Photocatalysis has been found to be a practical, environmentally friendly approach for degrading various pollutants into non-toxic products (e.g., H2O and CO2) and generating fuels from water using solar light. Mainly, traditional photocatalysts (such as metal oxides, sulfides, and nitrides) have shown a promising role in various photocatalysis reactions. However, it faces many bottlenecks, such as a wider band gap, low light absorption nature, photo-corrosion issues, and quick recombination rates. Due to these, a big question arises of whether these traditional photocatalysts can meet increasing energy demand and degrade emerging pollutants in the future. Currently, researchers view heteroanionic materials as a feasible alternative to conventional photocatalysts for future energy generation and water purification techniques due to their superior light absorption capacity, narrower band gap, and improved photo-corrosion resistance. Therefore, this entry summarizes the recent developments in heteroanionic materials, their classifications based on anionic presence, their synthesis techniques, and their role in photocatalysis. In the end, we present a few recommendations for improving the photocatalytic performance of future heteroanionic materials.

- heteroanionic photocatalysts

- photocatalysis

- water purification

1. Introduction

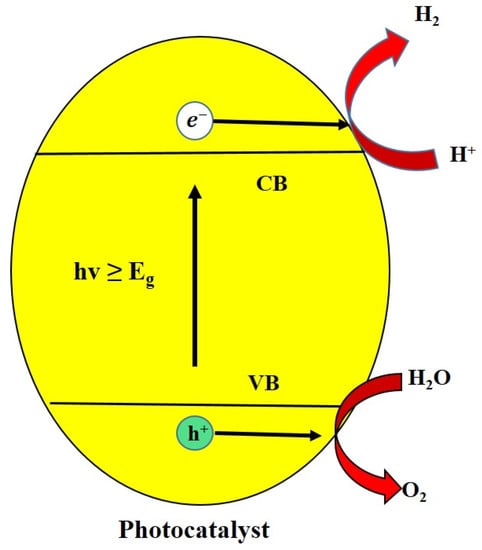

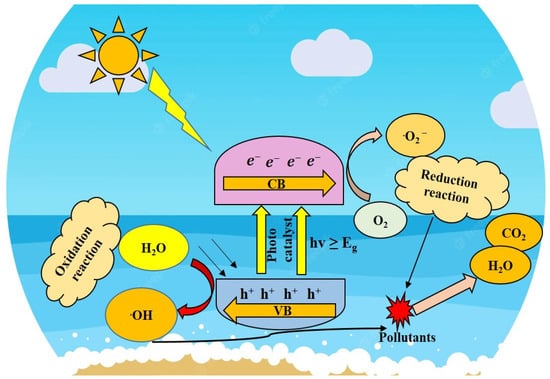

2. Photocatalysis and Its Mechanism

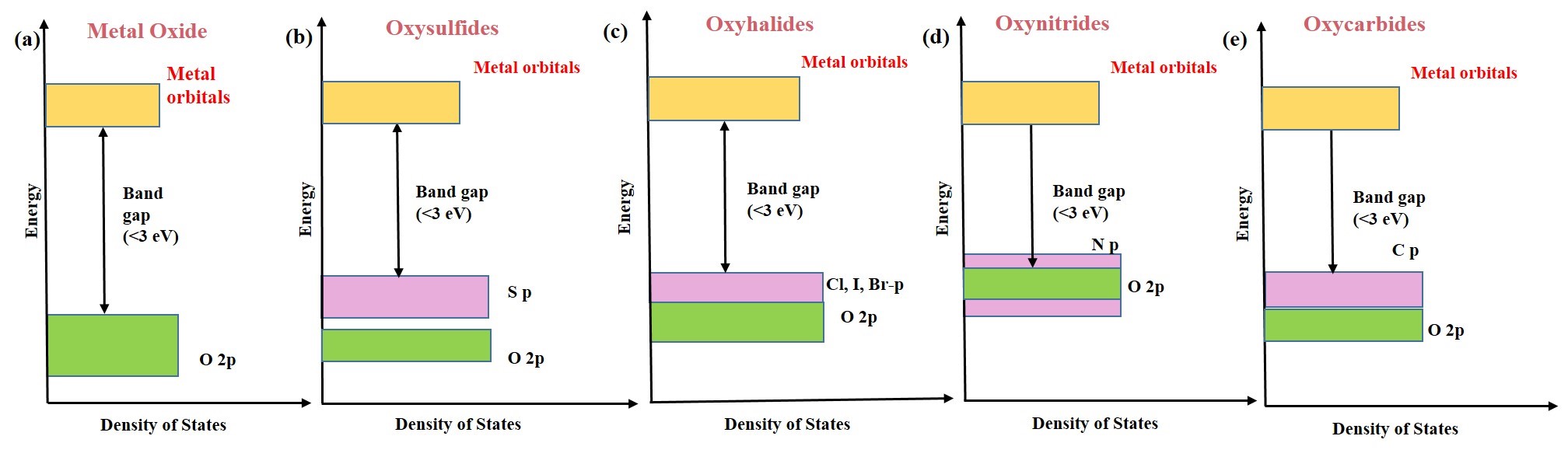

Heteroanionic engineering is an emerging technique for producing more efficient photocatalysts than conventional photocatalysts. Heteroanionic photocatalysts have more than one anion in their structure [31,32]. Its electrical and thermal properties can be easily adjustable, and its oxidation resistance, chemical inertness, and photon absorption are exceptional [33,34]. It has a smaller band gap than metal oxide complexes because of the lower electronegativity of non-oxide anions in its structure, which facilitates more excellent visible-light absorption [35,36].[59,60]. Heteroanionic photocatalysts can be classified based on the anionic present in their structure, such as metal oxynitrides (MOxNy), oxysulfides (MxOySz), oxyhalides (MOX), oxycarbides (MOyCz)[14]. The VB of the heteroanionic photocatalysts is occupied by hybridized anion/oxygen atoms p-orbitals, while its CB is made up of empty d0 or d10 orbitals of metal ions. This configuration induces a smaller band gap with a more negative VB than conventional metal oxides/sulfides/nitrides photocatalysts. These photocatalysts can be synthesized by mixing several anions using various strategies such as electronic/crystal structure engineering and local coordination geometry [37,38]. Heteroanionic photocatalysts produced via in-situ chemical solution procedures have greater efficiencies than those synthesized through physical mixing techniques. Recently, heteroanionic photocatalysts exhibited higher efficiency, principally attributable to the greater separation of electron–hole pairs via interfacial charge transfer and its lower band gap energy. Consequently, the interface between various anions in heteroanionic materials serves as the crucial charge-carrier transfer route during photocatalysis. Due to their stability and high efficiency, these materials have recently created incredible interest in photocatalysis as both catalysts and supports. Figure 3 (a-e) compares the electronic structure of metal oxides with various types of heteroanionic photocatalysts.

