Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Chemistry, Inorganic & Nuclear

In the extensive terrain of catalytic procedures for the synthesis of organic molecules, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) as heterogenous catalysts have been investigated in a variety of chemical processes, including Friedel–Crafts reactions, condensation reactions, oxidations, and coupling reactions, and utilized owing to their specific properties such as high porosity, tuneability, extraordinary catalytic activity, and recyclability.

- metal–organic frameworks (MOF)

- Cu-MOF

- catalyst

1. Introduction

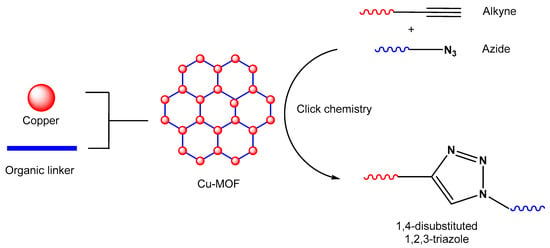

Click chemistry is one of the most robust and versatile methodologies currently known to researchers, capable of synthesizing large complex compounds from relatively smaller moieties [1,2]. Due to its advantageous features and facile pathway of synthesis, the methodology has received significant interest globally. Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Morten Meldal, and K. Barry Sharpless in 2022 were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their ground-breaking contribution, which was a big step in advancement. The advent of click chemistry has led to the discovery of nitrogen-rich azole heterocycles, which have been shown to be fascinating compounds with broad potential significantly with their pharmacological [3] and chemosensing [4] properties. ‘Click’ reactions, specifically Cu(I)-catalyzed cycloaddition involving a terminal alkyne and an organic azide to synthesize 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazole, have received a large amount of consideration in the fields of material science, polymer science, peptide chemistry [5], and synthetic organic chemistry over the past few decades. However, due to the fact that alkynes are poor 1,3-dipole acceptors, this reaction cannot proceed regioselectively without a suitable catalyst. Significantly, the presence of Cu(I), which forms bonds with terminal alkynes, greatly enhances the pace, selectivity, and overall efficiency of click reactions [6].

The catalysts tailored from transition metals have the potential to act as fabricators in the assemblage of supplementary intricate structures, yielding complex organic structures with relative ease. Several metal catalysts such as Ru, Ag, and Au with enhanced catalytic activity and selectivity have been described in the scientific literature [7,8]. In the past decade, the 1,3 dipolar cycloaddition reaction for the synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole has received considerable attention and has been investigated using a variety of different types of copper catalysts including Cu(II)-β-cyclodextrin [9], Cu(OAc)2 [10], Fe3O4@SiO2 picolinimidoamide–Cu(II) complex [11], Cu(II) porphyrin graphene [12], bromotris(triphenylphosphine)copper(I) [13], and Cu(II)-supported graphene quantum dots [14]. In spite of this, the majority of the copper catalysts that were discussed before had a number of significant drawbacks, including laborious and pricey preparation processes; the utilization of hazardous solvents and reagents; and, most critically, challenging procedures for catalyst separation [15]. Furthermore, the intensifying public concern for environmental protection has prompted scientists to look for more sustainable synthetic routes to overcome the challenges of recyclability of catalysts and switching to less hazardous solvents/chemicals. To anticipate the ease of the synthesis of 1,2,3-triazole derivatives, the area of organic synthesis has focused significantly on the creation of novel and effective Cu(I)-based MOFs catalysts (Figure 1). Over the past decade, scientists have made great strides to manufacture various MOFs and explore of their use in numerous scientific domains, including energy storages [16], medicinal technology [17], environmental pollution [18], sensing platforms, catalysis, photocatalysis [19], oxidation, hydrogenation [20], drug delivery [21,22], and bioimaging [23] due to their diverse active sites [24,25].

Figure 1. An illustration of MOF assembly and subsequent use in click chemistry.

