Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) is a common neurological disorder with devastating psychical and psychosocial sequelae. The majority of patients after SCI suffer from permanent disability caused by motor dysfunction, impaired sensation, neuropathic pain, spasticity as well as urinary complications, and a small number of patients experience a complete recovery. Current standard treatment modalities of the SCI aim to prevent secondary injury and provide limited recovery of lost neurological functions. Stem Cell Therapy (SCT) represents an emerging treatment approach using the differentiation, paracrine, and self-renewal capabilities of stem cells to regenerate the injured spinal cord. Multipotent stem cells including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), neural stem cells (NSCs), and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) represent the most investigated types of stem cells for the treatment of SCI in preclinical and clinical studies. The microenvironment of SCI has a significant impact on the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of transplanted stem cells.

- spinal cord injuries

- stem cell transplantation

- multipotent stem cells

- mesenchymal stem cells

- neural stem cells

- hematopoietic stem cells

1. Introduction

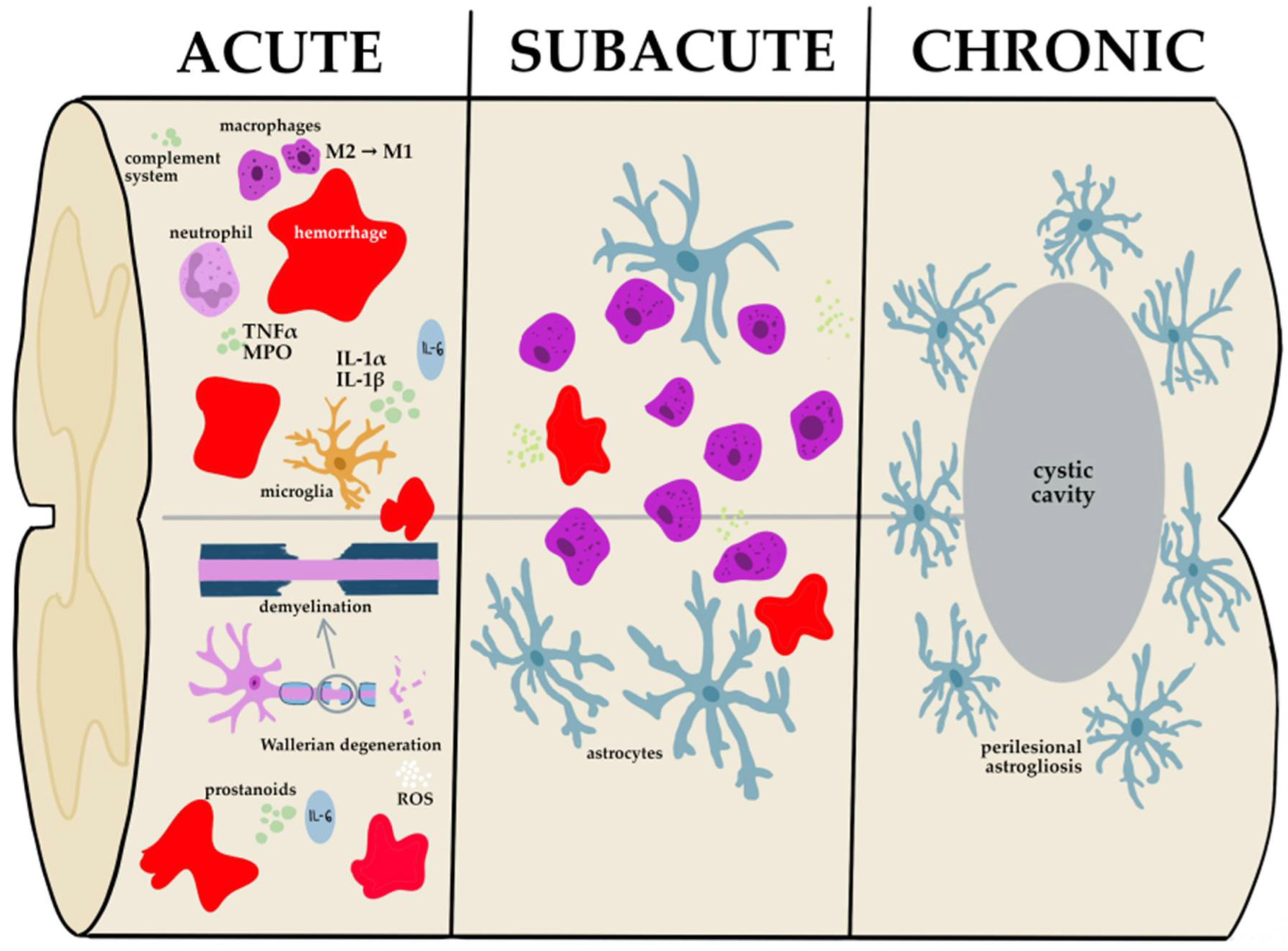

2. Pathophysiology of Spinal Cord Injury

3. Stem Cell Types for Stem Cell Therapy

3.1. Stem Cells’ Classification

3.2. Pluripotent Stem Cells

3.3. Multipotent Stem Cells

|

Type of Stem Cells |

Differentiation Potential |

Sourcing |

Main Advantages |

Limitations |

Application in Spinal Cord Injury |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Embryonal Stem Cells |

totipotent, pluripotent |

morula, blastocyst, umbilical cord, amniotic fluid, amnion, chorion, generated from adult somatic cells |

possibility to generate any cell lines, e.g., neurons or oligodendrocytes |

the risk of immune rejection, the ethical concern regarding the use of human embryos, the risk of tumorigenicity |

Preclinical studies |

|

|

Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

pluripotent |

generated from adult somatic cells using so-called OSKM transcription factors |

lack of ethical issues and immune suppression (in autologous method) |

the risk of immune rejections, instability of iPSCs’ genome, potential tumorigenicity |

Preclinical studies |

|

|

Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

multipotent |

bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, adipose tissue |

capability to generate adipocytes, bone, and chondrocytes, easy extraction, rapid proliferation, low immunogenicity; ADMSCs and BMSCs can be generated without ethical issues |

ADMSCs and BMSCs require liposuction or bone marrow aspirate followed by cultivation, which makes them time-consuming, and expensive sources; Umbilical cord or Wharton’s Jelly MSCs require conducting complex procedures namely lyophilization to avoid immunological responses and are controversial from the ethical point of view |

Clinical studies |

|

|

Hematopoietic Stem Cells |

multipotent |

placenta, cord blood, adult bone marrow |

capability to differentiate into all cell types of the hematopoietic system, treatment for many diseases such as hematopoietic diseases, multiple sclerosis, Cron’s disease, and diabetes |

the risk of immune rejection |

Clinical studies |

|

|

Neural Stem Cells |

multipotent |

ventricular system of the brain, central canal of the spinal cord, dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, differentiation from somatic cells, iPSCs |

capability to differentiate into neurons, oligodentrocytes and astrocytes |

the risk of immune rejection, low progress of the research due to ethical and financial problems |