Figure 3. Comparison of the electronic structure of (a) metal oxides with (b) oxysulfides, (c) oxyhalides, (e) oxynitrides, and (e) oxycarbides photocatalysts.

4. Classification of Heteroanionic Photocatalyst

4.1. Oxynitride-Based Photocatalyst

Metal oxynitrides are one of the emerging photocatalysts that possess combined characteristics of their oxides and nitrides. Oxynitrides photocatalysts mainly have metal cations as the primary element connected with oxygen and nitrogen atoms [39,40,41]. The VB of these materials is occupied by hybridized N-2p and O-2p orbitals [66,67]. Its conduction band was made up of d0 or d10 orbitals of metal ions; this arrangement induces a smaller band gap with more negative VB than conventional metal oxide/nitride photocatalysts [34,42]. Its band gap structure, good electrical conductivity, and corrosion-resistant characteristics favor photocatalysis. Oxynitrides are more stable in air and moisture than bare nitrides [43]. Pure nitrides are more sensitive to visible and UV light than oxide materials; however, they predominantly suffer from stability issues and cannot maintain their photocatalytic character for a long time. Therefore, researchers attempted to introduce nitrogen into the oxide network to obtain superior physical and chemical characteristics compared to metal oxide and nitride materials. Nitrogen atoms are less electronegative and more polarizable than oxygen atoms, so replacing nitrogen with oxygen helps to narrow down the band gap between the anion-based VB and cation-based CB [70]. Most oxynitrides have suitable band gap values between 1.6-3.3 eV, as necessary for various photocatalytic reactions [38,44]. The following section discusses essential oxynitride-based materials, their synthesis process, and their photocatalytic character.

The synthesis process of oxynitride-based materials is very complex compared to oxide materials. A significant nitriding candidate is needed to prepare oxynitrides photocatalysts from oxide precursors. The most common method for fabricating oxynitrides is thermal ammonolysis [45]. Here, ammonia plays both roles of nitriding (oxidizing) and reducing agent; this dual character is most crucial for the ammonolysis reaction [46]. When the ammonia passes over the oxide precursor, it decomposes over the oxide surface by creating reactive nitriding candidates (N, NH, NH2) in a native state and H2 [47]. Then the hydrogen reacts with oxygen atoms from the oxide precursor and escapes as water vapors. This thermodynamic reaction acts as a driving force to introduce nitrogen through the substitution approach, as shown in Equation (12)[48].

|

Oxide + NH3 (g) → Oxynitride + H2O |

(12) |

High pressure is supplied to this process to avoid the decomposition of precursors such as oxides and nitrogen gas. It helps to stabilize the oxynitrides with novel structures at moderate temperatures. Only a few solid-state syntheses of oxynitrides at high pressures have been studied in the literature [49]. The temperature supplied to this process mainly depends upon the choice of the chosen oxide precursor. The purity of the oxynitride phase primarily depends upon the proper control over vital parameters such as temperature, ammonia flow rate, the pressure inside the alumina tube, reaction time, and type of oxide precursor kept inside the alumina tube. Similarly, some oxynitrides have been fabricated in thin films via physical and chemical approaches. For example, thin films of BaTaO2N have been prepared through pulsed laser deposition [50], and also thin films of LaTiO2N have been obtained via reactive RF-magnetron sputtering to analyze its photocatalytic performance [51].

In particular, tantalum oxynitride is a promising heteroanionic photocatalyst that possesses suitable valence and conduction band edges to generate H2 and O2 from water [52]. It has narrower band gap energy than tantalum oxide [53,54]. As a result, it captures visible light more efficiently and has improved photocatalytic capability. Its crystal structure is monoclinic, where tantalum is hepta-coordinated and interconnected with N and O anions. For instance, Domen et al. explored the photocatalytic characteristics of TaON [55]. It demonstrated a quantum efficiency of 34% for oxygen evolution in the presence of a sacrificial reagent because it has a maximum visible-light absorption capability of up to ~530 nm, with a VB edge of 2.20 eV vs. SHE. It was prepared by heating the Ta2O5 on tantalum foil at 1073–1123 K under an ammonia flow of 10 mL min−1. Apart from TaON, most d0 metal oxynitride belongs to a subgroup named perovskite oxynitrides. Generally, perovskite-structured materials possess promising properties in terms of electric conductivity, light absorption, and high photostability. Perovskite-based oxynitrides (ABO2N) can be formed by adding nitrogen into the anionic network of the corresponding oxides [56]. It consists of the irregular, corner-shared BO(N)6 octahedra joined by metal cations. It can result in materials with a narrower band gap than the parent oxide. This narrowing happened due to the inclusion of higher energy N-2p orbital along with the O-2p orbital in VB of the parent oxide, making them excellent candidates for visible light-absorbing photocatalysts. The general formula for perovskite oxynitride is termed as ABO2xN1+x [57]. Ammonolysis is the most common process for producing perovskite-based oxynitrides. Perovskite-type compounds (ABO2N) are often synthesized by heating the oxide precursors (A2B2O7) or mixes of oxides and oxysalts, such as carbonates in the presence of ammonia in the temperature range of 600–1100 °C [46]. Perovskite oxynitrides such as CaTaO2N, SrTaO2N, LaTaON2, and BaNbO2N oxynitride perovskite also showed promising photocatalytic characteristics [58]. Their band gap and edge positions offered significant activity over water oxidation and reduction processes. The results of the above-reported investigations demonstrated that metal oxynitride could be made more robust through surface and interface modification. These modifications enhance the durability of metal oxynitride by regulating h+ extraction and driving them to realize as visible-light absorption catalysts. Future developments that strengthen the endurance of metal oxynitrides may be achievable by understanding how durability can be engineered in future heteroanionic materials.

