Gesneriaceae is a pantropical family of plants that, thanks to their lithophytic and epiphytic growth forms, have developed different strategies for overcoming water scarcity. Desiccation tolerance or “resurrection” ability is one of them. This characteristic relies on the plant’s ability to withstand very low water contents in their tissues (~10% relative water content (RWC)) and fully recover upon re-watering, a very rare phenomenon among angiosperms, with less than 0.1% of them being desiccation-tolerant (DT). Physiological responses of desiccation tolerance are also activated during freezing temperatures, a stress that many of the resurrection gesneriads suffer due to their mountainous habitat. Research on desiccation- and freezing-tolerant gesneriads is a great opportunity for crop improvement, and some of them have become reference resurrection angiosperms for study (Dorcoceras hygrometrica, Haberlea rhodopensis and Ramonda myconi).

- resurrection species

- desiccation tolerance

- freezing stress

- Gesneriaceae

- oxidative damage

- photooxidative damage

- structural damage

1. Drought-induced desiccation

1.1. Desiccation Tolerance Strategies among Gesneriads

Desiccation tolerance has been described in at least nine Gesneriaceae genera, implying that this is the angiosperm family with the largest number of DT genera. Nowadays, the Gesneriaceae family contains three subfamilies: Sanangoideae, Gesnerioideae, and Didymocarpoideae. All documented DT gesneriads are members of the Trichosporeae tribe from Didymocarpoideae[1].

So far, mechanisms have been characterized among a significant number of studies, and in fact two gesneriads (Dorcoceras hyrgrometricum and Haberlea rhodopensis) are among the top five most studied resurrection angiosperms[2]. Both species, together with Ramonda serbica and, to a lesser extent, others such as Paraboea rufencens, Paraboea crassifolia, Oreocharis mileensis, Ramonda myconi, and Ramonda nathaliae, have allowed researchers to unravel the mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in gesneriads[3][4][5][6][7]. Even thought more studies are needed, currently available information suggests that most resurrection gesneriads share similar protective mechanisms, with minor species-specific differences[8].

In response to desiccation, all resurrection gesneriads utilize a strategy known as homoiochlorophylly; that is, they retain chlorophyll (Chl) in the desiccated state. The opposite strategy, shown by some monocots, is poikilochlorophylly, which involves a complete degradation of the photosynthetic apparatus. However, in gesneriads, Chl retention is not always complete; for example, it has been reported to decrease by 20 to 70% in the desiccated state in Ramonda species[9].

The rate of CO2 assimilation is remarkably low in R. myconi, and it decreases concomitantly with the loss of water content in H. rhodopensis. This process is first due to stomatal closure, and afterwards to reduced photochemical activity[6][10]. In parallel, there is a shift between linear electron flow (LEF) and cyclic electron flow (CEF), which may contribute to the absence of a drastic decreases in the NADP/NADPH ratio, although a slight increase in NADPH could be observed at 38% of water content[11]. Once rehydration starts, the activity of PSI is more rapidly recovered than that of PSII[10]. These observations suggest that the partial loss of Chl does not indicate the occurrence of damage in the photosynthetic apparatus. Furthermore, given that Chl molecules are a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) when photosynthesis is impeded, partial Chl degradation represents the activation of a photoprotective mechanism[12]. As a consequence of the potential ROS generation within the photosynthetic apparatus, oxidative stress is one of the main challenges associated with the process of desiccation and subsequent rehydration[13].

1.2. Avoiding Reactive Oxygen Species Formation

To counteract ROS production, resurrection gesneriads constitutively express large pools of antioxidant molecules, including ascorbate and glutathione[7][14]. Other low-molecular-weight antioxidants are phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, polyphenols), whose biosynthetic route (Shikimate pathway) is overexpressed during desiccation in H. rhodopensis[15]. A similar polyphenol composition has been described in all gesneriad species studied so far: H. rhodopensis, R. myconi, R. serbica, and D. hygrometricum[16][17][18]. Thus, Georgieva et al. proposed that the high polyphenol content is a characteristic feature of gesneriads[19].