Clinical studies |

[91] |

4. Molecular Mechanisms of Multipotent Stem Cells at SCI Microenvironment

4.1. Mesenchymal Stem Cells

4.2. Neural Stem Cells

4.3. Hematopoietic Stem Cells

5. Novel Therapeutic Approaches Based on Stem Cell Therapy

|

Technology |

Phase of Studies |

Advantages |

Limitations |

Refs |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stem cell-derived exosomes |

preclinical |

comparable effectiveness with SCT avoids immune rejection and risk of carcinogenicity, avoids problems with low survival rate, dedifferentiation, and difficult obtainment of stem cells |

not entirely studied the content of exosomes, lack of unified obtainment procedure, unstandardized number of injections, its frequency, and dosage |

||

|

Gene-modified stem cells |

preclinical |

better outcomes compared with non-modified stem cells, enables manipulation of the specific molecular pathways of spinal cord injury microenvironment to enhance treatment efficacy |

safety concerns regarding the use of viral vectors for genetic engineering |

[162] |

|

|

Biomaterials |

Cell-free 3D-printed scaffolds |

preclinical |

creates a suitable microenvironment for stem cells, provides a bridging role, improves neural regeneration, resistance to toxic, temperature, and UV radiation during the fabrication process |

immune rejection, cumbersome bioprinting procedure, limited availability of printable bioinks |

|

|

3D-printed scaffold loaded with stem cells |

preclinical |

possibility to create a "spinal cord-like" scaffold |

restricted conditions of the manufacturing process, immune rejection, cumbersome bioprinting procedure, limited availability of printable bioinks |

||

|

Hydrogels |

clinical |

high biocompatibility may be used as a cell or cell factors’ carrier for its transport into the lesion site |

fast degradation rate, low mechanical strength, and durability |

[91] |

|

|

Nanomaterials |

preclinical |

improves stem cell transport and viability |

not established release time and dose of drugs loaded on nanoparticles |

[91] |

|

5.1. Stem-Cell-Derived Exosomes

5.2. Gene-Modified Stem Cells

5.3. Biomaterials

6. Challenges, Barriers, and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells12010120

References

- Lo, J.; Chan, L.; Flynn, S. A Systematic Review of the Incidence, Prevalence, Costs, and Activity/Work Limitations of Amputation, Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Back Pain, Multiple Sclerosis, Spinal Cord Injury, Stroke, and Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: A 2019 Update. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 115.

- Chay, W.; Kirshblum, S. Predicting Outcomes After Spinal Cord Injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 31, 331–343.

- Michel, M.; Goldman, M.; Peart, R.; Martinez, M.; Reddy, R.; Lucke-Wold, B. Spinal Cord Injury: A Review of Current Management Considerations and Emerging Treatments. J. Neurol. Sci. Res. 2021, 2, 14.

- Haddad, A.F.; Burke, J.F.; Dhall, S.S. The Natural History of Spinal Cord Injury. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 32, 315–321.

- Golestani, A.; Shobeiri, P.; Sadeghi-Naini, M.; Jazayeri, S.B.; Maroufi, S.F.; Ghodsi, Z.; Dabbagh Ohadi, M.A.; Mohammadi, E.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V.; Ghodsi, S.M. Epidemiology of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Developing Countries from 2009 to 2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2022, 56, 219–239.

- Kim, G.-U.; Sung, S.-E.; Kang, K.-K.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, S.; Sung, M.; Yang, S.Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, Y.I.; Lim, J.-H.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) and MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3672.

- Smith, É.; Fitzpatrick, P.; Lyons, F.; Morris, S.; Synnott, K. Epidemiology of Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury in Ireland—A Prospective Population-Based Study. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2022, 45, 76–81.

- Litak, J.; Czyżewski, W.; Szymoniuk, M.; Sakwa, L.; Pasierb, B.; Litak, J.; Hoffman, Z.; Kamieniak, P.; Roliński, J. Biological and Clinical Aspects of Metastatic Spinal Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 4599.

- Gober, J.; Thomas, S.P.; Gater, D.R. Pediatric Spina Bifida and Spinal Cord Injury. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 985.

- Sahbani, K.; Cardozo, C.P.; Bauman, W.A.; Tawfeek, H.A. Inhibition of TGF-Beta Signaling Attenuates Disuse-Induced Trabecular Bone Loss After Spinal Cord Injury in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqab230.

- Fehlings, M.G.; Tetreault, L.A.; Wilson, J.R.; Aarabi, B.; Anderson, P.; Arnold, P.M.; Brodke, D.S.; Burns, A.S.; Chiba, K.; Dettori, J.R.; et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Spinal Cord Injury and Central Cord Syndrome: Recommendations on the Timing (≤24 Hours Versus >24 Hours) of Decompressive Surgery. Glob. Spine J. 2017, 7, 195S–202S.

- Fehlings, M.G.; Wilson, J.R.; Tetreault, L.A.; Aarabi, B.; Anderson, P.; Arnold, P.M.; Brodke, D.S.; Burns, A.S.; Chiba, K.; Dettori, J.R.; et al. A Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Recommendations on the Use of Methylprednisolone Sodium Succinate. Glob. Spine J. 2017, 7, 203S–211S.

- Wang, T.Y.; Park, C.; Zhang, H.; Rahimpour, S.; Murphy, K.R.; Goodwin, C.R.; Karikari, I.O.; Than, K.D.; Shaffrey, C.I.; Foster, N.; et al. Management of Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Review of the Literature. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 698736.

- Albu, S.; Kumru, H.; Coll, R.; Vives, J.; Vallés, M.; Benito-Penalva, J.; Rodríguez, L.; Codinach, M.; Hernández, J.; Navarro, X.; et al. Clinical Effects of Intrathecal Administration of Expanded Wharton Jelly Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Patients with Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury: A Randomized Controlled Study. Cytotherapy 2021, 23, 146–156.

- Costăchescu, B.; Niculescu, A.G.; Dabija, M.G.; Teleanu, R.I.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Eva, L. Novel Strategies for Spinal Cord Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4552.

- Hoang, D.M.; Pham, P.T.; Bach, T.Q.; Ngo, A.T.L.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Phan, T.T.K.; Nguyen, G.H.; Le, P.T.T.; Hoang, V.T.; Forsyth, N.R.; et al. Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 272.

- Pucułek, M.; Baj, J.; Portincasa, P.; Sitarz, M.; Grochowski, C.; Radzikowska, E. The Morphology and Application of Stem Cells in Digestive System Surgery. Folia Morphol. 2021, 80, 13–19.

- Li, T.-T.; Wang, Z.-R.; Yao, W.-Q.; Linghu, E.-Q.; Wang, F.-S.; Shi, L. Stem Cell Therapies for Chronic Liver Diseases: Progress and Challenges. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 900–911.

- Gruca, D.; Zając, M.; Wróblewski, W.; Borowiecka, M.; Buksak, D. The Relation between Adipose-Derived Stem Cells and Wound Healing Process—The Review. J. Educ. Health Sport 2022, 12, 87–93.

- Sarsenova, M.; Issabekova, A.; Abisheva, S.; Rutskaya-Moroshan, K.; Ogay, V.; Saparov, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1592.