4.2. Oxyhalide-Based Photocatalyst

Metal oxyhalides (MOX) have played a potential role in solar–fuel generation and water purification processes due to their promising energy band gap structure and light absorption properties [59,60]. These characteristics mainly depend upon the type of halide engineered in its structure. Bismuth oxyhalides - BiOX (X = Cl-3p, Br-4p, I-5p) are the most commonly employed heteroanionic catalysts due to their easy band gap tuning nature [61,62]. The visible-light absorption character of BiOX dramatically depends upon the size of the halogen ion. If the size of the halogen increases, its polarizability character also increases from Cl to I. These compounds are composed of [Bi2O2]+2 layers between double slabs of halogen atoms [63,64]. This kind of arrangement induces an internal electric field within the BiOX structure. The internally generated electric field improves the lifetime of photogenerated electron–hole pairs and reduces the recombination rate when irradiated by the light of appropriate energy [65,66]. BiOX-based photocatalysts show some favorable characteristics, such as chemically stable, non-toxic, and anti-corrosive nature [67]. Furthermore, BiOX materials are more sensitive and responsive to visible light than UV light due to their narrower band gap [68]. The VB maxima of BiOX compounds are comprised of O-2p and X-p orbitals, whereas their CB maxima consist of Bi-6p orbitals [69,70,71]. BiOCl has a wider band gap value of 3.2 eV and demonstrates a significant photocatalytic character under UV light [72].

Similarly, BiOBr (2.64 eV) has a suitable band gap and redox potential, which encourages the conversion of the oxygen molecule into 𝑶𝟐− radicals and H2 into H+ ions [73,74]. However, BiOI is very complex to attain the redox potential due to its narrow band gap value of 1.77 eV [68,75]. The most common techniques for producing BiOX are hydrothermal [76], calcination [77], precipitation [78], microwave [79], reverse micro-emulsion [80], sonochemical methods [81], and template approaches [82]. These approaches helped to enhance visible-light absorption and photocatalytic character. In terms of photocatalytic activity, bismuth oxyhalides provided better performance in all kinds of photocatalytic processes such as hydrogen generation, CO2 reduction, pollutant removal from water sources, nitrogen fixation, etc.,[83,84,85,86] It has been found that most research reports on oxyhalide materials available were based only on BiOX-based photocatalysts. Hence, it is necessary to fabricate a new type of oxyhalide-based photocatalysts (such as NbOCl, VOCl3, etc.) to employ them in the degradation process of environmental pollutants and solar-fuel generation and make them more accessible in the future.

4.3. Oxysulfide-Based Photocatalyst

Oxysulfide photocatalyst has a chemical composition between the oxide and chalcogen photocatalysts [87]. It possesses at least a metal, oxygen, and sulfur in its crystal structure with negative oxidation states for both O and S [88]. It is an independent group from metal oxide and metal sulfide. It can be coined with the generic formula MxOySz. Their VB is composed of the sulfur and oxygen orbitals, and d0/d10-metal ion orbitals occupy the conduction band (e.g., SrZn2S2O, Ln2Ti2S2O5, etc.) [89]. It possesses narrower bandgaps that are more favorable for photocatalytic water splitting under visible-light exposure due to its sulfide ions, which shift its valence band edges to the negative potential. Most oxysulfide is not available in nature; it needs to be synthesized. In 1947, Pitha and their team fabricated the first crystalline oxysulfide called La2O2S [90], and in 1949, Zachariasen synthesized some La2O2S, Ce2O2S, and Pu2O2S [91]. For instance, La2O2S can be made by reducing Ln2(SO4)3 using hydrogen gas or heating the Ln2S3 in the presence of air. It has been found that La2O2S is made up of one metal atom that was interconnected with four atoms of oxygen and three atoms of sulfur with a space group of P-3m1. Most metal oxysulfides are fabricated by treating the oxide precursors with sulfur/metal sulfide. However, the band gap tuning of oxysulfide is very complex by varying stoichiometric ratios because sulfur has larger atomic radii than oxygen.

Metal sulfides such as CdS and ZnS generally show excellent absorption in visible light. It has the capacity to generate a considerable amount of H2 through the photoreduction of H+ ions with the support of the electron donors such as S2 and SO32−. The significant bottlenecks of metal sulfide are subjected to photo-corrosion, because S2− anions are sensitive to oxidation by photogenerated holes [92]. These drawbacks can be rectified by synthesizing more stable oxysulfide compounds [93]. For instance, Wang and their team prepared Y2Ti2O5S2 through a solid-state reaction with tetragonal symmetry [16]. It possesses a narrower band gap energy of 1.9 eV, which absorbs a massive region of solar radiation even up to the wavelength of 650 nm. The conduction and valence band maximum of prepared Y2Ti2O5S2 lies between 1.1 to −1.0 V and 0.8–0.9 V versus SHE, respectively. It has been found that Ti-3d orbitals occupy their CBM, whereas VBM is mixed up with O-2p, S-3p, and Y-3d orbitals. Their band edge positions favored H2 and O2 generation via photocatalytic water splitting. These photocatalysts produced considerable hydrogen and oxygen gas when supported with IrO2 and Rh/Cr2O3 during the oxygen and hydrogen evolution process by maintaining pH values around 8–9. During the photocatalysis study, it was found that Y2Ti2O5S2 has more chemical and photostability. Similarly, various types of oxysulfide photocatalysts such as SrZn2S2O, Ag-InOS, etc., [88,94,95,96] were created to role their photocatalytic behavior. It was found that oxysulfide photocatalysts can perform better than their sulfide-based compounds. Based on the available reports, it was found that research on oxysulfide catalysts is significantly less than on other heteroanionic materials. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new oxysulfide compounds to increase their catalytic studies because sulfide-based materials generally possess promising characteristics. Furthermore, attempts such as surface modification should be made on the oxysulfide materials to improve their catalytic efficiency via loading suitable co-catalysts (apart from pt), ion doping, coupling with carbon materials, hetero-junction engineering, etc. It helps to extract h+/e− from oxysulfide and induce a strong hybridization between S- and O-orbitals near the VBM.

