Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

A biofilm is an aggregation of surface-associated microbial cells that is confined in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix. Infections caused by microbes that form biofilms are linked to a variety of animals, including insects and humans. Antibiotics and other antimicrobials can be used to remove or eradicate biofilms in order to treat infections.

- biofilm

- biofilm infections

- drug resistance

- nanoparticles

1. Introduction

A biofilm comprises a collection of micro-organisms, primarily bacteria, but also fungi, viruses, protozoan, and other microbes. To ensure their survival, bacteria maintain an organized and structured growth and proliferation strategy on any surface. Antimicrobial chemicals, unfavorable temperature and pH conditions, and other environmental variables cause bacteria to assemble into biofilms as a stress response mechanism [1]. The organization of the bacteria in the biofilm, which takes the shape of microcolonies enclosed in the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) of the matrix, makes it possible for them to survive. By facilitating the movement of nutrients and water, controlling metabolism and tolerance to desiccation, providing resistance to antibiotics and disinfectants, with cell aggregation inducing coordination of virulence factor expression via QS and affecting predator–prey interactions, the EPS matrix holds the bacterial cells together and gives biofilms resilience and versatility [2][3][4][5].

Prior to the discovery of antibiotics, biofilm infections posed a serious risk to human health and were responsible for many illnesses and even fatalities. Numerous antibiotics have been developed since Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928, which are used to treat bacterial infections saving countless lives [6]. Nevertheless, because antibiotics are overused and misused, bacterial resistance and even multidrug resistance have emerged, signalling the start of the “post-antibiotic age” [7]. Many illnesses are exclusively induced by biofilm infections. Due to the novel resistance mechanisms evolved by biofilm infection, it has become a serious and long-term hazard to public health and the economy as a result of the high mortality rate it causes [8]. These infections are treated with a variety of new antibiotics; however, it has become clear that biofilm bacteria frequently exhibit enhanced antibiotic resistance due to the ineffectiveness of antibiotics against biofilm-associated infections [9]. Furthermore, recent research has revealed that the extracellular polymeric matrix (EPM) has little effect on antibiotic dispersion [10]. Another theory is that after adhering to polysaccharides, DNA, and proteins in the biofilm, antibiotics seem to be more biologically inactive or cannot reach the concentrations necessary for effective bacterial eradication. The challenges discussed above highlight the critical need for novel methods of inhibiting biofilm formation and removal. The creation of new antibiotics, however, continues to be far behind the emergence of bacterial resistance. To combat biofilm infections that are multidrug-resistant, new approaches are desperately needed [11].

The increase in bacterial resistance to antibiotics has prompted researchers to look into various antimicrobial therapeutic strategies that are utilized to create potent antibacterial agents. Transitioning from normal therapy towards high-tech solutions based on nanomaterials might be one of the possibly successful and unquestionable intriguing substance- or biofilm-fighting strategies. The unique properties of nanomaterials have revolutionized a variety of technologies and areas, including medicine. Nanomaterials, which can be tailored to have sizes comparable to biomolecules and bacterial intracellular structures, can be developed as innovative therapeutic approaches. Nanoparticles work by avoiding bacterial defences against drug resistance and preventing the growth of biofilms or other critical processes linked to a bacterium’s potential for antipathy. Nanoparticles have the ability to enter the cell wall and membrane of bacteria and disrupt vital molecular processes. Nanoparticles may exhibit synergy when used with the right antibiotics and aid in preventing the growing global bacterial resistance. Moreover, polymer-based nanoparticles enable the development of a variety of therapeutic goods due to properties like improved biocompatibility and biodegradability [12]. Recent advancements in nanomaterial-based systems present novel strategies to tackle MDR planktonic and biofilm infections, acting as either intrinsic therapeutics or nanocarriers for antimicrobial drugs. Nanocomposites-based therapies, which have the capacity to sidestep established mechanisms associated with acquired drug resistance, are potential weapons against difficult-to-treat biofilm infections. Metal oxide nanoparticles (NPs) such as TiO2, CuO, ZnO, and Fe3O4 and several mixed metal oxides are among the most promising and frequently investigated NPs.