- Hassanzadeh, A.; Shamlou, S.; Yousefi, N.; Nikoo, M.; Verdi, J. Genetically-Modified Stem Cell in Regenerative Medicine and Cancer Therapy; A New Era. Curr. Gene Ther. 2022, 22, 23–39.

- Puranik, N.; Arukha, A.P.; Yadav, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Jin, J.O. Exploring the Role of Stem Cell Therapy in Treating Neurodegenerative Diseases: Challenges and Current Perspectives. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 17, 113–125.

- Ejma, M.; Madetko, N.; Brzecka, A.; Alster, P.; Budrewicz, S.; Koszewicz, M.; Misiuk-Hojło, M.; Tomilova, I.K.; Somasundaram, S.G.; Kirkland, C.E. The Role of Stem Cells in the Therapy of Stroke. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 630–647.

- Peterson, S.; Jalil, A.; Beard, K.; Kakara, M.; Sriwastava, S. Updates on Efficacy and Safety Outcomes of New and Emerging Disease Modifying Therapies and Stem Cell Therapy for Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 68, 104125.

- Li, X.; Sundström, E. Stem Cell Therapies for Central Nervous System Trauma: The 4 Ws—What, When, Where, and Why. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 14–25.

- Zipser, C.M.; Cragg, J.J.; Guest, J.D.; Fehlings, M.G.; Jutzeler, C.R.; Anderson, A.J.; Curt, A. Cell-Based and Stem-Cell-Based Treatments for Spinal Cord Injury: Evidence from Clinical Trials. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 659–670.

- Saini, R.; Pahwa, B.; Agrawal, D.; Singh, P.K.; Gujjar, H.; Mishra, S.; Jagdevan, A.; Misra, M.C. Efficacy and Outcome of Bone Marrow Derived Stem Cells Transplanted via Intramedullary Route in Acute Complete Spinal Cord Injury—A Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 100, 7–14.

- Yang, Y.; Pang, M.; Du, C.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Chen, Z.-H.; Wang, N.-X.; Zhang, L.-M.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Mo, J.; Dong, J.-W.; et al. Repeated Subarachnoid Administrations of Allogeneic Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: A Phase 1/2 Pilot Study. Cytotherapy 2021, 23, 57–64.

- Hur, J.W.; Cho, T.H.; Park, D.H.; Lee, J.B.; Park, J.Y.; Chung, Y.G. Intrathecal Transplantation of Autologous Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Treating Spinal Cord Injury: A Human Trial. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2016, 39, 655–664.

- Curt, A.; Hsieh, J.; Schubert, M.; Hupp, M.; Friedl, S.; Freund, P.; Huber, E.; Pfyffer, D.; Sutter, R.; Jutzeler, C.; et al. The Damaged Spinal Cord Is a Suitable Target for Stem Cell Transplantation. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 758–768.

- Levi, A.D.; Anderson, K.D.; Okonkwo, D.O.; Park, P.; Bryce, T.N.; Kurpad, S.N.; Aarabi, B.; Hsieh, J.; Gant, K. Clinical Outcomes from a Multi-Center Study of Human Neural Stem Cell Transplantation in Chronic Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 891–902.

- Smirnov, V.A.; Radaev, S.M.; Morozova, Y.V.; Ryabov, S.I.; Yadgarov, M.Y.; Bazanovich, S.A.; Lvov, I.S.; Talypov, A.E.; Grin’, A.A. Systemic Administration of Allogeneic Cord Blood Mononuclear Cells in Adults with Severe Acute Contusion Spinal Cord Injury: Phase 1/2a Pilot Clinical Study-Safety and Primary Efficacy Evaluation. World Neurosurg. 2022, 161, e319–e338.

- Gant, K.L.; Guest, J.D.; Palermo, A.E.; Vedantam, A.; Jimsheleishvili, G.; Bunge, M.B.; Brooks, A.E.; Anderson, K.D.; Thomas, C.K.; Santamaria, A.J.; et al. Phase 1 Safety Trial of Autologous Human Schwann Cell Transplantation in Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 285–299.

- Tabakow, P.; Jarmundowicz, W.; Czapiga, B.; Fortuna, W.; Miedzybrodzki, R.; Czyz, M.; Huber, J.; Szarek, D.; Okurowski, S.; Szewczyk, P.; et al. Transplantation of Autologous Olfactory Ensheathing Cells in Complete Human Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Transplant. 2013, 22, 1591–1612.

- Rövekamp, M.; von Glinski, A.; Volkenstein, S.; Dazert, S.; Sengstock, C.; Schildhauer, T.A.; Breisch, M. Olfactory Stem Cells for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury-A New Pathway to the Cure? World Neurosurg. 2022, 161, e408–e416.

- Fessler, R.G.; Ehsanian, R.; Liu, C.Y.; Steinberg, G.K.; Jones, L.; Lebkowski, J.S.; Wirth, E.D.; McKenna, S.L. A Phase 1/2a Dose-Escalation Study of Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Cells in Individuals with Subacute Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2022, 37, 812–820.

- Ahuja, C.S.; Nori, S.; Tetreault, L.; Wilson, J.; Kwon, B.; Harrop, J.; Choi, D.; Fehlings, M.G. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury—Repair and Regeneration. Clin. Neurosurg. 2017, 80, S22–S90.

- Garcia, E.; Aguilar-Cevallos, J.; Silva-Garcia, R.; Ibarra, A. Cytokine and Growth Factor Activation in Vivo and in Vitro after Spinal Cord Injury. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 9476020.

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, F.; Zhou, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, S. Ferroptosis: A Novel Therapeutic Direction of Spinal Cord Injury. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 790621.

- Slater, P.G.; Domínguez-Romero, M.E.; Villarreal, M.; Eisner, V.; Larraín, J. Mitochondrial Function in Spinal Cord Injury and Regeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 1–24.

- Salman, M.M.; Kitchen, P.; Halsey, A.; Wang, M.X.; Törnroth-Horsefield, S.; Conner, A.C.; Badaut, J.; Iliff, J.J.; Bill, R.M. Emerging Roles for Dynamic Aquaporin-4 Subcellular Relocalization in CNS Water Homeostasis. Brain 2022, 145, 64–75.

- Fan, B.; Wei, Z.; Yao, X.; Shi, G.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H.; Ning, G.; Kong, X.; Feng, S. Microenvironment Imbalance of Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 853–866.

- Beirowski, B.; Nógrádi, A.; Babetto, E.; Garcia-Alias, G.; Coleman, M.P. Mechanisms of Axonal Spheroid Formation in Central Nervous System Wallerian Degeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 455–472.

- Alizadeh, A.; Dyck, S.M.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 282.

- Jia, M.; Njapo, S.A.N.; Rastogi, V.; Hedna, V.S. Taming Glutamate Excitotoxicity: Strategic Pathway Modulation for Neuroprotection. CNS Drugs 2015, 29, 153–162.

- Brat, D.J. Normal Brain Histopathology. In Practical Surgical Neuropathology: A Diagnostic Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 19–37.

- Sharma, K.; Zhang, G.; Li, S. Astrogliosis and Axonal Regeneration. Neural Regen. 2015, 181–196.