4.4. Oxycarbide-Based Photocatalyst

Oxycarbide-based materials are among the newest photocatalysts; they contain a metal ion linked to oxygen and carbon atoms [97]. Their electrical and thermal properties are easily modifiable, and their oxidation resistance, chemical inertness, and photon absorption are exceptional. They exhibit a small band gap structure. The VB of these materials is occupied by mixed C-2p and O-2p orbitals, while its CB is composed of empty d orbitals of metal ions [19][20]. This configuration induces a smaller band gap with a more negative VB than conventional metal oxide photocatalysts [98]. It can be obtained by regulating the calcination temperature and environment in a complex manner during the synthesis process. Due to their stability and high capacity, most oxycarbide-based compounds were utilized as anodes in the batteries [99,100,101]. Compared to typical photocatalysts, their preparation procedures are pretty tricky. Moreover, a strong interface between various anions in oxycarbide plays a significant role in photocatalytic degradation by enhancing its charge-carrier transfer route. According to our knowledge, oxy-carbides are utilized as a photocatalyst only in fewer papers. Even though oxycarbide compounds have intriguing properties, their synthesis processes are more complex than conventional photocatalysts. Therefore, it is necessary to create low-cost green synthetic methods with precise control over the anion stoichiometry to synthesize oxycarbide materials at a wide scale. This trend supports us in having a more profound knowledge of how to control the surface morphology of these materials and their creation, which helps to enhance their fundamental characteristics in the future.

5. Advantages of the Heteroanionic Photocatalyst

- Promising optical absorption property: Heteroanionic photocatalysts may absorb both visible and ultraviolet light effectively in order to drive an electron from VB to CB. Heteroanionic photocatalysts capture the visible portion of sunlight more efficiently than conventional photocatalysts [102,103].

- High diffusion rate: The electrons and holes in CB and VB of heteroanionic photocatalysts diffuse more rapidly from the bulk to the surface than traditional ones [104,105].

- Reasonable surface charge transfer property: Heteroanionic photocatalysts possess good surface charge transfer capability, interact well with various contaminants, and prolong charge-carrier recombination time [106,107].

- Effective oxygen utilization: Heteroanionic photocatalysts effectively utilize atmospheric oxygen as an oxidant; no additional oxidant is required [107,108].

- Utilize less UV Light: Heteroanionic materials utilize low-energy UV light to activate their photocatalytic properties [89].

- High stability: Heteroanionic photocatalysts are inexpensive, less toxic, stable, physiologically and chemically inert, largely insoluble, and recyclable [109].

- Limitations of the Heteroanionic Photocatalyst

- Even though heteroanionic materials possess a narrower band than conventional photocatalysts, they still face quick recombination of the charge carriers during some catalytic reactions.

- Most heteroanionic materials employ expensive material (platinum) as a co-catalyst during hydrogen generation, which inevitably raises their synthesis costs.

- Current synthesis methods adopted for preparation for heteroanionic materials are very complex and do not possess precise control over the anion stoichiometry.

- Many heteroanionic materials are found to be potentially fit for photocatalysis, but they are utilized very rarely in catalytic reactions such as nitrogen fixation and CO2 reduction compared to conventional catalysts.

- Conclusions and Future Outlook

Energy harvesting from long-lasting sunlight has proven to be a promising answer to the world’s energy needs and pollutant degradation. In the last few decades, most photocatalysts utilized for photocatalysis were basically made up of metal oxides/sulfides/nitrides. In recent days, heteroanionic photocatalysts that perform the same function with greater efficiency have accelerated research when compared with conventional catalysts. Heteroanionic photocatalysts were found to have a narrower band gap, which facilitates electron excitation when exposed to sunlight. In addition, these photocatalysts have a large surface area and small particle size, resulting in a low recombination rate. In this regard, we have emphasized the most recent developments of four types of heteroanionic photocatalysts, including oxynitride, oxysulfide, oxycarbide, and oxyhalide. Based on this entry, we made a few recommendations and prospects to improve heteroanionic materials to advance photocatalysis technology further.

- Simple and effective synthesis methods: Although these materials have intriguing properties, most of their synthesis processes are more complex than conventional photocatalysts. Hence, it is necessary to create low-cost green synthetic methods to fabricate these photocatalysts on a wide scale at a high-efficiency level. For example, Xin-de tang et al. mainly adopted a simple approach to prepare a La3NbS2O5 by varying its sulfurization time and synthesis temperatures [110]. It reduced preparation time to 1 h compared to the conventional synthesis process (which takes nine days).

- Theoretical analysis: Theoretical computations on the band gap and energy level of heteroanionic photocatalysts would provide theoretical guidance for building the desired structure and selecting suitable matching elements. For the fabrication of heteroanionic photocatalysts, a combination of experiment and computation approach is most required. Notably, DFT-based first-principles calculations can be employed to investigate the characteristics of these materials and to gain a deeper understanding of the roles of the various components in the photocatalytic mechanism.

- Developing new and cost-effective co-catalysts: It is essential to fabricate novel and cost-effective co-catalysts that can effectively extract h+/e− from heteroanionic materials during catalytic reactions.

- Doping and Heterostructures: The photocatalytic efficiency of heteroanionic materials can be enhanced further through various approaches such as metal and non-metal doping, oxygen vacancies generation, sensitizers, carbonaceous materials, and heterostructures with other materials.

- Defect control: It was found that defects on the surface/bulk of heteroanionic materials will act as recombination sites for photogenerated charge carriers. Therefore, decreasing these defects is necessary, but it is very challenging due to the crucial heavy anionization process. Also, it is required to investigate new precursors and synthesis procedures under moderate conditions to eliminate defects in the heteroanionic materials. Hence, defect control will help to reduce the recombination sites resulting in an improvement in the efficiency of the heteroanionic materials.

- Morphology control: The morphology of these photocatalysts is the most determining parameter in light absorption capability, charge-carrier transport, and surface reaction rates. Hence, various nanotechnology approaches can be extensively used to control the morphology characteristics of heteroanionic materials. Reducing the particle size to the nanoscale reduces the migration distance, which makes more electron–hole pairs to travel onto the catalyst surface before recombination. A hierarchical structure will improve the water-splitting process of heteroanionic photocatalysts.

In conclusion, heteroanionic materials have greatly improved over the past decade due to extensive research and development efforts. Due to the synergetic effect of light harvesting, electron–hole separation and migration, and surface reaction during the photocatalysis activity, more future research needs to be focused on making materials with all characteristics. Constant efforts in this field are anticipated to result in photocatalysts capable of splitting water and degrading contaminants with high efficiency. In addition, the knowledge gained via investigating these compounds will illuminate the future creation of novel, efficient, and sustainable heteroanionic photocatalysts. For the advancement of the catalysis process, a unified set of assessment standards and parameters for the overall efficiency of photocatalysts, including their performance and stability, are necessary. It will help the research community reach its long-term, sustainable solar-fuel generation goal.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/catal13010173

References

- Roy, A.; Sharma, A.; Yadav, S.; Jule, L.T.; Krishnaraj, R. Nanomaterials for Remediation of Environmental Pollutants. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2021, 2021, 1764647.