2. Structural and Functional Aspects of Microbial Biofilms

At interfaces, micro-organisms gather to create polymicrobial aggregates such as mats, films, or biofilms. The matrix can make up more than 90% of a biofilm’s dry mass, whereas the bacteria typically make up less than 10%. The extracellular matrix in which the biofilm cells are embedded is mostly created by the micro-organisms themselves. A self-produced matrix of hydrated EPS serves as the immediate habitat for the micro-organisms in biofilms. The EPS improves biofilm tolerance to antimicrobials and immune cells in addition to providing structural stability and a functioning environment [13][14]. The biofilm matrix retains water and holds the cells together. Because of the wide variety of matrix biopolymers, EPS has been referred to as “the house of biofilm cells” and “the dark matter of biofilms”. The major components of EPS include a blend of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. DNA assembles in the bacterium Pseudomonas putida pure cultures and the EPS matrix of activated sludge [15]. Extracellular DNA (e-DNA) in P. aeruginosa biofilms is probably derived from complete genomic DNA [16]. Surprisingly, e-DNA was arranged in different patterns and formed grid-like structures in the biofilms of this organism, indicating a structural role for e-DNA. Similarities and differences between the e-DNA and genomic DNA were evident. In the biofilms of an aquatic bacterium, e-DNA formed as a spatial structure producing a filamentous network [17]. The filaments appeared to act as nanowires, allowing the cells to migrate along them. One of the main matrix elements in P. aeruginosa biofilms was e-DNA, which served as an intercellular link. Numerous researchers endorsed the idea of stabilizing e-DNA’s function for the biofilm matrix [18]. The QS systems and iron regulation both regulate the release of e-DNA in P. aeruginosa [16][18]. The release of genomic DNA, a crucial structural component of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms, occurs as a result of cidA-controlled cell lysis, which is a critical factor in the development of S. aureus biofilms [19]. Biofilms are mechanically stable due to the EPS, which also facilitates their adherence to biotic or abiotic surfaces and creates a cohesive, three-dimensional (3D) polymer network that links biofilm cells and transiently immobilizes them. Intense interactions, such as cell–cell communication and the creation of synergistic microconsortia, are made possible by EPS, which stabilize the biofilm cells and retains them in close proximity; exopolysaccharides, which provide sites for cohesion and adhesion interactions; proteins, which serve as carbon and energy sources; and e-DNA. Furthermore, it is used for the transmission of resistance genes and the main components of EPS, which contributes to the overall establishment of biofilm structure [20]. The genetic make-up of strains, dietary requirements, and stages of biofilm formation all affect how important the EPS matrix is in relation to these factors [21]. The EPS of biofilms is well recognized for serving as a structural scaffold or a shield against hostile conditions [22][23]. The retention of extracellular enzymes results in the generation of a flexible external digestive system that sequesters dissolved and particulate nutrients from the aqueous phase so that they can be used as food and energy sources. It may turn out that the EPS matrix serves as much more than just a biofilm’s adhesive. Instead, it seems to be an extremely complex system that gives the biofilm a mode of life with specific and advantageous characteristics. More details regarding the precise biofilm EPS components, as well as their localization and stability, are likely to be detected. The revolutionary idea of “biofilm as a tissue” referred to EPS as the “glycocalyx” [24]. In this regard, intriguing research is demonstrating that EPS frequently has a distinct macromolecular “honeycomb” structure in a number of microbial communities [25][26]. Biofilms include a set of qualities that are important for life, including three-dimensional structure, adhesion to surfaces, adhesion to other biofilms, adhesion to one another, host defense mechanisms, and a reduction in antimicrobial resistance [27]. Limited diffusion through biofilm matrix causes serial resistance that negatively impacts the permeability of administered antibiotics. It is documented that using mild acid medications in these situations increases the permeability and efficiency of antibiotics [28]. Perhaps as inferred by functional divergence, EPS may be divided into three main categories: Class I includes architectural EPS, which play a role in signal as well as structural regulation. Class II includes protective EPS, which offer defence against physiological and immune response stresses induced by the host, and class III includes aggregative EPS, which play a role in adhesion and biofilm formation.