- Bacakova, L.; Zarubova, J.; Travnickova, M.; Musilkova, J.; Pajorova, J.; Slepicka, P.; Kasalkova, N.S.; Svorcik, V.; Kolska, Z.; Motarjemi, H.; et al. Stem Cells: Their Source, Potency and Use in Regenerative Therapies with Focus on Adipose-Derived Stem Cells—A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1111–1126.

- Sobhani, A.; Sobhani, A.; Khanlarkhani, N.; Baazm, M.; Mohammadzadeh, F.; Najafi, A.; Mehdinejadiani, S.; Aval, F.S. Multipotent Stem Cell and Current Application. Acta Med. Iran. 2017, 55, 6–23.

- Zakrzewski, W.; Dobrzyński, M.; Szymonowicz, M.; Rybak, Z. Stem Cells: Past, Present, and Future. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 68.

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872.

- Dulak, J.; Szade, K.; Szade, A.; Nowak, W.; Józkowicz, A. Adult Stem Cells: Hopes and Hypes of Regenerative Medicine* Definition of Stem and Progenitor Cell. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2015, 62, 329–337.

- Mirzaei, H.; Sahebkar, A.; Sichani, L.S.; Moridikia, A.; Nazari, S.; Nahand, J.S.; Salehi, H.; Stenvang, J.; Masoudifar, A.; Mirzaei, H.R.; et al. Therapeutic Application of Multipotent Stem Cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 2815–2823.

- Paliwal, S.; Fiumera, H.L.; Mohanty, S. Stem Cell Plasticity and Regenerative Potential Regulation through Ca2+-Mediated Mitochondrial Nuclear Crosstalk. Mitochondrion 2021, 56, 1–14.

- Grochowski, C.; Radzikowska, E.; Maciejewski, R. Neural Stem Cell Therapy—Brief Review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 173, 8–14.

- Hawkins, K.E.; Corcelli, M.; Dowding, K.; Ranzoni, A.M.; Vlahova, F.; Hau, K.L.; Hunjan, A.; Peebles, D.; Gressens, P.; Hagberg, H.; et al. Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) Have a Superior Neuroprotective Capacity Over Fetal MSCs in the Hypoxic-Ischemic Mouse Brain. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 439–449.

- Xia, Y.; Hu, G.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Z. Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Modulate Regulatory T Cells to Protect against Ischemic Stroke. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 7370–7385.

- Wang, X.; Kimbrel, E.A.; Ijichi, K.; Paul, D.; Lazorchak, A.S.; Chu, J.; Kouris, N.A.; Yavanian, G.J.; Lu, S.J.; Pachter, J.S.; et al. Human ESC-Derived MSCs Outperform Bone Marrow MSCs in the Treatment of an EAE Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 370–371.

- Araki, R.; Mizutani, E.; Hoki, Y.; Sunayama, M.; Wakayama, S.; Nagatomo, H.; Kasama, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Wakayama, T.; Abe, M. The Number of Point Mutations in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Nuclear Transfer Embryonic Stem Cells Depends on the Method and Somatic Cell Type Used for Their Generation. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 1189–1196.

- Mousaei Ghasroldasht, M.; Seok, J.; Park, H.S.; Liakath Ali, F.B.; Al-Hendy, A. Stem Cell Therapy: From Idea to Clinical Practice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2850.

- Poetsch, M.S.; Strano, A.; Guan, K. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: From Cell Origin, Genomic Stability, and Epigenetic Memory to Translational Medicine. Stem Cells 2022, 40, 546–555.

- Du, X.; Amponsah, A.E.; Kong, D.; He, J.; Ma, Z.; Ma, J.; Cui, H. HiPSC-Neural Stem/Progenitor Cell Transplantation Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 17.

- Ji, P.; Manupipatpong, S.; Xie, N.; Li, Y. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells: Generation Strategy and Epigenetic Mystery behind Reprogramming. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 8415010.

- Fu, X. The Immunogenicity of Cells Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 14.

- Lee, A.S.; Tang, C.; Rao, M.S.; Weissman, I.L.; Wu, J.C. Tumorigenicity as a Clinical Hurdle for Pluripotent Stem Cell Therapies. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 998–1004.

- Attia, N.; Mashal, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: The Past Present and Future. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1312, 107–129.

- Oh, S.K.; Choi, K.H.; Yoo, J.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Jeon, S.R. A Phase III Clinical Trial Showing Limited Efficacy of Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Spinal Cord Injury. Neurosurgery 2016, 78, 436–447.

- Vaquero, J.; Zurita, M.; Rico, M.A.; Aguayo, C.; Fernandez, C.; Rodriguez-Boto, G.; Marin, E.; Tapiador, N.; Sevilla, M.; Carballido, J.; et al. Cell Therapy with Autologous Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Post-Traumatic Syringomyelia. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 796–805.

- Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Hu, J. Efficient One-Step Induction of Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (UC-MSCs) Produces MSC-Derived Neurospheres (MSC-NS) with Unique Transcriptional Profile and Enhanced Neurogenic and Angiogenic Secretomes. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 9208173.

- Qu, J.; Zhang, H. Roles of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cells Int. 2017, 2017, 5251313.

- Cofano, F.; Boido, M.; Monticelli, M.; Zenga, F.; Ducati, A.; Vercelli, A.; Garbossa, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: Current Options, Limitations, and Future of Cell Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2698.

- Jiang, W.; Xu, J. Immune Modulation by Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Prolif. 2020, 53, e12712.

- Muthu, S.; Jeyaraman, M.; Gulati, A.; Arora, A. Current Evidence on Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cytotherapy 2021, 23, 186–197.

- Han, S.; Sun, H.M.; Hwang, K.C.; Kim, S.W. Adipose-Derived Stromal Vascular Fraction Cells: Update on Clinical Utility and Efficacy. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2015, 25, 145–152.

- Berebichez-Fridman, R.; Montero-Olvera, P.R. Sources and Clinical Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: State-of-the-Art Review. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2018, 18, e264.

- Marino, L.; Castaldi, M.A.; Rosamilio, R.; Ragni, E.; Vitolo, R.; Fulgione, C.; Castaldi, S.G.; Serio, B.; Bianco, R.; Guida, M.; et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells from the Wharton’s Jelly of the Human Umbilical Cord: Biological Properties and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Stem Cells 2019, 12, 218–226.

- Liau, L.L.; Looi, Q.H.; Chia, W.C.; Subramaniam, T.; Ng, M.H.; Law, J.X. Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury with Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 112.

- Anderson, K.D.; Guest, J.D.; Dietrich, W.D.; Bartlett Bunge, M.; Curiel, R.; Dididze, M.; Green, B.A.; Khan, A.; Pearse, D.D.; Saraf-Lavi, E.; et al. Safety of Autologous Human Schwann Cell Transplantation in Subacute Thoracic Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 2950–2963.

- Andreopoulou, E.; Arampatzis, A.; Patsoni, M.; Kazanis, I. Being a Neural Stem Cell: A Matter of Character but Defined by the Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1041, 81–118.