- Fang, B.; Xing, Z.; Sun, D.; Li, Z.; Zhou, W. Hollow semiconductor photocatalysts for solar energy conversion. Adv. Powder Mater. 2021, 1, 100021.

- Yan, T.; Yang, Q.; Feng, R.; Ren, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, M.; Yan, L.; Wei, Q. Highly effective visible-photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and simultaneous organic pollutant degradation over an urchin-like oxygen-doped MoS2/ZnIn2S4 composite. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16, 131.

- Subramanian, Y.; Mishra, B.; Mishra, R.P.; Kumar, N.; Bastia, S.; Anwar, S.; Gubendiran, R.; Chaudhary, Y.S. Efficient degradation of endocrine-disrupting compounds by heterostructured perovskite photocatalysts and its correlation with their ferroelectricity. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 11851–11861.

- Subramanian, Y.; Mishra, B.; Mandal, S.; Gubendiran, R.; Chaudhary, Y.S. Design of heterostructured perovskites for enhanced photocatalytic activity: Insight into their charge carrier dynamics. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 35, 179–185.

- Babel, S.; Sekartaji, P.A.; Sudrajat, H. ZnO nanoparticles for photodegradation of humic acid in water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 31163–31173.

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38.

- Kubiak, A.; Siwińska-Ciesielczyk, K.; Bielan, Z.; Zielińska-Jurek, A.; Jesionowski, T. Synthesis of highly crystalline photocatalysts based on TiO2 and ZnO for the degradation of organic impurities under visible-light irradiation. Adsorption 2019, 25, 309–325.

- Etacheri, V.; Di Valentin, C.; Schneider, J.; Bahnemann, D.; Pillai, S.C. Visible-light activation of TiO2 photocatalysts: Advances in theory and experiments. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2015, 25, 1–29.

- Chaudhary, Y.S.; Woolerton, T.W.; Allen, C.S.; Warner, J.H.; Pierce, E.; Ragsdale, S.W.; Armstrong, F.A. Visible light-driven CO2reduction by enzyme coupled CdS nanocrystals. Chem. Commun. 2011, 48, 58–60.

- Repo, E.; Rengaraj, S.; Pulkka, S.; Castangnoli, E.; Suihkonen, S.; Sopanen, M.; Sillanpää, M. Photocatalytic degradation of dyes by CdS microspheres under near UV and blue LED radiation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 120, 206–214.

- Singh, S.; Garg, S.; Saran, A.D. Photocatalytic activity of CdS and CdSe quantum dots for degradation of 3-aminopyridine. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2021, 6, 65.

- Toe, C.Y.; Scott, J.; Amal, R.; Ng, Y.H. Recent advances in suppressing the photocorrosion of cuprous oxide for photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical energy conversion. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2018, 40, 191–211.

- Chatterjee, K.; Skrabalak, S.E. Durable Metal Heteroanionic Photocatalysts. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 36670–36678.

- Yaghoubi-Berijani, M.; Bahramian, B. Synthesis, and New Design into Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Porphyrin Immobilization on the Surface of Bismuth Oxyhalides Modified with Polyaniline. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 4637–4654.

- Wang, Q.; Nakabayashi, M.; Hisatomi, T.; Sun, S.; Akiyama, S.; Wang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Xiao, X.; Watanabe, T.; Yamada, T.; et al. Oxysulfide photocatalyst for visible-light-driven overall water splitting. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 827–832.

- Takata, T.; Pan, C.; Domen, K. Recent progress in oxynitride photocatalysts for visible-light-driven water splitting. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2015, 16, 033506.

- Kageyama, H.; Hayashi, K.; Maeda, K.; Attfield, J.P.; Hiroi, Z.; Rondinelli, J.M.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. Expanding frontiers in materials chemistry and physics with multiple anions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 772.

- Zhang, B.; Xiao, J.; Jiao, S.; Zhu, H. Thermodynamic and thermoelectric properties of titanium oxycarbide with metal vacancy. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2022, 29, 787–795.

- Cuan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, T.; Liang, G.; Li, S.; Yu, X.; Pang, W.K.; Guo, Z. Multiple Anionic Transition-Metal Oxycarbide for Better Lithium Storage and Facilitated Multielectron Reactions. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 11665–11675.

- Fu, J.; Skrabalak, S.E. Enhanced Photoactivity from Single-Crystalline SrTaO2 N Nanoplates Synthesized by Topotactic Nitridation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 14169–14173.

- Kato, D.; Hongo, K.; Maezono, R.; Higashi, M.; Kunioku, H.; Yabuuchi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Okajima, H.; Zhong, C.; Nakano, K.; et al. Valence Band Engineering of Layered Bismuth Oxyhalides toward Stable Visible-Light Water Splitting: Madelung Site Potential Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18725–18731.

- Zhang, J.; Tian, B.; Wang, L.; Xing, M.; Lei, J. Mechanism of Photocatalysis. In Photocatalysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 11, pp. 1–15.

- Saravanan, R.; Gracia, F.; Stephen, A. Basic Principles, Mechanism, and Challenges of Photocatalysis. In Nanocomposites for Visible Light-Induced Photocatalysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 19–40.

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 Photocatalysis: Mechanisms and Materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986.

- Guo, S.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wei, B. Boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production from water by photothermally induced biphase systems. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1343.

- Rodenberg, A.; Orazietti, M.; Probst, B.; Bachmann, C.; Alberto, R.; Baldridge, K.K.; Hamm, P. Mechanism of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation by a Polypyridyl-Based Cobalt Catalyst in Aqueous Solution. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 54, 646–657.

- Reza, M.S.; Ahmad, N.B.H.; Afroze, S.; Taweekun, J.; Sharifpur, M.; Azad, A.K. Hydrogen Production from Water Splitting through Photocatalytic Activity of Carbon-Based Materials. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2022, 0930-7516.

- Subramanian, Y.; Ramasamy, V.; Karthikeyan, R.; Srinivasan, G.R.; Arulmozhi, D.; Gubendiran, R.K.; Sriramalu, M. Investigations on the enhanced dye degradation activity of heterogeneous BiFeO3–GdFeO3 nanocomposite photocatalyst. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01831.