The activity of all of these antioxidants is complemented by the action of antioxidant enzymes. For example, Gechev et al. found more genes in H. rhodopensis encoding superoxide dismutases, monodehydroascorbate reductases (MDHARs), and glutathione reductases than in most plant species with sequenced genomes, which gives a hint about its constitutive tolerance against desiccation[20]. Mladenov et al. also reported on the accumulation of ascorbate peroxidase and glutathione peroxidase in response to desiccation, as was shown in R. nathalie. The antioxidant machinery that accumulates during desiccation is also maintained in the desiccated state to be used during the first stages of subsequent rehydration[7][21].

One of the main targets of ROS are polyunsaturated fatty acids, whose oxidation gives rise to the formation of lipid peroxides that propagate in membranes through peroxidation chains. Paradoxically, polyunsaturated fatty acids enhance membrane fluidity in desiccated tissues. This is probably why the response of the unsaturation ratio varies so widely among the gesneriads studied: in H. rhodopensis, it was not affected by desiccation, while it increased in Boea hygroscopica and decreased in R. serbica[22][23][24]. The main antioxidant involved in avoiding the propagation of such peroxidation chains is tocopherol, and in fact the enhancement of this antioxidant in response to desiccation is a general trait observed in most (if not all) DT plants, including gesneriads such as D. hygrometricum, R. myconi, and H. rhodopensis[6][13][23][25].

The production of ROS within the photosynthetic apparatus can be prevented by simply reducing light absorption within the photosystem antennae. To reduce photon absorption by Chl, H. rhodopensis constitutively expresses high levels of red anthocyanins in the abaxial side of the leaves[26]. When the leaves curl, the anthocyanic layer becomes exposed to light, causing a decrease in light reaching the mesophyll. Another strategy to reduce ROS formation is to enhance the dissipation of energy absorbed by Chl as heat, the so-called non-photochemical quenching (NPQ). This mechanism is linked to the accumulation of certain proteins, such as PsbS, and the presence of zeaxanthin[27]. PsbS is specifically induced by desiccation in H. rhodopensis, while zeaxanthin has been shown to be synthesized in response to desiccation in R. myconi[6][28].

1.3. Avoiding Structural Damage

A second challenge linked to desiccation is mechanical/structural damage caused by cell shrinkage, which is an obvious consequence of desiccation and leaf curling. First of all, cell walls have to be flexible enough to allow correct folding and to follow such volume alterations[29]. Changes in cell wall permeability and plasticity have been reported in H. rhodopensis[30]. The plasticity of the cell wall mainly depends on the relationship between the cellulose-xyloglucan network and pectin polysaccharides, whereby changes in their composition and connection lead to changes in cell flexibility[21].Indeed, Mladenov et al. reported downregulated levels of genes involved in lignin and cellulose synthesis, and increased levels of enzymes involved in cell wall remodelling.

Maintaining membrane integrity is the main objective of desiccation tolerance strategies. This is accomplished by profound lipid remodelling, and membrane stabilization is further strengthened by the interaction with proteins, sugars, and remaining water molecules[13]. Consequently, degradation of lipids is a limited phenomenon among resurrection plants, and membranes are highly preserved. In chloroplasts of R. myconi, membrane stability is enhanced by a partial conversion of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) to digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), a bilayer-forming lipid[6]. Stability is reinforced in H. rhodopensis by the presence of a dense luminal substance (DLS), most likely a phenolic compound that prevents conformational changes of thylakoids[31]. Additionally, phospholipids, such as phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine, are degraded during desiccation and there is an increase in phospholipase D[15]. The accumulation of other lipids, such as sitosterol, is also a species-specific response to desiccation in H. rhodopensis[23].

In H. rhodopensis, the primary central vacuole disappears when the cell desiccates, and smaller secondary vacuoles emerge in the vicinity of the cell wall. At the same time, organelles take the place of the central primary vacuole[14]. The increase in the number of smaller vacuoles, which have a greater area/volume ratio, makes it possible to maintain the membrane surface area during the volume reduction caused by water loss[32]. Desiccated chloroplasts (termed desiccoplasts) adopt a rounded shape and they undergo an enhancement in the number and size of plastoglobules[14].

The accumulation of compatible solutes, acting as osmoprotectants, is a general response to water loss. In D. hygrometricum, R. myconi, and H. rhodopensis, sucrose is the main compound accumulated in response to desiccation[33]. Sucrose can be produced after starch degradation or can come from gluconeogenesis, as there is consumption of glycolytic intermediates directly related to the accumulation of sucrose[14][23]. In D. hygrometricum, raffinose-family compounds also increase during desiccation[8]. At the later stages of desiccation, the massive accumulation of sucrose is more directly related to membrane protection by preventing non-bilayer phase separation and membrane fusion[13]. Coincident with their protective functions, both sucrose and raffinose sharply decline after rehydration[14][23].