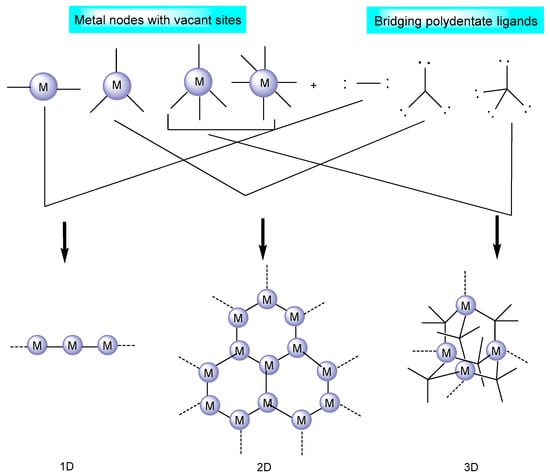

Metal–organic frameworks are strong hybrid emerging materials due to their amenable physical and chemical properties [26]; porous structure consisting of inorganic/supplementary building units (atoms, molecules, and ions of metals); and organic building blocks, known as linkers/bridging ligands (carboxylates, as well as anions such as phosphonate, sulfonate, and heterocyclic chemicals) [27], as shown in Figure 2. The long organic linkers are responsible for the high porosity and great storage capacity of MOFs [28]. In addition, they have the unique capacity to intentionally alter and adjust the form and function of their pores. Moreover, due to the remarkable adaptability of MOF structures, it is possible to synthesize catalytically active sites by employing defect engineering and linker modification strategies [29,30].

Figure 2. MOF structure based on the metal nodes and bridging ligands [31].

The coordination number, geometry, and functional assembly in MOFs play a dominant role in shaping the structure of the framework. MOFs have been found to display a wide range of supplementary binding unit (SBU) geometries, such as the octahedron, the trigonal matrix, the square paddlewheel, and the triangle, each of which has a different number of extension points [27]. As a general rule, a connecting ligand interacts with a metal ion that has several available reactive sites [31]. SBU connections and organic linkers control the ultimate topology of any given MOF such that infinitely stretched polymers or discretely closed oligomeric structures may emerge from a given system [32,33].

2. MOFs as Heterogenous Catalysts

The transition metal complexes can be utilized as homogenous catalysts due to their extraordinary catalytic action for a prevalent variety of organic reactions, showing regio- and chemoselectivity [34,35]. However, this recompense comes with some drawbacks, namely, the homogenous catalysts can be decomposed during the reaction process, making their recovery a challenging process [36]. The various techniques for heterogenizing a homogenous catalyst involve grafting of polymers, impregnation of solid carriers, introduction to zeolite cavities via the “ship in a bottle” method [37], and the formation of organized structured or non-organized structured mesoporous organic/inorganic hybrid systems [30].

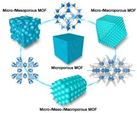

Researchers have primarily concentrated on heterogeneous catalysts, as opposed to homogeneous catalysts, due to the greater reusability and the high selectivity of the heterogenous catalyst [38]. In catalyst research, the gold standard followed currently is a combination of computational methods for predicting catalytic activity and novel synthesis methodologies for creating the appropriate organized frameworks, with constant, well-defined active sites that enable good selectivity while avoiding deactivation [39,40]. A large number of recently discovered heterogeneous catalysts are based on metal–organic frameworks, an attractive new field that uses metal ions as active sites in the generated crystal-like structure, metal complexes that were part of the organic linkers, or supported metal nanoparticles. The microporous MOF (microporous co-ordination polymer) generated as an outcome grounded on metal ion action at nodes or at the ligands emerges instantaneously as a counterpart of the homogeneous catalytic system [41]. Due to their potential use as contributing templates in the production of heterogenous catalysts, metal–organic frameworks have recently been a key area of research [42].