3. Biofilm Architecture

Transforming the expression patterns of cell surface molecules, virulence factors, and consumption pattern routes that enable growth under unfavourable conditions are all part of the complicated and dynamic process by which bacteria develop from free-living to multicellular communities [29]. Microbial cells and EPS are combined to form a stable biofilm structure, which has a predetermined architecture and offers the best conditions for the exchange of genetic material between cells. QS is another method through which cells can interact. This method may potentially influence biofilm processes like detachment. The understanding of biofilm architecture is necessary because it affects growth rate, fluid flow, and transfer of dissolved species, such as nutrients, metabolites, and disinfectants, across the biofilm/fluid interface and surface architecture [30]. Biofilm architecture may seem to be preferred in a state of needful/poor nutrient supply [31]. The total chemical exchange, biofilm permeability, flow resistance in constrained flow routes, and cell attachment/detachment and sloughing may all be assumed to depend on the surface architecture for a given surface density of biofilm biomass, which may affect a variety of practical applications. The development of biofilms and obstruction of downstream flow pathways are further impacted by detachment and sloughing. The method used to handle growth-induced stresses is particularly important for the establishment of surface architecture [30]. A measure of how frequently deviations occur over distances combined with the divergence from the average surface is known as the fractal dimension. While applying fractal dimensionality to biofilm height and length is undoubtedly helpful, comparing that fractality to other dimensions like height and width enables more sophisticated metrics for figuring out how architecture responds to environmental cues, including flow [32].

4. Nanocomposites-Based Therapeutics against Biofilm Infection

Nanocomposites-based medicines, which have the ability to circumvent established processes linked to acquired drug resistance, are prospective weapons against difficult-to-treat biofilm infections. Additionally, nanoparticles’ distinct shape and physical characteristics enable them to target biofilms and treat resistant illnesses. Researchers highlight the common ways that nanomaterials can be employed to combat bacterial infections brought about by biofilms and acquired antibiotic resistance. When compared to their bulk counterparts, materials at the nano-scale have exclusive physicochemical properties, such as size, shape, and surface. Nanomaterials’ distinctive qualities have revolutionized several technologies and sectors, including medicine. Nanomaterials can be created as novel treatment modalities since they can be made to have sizes equivalent to biomolecules and bacterial intracellular structures [33]. Biofilm-associated resistance, which exacerbates the treatment challenge when bacteria are present in biofilms, frequently necessitates physical removal of the biofilm by rigorous debridement, for example, together with large dosages of antibiotics [34]. These tactics may lead to expensive and time-consuming procedures that may have harmful side effects. Recent developments in nanomaterial-based systems provide new ways to combat MDR planktonic and biofilm infections, serving as either intrinsic therapies or as nanocarriers for antimicrobial medicines [35]. The therapeutic action of nanomaterials is influenced by their distinctive physicochemical characteristics, such as size, shape, and surface chemistry. In comparison to traditional antibiotics, nanomaterials may be less likely to induce resistance and can circumvent existing defense mechanisms [36]. Together with the aforementioned information, nanotechnology offers a new set of tools for developing MDR infection treatment options. Here, researchers explore the characteristics and features of therapeutic efficacy, shedding light on how nanomaterials could be modified to enhance their effectiveness against planktonic and biofilm infections.