Once the water potential surpasses a certain threshold (−100 MPa), there is a process of vitrification and the cytoplasm reaches the so-called glassy state, an amorphous metastable state[13]. In this situation, most metabolic activities cease and chemical reactivity is inhibited. Transition to the glass state implies positive aspects for DT organisms, as the diffusion of oxygen is greatly reduced, decreasing ROS generation and preventing further water loss. Vitrification was studied in R. myconi by Fernández-Marín et al., who showed that this stage can occur in nature, as it can be reached in desiccated leaves at 20 °C[34].

1.4. Cellular Protection

Desiccation induces the expression of genes encoding several sets of protective proteins. This is the case of early light-induced proteins (ELIPs) and PsbS, which are involved in the maintenance of chloroplasts and the regulation of photosynthesis. Their expression is maintained during the rehydration process, and some of them are still present 7 days after the onset of rehydration. Desiccation also induces massive expression of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins in H. rhodopensis, R. serbica, and D. hygrometricum[20][21]. These proteins act as water replacement molecules to maintain the structure of the membranes and organelles, as they have little possibility of interacting with other molecules due to their low capacity for forming hydrogen bonds[35].

Damaged DNA is another key aspect of maintaining genome integrity. It can be repaired by several processes, including nucleotide excision repair, in which genes have been reported to be specifically activated during dehydration in H. rhodopensis. In case cellular damage occurs, autophagy is also an option[15]. By inducing autophagy, cell death can be inhibited in order to recycle damaged structures to create new structures needed for the protective response of the organism against water deficiency stress, as has been observed in D. hygrometricum[25]. The promotion of autophagy is in accordance with the decreasing transcription and protein accumulation of AMC4 in H. rhodopensis during desiccation, and works as a promoter of programmed cell death under stress[21][36]. This is how DT plants suppress senescence when dehydrated[13].

2. Freezing-Induced Desiccation

Cross-tolerance to freezing and desiccation is somewhat logical, since dehydration prevents the formation of ice crystals inside cells. In fact, it has been documented that H. rhodopensis has the ability to dehydrate rapidly under freezing temperatures[37]. Consequently, most responses are shared between drought-induced desiccation (DID) and freezing-induced desiccation (FID)[38]. However, there are slight differences between these two processes; for example, FID is characterized by faster recovery of PSII compared to DID[39]. In addition, during FID, secondary vacuoles are reported to appear at 60% RWC. This process is similar to the one that happens after DID, but it occurs more rapidly after FID, most likely because of the RWC recovery rate enabled by the environment and the influence of freezing[38].

In addition to FID, it has been documented in manipulative experiments that hydrated leaves of R. myconi freeze at a relatively high temperature (−2 °C). Tissue freezing involves an abrupt reduction of photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), which correlates with the enzymatic formation of zeaxanthin. Interestingly, the glass transition in hydrated leaves occurs at −15 °C, meaning that enzyme activity is possible in frozen leaves of R. myconi[34]. This justifies the induction of antioxidant enzymes in frozen leaves of H. rhodopensis[37]. Recovery of Fv/Fm is initially fast upon transfer to warm conditions and is completely restored in 6 h. This means that even in winter, R. myconi is photosynthetically active whenever the temperature is above the freezing point[6].

Apart from the obvious fact that desiccation protects the plant from ice formation, in order to fully withstand winter stress, resurrection gesneriads have to develop a profound metabolic reconfiguration through a process of seasonal acclimation. Only a few studies have addressed the specific mechanisms that H. rhodopensis and R. myconi employ to cope with low-temperature stress. These include substantial induction of thermal energy dissipation, which is in agreement with a high accumulation of zeaxanthin, and the PsbS protein[6][10]. Other stress proteins that accumulate in H. rhodopensis in response to low temperature are Lhcb5, Lhcb6, dehydrins, and ELIPs[38]. Genes encoding lipocalins are also upregulated[26]. Lipocalins are small ligand-binding proteins that can be found in both the cell and the chloroplast membrane. In winter, there is also a substantial accumulation of low-molecular-weight metabolites, such as polyphenols[37]; sugars, such as trehalose, maltose, raffinose, sucrose, and glucose; amino acids, such as proline, glycine, serine, alanine, asparagine, and aspartate; polyamines, such as putrescine and ornithine; and antioxidants of the glutathione-ascorbate system[6][26][28][37]. The joint action of all of these mechanisms decreases photosynthesis, lowers osmotic potential, and keep plants in a state primed for freezing protection[26].