3. Physico-Chemical Properties of MOFs

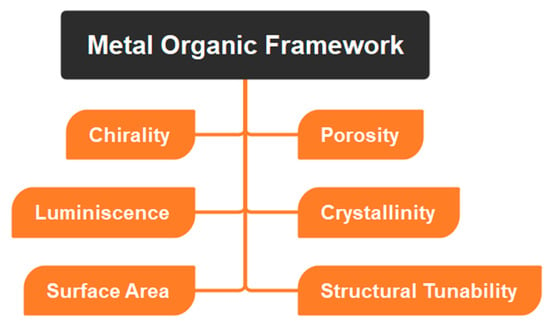

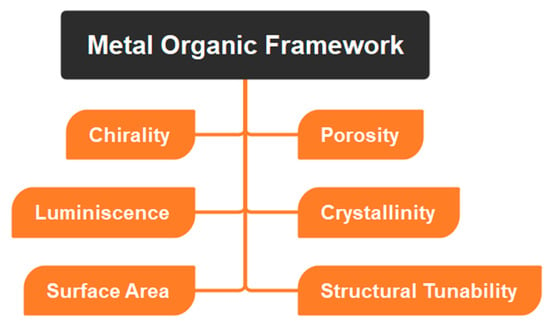

Since MOFs are composed of a metal ion bound to an organic linker chain, they have outstanding properties in terms of their size, porosity, etc. (Table 1, Figure 3), due to which MOFs can be used in a wide range of applications including catalysis, sensing, and drug delivery, among others. In addition, the MOFs may be changed via regulated integration in conjugation with one-of-a-kind and desirable functional materials, which can then impart the required characteristics onto the MOF structures [43,44]. Organic linkers with conjugated structures facilitate electron transfer between ligands and metals. For use as smart materials, MOFs with dynamic frameworks may undergo reversible structural changes that vastly increase their intended qualities.

Figure 3. Depicting physicochemical properties of MOFs.

Table 1. Physico-chemical properties of MOFs. * Reproduced from references with permission.

| Entry | Property | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Surface area |

|

| 2. | Porosity |

|

| 3. | Structure tunability and Luminescence |

|

| 4. | Chirality |

|

| 5. | Crystallinity |

|

4. Methods for the Synthesis of MOFs

Numerous techniques for the manufacture of MOFs have been documented in published works. Some examples of these techniques, which are included in the table below, are microwave-assisted synthesis [50], solvothermal synthesis, sonochemical synthesis, electrochemical synthesis [51], among others (Table 2). The choice of solvent is often influenced by a variety of characteristics, such as the redox potential, reactivity, stability constant, and solubility of the compound [52,53].

Table 2. General methods for synthesis of MOFs.

| Entry | Method | Description | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Electrochemical synthesis | Electrochemical synthesis involves the addition of metal ions into a reaction mixture consisting of organic linkers and electrolytes via anodic dissolution. The significant benefit of this technique is that the anions often found with metals in salts may be eliminated, resulting in very pure compounds, since less time and energy are needed for reactions to take place under more benign circumstances. | ZIF-8, HKUST-1, MIL-100 (Fe). | [51] |

| 2. | Microwave-assisted synthesis | The use of microwaves to irradiate the reaction mixture results in the creation of nanoscale MOF crystals. There are several benefits to this synthesis, including high efficiency, shorter reaction times, phase selectivity, morphological control, and particle size reduction. | [Cu3(btc)2(H2O)3], HKUST-1 | [50] |

| 3. | Mechanochemical synthesis | Mechanical forces are introduced to complete the chemical reaction. Mechanochemical synthesis has the benefit of not requiring the use of organic solvents, which may be carcinogenic, poisonous, and damaging to the environment. Metal oxides are often employed as precursors in this procedure rather than metal salts. | InOF-1, Cu3(BTC)2-MOF | [52,53] |

| 4. | Slow evaporation method | This conventional method for MOF preparation involves the use of suitable solvents to dissolve the precursor materials and later on slow evaporation of the solvent at an adequate temperature. The synthesis of MOFs using this approach is hindered by the insolubility of the chemicals. Accordingly, a combination of solvents may be utilised to improve solubility. | [Cu(2,3-pydc)(bpp)]·2. 5H2O, [Zn(2,3-pydc)(bpp)]·2. 5H2O |

[50] |

| 5. | Solvothermal synthesis | The reaction between the organic linker and metal ion takes place in a suitable solvent at a temperature above the boiling point of the solvent used. The primary benefit of this technique is that the relatively greater yield can be obtained. | Zn2(bpabdc)2(DMF)2(H2O)n, [Cu(tdc) (H2O)]n.n(DMA) |

[54,55] |

| 6. | Sonochemical synthesis | The solution mixture was subjected to ultrasonic radiations (20 kHz–10 MHz) to synthesize MOF with novel morphologies. The sonochemical technique allows for the rapid production of MOFs with a tiny crystal size in a very short reaction time. This approach has the benefits of being fast, cheap, repeatable, and eco-friendly. | HKUST-1, TMU-7, [Zn3(btc)2] | [56] |

5. MOFs as Catalysts for Innumerable Reactions

MOFs are becoming an integral part of the research society since they can be utilized as a low-cost heterogeneous catalyst in many different chemical processes [57]. This can be attributed to MOFs having large peripheral areas, size, shape, enantioselectivity, persistent porosity, and multifunctional ligands, with these being some of the interesting and modifiable features of MOFs [45]. There are several benefits of using MOFs as heterogeneous catalysts, including improved catalytic reactivity, flexibility, and facile tunability [52]. However, the use of MOFs is unfavorable for reactions that need extreme conditions because of their limited chemical and thermal stability [58]. Some of the many organic processes for which MOFs were utilized as catalysts or catalyst support include Friedel–Crafts reactions [59]; Knoevenagel condensation [60]; aldol condensation [61]; oxidation [51,62]; and coupling reactions [63,64,65].