5. Nanoparticle (NP) Interaction with Biofilms

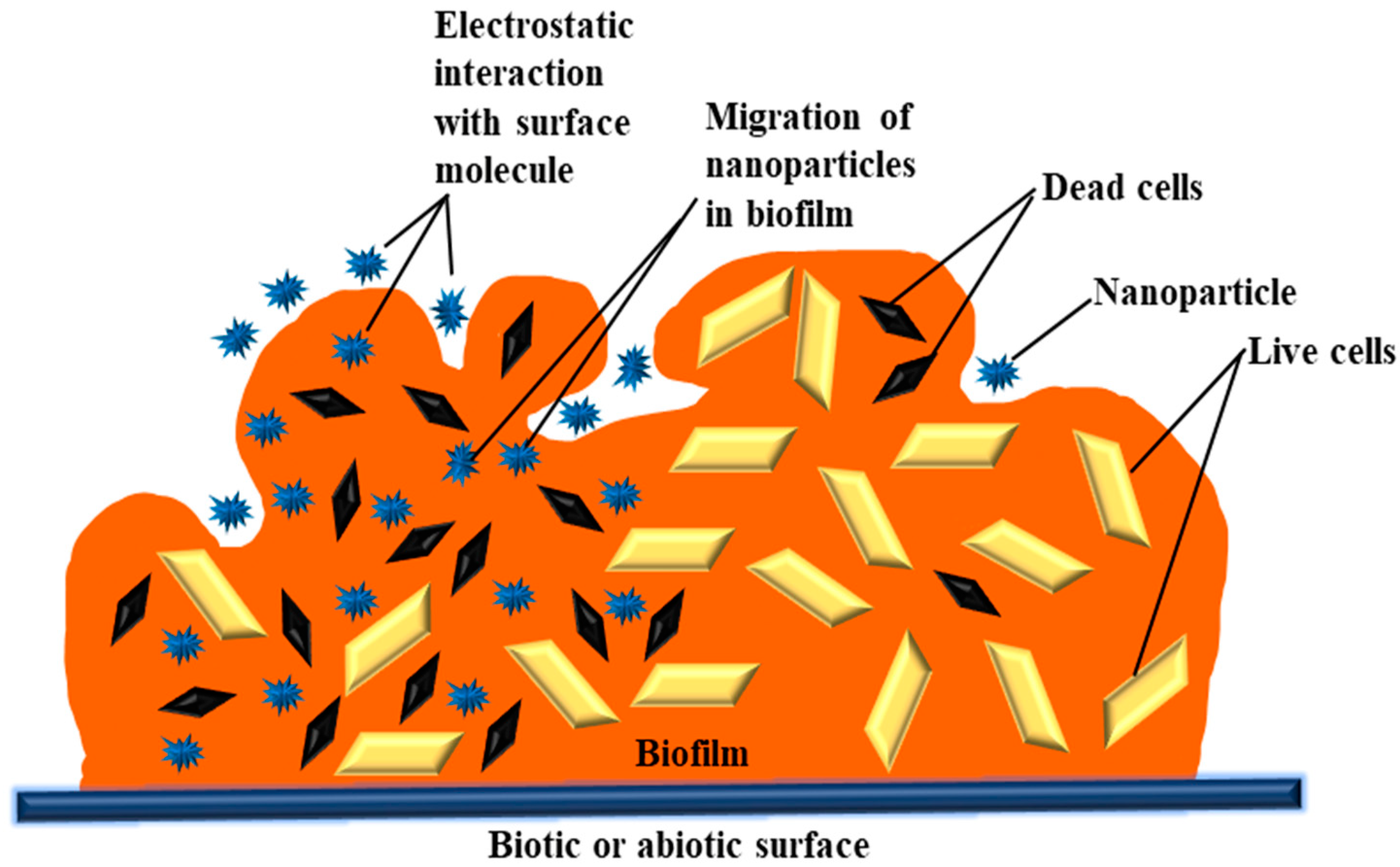

The EPM of biofilms is heterogeneous in terms of the physicochemical properties of a structure composed of numerous polymer molecules carrying an electric charge [37]. Therefore, a biofilm may be seen as a three-dimensional filter capable of removing NPs, organic compounds, and ions. Three stages may be thought of in the interaction between NPs and biofilms: (1) transfer of NPs nearby the biofilm; (2) adhesion to the biofilm surface; and (3) mobilization in biofilms (Figure 1). Each stage’s execution is influenced by a number of factors, including the environment, EPM, and, above all, the physicochemical characteristics of the NPs [38]. There are a number of physicochemical interactions that might influence the first attachment of NPs to the biofilms’ outermost surface. Their electrostatic properties play a major role in determining how NPs and biofilm interact. These characteristics are dependent on the NPs’ zeta potential and the biofilm matrix’s charge [39][40][41]. Due to the presence of uronic acid, metal-bound pyruvate, carboxylic acid, residual phosphate, and occasionally sulphate, most bacteria have a polyionic biofilm matrix [42][43]. Electrostatic forces enable this negatively charged matrix to interact with positively charged metal ions and organic molecules [44][45]. Successfully coupled NPs and EPM on the biofilm surface have different rates of deep penetration into the biofilm. Diffusion is assumed to be the primary cause of NP mobility and penetration inside the biofilm. Under these circumstances, the diffusion of NPs inside the biofilm may be affected by the size of its pores, the existence of water channels, the charge of the NPs, and the EPM [46][47]. The chemical gradient inside the matrix is determined by the hydrophobicity of the surroundings. In the water-containing EPM pore areas, different ion concentrations may exist. Ions and organic molecules move and disperse through these pore spaces throughout the biofilm. This suggests that the spacing between EPM pores may be particularly important in this process. However, this variation on a nanometer scale is not well understood and defined [48][49]. Thus, the charge, size, and composition of the particles, as well as the composition and structure of EPM, will all have a significant role in NP penetration and movement within the biofilm. The exact nature of this connection is yet very much unexplored.