3. Concluding Remarks

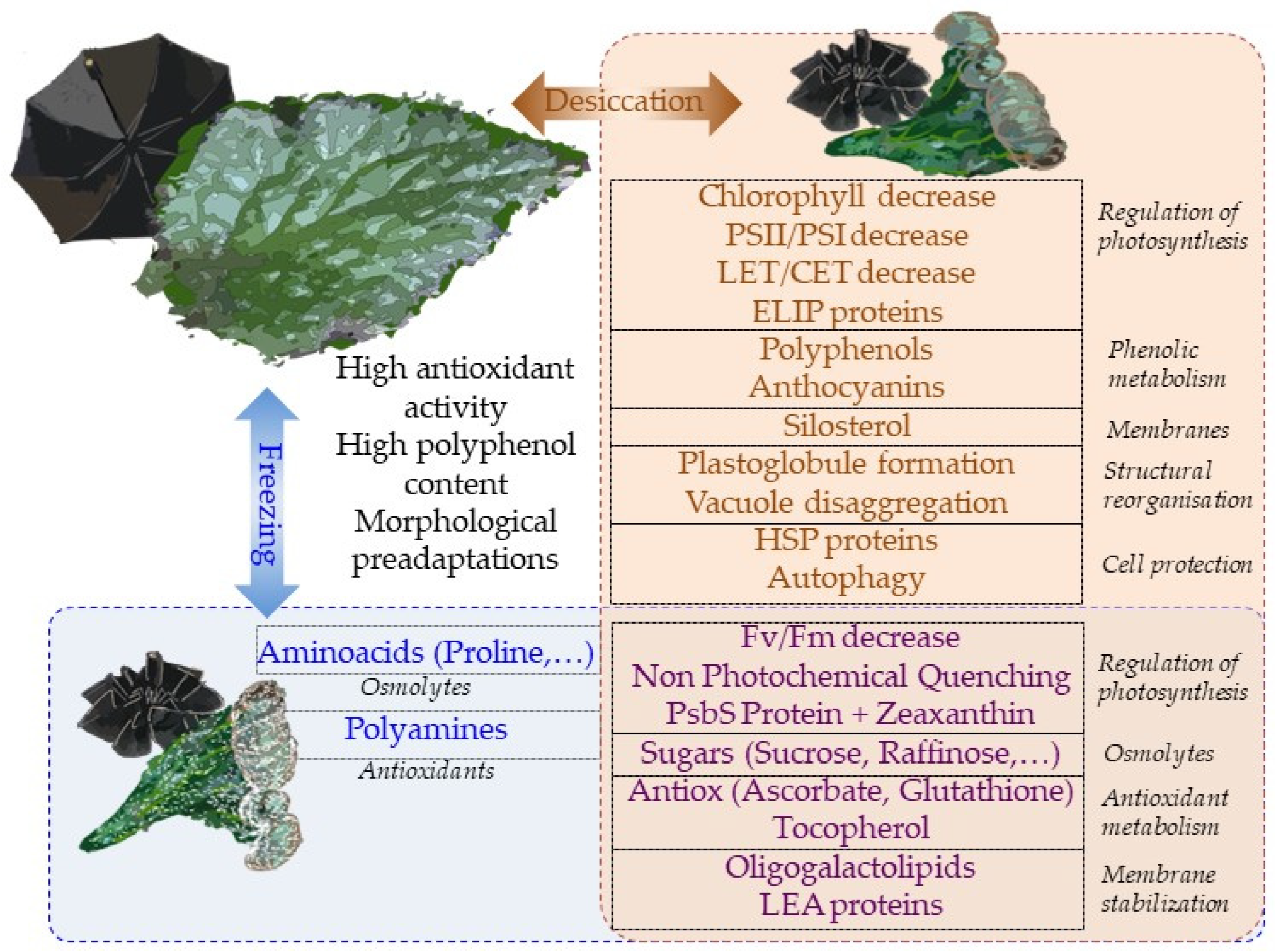

Overall, most physiological mechanisms are shared in terms of the responses to desiccation and low-temperature stresses (Figure 1). This is perhaps the reason why tertiary paleotropical relict gesneriads were able to survive in sheltered habitats of southern Europe during the quaternary glaciations. The question of whether freezing tolerance is a constitutive trait in resurrection gesneriads or evolved in temperate species as a result of climate cooling deserves further studies.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology12010107

References

- Gaff, D.F.; Oliver, M. The Evolution of Desiccation Tolerance in Angiosperm Plants: A Rare yet Common Phenomenon. Functional Plant Biology 2013, 40, 315–328, doi:10.1071/FP12321.