- Subramanian, Y.; Ramasamy, V.; Gubendiran, R.K.; Srinivasan, G.R.; Arulmozhi, D. Structural, Optical, Thermal and Photocatalytic Dye Degradation Properties of BiFeO3–WO3 Nanocomposites. J. Electron. Mater. 2018, 47, 7212–7223.

- Kuriki, R.; Ichibha, T.; Hongo, K.; Lu, D.; Maezono, R.; Kageyama, H.; Ishitani, O.; Oka, K.; Maeda, K. A Stable, Narrow-Gap Oxyfluoride Photocatalyst for Visible-Light Hydrogen Evolution and Carbon Dioxide Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6648–6655.

- Ogawa, K.; Nakada, A.; Suzuki, H.; Tomita, O.; Higashi, M.; Saeki, A.; Kageyama, H.; Abe, R. Flux Synthesis of Layered Oxyhalide Bi4NbO8Cl Photocatalyst for Efficient Z-Scheme Water Splitting Under Visible Light. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 11, 5642–5650.

- Edalati, P.; Shen, X.-F.; Watanabe, M.; Ishihara, T.; Arita, M.; Fuji, M.; Edalati, K. High-entropy oxynitride as a low-bandgap and stable photocatalyst for hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 15076–15086.

- Maeda, K.; Domen, K. Oxynitride materials for solar water splitting. MRS Bull. 2011, 36, 25–31.

- Vonrüti, N.; Aschauer, U. Band-gap engineering in AB(OxS1−x)3 perovskite oxysulfides: A route to strongly polar materials for photocatalytic water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 15741–15748.

- Haman, Z.; Khossossi, N.; Kibbou, M.; Bouziani, I.; Singh, D.; Essaoudi, I.; Ainane, A.; Ahuja, R. Janus Aluminum Oxysulfide Al2OS: A promising 2D direct semiconductor photocatalyst with strong visible light harvesting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 589, 152997.

- Fuertes, A. Synthetic approaches in oxynitride chemistry. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2018, 51, 63–70.

- Ahmed, M.; Xinxin, G. A review of metal oxynitrides for photocatalysis. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 578–590.

- Ebbinghaus, S.G.; Abicht, H.-P.; Dronskowski, R.; Müller, T.; Reller, A.; Weidenkaff, A. Perovskite-related oxynitrides—Recent developments in synthesis, characterisation and investigations of physical properties. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2009, 37, 173–205.

- Fuertes, A. Chemistry and applications of oxynitride perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 3293–3299.

- Moriya, Y.; Takata, T.; Domen, K. Recent progress in the development of (oxy)nitride photocatalysts for water splitting under visible-light irradiation. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 1957–1969.

- Miyoshi, A.; Maeda, K. Recent Progress in Mixed-Anion Materials for Solar Fuel Production. Sol. RRL 2020, 5, 2000521.

- Higashi, M.; Abe, R.; Ishikawa, A.; Takata, T.; Ohtani, B.; Domen, K. Z-scheme Overall Water Splitting on Modified-TaON Photocatalysts under Visible Light (λ < 500 nm). Chem. Lett. 2008, 37, 138–139.

- Chun, W.-J.; Ishikawa, A.; Fujisawa, H.; Takata, T.; Kondo, J.N.; Hara, M.; Kawai, M.; Matsumoto, A.Y.; Domen, K. Conduction and Valence Band Positions of Ta2O5, TaON, and Ta3N5 by UPS and Electrochemical Methods. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 1798–1803.

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Gong, J. Tantalum-based semiconductors for solar water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 4395–4422.

- Tessier, F.; Marchand, R. Ternary and higher order rare-earth nitride materials: Synthesis and characterization of ionic-covalent oxynitride powders. J. Solid State Chem. 2003, 171, 143–151.

- Hellwig, A.; Hendry, A. Formation of barium-tantalum oxynitrides. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 4686–4693.

- Clarke, S.J.; Guinot, B.P.; Michie, C.W.; Calmont, M.J.C.; Rosseinsky, M.J. Oxynitride Perovskites: Synthesis and Structures of LaZrO2N, NdTiO2N, and LaTiO2N and Comparison with Oxide Perovskites. Chem. Mater. 2001, 14, 288–294.

- Yang, M.; Rodgers, J.A.; Middler, L.C.; Oró-Solé, J.; Jorge, A.B.; Fuertes, A.; Attfield, J.P. Direct Solid-State Synthesis at High Pressures of New Mixed-Metal Oxynitrides: RZrO2N (R = Pr, Nd, and Sm). Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 11498–11500.

- Kim, Y.-I.; Si, W.; Woodward, P.M.; Sutter, E.; Park, A.S.; Vogt, T. Epitaxial Thin-Film Deposition and Dielectric Properties of the Perovskite Oxynitride BaTaO2N. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 618–623.

- Le Paven-Thivet, C.; Ishikawa, A.; Ziani, A.; Le Gendre, L.; Yoshida, M.; Kubota, J.; Tessier, F.; Domen, K. Photoelectrochemical Properties of Crystalline Perovskite Lanthanum Titanium Oxynitride Films under Visible Light. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 6156–6162.

- Murphy, A.; Barnes, P.; Randeniya, L.; Plumb, I.; Grey, I.; Horne, M.; Glasscock, J.A. Efficiency of solar water splitting using semiconductor electrodes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 1999–2017.

- Hara, M.; Hitoki, G.; Takata, T.; Kondo, J.N.; Kobayashi, H.; Domen, K. TaON and Ta3N5 as new visible light driven photocatalysts. Catal. Today 2003, 78, 555–560.

- Takata, T.; Pan, C.; Domen, K. Design and Development of Oxynitride Photocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting under Visible Light Irradiation. Chemelectrochem 2015, 3, 31–37.

- Hara, M.; Chiba, E.; Ishikawa, A.; Takata, T.; Kondo, A.J.N.; Domen, K. Ta3N5 and TaON Thin Films on Ta Foil: Surface Composition and Stability. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 13441–13445.

- Maegli, A.E.; Otal, E.H.; Hisatomi, T.; Yoon, S.; Leroy, C.M.; Schäuble, N.; Lu, Y.; Grätzel, M.; Weidenkaff, A. Perovskite-Type LaTiO2N Oxynitrides for Solar Water Splitting: Influence of the Synthesis Conditions. Energy Procedia 2012, 22, 61–66.