Figure 1. Physicochemical interactions between metal oxide nanoparticles (NPs) and biofilm.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/life13010172

References

- Tallawi, M.; Opitz, M.; Lieleg, O. Modulation of the mechanical properties of bacterial biofilms in response to challenges. Biomater. Sci. 2017, 5, 887–900.

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575.

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633.

- Rumbaugh, K.P.; Diggle, S.P.; Watters, C.M.; Ross-Gillespie, A.; Grin, A.S.; West, S.A. Quorum sensing and the social evolution of bacterial virulence. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 341–345.

- Karatan, E.; Watnick, P. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 310–347.

- Crofts, T.S.; Gasparrini, A.J.; Dantas, G. Next-generation approaches to understand and combat the antibiotic resistome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 422–434.

- Alanis, A.J. Resistance to antibiotics: Are we in the post-antibiotic era? Arch. Med. Res. 2005, 36, 697–705.

- Jamal, M.; Ahmad, W.; Andleeb, S.; Jalil, F.; Imran, M.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, T.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, M.; Kamil, M.A. Bacterial biofilm and associated infections. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 7–11.

- Davies, J.D.D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 417–433.

- Plakunov, V.K.; Zhurina, M.V.; Gannesen, A.V.; Mart’yanov, S.V.; Nikolaev, Y.A. Antibiofilm agents: Therminological ambiguity and strategy for search. Microbiology 2019, 88, 747–750.

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318.

- Ozdal, M.; Gurkok, S. Recent advances in nanoparticles as antibacterial agent. ADMET DMPK 2022, 10, 115–129.

- Dragos, A.; Kovacs, A.T. The peculiar functions of the bacterial extracellular matrix. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 257–266.

- Koo, H.; Allan, R.N.; Howlin, R.P.; Stoodley, P.; Hall-Stoodley, L. Targeting microbial biofilms: Current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 740–755.

- Palmgren, M.R.; Nielsen, P.H. Accumulation of DNA in the exopolymeric matrix of activated sludge and bacterial cultures. Water Sci. Technol. 1996, 34, 233–240.

- Allesen-Holm, M.; Barken, K.B.; Yang, L.; Klausen, M.; Webb, J.S.; Kjelleberg, S.; Molin, S.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. A characterization of DNA release in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 1114–1128.

- Böckelmann, U.; Janke, A.; Kuhn, R.; Neu, T.R.; Wecke, J.; Lawrence, J.R.; Szewzyk, U. Bacterial extracellular DNA forming a defined network-like structure. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 262, 31–38.

- Yang, L.; Barken, K.B.; Skindersoe, M.E.; Christensen, A.B.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Effects of iron on DNA release and biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1318–1328.

- Rice, K.C.; Mann, E.E.; Endres, J.L.; Weiss, E.C.; Cassat, J.E.; Smeltzer, M.S.; Bayles, K.W. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8113–8118.

- Limoli, D.H.; Jones, C.J.; Wozniak, D.J. Bacterial extracellular polysaccharides in biofilm formation and function. Microbiol Spectr. 2015, 3, 3.

- Flemming, H.C.; Neu, T.R.; Wozniak, D.J. The EPS matrix: The “house of biofilm cells”. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7945–7947.

- Ryder, C.; Byrd, M.; Wozniak, D.J. Role of polysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2007, 10, 644–648.

- Parsek, M.R.; Singh, P.K. Bacterial biofilms: An emerging link to disease pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 57, 677–701.

- Costerton, J.W.; Irvin, R.T. The bacterial glycocalyx in nature and disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1981, 35, 299–324.

- Schaudinn, C.; Stoodley, P.; Kainovic, A.; O Keeffe, T.; Costerton, B.; Robinson, D.; Baum, M.; Ehrlich, G.; Webster, P. Bacterial biofilms, other structures seen as mainstream concepts. Microbe Am. Soc. Microb. 2007, 2, 231–237.