- Tebele, S.M.; Marks, R.A.; Farrant, J.M. Two Decades of Desiccation Biology: A Systematic Review of the Best Studied Angiosperm Resurrection Plants. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, doi:10.3390/PLANTS10122784.

- Huang, W.; Yang, S.J.; Zhang, S.B.; Zhang, J.L.; Cao, K.F. Cyclic Electron Flow Plays an Important Role in Photoprotection for the Resurrection Plant Paraboea Rufescens under Drought Stress. Planta 2012, 235, 819–828, doi:10.1007/S00425-011-1544-3/FIGURES/6.

- Shen, Y.; Tang, M.J.; Hu, Y.L.; Lin, Z.P. Isolation and Characterization of a Dehydrin-like Gene from Drought-Tolerant Boea Crassifolia. Plant Science 2004, 166, 1167–1175, doi:10.1016/J.PLANTSCI.2003.12.025.

- Li, A.; Wang, D.; Yu, B.; Yu, X.; Li, W. Maintenance or Collapse: Responses of Extraplastidic Membrane Lipid Composition to Desiccation in the Resurrection Plant Paraisometrum Mileense. PLoS One 2014, 9, e103430, doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0103430.

- Fernández-Marín, B.; Nadal, M.; Gago, J.; Fernie, A.R.; López-Pozo, M.; Artetxe, U.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Verhoeven, A. Born to Revive: Molecular and Physiological Mechanisms of Double Tolerance in a Paleotropical and Resurrection Plant. New Phytologist 2020, 226, 741–759, doi:10.1111/nph.16464.

- Jovanović, Ž.; Rakić, T.; Stevanović, B.; Radović, S. Characterization of Oxidative and Antioxidative Events during Dehydration and Rehydration of Resurrection Plant Ramonda Nathaliae. Plant Growth Regul 2011, 64, 231–240, doi:10.1007/s10725-011-9563-4.

- Liu, J.; Moyankova, D.; Djilianov, D.; Deng, X. Common and Specific Mechanisms of Desiccation Tolerance in Two Gesneriaceae Resurrection Plants. Multiomics Evidences. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01067.

- Drazic, G.; Mihailovic, N.; Stevanovic, B. Chlorophyll Metabolism in Leaves of Higher Poikilohydric Plants Ramonda Serbica Panč, and Ramonda Nathaliae Panč, et Petrov. during Dehydration and Rehydration. J Plant Physiol 1999, 154, 379–384, doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(99)80184-9.

- Georgieva, K.; Mihailova, G.; Velitchkova, M.; Popova, A. Recovery of Photosynthetic Activity of Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis from Drought-and Freezing-Induced Desiccation. Photosynthetica 2020, 58, 911–921, doi:10.32615/ps.2020.044.

- Mladenov, P.; Finazzi, G.; Bligny, R.; Moyankova, D.; Zasheva, D.; Boisson, A.M.; Brugière, S.; Krasteva, V.; Alipieva, K.; Simova, S.; et al. In Vivo Spectroscopy and NMR Metabolite Fingerprinting Approaches to Connect the Dynamics of Photosynthetic and Metabolic Phenotypes in Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis during Desiccation and Recovery. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6, 1–14, doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00564.

- Asada, K. Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Chloroplasts and Their Functions. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 391–396, doi:10.1104/PP.106.082040.

- Oliver, M.J.; Farrant, J.M.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Mundree, S.; Williams, B.; Bewley, J.D. Desiccation Tolerance: Avoiding Cellular Damage during Drying and Rehydration. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2020, 71, 435–460, doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-071219-105542.