- Shahbazi, E.; Moradi, S.; Nemati, S.; Satarian, L.; Basiri, M.; Gourabi, H.; Zare Mehrjardi, N.; Günther, P.; Lampert, A.; Händler, K.; et al. Conversion of Human Fibroblasts to Stably Self-Renewing Neural Stem Cells with a Single Zinc-Finger Transcription Factor. Stem Cell Rep. 2016, 6, 539–551.

- García-González, D.; Murcia-Belmonte, V.; Esteban, P.F.; Ortega, F.; Díaz, D.; Sánchez-Vera, I.; Lebrón-Galán, R.; Escobar-Castañondo, L.; Martínez-Millán, L.; Weruaga, E.; et al. Anosmin-1 over-Expression Increases Adult Neurogenesis in the Subventricular Zone and Neuroblast Migration to the Olfactory Bulb. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016, 221, 239–260.

- Danielson, N.; Byrne, M. Indications for Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep. 2020, 15, 268–275.

- Mohammadi, R.; Aryan, A.; Omrani, M.D.; Ghaderian, S.M.H.; Fazeli, Z. Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (AHSCT): An Evolving Treatment Avenue in Multiple Sclerosis. Biologics 2021, 15, 53–59.

- Oliveira, M.C.; Elias, J.B.; de Moraes, D.A.; Simões, B.P.; Rodrigues, M.; Ribeiro, A.A.F.; Piron-Ruiz, L.; Ruiz, M.A.; Hamerschlak, N. A Review of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Autoimmune Diseases: Multiple Sclerosis, Systemic Sclerosis and Crohn’s Disease. Position Paper of the Brazilian Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2021, 43, 65–86.

- Nikoonezhad, M.; Lasemi, M.V.; Alamdari, S.; Mohammadian, M.; Tabarraee, M.; Ghadyani, M.; Hamidpour, M.; Roshandel, E. Treatment of Insulin-Dependent Diabetes by Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transpl. Immunol. 2022, 75, 101682.

- Koda, M.; Okada, S.; Nakayama, T.; Koshizuka, S.; Kamada, T.; Nishio, Y.; Someya, Y.; Yoshinaga, K.; Okawa, A.; Moriya, H.; et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell and Marrow Stromal Cell for Spinal Cord Injury in Mice. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1763–1767.

- Ozdemir, Z.N.; Civriz Bozdağ, S. Graft Failure after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2018, 57, 163–167.

- Deda, H.; Inci, M.C.; Kurekçi, A.; Kayihan, K.; Özgün, E.; Ustunsoy, G.; Kocabay, S. Treatment of Chronic Spinal Cord Injured Patients with Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: 1-Year Follow-Up. Cytotherapy 2008, 10, 565–574.

- Müller, A.M.; Huppertz, S.; Henschler, R. Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine: Astray or on the Path? Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 2016, 43, 247–254.

- Mosaad, Y.M. Hematopoietic Stem Cells: An Overview. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2014, 51, 68–82.

- Hou, Y.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, D.; Guo, P.; Liu, J. Strategies for Effective Neural Circuit Reconstruction After Spinal Cord Injury: Use of Stem Cells and Biomaterials. World Neurosurg. 2022, 161, 82–89.

- Zhao, A.; Chung, M.; Yang, Y.; Pan, X.; Pan, Y.; Cai, S. The SDF-1/CXCR4 Signaling Pathway Directs the Migration of Systemically Transplanted Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells towards the Lesion Site in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 18, 216–230.

- Pelagalli, A.; Nardelli, A.; Lucarelli, E.; Zannetti, A.; Brunetti, A. Autocrine Signals Increase Ovine Mesenchymal Stem Cells Migration through Aquaporin-1 and CXCR4 Overexpression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6241–6249.

- Marquez-Curtis, L.A.; Gul-Uludag, H.; Xu, P.; Chen, J.; Janowska-Wieczorek, A. CXCR4 Transfection of Cord Blood Mesenchymal Stromal Cells with the Use of Cationic Liposome Enhances Their Migration toward Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1. Cytotherapy 2013, 15, 840–849.

- Xie, J.-L.; Wang, X.-R.; Li, M.-M.; Tao, Z.-H.; Teng, W.-W. Saijilafu Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Spinal Cord Injury: Mechanisms and Prospects. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 270.

- Bang, O.Y.; Moon, G.J.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.; Son, J.P.; Cho, Y.H.; Chang, W.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Sung, J.H.; et al. Stroke Induces Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration to Infarcted Brain Areas Via CXCR4 and C-Met Signaling. Transl. Stroke Res. 2017, 8, 449–460.

- He, W.; Shi, C.; Yin, J.; Huang, F.; Yan, W.; Deng, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, H. Spinal Cord Decellularized Matrix Scaffold Loaded with Engineered Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor-Overexpressed Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promoted the Recovery of Spinal Cord Injury. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2022, 111, 51–61.

- Song, P.; Han, T.; Xiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fang, H.; Niu, Y.; Shen, C. The Role of Hepatocyte Growth Factor in Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Induced Recovery in Spinal Cord Injured Rats. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 178.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, P.; Liu, T.; Xu, J.; Fan, Z.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, H. Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Is a Key Factor in the Homing of Transplanted Human MSCs to Sites of Spinal Cord Injury. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27724.

- Fu, X.; Liu, G.; Halim, A.; Ju, Y.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration and Tissue Repair. Cells 2019, 8, 784.

- Nitzsche, F.; Müller, C.; Lukomska, B.; Jolkkonen, J.; Deten, A.; Boltze, J. Concise Review: MSC Adhesion Cascade-Insights into Homing and Transendothelial Migration. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 1446–1460.

- Nam, D.; Park, A.; Dubon, M.J.; Yu, J.; Kim, W.; Son, Y.; Park, K.S. Coordinated Regulation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration by Various Chemotactic Stimuli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8561.

- Rahimi-Sherbaf, F.; Nadri, S.; Nadri, S.; Rahmani, A.; Oskoei, A.D. Placenta Mesenchymal Stem Cells Differentiation toward Neuronal-like Cells on Nanofibrous Scaffold. BioImpacts 2020, 10, 117–122.

- Zhang, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Lai, B.Q.; Qin, L.N.; Ding, Y.; Ruan, J.W.; Zhang, S.X.; Zeng, Y.S. Electro-Acupuncture Promotes the Survival and Differentiation of Transplanted Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Pre-Induced with Neurotrophin-3 and Retinoic Acid in Gelatin Sponge Scaffold after Rat Spinal Cord Transection. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2014, 10, 612–625.

- Wang, C.; Shi, D.; Song, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Calpain Inhibitor Attenuates ER Stress-Induced Apoptosis in Injured Spinal Cord after Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplantation. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 97, 15–25.

- Chung, H.J.; Chung, W.H.; Lee, J.H.; Chung, D.J.; Yang, W.J.; Lee, A.J.; Choi, C.B.; Chang, H.S.; Kim, D.H.; Suh, H.J.; et al. Expression of Neurotrophic Factors in Injured Spinal Cord after Transplantation of Human-Umbilical Cord Blood Stem Cells in Rats. J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 17, 97–102.

- Kim, Y.; Jo, S.H.; Kim, W.H.; Kweon, O.K. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Intravenously Injected Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Dogs with Acute Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 229.