Nguyen et al. described a solvothermal acylation process using IRMOF-8 for the Friedel–Crafts reaction, wherein 2,6-naphthalenedicarboxylic acid and zinc nitrate tetrahydrate are dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) for the synthesis of IRMOF-8. Moreover, a high yield of the product was achieved when the catalyst was employed in the reaction and was recovered successfully [59]. Similarly, MOF-5 was synthesized by Phan et al.—1,4-benzene dicarboxylic acid and zinc nitrate hexahydrate were combined in dimethylformamide (DMF) under solvothermal conditions to perform a Friedel–Crafts benzylation of toluene [66]. Gascon and teammates produced MOF with non-coordinated sites with an aniline-like amino group for Knoevenagel condensation with 100% selectivity. Xamena and colleagues studied the catalytic activity of IRMOF-3 and MOF-5 on the Knoevenagel condensation reaction [67]. The alkene oxidation of α-pinene and cyclohexene in a solvent-free environment was investigated by Kholdeeva et al. using MOFs (Fe-MIL-101 and Cr-MIL-10), and the allylic oxidation products were produced. Both Cr-MIL-101 and Fe-MIL-101 exhibited selectivity, with Cr-MIL-101 favoring the formation of α,β-unsaturated ketones, and Fe-MIL-101 forming 2-cyclohexen-1-ol as the desired product [51]. Under ideal circumstances, both catalysts demonstrated improved reusability. Torbina et al. determined the catalytic activity of chromium-based MOFs as a heterogenous catalyst for the oxidation reaction of propylene glycol with tert-butyl hydroperoxide [68]. In another example, Phan et al. employed the very porous metal–organic framework MOF-199 as a heterogeneous catalyst for the Ullmann reaction between phenols and aryl iodides to generate diaryl ethers. After six hours at 120 °C, the product yield was 82%. It was shown that the MOF-199 catalyst may be used several times without significantly losing its catalytic efficiency [69]. Several MOFs are used to catalyze the different reactions reported (Table 3). From this perspective, we focused on a few noteworthy instances that provide a balanced comparison to currently available copper-based MOFs over other MOFs to catalyze a wide variety of reactions.

Table 3. Several reactions catalyzed by MOF-based catalysts.

| Entry | Reaction Catalyzed | MOF Type | Metal in MOF | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Friedel–Crafts reaction | HPW@Zr-BTC | Zirconium | [70] |

| Cu-MOF-74 | Copper | [71] | ||

| Urea containing 2D MOF | Copper | [72] | ||

| 4. | Suzuki coupling | Cu-BDC MOF | Copper | [63] |

| 5. | Heck coupling | Pd(II)-porphyrinic MOF | Palladium | [73] |

| 6. | Suzuki–Miyaura coupling | NPC-Pd MOF | Palladium | [74] |

| 7. | Knoevenagel condensation | Al-MIL-101-NH2 | Aluminium | [75] |

| 8. | Aldol condensation | Basolite F300 | Iron | [61] |

| 9. | CuAAC reaction | Fe3O4@HKUST-1 | Copper | [76] |

6. Reactions Catalyzed by Cu-Tailored MOFs

Cu-MOFs have gained a great deal of popularity in the area of study as a result of their high catalytic activity, a wealth of resources, and ease of synthesis, all of which are facilitated by the excessive natural abundance of copper. Copper-containing catalysts provide a promising route for activating starting materials while maintaining reaction selectivity under tunable conditions, allowing for the generation of complex scaffolds from easily accessible building pieces [77,78]. A few of the reaction methodologies that are promoted by Cu(I) scaffolds are CuAAC, oxidation, coupling reactions, and Friedel craft acylation reactions, among others.