- Georgieva, K.; Rapparini, F.; Bertazza, G.; Mihailova, G.; Sárvári; Solti; Keresztes Alterations in the Sugar Metabolism and in the Vacuolar System of Mesophyll Cells Contribute to the Desiccation Tolerance of Haberlea Rhodopensis Ecotypes. Protoplasma 2017, 254, 193–201, doi:10.1007/s00709-015-0932-0.

- Liu, J.; Moyankova, D.; Lin, C.T.; Mladenov, P.; Sun, R.Z.; Djilianov, D.; Deng, X. Transcriptome Reprogramming during Severe Dehydration Contributes to Physiological and Metabolic Changes in the Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis. BMC Plant Biol 2018, 18, doi:10.1186/s12870-018-1566-0.

- Cañigueral, S.; Salvía, M.J.; Vila, R.; Iglesias, J.; Virgili, A.; Parella, T. New Polyphenol Glycosides from Ramonda Myconi. J Nat Prod 1996, 59, 419–422, doi:10.1021/NP960204M.

- Jensen, S.R. Caffeoyl Phenylethanoid Glycosides in Sanango Racemosum and in the Gesneriaceae. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 777–783, doi:10.1016/0031-9422(96)00186-0.

- Feng, W.S.; Li, Y.J.; Zheng, X.K.; Wang, Y.Z.; Su, F.Y.; Pei, Y.Y. Two New C-Glycosylflavones from Boea Hygrometrica. J Asian Nat Prod Res 2011, 13, 618–623, doi:10.1080/10286020.2011.579903.

- Georgieva, K.; Dagnon, S.; Gesheva, E.; Bojilov, D.; Mihailova, G.; Doncheva, S. Antioxidant Defense during Desiccation of the Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2017, 114, 51–59, doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.02.021.

- Gechev, T.S.; Benina, M.; Obata, T.; Tohge, T.; Sujeeth, N.; Minkov, I.; Hille, J.; Temanni, M.R.; Marriott, A.S.; Bergström, E.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Desiccation Tolerance in the Resurrection Glacial Relic Haberlea Rhodopensis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2013, 70, 689–709, doi:10.1007/s00018-012-1155-6.

- Mladenov, P.V.; Zasheva, D.; Planchon, S.; Leclercq, C.; Falconet, D.; Moyet, L.; Brugière, S.; Moyankova, D.; Tchorbadjieva, M.; Ferro, M.; et al. Proteomics Evidence of a Systemic Response to Desiccation in the Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis. SSRN Electronic Journal 2022, 23, doi:10.2139/ssrn.4088645.

- Quartacci, M.F.; Glišić, O.; Stevanović, B.; Navari-Izzo, F. Plasma Membrane Lipids in the Resurrection Plant Ramonda Serbica Following Dehydration and Rehydration. J Exp Bot 2002, 53, 2159–2166, doi:10.1093/JXB/ERF076.

- Moyankova, D.; Mladenov, P.; Berkov, S.; Peshev, D.; Georgieva, D.; Djilianov, D. Metabolic Profiling of the Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis during Desiccation and Recovery. Physiol Plant 2014, 152, 675–687, doi:10.1111/ppl.12212.

- Navari‐Izzo, F.; Ricci, F.; Vazzana, C.; Quartacci, M.F. Unusual Composition of Thylakoid Membranes of the Resurrection Plant Boea Hygroscopica: Changes in Lipids upon Dehydration and Rehydration. Physiol Plant 1995, 94, 135–142, doi:10.1111/J.1399-3054.1995.TB00794.X.

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, B.; Phillips, J.; Zhang, Z.N.; Du, H.; Xu, T.; Huang, L.C.; Zhang, X.F.; Xu, G.H.; Li, W.L.; et al. Global Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Acclimation-Primed Processes Involved in the Acquisition of Desiccation Tolerance in Boea Hygrometrica. Plant Cell physiology 2015, 56, 1429–1441, doi:10.1093/PCP/PCV059.

- Benina, M.; Obata, T.; Mehterov, N.; Ivanov, I.; Petrov, V.; Toneva, V.; Fernie, A.R.; Gechev, T.S. Comparative Metabolic Profiling of Haberlea Rhodopensis, Thellungiella Halophyla, and Arabidopsis Thaliana Exposed to Low Temperature. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00499.

- Pinnola, A.; Bassi, R. Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Plant Photoprotection. Biochem Soc Trans 2018, 46, 467–482, doi:10.1042/BST20170307.

