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 340–347.

- Yu, C.; Guo, J.; Gu, H. Electrocatalytical Oxidation of Nitrite and Its Determination Based on 3O4 Nanoparticles. Electroanalysis 2010, 22, 1005–1011.

- Wen, C.-Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Ou, G.-P.; Liao, Y.-L.; Li, Y.; Xie, M.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Pang, D.-W. One-Step Sensitive Detection of Salmonella typhimurium by Coupling Magnetic Capture and Fluorescence Identification with Functional Nanospheres. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 1223–1230.

- Yang, H.; Qu, L.; Wimbrow, A.N.; Jiang, X.; Sun, Y. Rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes by nanoparticle-based immunomagnetic separation and real-time PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 118, 132–138.

- Yang, K.; Jenkins, D.M.; Su, W.W. Rapid concentration of bacteria using submicron magnetic anion exchangers for improving PCR-based multiplex pathogen detection. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 86, 69–77.

- Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Gan, M.; Xu, F.; He, L.; Yang, D.; Xu, H.; Shah, N.P.; Wei, H. Rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy and meat foods by combination of capture with silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles and thermophilic helicase-dependent isothermal amplification. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 1563–1570.

- Gravel, A.; Doyen, A. The use of edible insect proteins in food: Challenges and issues related to their functional properties. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 59, 102272.

- Khan, S.; Roser, D.; Davies, C.; Peters, G.; Stuetz, R.; Tucker, R.; Ashbolt, N. Chemical contaminants in feedlot wastes: Concentrations, effects and attenuation. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 839–859.

- Gao, R.; Cui, X.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, D.; Tang, Y. A highly-efficient imprinted magnetic nanoparticle for selective separation and detection of 17β-estradiol in milk. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1040–1047.

- Luo, Y.-B.; Yu, Q.-W.; Yuan, B.-F.; Feng, Y.-Q. Fast microextraction of phthalate acid esters from beverage, environmental water and perfume samples by magnetic multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Talanta 2012, 90, 123–131.

- Dave, S.R.; Gao, X. Monodisperse magnetic nanoparticles for biodetection, imaging, and drug delivery: A versatile and evolving technology. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009, 1, 583–609.

- Kumari, A.; Chauhan, A.K. Iron nanoparticles as a promising compound for food fortification in iron deficiency anemia: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 59, 3319–3335.

- Von Moos, L.M.; Schneider, M.; Hilty, F.M.; Hilbe, M.; Arnold, M.; Ziegler, N.; Mato, D.S.; Winkler, H.; Tarik, M.; Ludwig, C.; et al. Iron phosphate nanoparticles for food fortification: Biological effects in rats and human cell lines. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 496–506.

- Arami, H.; Khandhar, A.; Liggitt, D.; Krishnan, K.M. In vivo delivery, pharmacokinetics, biodistribution and toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8576–8607.

- Perfecto, A.; Elgy, C.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Sharp, P.; Hilty, F.; Fairweather-Tait, S. Mechanisms of Iron Uptake from Ferric Phosphate Nanoparticles in Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells. Nutrients 2017, 9, 359.

- Hilty, F.M.; Knijnenburg, J.T.; Teleki, A.; Krumeich, F.; Hurrell, R.F.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Zimmermann, M.B. Incorporation of Mg and Ca into Nanostructured Fe2O3 Improves Fe Solubility in Dilute Acid and Sensory Characteristics in Foods. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, N2–N10.

- Mufti, N.; Atma, T.; Fuad, A.; Sutadji, E. Synthesis and Characterization of Black, Red and Yellow Nanoparticles Pigments from the Iron Sand. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 1617, pp. 165–169.

- Voss, L.; Hsiao, I.-L.; Ebisch, M.; Vidmar, J.; Dreiack, N.; Böhmert, L.; Stock, V.; Braeuning, A.; Loeschner, K.; Laux, P.; et al. The presence of iron oxide nanoparticles in the food pigment E172. Food Chem. 2020, 327, 127000.

- Alshannaq, A.; Yu, J.-H. Occurrence, Toxicity, and Analysis of Major Mycotoxins in Food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 632.

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in Occurrence, Importance, and Mycotoxin Control Strategies: Prevention and Detoxification in Foods. Foods 2020, 9, 137.

- Horky, P.; Skalickova, S.; Baholet, D.; Skladanka, J. Nanoparticles as a Solution for Eliminating the Risk of Mycotoxins. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 727.

- Castro, S.S.L.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Stradiotto, N.R. Study of the Electrochemical Behavior of Histamine Using a Nafion®-Copper (II) Hexacyanoferrate Film-Modified Electrode. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2010, 5, 1447–1456.

- Adivi, F.G.; Hashemi, P. Removal of histamine from biological samples by functionalized Fe3O4@ nanoparticles and its fast determination by ion mobility spectrometry. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 203, 111717.

- Ranmadugala, D.; Ebrahiminezhad, A.; Manley-Harris, M.; Ghasemi, Y.; Berenjian, A. The effect of iron oxide nanoparticles on Bacillus subtilis biofilm, growth and viability. Process. Biochem. 2017, 62, 231–240.

- Kobayashi, A.; Horikawa, M.; Kirschvink, J.L.; Golash, H.N. Magnetic control of heterogeneous ice nucleation with nanophase magnetite: Biophysical and agricultural implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5383–5388.

- Kang, T.; Hoptowit, R.; Jun, S. Effects of an oscillating magnetic field on ice nucleation in aqueous iron-oxide nanoparticle dispersions during supercooling and preservation of beef as a food application. J. Food Process. Eng. 2020, 43, e13525.