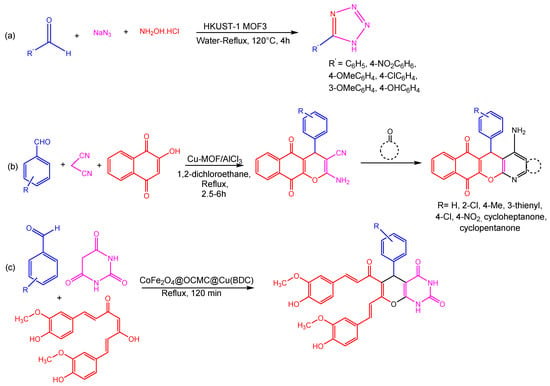

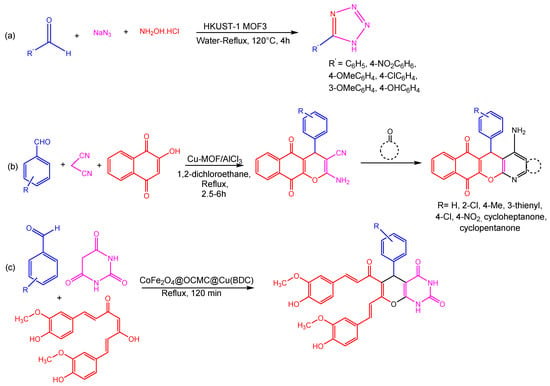

Maleki et al. employed the hydrothermal synthesis of Cu-MOF, presenting an effective and environmentally friendly technique of synthesizing tetrazole derivatives using Cu-MOF as a catalyst due to the high crystallinity and purity of HKUST-1 (Cu-MOF) (Figure 4). The structure’s face-centered cubic symmetry can be ascribed to the detail that three-dimeric copper wheels are covalently bonded to each BTC ligand. However, two copper atoms are octahedrally bonded to eight oxygen atoms. As a consequence of activation of the carbonyl and ethoxy groups during synthesis, Cu-MOF demonstrated good catalytic activity in three- and four-component processes involving aldehydes, amines, triethyl orthoformate, -keto-esters, and 2-cyano-guanidine [79]. Using aromatic aldehydes, malononitrile, 2-hydroxynaphthalene-1,4-dione, and cycloketone in a one-pot domino four-component reaction using a copper-based MOF as a heterogeneous catalyst and aluminum chloride as a Lewis acid, Taheri and co-workers examined the synthesis of tacrine derivatives. The reaction for the synthesis of MOF was completed at room temperature in the presence of a Cu(II) nitrate trihydrate and 1,4-benzenedioic acid in DMF. The use of Cu-MOF as the Lewis acid catalyst might facilitate the production of pyranic intermediates, which would then be followed by the Friedlander quinoline reaction being supplemented with AlCl3 in order to produce the desired products. In addition to higher yields, utilizing Cu-MOF as a heterogeneous catalyst for the production of the required products (Figure 4) also eliminates the need for a tremendous separation procedure for pyranic intermediates [80].

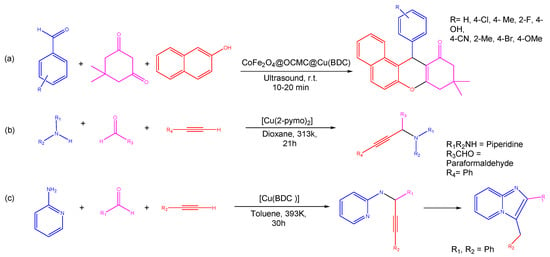

Ghasemzadeh et al. reported a condensation process between curcumin, aromatic aldehydes, and barbituric acid, used to efficiently synthesize novel pyrano [2,3-d] pyrimidine2,4-diones in a single step. The magnetic CoFe2O4@OCMC@Cu(BDC) showed superior catalytic activity in the generation of heterocyclic compounds (Figure 4) and had a remarkable degree of reusability through at least six cycles. The CoFe2O4@OCMC@Cu(BDC) catalyst may play a crucial role in promoting the reactions with high efficiency due to its abundance of Lewis acid sites (Co2+, Fe3+, and Cu2+) [81]. Moreover, a green three-component reaction carried between aldehydes, dimedone, and aryl amines/2-naphthol/urea to produce a wide range of substituted xanthene derivatives catalyzed by CoFe2O4@OCMC@Cu(BDC) MOF is reported by Ghasemzadeh and Ghaffarian. A metal–organic framework was shown to have a flower-like shape with surface area, total pore volume, and average pore diameters of 64,933 m2g−1, 0.186 cm3g−1, and 11.46 nm, respectively. This approach had several benefits, including good yields, clean and ecologically friendly settings, minimal catalyst loading, simple catalyst separation, and a short reaction time [82].