- Phinney, D.G.; Pittenger, M.F. Concise Review: MSC-Derived Exosomes for Cell-Free Therapy. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 851–858.

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Péault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Perspective: Cell Biology to Clinical Progress. NPJ Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 22.

- Tahmasebi, F.; Barati, S. Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation on Spinal Cord Injury Patients. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 389, 373–384.

- Martins, L.F.; Costa, R.O.; Pedro, J.R.; Aguiar, P.; Serra, S.C.; Teixeira, F.G.; Sousa, N.; Salgado, A.J.; Almeida, R.D. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Secretome-Induced Axonal Outgrowth Is Mediated by BDNF. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4153.

- Chang, D.J.; Cho, H.Y.; Hwang, S.; Lee, N.; Choi, C.; Lee, H.; Hong, K.S.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; Shin, D.A.; et al. Therapeutic Effect of BDNF-Overexpressing Human Neural Stem Cells (F3.BDNF) in a Contusion Model of Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6970.

- Sieck, G.C.; Gransee, H.M.; Zhan, W.Z.; Mantilla, C.B. Neural Circuits: Acute Intrathecal BDNF Enhances Functional Recovery after Cervical Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. J. Neurophysiol. 2021, 125, 2158.

- Walker, M.J.; Xu, X.M. History of Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF) and Its Use for Spinal Cord Injury Repair. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 109.

- Pajer, K.; Bellák, T.; Nógrádi, A. Stem Cell Secretome for Spinal Cord Repair: Is It More than Just a Random Baseline Set of Factors? Cells 2021, 10, 3214.

- Sivak, W.N.; White, J.D.; Bliley, J.M.; Tien, L.W.; Liao, H.T.; Kaplan, D.L.; Marra, K.G. Delivery of Chondroitinase ABC and Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor from Silk Fibroin Conduits Enhances Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 11, 733–742.

- Kitamura, K.; Nagoshi, N.; Tsuji, O.; Matsumoto, M.; Okano, H.; Nakamura, M. Application of Hepatocyte Growth Factor for Acute Spinal Cord Injury: The Road from Basic Studies to Human Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1054.

- Agrelo, I.S.; Schira-Heinen, J.; Beyer, F.; Groh, J.; Bütermann, C.; Estrada, V.; Poschmann, G.; Bribian, A.; Jadasz, J.J.; Lopez-Mascaraque, L.; et al. Secretome Analysis of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Factors Fostering Oligodendroglial Differentiation of Neural Stem Cells In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4350.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, C.; Han, X.; Gu, X.; Zhou, S. Deciphering Glial Scar after Spinal Cord Injury. Burn. Trauma 2021, 9, tkab035.

- Kim, M.; Kim, K.H.; Song, S.U.; Yi, T.G.; Yoon, S.H.; Park, S.R.; Choi, B.H. Transplantation of Human Bone Marrow-Derived Clonal Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reduces Fibrotic Scar Formation in a Rat Spinal Cord Injury Model. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, e1034–e1045.

- Huang, F.; Gao, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Tai, C.; Liu, S.; Cui, Y.; Wang, B. Engineered Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor-Overexpressing Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve the Proliferation and Neuronal Differentiation of Endogenous Neural Stem Cells and Functional Recovery of Spinal Cord Injury by Activating the PI3K-Akt-GSK-3β Signaling Pathway. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 468.

- Pang, Q.M.; Chen, S.Y.; Xu, Q.J.; Fu, S.P.; Yang, Y.C.; Zou, W.H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Wan, W.H.; Peng, J.C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Scarring After Spinal Cord Injury: Therapeutic Roles of MSCs on Inflammation and Glial Scar. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 751021.

- Lv, C.; Zhang, T.; Li, K.; Gao, K. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improve Spinal Function of Spinal Cord Injury in Rats via TGF-Beta/Smads Signaling Pathway. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 3657–3663.

- Kim, C.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.T.; Yang, S.-R.; Chung, C.K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation Promotes Functional Recovery through MMP2/STAT3 Related Astrogliosis after Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Stem Cells 2019, 12, 331–339.

- Yang, Y.; Cao, T.T.; Tian, Z.M.; Gao, H.; Wen, H.Q.; Pang, M.; He, W.J.; Wang, N.X.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Subarachnoid Transplantation of Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Rodent Model with Subacute Incomplete Spinal Cord Injury: Preclinical Safety and Efficacy Study. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 395, 112184.

- Fu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Peng, J.; Ao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, G.; et al. Engrafted Peripheral Blood-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Locomotive Recovery in Adult Rats after Spinal Cord Injury. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3950.

- Cao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, C.; Xie, H.; Lu, H.; Hu, J. Local Delivery of USC-Derived Exosomes Harboring ANGPTL3 Enhances Spinal Cord Functional Recovery after Injury by Promoting Angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 20.

- Zhong, D.; Cao, Y.; Li, C.J.; Li, M.; Rong, Z.J.; Jiang, L.; Guo, Z.; Lu, H.B.; Hu, J.Z. Highlight Article: Neural Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Facilitate Cord Functional Recovery after Injury by Promoting. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 54.

- Al Mamun, A.; Monalisa, I.; Tul Kubra, K.; Akter, A.; Akter, J.; Sarker, T.; Munir, F.; Wu, Y.; Jia, C.; Afrin Taniya, M.; et al. Advances in Immunotherapy for the Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Immunobiology 2021, 226, 152033.

- Urdzíková, L.M.; Růžička, J.; LaBagnara, M.; Kárová, K.; Kubinová, Š.; Jiráková, K.; Murali, R.; Syková, E.; Jhanwar-Uniyal, M.; Jendelová, P. Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Modulate Inflammatory Cytokines after Spinal Cord Injury in Rat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11275–11293.

- Hakim, R.; Covacu, R.; Zachariadis, V.; Frostell, A.; Sankavaram, S.R.; Brundin, L.; Svensson, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplanted into Spinal Cord Injury Adopt Immune Cell-like Characteristics. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 115.

- Glennie, S.; Soeiro, I.; Dyson, P.J.; Lam, E.W.F.; Dazzi, F. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Induce Division Arrest Anergy of Activated T Cells. Blood 2005, 105, 2821–2827.

- Volarevic, V.; Gazdic, M.; Simovic Markovic, B.; Jovicic, N.; Djonov, V.; Arsenijevic, N. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Factors: Immuno-Modulatory Effects and Therapeutic Potential. Biofactors 2017, 43, 633–644.

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Tong, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, F.; Meng, Y.; Yuan, Z. Comparative Analysis of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Fetal-Bone Marrow, Adipose Tissue, and Warton’s Jelly as Sources of Cell Immunomodulatory Therapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 85.

- Wang, L.; Pei, S.; Han, L.; Guo, B.; Li, Y.; Duan, R.; Yao, Y.; Xue, B.; Chen, X.; Jia, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Reduce A1 Astrocytes via Downregulation of Phosphorylated NFκB P65 Subunit in Spinal Cord Injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 50, 1535–1559.

- An, N.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, S.; Wu, H.; Li, L.; Li, M. Mechanism of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Spinal Cord Injury Repair through Macrophage Polarization. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 41.