- Rachel, A.; Ebbinghaus, S.; Güngerich, M.; Klar, P.; Hanss, J.; Weidenkaff, A.; Reller, A. Tantalum and niobium perovskite oxynitrides: Synthesis and analysis of the thermal behaviour. Thermochim. Acta 2005, 438, 134–143.

- Xu, J.; Pan, C.; Takata, T.; Domen, K. Photocatalytic overall water splitting on the perovskite-type transition metal oxynitride CaTaO2N under visible light irradiation. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 7191–7194.

- Cheng, H.; Huang, B.; Dai, Y. Engineering BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) nanostructures for highly efficient photocatalytic applications. Nanoscale 2013, 6, 2009–2026.

- Gordon, M.N.; Chatterjee, K.; Lambright, A.L.; Bueno, S.L.A.; Skrabalak, S.E. Organohalide Precursors for the Continuous Production of Photocatalytic Bismuth Oxyhalide Nanoplates. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 60, 4218–4225.

- Huang, W.L.; Zhu, Q. Electronic structures of relaxed BiOX (X = F, Cl, Br, I) photocatalysts. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 1101–1108.

- Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, L. Bismuth oxyhalide nanomaterials: Layered structures meet photocatalysis. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 8473–8488.

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y. Synthesis and internal electric field dependent photoreactivity of Bi3O4Cl single-crystalline nanosheets with high facet exposure percentages. Nanoscale 2013, 6, 167–171.

- Lou, Z.; Wang, P.; Huang, B.; Dai, Y.; Qin, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Enhancing Charge Separation in Photocatalysts with Internal Polar Electric Fields. Chemphotochem 2017, 1, 136–147.

- Li, M.; Huang, H.; Yu, S.; Tian, N.; Zhang, Y. Facet, Junction and Electric Field Engineering of Bismuth-Based Materials for Photocatalysis. Chemcatchem 2018, 10, 4477–4496.

- Sakthivel, T.; Venugopal, G.; Durairaj, A.; Vasanthkumar, S.; Huang, X. Utilization of the internal electric field in semiconductor photocatalysis: A short review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 72, 18–30.

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lai, C.; Zeng, G.; Huang, D.; Cheng, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, F.; Zhou, C.; Xiong, W. BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) photocatalytic nanomaterials: Applications for fuels and environmental management. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 254, 76–93.

- Ye, L.; Tian, L.; Peng, T.; Zan, L. Synthesis of highly symmetrical BiOI single-crystal nanosheets and their facet-dependent photoactivity. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 12479–12484.

- Tu, X.; Luo, S.; Chen, G.; Li, J. One-Pot Synthesis, Characterization, and Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of a BiOBr-Graphene Composite. Chem. A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 14359–14366.

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Ren, K.; Luo, H.; Peng, Y.; Li, G.; Yu, X. A novel nanoreactor framework of iodine-incorporated BiOCl core–shell structure: Enhanced light-harvesting system for photocatalysis. CrystEngComm 2011, 14, 700–707.

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, F. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Removal of NO in Air over BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) Single-Crystal Nanoplates Prepared at Room Temperature. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 6740–6746.

- Ma, Z.; Li, P.; Ye, L.; Zhou, Y.; Su, F.; Ding, C.; Xie, H.; Bai, Y.; Wong, P.K. Oxygen vacancies induced exciton dissociation of flexible BiOCl nanosheets for effective photocatalytic CO2 conversion. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 24995–25004.

- Kong, X.Y.; Lee, W.P.C.; Ong, W.-J.; Chai, S.-P.; Mohamed, A.R. Oxygen-Deficient BiOBr as a Highly Stable Photocatalyst for Efficient CO2Reduction into Renewable Carbon-Neutral Fuels. Chemcatchem 2016, 8, 3074–3081.

- Li, K.-L.; Lee, W.W.; Lu, C.-S.; Dai, Y.-M.; Chou, S.-Y.; Chen, H.-L.; Lin, H.-P.; Chen, C.-C. Synthesis of BiOBr, Bi3O4Br, and Bi12O17Br2 by controlled hydrothermal method and their photocatalytic properties. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 2688–2697.

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, W.-D. Facile synthesis of nanostructured BiOI microspheres with high visible light-induced photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 5866–5870.

- Henle, J.; Simon, P.; Frenzel, A.; Scholz, S.; Kaskel, S. Nanosized BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) Particles Synthesized in Reverse Microemulsions. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 366–373.

- Cheng, H.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; Ling, Y.; Dong, L.; Zha, J.; Yu, M.; Zhu, Z. Controllable design of bismuth oxyiodides by in-situ self-template phase transformation and heterostructure construction for photocatalytic removal of gas-phase mercury. Mater. Res. Bull. 2020, 131, 110968.

- Lu, L.; Kong, L.; Jiang, Z.; Lai, H.H.-C.; Xiao, T.; Edwards, P.P. Visible-Light-Driven Photodegradation of Rhodamine B on Ag-Modified BiOBr. Catal. Lett. 2012, 142, 771–778.

- Li, G.; Qin, F.; Yang, H.; Lu, Z.; Sun, H.; Chen, R. Facile Microwave Synthesis of 3D Flowerlike BiOBr Nanostructures and Their Excellent Cr VI Removal Capacity. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2012, 2508–2513.

- Sharma, I.; Tripathi, G.K.; Sharma, V.K.; Tripathi, S.N.; Kurchania, R.; Kant, C.; Sharma, A.K.; Saini, K. One-pot synthesis of three bismuth oxyhalides (BiOCl, BiOBr, BiOI) and their photocatalytic properties in three different exposure conditions. Cogent Chem. 2015, 1, 1076371.

- Cui, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xing, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, R. Bismuth oxychloride hollow microspheres with high visible light photocatalytic activity. Nano Res. 2016, 9, 593–601.

- Cui, J.; Tao, S.; Yang, X.; Yu, X.; Sun, S.; Yang, Q.; Wei, W.; Liang, S. Facile construction of nickel-doped hierarchical BiOCl architectures for enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activities. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 138, 111208.

- Yu, H.; Han, Q. Effect of reaction mediums on photocatalytic performance of BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I). Opt. Mater. 2021, 119, 111399.

- Lee, G.-J.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Wu, J.J. Fabrication of hierarchical bismuth oxyhalides (BiOX, X = Cl, Br, I) materials and application of photocatalytic hydrogen production from water splitting. Catal. Today 2018, 307, 197–204.