- Thar, R.; Kuhl, M. Conspicuous veils formed by vibrioid bacteria on sulfidic marine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6310–6320.

- Kundukad, B.; Schussman, M.; Yang, K.; Seviour, T.; Yang, L.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Doyle, P.S. Mechanistic action of weak acid drugs on biofilms. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4783.

- Kostakioti, M.; Hadjifrangiskou, M.; Hultgren, S.J. Bacterial biofilms: Development, dispersal, and therapeutic strategies in the dawn of the post antibiotic era. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2013, 3, a010306.

- Fowler, A.C.; Kyrke-Smith, T.M.; Winstanley, H.F. The development of biofilm architecture. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 472, 20150798.

- Heydorn, A.; Nielsen, A.T.; Hentzer, M.; Sternberg, C.; Givskov, M.; Ersbøll, B.K.; Molin, S. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 2000, 146, 2395–2407.

- Hermanowicz, S.; Schindler, U.; Wilderer, P. Fractal structure of biofilms: New tools for investigation of morphology. Water Sci. Technol. 1995, 32, 99–105.

- Coquet, L.; Junter, G.A.; Jouenne, T. Resistance of artificial biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to imipenem and tobramycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1998, 42, 755–760.

- Baptista, P.V.; McCusker, M.P.; Carvalho, A.; Ferreira, D.A.; Mohan, N.M.; Martins, M.; Fernandes, A.R. Nano-strategies to fight multidrug resistant bacteria—“A Battle of the Titans”. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1441.

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L. Implant infections: Adhesion, biofilm formation and immune evasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 397–409.

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: Present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1227.

- Pelgrift, R.Y.; Friedman, A.J. Nanotechnology as a therapeutic tool to combat microbial resistance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1803–1815.

- Kohanski, M.A.; Dwyer, D.J.; Hayete, B.; Lawrence, C.A.; Collins, J.J. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 2007, 130, 797–810.

- Shkodenko, L.; Kassirov, I.; Koshel, E. Metal oxide nanoparticles against bacterial biofilms: Perspectives and limitations. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1545.

- Liang, Y.; Hilal, N.; Langston, P.; Starov, V. Interaction forces between colloidal particles in liquid: Theory and experiment. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 134, 151–166.

- Ikuma, K.; Madden, A.S.; Decho, A.W.; Lau, B.L. Deposition of nanoparticles onto polysaccharide-coated surfaces: Implications for nanoparticle–biofilm interactions. Environ. Sci. 2014, 1, 117–122.

- Tong, M.; Ding, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, P. Influence of biofilm on the transport of fullerene (C60) nanoparticles in porous media. Water Res. 2010, 44, 1094–1103.

- Hajipour, M.J.; Fromm, K.M.; Ashkarran, A.A.; de Aberasturi, D.J.; de Larramendi, I.R.; Rojo, T.; Serpooshan, V.; Parak, W.J.; Mahmoudi, M. Antibacterial properties of nanoparticles. Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 499–511.

- Sutherland, I.W. Biofilm exopolysaccharides: A strong and sticky framework. Microbiology 2001, 147, 3–9.

- Esparza-Soto, M.; Westerhoff, P. Biosorption of humic and fulvic acids to live activated sludge biomass. Water Res. 2003, 37, 2301–2310.

- Selvakumar, R.; Aravindh, S.; Ashok, A.M.; Balachandran, Y.L. A facile synthesis of silver nanoparticle with SERS and antimicrobial activity using Bacillus subtilis exopolysaccharides. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2014, 9, 1075–1087.

- Peulen, T.O.; Wilkinson, K.J. Diffusion of nanoparticles in a biofilm. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3367–3373.

- Stewart, P.S. Diffusion in biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 1485–1491.

- Habimana, O.; Steenkeste, K.; Fontaine-Aupart, M.P.; Bellon-Fontaine, M.N.; Kulakauskas, S.; Briandet, R. Diffusion of nanoparticles in biofilms is altered by bacterial cell wall hydrophobicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 367–368.

- Ikuma, K.; Decho, A.W.; Lau, B.L. When nanoparticles meet biofilms—Interactions guiding the environmental fate and accumulation of nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 591.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!