- Wu, L.-L.; Pan, X.-M.; Chen, H.-H.; Fu, X.-Y.; Jiang, J.; Ding, M.-X. Repairing and Analgesic Effects of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Transplantation in Mice with Spinal Cord Injury. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7650354.

- Wang, B.; Chang, M.; Zhang, R.; Wo, J.; Wu, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhong, C.; et al. Spinal Cord Injury Target-Immunotherapy with TNF-α Autoregulated and Feedback-Controlled Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Exosomes Remodelled by CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmid. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 133, 112624.

- Litak, J.; Szymoniuk, M.; Czyżewski, W.; Hoffman, Z.; Litak, J.; Sakwa, L.; Kamieniak, P. Metallic Implants Used in Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Materials 2022, 15, 3650.

- Litak, J.; Czyzewski, W.; Szymoniuk, M.; Pastuszak, B.; Litak, J.; Litak, G.; Grochowski, C.; Rahnama-Hezavah, M.; Kamieniak, P. Hydroxyapatite Use in Spine Surgery—Molecular and Clinical Aspect. Materials 2022, 15, 2906.

- Chung, H.; Park, S. Ghrelin Regulates Cell Cycle-Related Gene Expression in Cultured Hippocampal Neural Stem Cells. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230, 239–250.

- Glass, J.D.; Hertzberg, V.S.; Boulis, N.M.; Riley, J.; Federici, T.; Polak, M.; Bordeau, J.; Fournier, C.; Johe, K.; Hazel, T.; et al. Transplantation of Spinal Cord–Derived Neural Stem Cells for ALS. Neurology 2016, 87, 392–400.

- Todd, K.L.; Baker, K.L.; Eastman, M.B.; Kolling, F.W.; Trausch, A.G.; Nelson, C.E.; Conover, J.C. EphA4 Regulates Neuroblast and Astrocyte Organization in a Neurogenic Niche. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 3331–3341.

- Mardones, M.D.; Andaur, G.A.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Henriquez, J.F.; Salech, F.; Behrens, M.I.; Couve, A.; Inestrosa, N.C.; Varela-Nallar, L. Frizzled-1 Receptor Regulates Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Mol. Brain 2016, 9, 29.

- Meneghini, V.; Frati, G.; Sala, D.; De Cicco, S.; Luciani, M.; Cavazzin, C.; Paulis, M.; Mentzen, W.; Morena, F.; Giannelli, S.; et al. Generation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Bona Fide Neural Stem Cells for Ex Vivo Gene Therapy of Metachromatic Leukodystrophy. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 352–368.

- Morell, M.; Tsan, Y.; O’Shea, K.S. Inducible Expression of Noggin Selectively Expands Neural Progenitors in the Adult SVZ. Stem Cell Res. 2015, 14, 79–94.

- Wang, J.; Fu, X.; Zhang, D.; Yu, L.; Li, N.; Lu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, C.; et al. ChAT-Positive Neurons Participate in Subventricular Zone Neurogenesis after Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion in Mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 316, 145–151.

- Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Zheng, H.; Ho, J.; Chan, M.T.V.; Wu, W.K.K. Protective Roles of Melatonin in Central Nervous System Diseases by Regulation of Neural Stem Cells. Cell Prolif. 2017, 50, e12323.

- Zhang, M.; Lin, Y.H.; Sun, Y.J.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, J.; Liu, K.; Cao, N.; Li, K.; Huang, Y.; Ding, S. Pharmacological Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Neural Stem Cells by Signaling-Directed Transcriptional Activation. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 18, 653–667.

- Aggarwal, R.; Lu, J.; Pompili, V.J.; Das, H. Hematopoietic Stem Cells: Transcriptional Regulation, Ex Vivo Expansion and Clinical Application. Curr. Mol. Med. 2012, 12, 34–49.

- Frolov, A.A.; Bryukhovetskiy, A.S. Effects of Hematopoietic Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation to the Chronically Injured Human Spinal Cord Evaluated by Motor and Somatosensory Evoked Potentials Methods. Cell Transplant. 2012, 21, 49–55.

- Moghaddam, S.A.; Yousefi, B.; Sanooghi, D.; Faghihi, F.; Hayati Roodbari, N.; Bana, N.; Joghataei, M.T.; Pooyan, P.; Arjmand, B. Differentiation Potential of Human CD133 Positive Hematopoietic Stem Cells into Motor Neuron- like Cells, in Vitro. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2017, 86, 35–40.

- Xiong, L.L.; Liu, F.; Deng, S.K.; Liu, J.; Dan, Q.Q.; Zhang, P.; Zou, Y.; Xia, Q.J.; Wang, T.H. Transplantation of Hematopoietic Stem Cells Promotes Functional Improvement Associated with NT-3-MEK-1 Activation in Spinal Cord-Transected Rats. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 213.

- Takakura, N.; Watanabe, T.; Suenobu, S.; Yamada, Y.; Noda, T.; Ito, Y.; Satake, M.; Suda, T. A Role for Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Promoting Angiogenesis. Cell 2000, 102, 199–209.

- Liu, Y.; Kelamangalath, L.; Kim, H.; Han, S.B.; Tang, X.; Zhai, J.; Hong, J.W.; Lin, S.; Son, Y.J.; Smith, G.M. NT-3 Promotes Proprioceptive Axon Regeneration When Combined with Activation of the MTor Intrinsic Growth Pathway but Not with Reduction of Myelin Extrinsic Inhibitors. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 283, 73.

- Keefe, K.M.; Sheikh, I.S.; Smith, G.M. Targeting Neurotrophins to Specific Populations of Neurons: NGF, BDNF, and NT-3 and Their Relevance for Treatment of Spinal Cord Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 548.

- Liu, W.; Ma, Z.; Li, J.; Kang, X. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Therapeutic Opportunities and Challenges for Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 102.

- Liang, Y.; Wu, J.-H.; Zhu, J.-H.; Yang, H. Exosomes Secreted by Hypoxia-Pre-Conditioned Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reduce Neuronal Apoptosis in Rats with Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 701–714.

- Koprivec, S.; Novak, M.; Bernik, S.; Voga, M.; Mohorič, L.; Majdič, G. Treatment of Cranial Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Dogs Using a Combination of Tibial Tuberosity Advancement Procedure and Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells/Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells—A Pilot Study. Acta Vet. Hung. 2021, 68, 405–412.

- Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; He, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, N.; Rong, L.; Liu, B. Exosomes Derived from MiR-26a-Modified MSCs Promote Axonal Regeneration via the PTEN/AKT/MTOR Pathway Following Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 224.

- Herbert, F.J.; Bharathi, D.; Suresh, S.; David, E.; Kumar, S. Regenerative Potential of Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Spinal Cord Injury (SCI). Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 17, 280–293.

- Yousefifard, M.; Sarveazad, A.; Babahajian, A.; Rafiei Alavi, S.N.; Madani Neishaboori, A.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Hosseini, M.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Growth Factor Gene-Modified Cells in Spinal Cord Injury Recovery: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2022, 162, 150–162.e1.