Three-component coupling and cyclization processes for the synthesis of propargylamines, indoles, and imidazopyridines were developed by Corma et al. via copper-containing MOF [Cu(2-pymo)2]. These crystal structures show that copper ions interact with adsorption substrates more efficiently attributable to a highly deformable, three-dimensional sodalite-like framework consisting of two Cu2+ ions attached to each heterocyclic ligand (pyrimidine, imidazole, or benzene). The MOFs possessed this characteristic, making them superior and more active than conventional N-heterocyclic copper coordination complexes. Using a three-component coupling process of amines, aldehydes, and alkynes catalyzed by [Cu(2-pymo)2], the propargylamine derivatives were synthesized with good yield and selectivity. On the other hand, the [Cu(BDC)] catalyst performed admirably in the 5-exo-dig cyclization of 2-aminopyiridine, aldehydes, and terminal alkynes to produce imidazopyridines (Figure 5) [79].

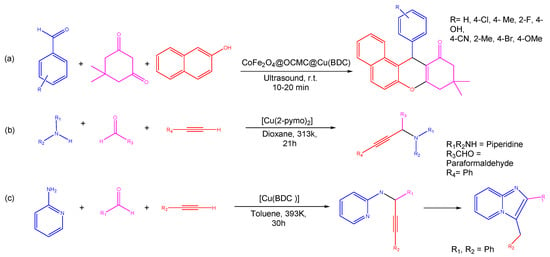

Figure 4. Different reactions catalyzed by Cu-MOFs (a) formation tetrazole from HKUST-1 MOF3 (b) three component coupling and cyclization reaction using Cu-MOF (c) single step three component coupling and cyclization reaction using CoFe2O4@OCMC@Cu(BDC) [82].

Figure 5. Schematic representation of the synthesis of (a) xanthene, (b) propargylamines, and (c) imidazopyridines using various copper MOFs as the catalysts [79].

The use of copper-tailored metal–organic frameworks has attracted a large amount of interest in a wide variety of processes such as condensation reactions, coupling reaction, and oxidation, but especially in click reactions [83]. It can be concluded that the reactions catalyzed by Cu-MOFs are significantly more versatile and robust than other metal catalysts, as well as the fact that Cu-MOFs have high recyclability, as depicted in Table 4. Furthermore, Cu(I) may coordinate with both hard and soft donor ligands in its coordination sphere, facilitating interactions between ligands of varying compositions [84,85].

Table 4. Comparison of Cu-based MOF over other catalysts used to catalyze an alkyne azide cycloaddition reaction.

| Entry | Catalyst | Metal | Reaction Conditions | Solvent | Recyclability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cu(INA)2-MOF | Cu(I) | 1.5 h, 80 °C | solvent free | 5 times | [86] |

| 2. | [Cu(CPA)(BDC)]n | Cu(I) | 7 h, 90 °C | H2O-MeOH (1:4) | 4 times | [60] |

| 3. | Cu2(BDC)2(DABCO) | Cu(I) | 45 min, 60 °C | ethanol | 5 times | [87] |

| 4. | CuI | Cu(I) | rt | no solvent | NA | [84] |

| 5. | CuBr(PPh3)3] | Cu(I) | 60 °C, 5 h | THF/TEA | NA | [88] |

| 6. | sf-CuS | Cu(I) | rt, 30 min | H2O | NA | [89] |

| 7. | AgN(CN)2 | Ag(I) | rt | DIPEAH 2O/ethylene glycol |

NA | [90] |

| 8. | ZnEt2 | Zn(II) | rt, 18 h | THF | NA | [91] |

| 9. | Au(RD32) | Au(III) | 60 °C, H2O | EtN3 | NA | [92] |

| 10. | RuH2(CO)(PPh3)3 | Ru(II) | 80 °C, 2 h | PTC, H2O | NA | [93] |

| 11. | Pd@PR | Pd(0) | 8–12 h, 100 ℃ | DMF | NA | [94] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/catal13010130

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!