- Ye, L.; Jin, X.; Liu, C.; Ding, C.; Xie, H.; Chu, K.H.; Wong, P.K. Thickness-ultrathin and bismuth-rich strategies for BiOBr to enhance photoreduction of CO2 into solar fuels. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2016, 187, 281–290.

- Lan, M.; Zheng, N.; Dong, X.; Hua, C.; Ma, H.; Zhang, X. Bismuth-rich bismuth oxyiodide microspheres with abundant oxy-gen vacancies as an efficient photocatalyst for nitrogen fixation. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 9123–9129.

- Nishioka, S.; Kanazawa, T.; Shibata, K.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Loye, H.-C.Z.; Maeda, K. A zinc-based oxysulfide photocatalyst SrZn2S2O capable of reducing and oxidizing water. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 15778–15781.

- Zhang, G.; Wang, X. Oxysulfide Semiconductors for Photocatalytic Overall Water Splitting with Visible Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15580–15582.

- Pitha, J.J.; Smith, A.L.; Ward, R. The Preparation of Lanthanum Oxysulfide and its Properties as a Base Material for Phos-phors Stimulated by Infrared1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 1870–1871.

- Zachariasen, W.H. Crystal chemical studies of the 5f-series of elements. VII. The crystal structure of Ce2O2S, La2O2S and Pu2O2S. Acta Crystallogr. 1949, 2, 60–62.

- Wolff, C.M.; Frischmann, P.D.; Schulze, M.; Bohn, B.J.; Wein, R.; Livadas, P.; Carlson, M.T.; Jäckel, F.; Feldmann, J.; Würthner, F.; et al. All-in-one visible-light-driven water splitting by combining nanoparticulate and molecular co-catalysts on CdS nanorods. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 862–869.

- Ishikawa, A.; Takata, T.; Matsumura, T.; Kondo, J.N.; Hara, M.; Kobayashi, A.H.; Domen, K. Oxysulfides Ln2Ti2S2O5 as Stable Photocatalysts for Water Oxidation and Reduction under Visible-Light Irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 2637–2642.

- Abdullah, H.; Gultom, N.S.; Kuo, D.-H. Indium oxysulfide nanosheet photocatalyst for the hexavalent chromium detoxification and hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 6249–6264.

- Ogisu, K.; Ishikawa, A.; Teramura, K.; Toda, K.; Hara, M.; Domen, K. Lanthanum–Indium Oxysulfide as a Visible Light Driven Photocatalyst for Water Splitting. Chem. Lett. 2007, 36, 854–855.

- Zhang, F.; Maeda, K.; Takata, T.; Domen, K. Modification of oxysulfides with two nanoparticulate cocatalysts to achieve enhanced hydrogen production from water with visible light. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7313–7315.

- Lopes, D.; Daniel-Da-Silva, A.L.; Sarabando, A.R.; Arias-Serrano, B.I.; Rodríguez-Aguado, E.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Trindade, T.; Frade, J.R.; Kovalevsky, A.V. Design of Multifunctional Titania-Based Photocatalysts by Controlled Redox Reactions. Materials 2020, 13, 758.

- Hayami, W.; Tang, S.; Chiu, T.-W.; Tang, J. Reduction in Work Functions of Transition-Metal Carbides and Oxycarbides upon Oxidation. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 14559–14565.

- He, C.; Zheng, C.; Dai, W.; Fujita, T.; Zhao, J.; Ma, S.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Yang, J.; Wei, Z. Purification and Phase Evolution Mechanism of Titanium Oxycarbide (TiCxOy) Produced by the Thermal Reduction of Ilmenite. Minerals 2021, 11, 104.

- Calvillo, L.; García, G.; Paduano, A.; Guillen-Villafuerte, O.; Valero-Vidal, C.; Vittadini, A.; Bellini, M.; Lavacchi, A.; Agnoli, S.; Martucci, A.; et al. Electrochemical Behavior of TiOxCy as Catalyst Support for Direct Ethanol Fuel Cells at Intermediate Temperature: From Planar Systems to Powders. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 8, 716–725.

- Antolini, E.; Gonzalez, E.R. Tungsten-based materials for fuel cell applications. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 96, 245–266.

- Maeda, K.; Takata, T.; Domen, K. (Oxy)nitrides and Oxysulfides as Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting. In Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Through Nanotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 487–529.

- Castillo-Cabrera, G.X.; Espinoza-Montero, P.J.; Alulema-Pullupaxi, P.; Mora, J.R.; Villacís-García, M.H. Bismuth Oxyhalide-Based Materials (BiOX: X = Cl, Br, I) and Their Application in Photoelectrocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants in Water: A Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 900622.

- Suresh, R.; Rajendran, S.; Kumar, P.S.; Hoang, T.K.; Soto-Moscoso, M. Halides and oxyhalides-based photocatalysts for abatement of organic water contaminants—An overview. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113149.

- Nava-Núñez, M.Y.; Jimenez-Relinque, E.; la Cruz, A.M.-D.; Castellote, M. Photocatalytic NOx Removal in Bismuth-Oxyhalide (BiOX, X = I, Cl) Cement-Based Materials Exposed to Outdoor Conditions. Catalysts 2022, 12, 982.

- Talreja, N.; Afreen, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Chauhan, D.; Mera, A.C.; Rodríguez, C.; Mangalaraja, R. Bimetal (Fe/Zn) doped BiOI photocatalyst: An effective photodegradation of tetracycline and bacteria. Chemosphere 2021, 280, 130803.

- Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Song, L. A novel F-doped BiOCl photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic performance. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 173, 298–308.

- Mohan, H.; Yoo, S.; Thimmarayan, S.; Oh, H.S.; Kim, G.; Seralathan, K.-K.; Shin, T. Nickel decorated manganese oxynitride over graphene nanosheets as highly efficient visible light driven photocatalysts for acetylsalicylic acid degradation. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 289, 117864.

- Cosham, S.D.; Celorrio, V.; Kulak, A.N.; Hyett, G. Observation of visible light activated photocatalytic degradation of stearic acid on thin films of tantalum oxynitride synthesized by aerosol assisted chemical vapour deposition. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 10619–10627.

- Di, J.; Xia, J.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Dai, S. Bismuth oxyhalide layered materials for energy and environmental applications. Nano Energy 2017, 41, 172–192.

- Tang, X.-D.; Ye, H.-Q.; Hu, H.-X. Sulfurization synthesis and photocatalytic activity of oxysulfide La3NbS2O5. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 2644–2649.