- Mihailova, G.; Vasileva, I.; Gigova, L.; Gesheva, E.; Simova-Stoilova, L.; Georgieva, K. Antioxidant Defense during Recovery of Resurrection. Plants 2022, 11, doi:doi.org/10.3390/plants 11020175.

- Mitra, J.; Xu, G.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Deng, X. Understanding Desiccation Tolerance Using the Resurrection Plant Boea Hygrometrica as a Model System. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4, doi:10.3389/FPLS.2013.00446/BIBTEX.

- Mihailova, G.; Kocheva, K.; Goltsev, V.; Kalaji, H.M.; Georgieva, K. Application of a Diffusion Model to Measure Ion Leakage of Resurrection Plant Leaves Undergoing Desiccation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 125, 185–192, doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.02.008.

- Georgieva, K.; Sárvári, É.; Keresztes, Á. Protection of Thylakoids against Combined Light and Drought by a Lumenal Substance in the Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis. Ann Bot 2010, 105, 117–126, doi:10.1093/AOB/MCP274.

- Farrant, J.M.; Cooper, K.; Nell, H. Desiccation Tolerance. In Plant Stress Physiology; 2000; pp. 248–265 ISBN 9781845939953.

- Muller, J.; Sprenger, N.; Bortlik, K.; Boiler, T.; Wiemken Muller, A.; Bortlik, N.; Wiemken, T.; Muller, J.; Sprenger, N.; Bortlik, K.; et al. Desiccation Increases Sucrose Levels in Ramonda and Haberlea, Two Genera of Resurrection Plants in the Gesneriaceae. Physiol Plant 1997, 100, 153–158, doi:10.1111/J.1399-3054.1997.TB03466.X.

- Fernández-Marín, B.; Neuner, G.; Kuprian, E.; Laza, J.M.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Verhoeven, A. First Evidence of Freezing Tolerance in a Resurrection Plant: Insights into Molecular Mobility and Zeaxanthin Synthesis in the Dark. Physiol Plant 2018, 163, 472–489, doi:10.1111/PPL.12694.

- Djilianov, D.; Ivanov, S.; Moyankova, D.; Miteva, L.; Kirova, E.; Alexieva, V.; Joudi, M.; Peshev, D.; van den Ende, W. Sugar Ratios, Glutathione Redox Status and Phenols in the Resurrection Species Haberlea Rhodopensis and the Closely Related Non-Resurrection Species Chirita Eberhardtii. Plant biology 2011, 13, 767–776, doi:10.1111/J.1438-8677.2010.00436.X.

- Petrov, V.; Hille, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. ROS-Mediated Abiotic Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6, doi:10.3389/FPLS.2015.00069/BIBTEX.

- Georgieva, K.; Mihailova, G.; Gigova, L.; Dagnon, S.; Simova-Stoilova, L.; Velitchkova, M. The Role of Antioxidant Defense in Freezing Tolerance of Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2021, 27, 1119–1133, doi:10.1007/s12298-021-00998-0.

- Mihailova, G.; Christov, N.K.; Sárvári, É.; Solti, Á.; Hembrom, R.; Solymosi, K.; Keresztes, Á.; Velitchkova, M.; Popova, A. v.; Simova-Stoilova, L.; et al. Reactivation of the Photosynthetic Apparatus of Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis during the Early Phase of Recovery from Drought- and Freezing-Induced Desiccation. Plants 2022, 11, doi:10.3390/plants11172185.

- Georgieva, K.; Popova, A. v.; Mihailova, G.; Ivanov, A.G.; Velitchkova, M. Limiting Steps and the Contribution of Alternative Electron Flow Pathways in the Recovery of the Photosynthetic Functions after Freezing-Induced Desiccation of Haberlea Rhodopensis. Photosynthetica 2022, 60, 136–146, doi:10.32615/ps.2022.008.

- Kuroki, S.; Tsenkova, R.; Moyankova, D.; Muncan, J.; Morita, H.; Atanassova, S.; Djilianov, D. Water Molecular Structure Underpins Extreme Desiccation Tolerance of the Resurrection Plant Haberlea Rhodopensis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39443-4.

- Ivanova, A.; O′Leary, B.; Signorelli, S.; Falconet, D.; Moyankova, D.; Whelan, J.; Djilianov, D.; Murcha, M.W. Mitochondrial Activity and Biogenesis during Resurrection of Haberlea Rhodopensis. New Phytologist 2022, doi:10.1111/nph.18396.