- Lu, D.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.; Li, W.; Song, Y.; Feng, H.; Yu, W.; Ren, F.; Li, T.; et al. Development and Application of Three-Dimensional Bioprinting Scaffold in the Repair of Spinal Cord Injury. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2022, 19, 1113–1127.

- Zhou, Y.; Wen, L.L.; Li, Y.F.; Wu, K.M.; Duan, R.R.; Yao, Y.B.; Jing, L.J.; Gong, Z.; Teng, J.F.; Jia, Y.J. Exosomes Derived from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Protect the Injured Spinal Cord by Inhibiting Pericyte Pyroptosis. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 194–202.

- Tian, F.; Yang, J.; Xia, R. Exosomes Secreted from CircZFHX3-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells Repaired Spinal Cord Injury Through Mir-16-5p/IGF-1 in Mice. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 2076–2089.

- Shao, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhao, H.; Li, D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Exosomes Suppress Neuronal Cell Ferroptosis Via IncGm36569/MiR-5627-5p/FSP1 Axis in Acute Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 1127–1142.

- Kang, J.; Guo, Y. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Exosomes Promote Neurological Function Recovery in a Rat Spinal Cord Injury Model. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 1532–1540.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C.; Qiao, S.; Liu, T.; Qi, K.; Tong, D.; Li, C. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosome Attenuates Inflammasome-Related Pyroptosis via Delivering Circ_003564 to Improve the Recovery of Spinal Cord Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 6771–6789.

- Zhang, C.; Deng, R.; Zhang, G.; He, X.; Chen, H.; Chen, B.; Wan, L.; Kang, X. Therapeutic Effect of Exosomes Derived from Stem Cells in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review Based on Animal Studies. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 847444.

- Feng, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, P.P.; Wang, B. Gene-Modified Stem Cells for Spinal Cord Injury: A Promising Better Alternative Therapy. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 2662–2682.

- Zhang, B.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Yuan, H. NEP1-40-Overexpressing Neural Stem Cells Enhance Axon Regeneration by Inhibiting Nogo-A/NgR1 Signaling Pathway. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 2021, 18, 271–278.

- Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Liu, W. Motor Functional Recovery Efficacy of Scaffolds with Bone Marrow Stem Cells in Rat Spinal Cord Injury: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Spinal Cord 2022, 1–6.

- Haggerty, A.E.; Maldonado-Lasuncion, I.; Nitobe, Y.; Yamane, K.; Marlow, M.M.; You, H.; Zhang, C.; Cho, B.; Li, X.; Reddy, S.; et al. The Effects of the Combination of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Nanofiber-Hydrogel Composite on Repair of the Contused Spinal Cord. Cells 2022, 11, 1137.

- Xiao, Z.; Tang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Han, G.; Yin, N.; Li, X.; Chen, B.; Han, S.; Jiang, X.; Yun, C.; et al. Significant Improvement of Acute Complete Spinal Cord Injury Patients Diagnosed by a Combined Criteria Implanted with NeuroRegen Scaffolds and Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 907–915.

- Czyżewski, W.; Jachimczyk, J.; Hoffman, Z.; Szymoniuk, M.; Litak, J.; Maciejewski, M.; Kura, K.; Rola, R.; Torres, K. Low-Cost Cranioplasty-A Systematic Review of 3D Printing in Medicine. Materials 2022, 15, 4731.

- Rezmer, J.; Wasilewska, I.; Świątek, Ł. Use of 3d Printing Technology in the Treatment of Microtia and Other Outer Ear Deformities. J. Educ. Health Sport 2022, 12, 381–387.

- Rezmer, J.; Wasilewska, I.; Świątek, Ł. The Use of 3d Printing Technology in the Development of a Prosthetic Thumb. J. Educ. Health Sport 2022, 12, 405–409.

- Zarepour, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Gökmen, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Mostafavi, E. Spinal Cord Injury Management through the Combination of Stem Cells and Implantable 3D Bioprinted Platforms. Cells 2021, 10, 3189.

- Chen, C.; Zhao, M.L.; Zhang, R.K.; Lu, G.; Zhao, C.Y.; Fu, F.; Sun, H.T.; Zhang, S.; Tu, Y.; Li, X.H. Collagen/Heparin Sulfate Scaffolds Fabricated by a 3D Bioprinter Improved Mechanical Properties and Neurological Function after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2017, 105, 1324–1332.

- Sun, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhu, X.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, X.Y.; Yang, X.P.; An, X.W.; Liang, J.; Dong, H.J.; Jiang, W.; et al. 3D Printing Collagen/Chitosan Scaffold Ameliorated Axon Regeneration and Neurological Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2019, 107, 1898–1908.

- Li, X.H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.Y.; Xu, H.H.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.X.; Chen, X.Y.; et al. The Corticospinal Tract Structure of Collagen/Silk Fibroin Scaffold Implants Using 3D Printing Promotes Functional Recovery after Complete Spinal Cord Transection in Rats. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2021, 32, 31.

- Koffler, J.; Zhu, W.; Qu, X.; Platoshyn, O.; Dulin, J.N.; Brock, J.; Graham, L.; Lu, P.; Sakamoto, J.; Marsala, M.; et al. Biomimetic 3D-Printed Scaffolds for Spinal Cord Injury Repair. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 263–269.

- Zarepour, A.; Bal Öztürk, A.; Koyuncu Irmak, D.; Yaşayan, G.; Gökmen, A.; Karaöz, E.; Zarepour, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Mostafavi, E. Combination Therapy Using Nanomaterials and Stem Cells to Treat Spinal Cord Injuries. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2022, 177, 224–240.

- Somuncu, D.; Gartenberg, A.; Cho, W. Investigational Therapies for Gunshot Wounds to the Spine: A Narrative Review. Clin. Spine Surg. 2022, 35, 233–240.

- Hachmann, J.T.; Yousak, A.; Wallner, J.J.; Gad, P.N.; Edgerton, V.R.; Gorgey, A.S. Epidural Spinal Cord Stimulation as an Intervention for Motor Recovery after Motor Complete Spinal Cord Injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2021, 126, 1843–1859.

- Duan, R.; Qu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, T.; Huang, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X. Clinical Benefit of Rehabilitation Training in Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine 2021, 46, E398–E410.

- Hicks, A.L. Locomotor Training in People with Spinal Cord Injury: Is This Exercise? Spinal Cord 2021, 59, 9–16.

- Gaojian, T.; Dingfei, Q.; Linwei, L.; Xiaowei, W.; Zheng, Z.; Wei, L.; Tong, Z.; Benxiang, N.; Yanning, Q.; Wei, Z.; et al. Parthenolide Promotes the Repair of Spinal Cord Injury by Modulating M1/M2 Polarization via the NF-ΚB and STAT 1/3 Signaling Pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2020, 6, 97.

- Fang, H.; Yang, M.; Pan, Q.; Jin, H.L.; Li, H.F.; Wang, R.R.; Wang, Q.Y.; Zhang, J.P. MicroRNA-22-3p Alleviates Spinal Cord Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Modulating M2 Macrophage Polarization via IRF5. J. Neurochem. 2021, 156, 106–120.