The human endometrium has a complex cellular composition that is capable of promoting cyclic regeneration, where endometrial stem cells play a critical role. Menstrual blood-derived stem cells (MenSC) were first discovered in 2007 and described as exhibiting mesenchymal stem cell properties, setting them in the spotlight for endometriosis research. The stem cell theory for endometriosis pathogenesis, supported by the consensual mechanism of retrograde menstruation, highlights the recognized importance that MenSC have gained by potentially being directly related to the genesis, development and maintenance of ectopic endometriotic lesions.

1. MenSC in Patients with Endometriosis vs. Patients without Endometriosis

MenSC from patients with endometriosis (E-MenSC) display different morphologic, phenotypic, and functional characteristics when compared to MenSC from women without endometriosis (NE-MenSC).

With respect to morphology, NE-MenSC have a characteristic fibroblast-like spindle shape, whereas E-MenSC are described as being less stretched and elongated. Sahraei et al., through treatment with a conditioned medium derived from NE-MenSC, observed morphologic changes in E-MenSC, which acquired a more elongated, spindle-shaped morphology. In addition, as shown by Nikoo et al., E-MenSC form small colonies when grown in 3D cultures, which are absent in NE-MenSC cultures [

7,

8,

16,

19].

Concerning the differences in CD marker expression profiles, both E-MenSC and NE-MenSC were considered positive for CD9, CD10 and CD29 by Nikoo et al., although their expression was significantly higher in E-MenSC that in NE-MenSC. In contrast, Sahraei et al. found that CD9 and CD29 expression was significantly lower in E-MenSC, while CD10 was highly expressed. Moreover, after treatment with NE-MenSC-derived conditioned medium, CD10 expression decreased significantly in E-MenSCs, providing the CD10 surface marker with an important role in the diagnosis of endometriosis [

16,

20].

E-MenSC have been shown to possess higher proliferation and invasion capacities when compared with NE-MenSC. However, no differences were observed regarding their adhesion ability in Sharaei et al.’s research. Nevertheless, it is worth noting Nikoo et al.’s findings of higher CD29 expression levels in E-MenSC, which suggest that these cells might support attachment to the peritoneum. On the other hand, E-MenSC have shown a higher migratory capacity, shown by higher mRNA expression levels of the MMP-2 and MMP-9 genes in these cells when compared to NE-MenSC [

7,

8,

21,

22].

The apoptosis rate in the endometrial cells of women with endometriosis is decreased, suggesting that the survival rate of cells that reach the peritoneal cavity is higher in patients with progressive endometriosis. Sharaei et al.’s results suggest that the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio is significantly lower in E-MenSC than in NE-MenSC, which has been shown to have an important association with apoptosis, thus confirming the decreased apoptosis seen in endometriosis stromal cells [

7,

8,

21,

22].

Angiogenesis plays an essential role in the establishment and growth of endometriotic lesions, regardless of apoptosis. Likewise, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), considered as one of the most active angiogenic factors, is highly involved in both physiological and pathological angiogenesis. In endometriotic implants, growth factors, hormones, cytokines, and hypoxia stimulate the production of VEGF, which is secreted by the ectopic endometrium and peritoneal macrophages. In accordance, Sharaei et al. observed a high level of VEGF expression in E-MenSC [

7,

8,

21,

22].

There is accumulating evidence suggesting that a set of immune response-related malfunctions plays a key role in the development and progression of endometriosis. E-MenSC are considered to have greater potential in directing inflammatory responses. Regarding immunomodulation functions, Nikoo et al. first demonstrated that E-MenSC were different from NE-MenSC, exhibiting a higher expression of enzymes such as IDO1 and COX-2, while higher levels of FOXP3—a transcription factor involved in the development and function of regulatory T-cells—were found in E-MenSC which is. In addition, Sharaei et al. provided evidence that E-MenSC exhibit increased expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-1b, IL-6, and IL-8, secreted by peritoneal macrophages and ectopic endometriotic lesions, and the decreased expression of TNF-α, which might be another factor contributing to a proinflammatory peritoneal microenvironment. In addition, the expression of the transcription factor NF-κβis also higher in E-MenSC, promoting inflammation, invasion, angiogenesis, and cell proliferation in endometriotic lesions, as well as in the peritoneal macrophages of patients with endometriosis [

7,

8,

21,

22].

In endometriotic lesions, the inherent inflammation and estrogen exposure form a positive feedback loop, increasing the expression of aromatase and COX-2 and local estrogen production. Hence, it comes as no surprise that the expression of the estrogen gene in E-MenSC was found to be significantly higher than that in NE-MenSC [

7,

8,

21,

22].

There has been an overall attempt to understand the role of stemness-related genes in endometriosis. The increased expression of stemness-related markers in endometriotic tissue suggests that it can promote cell survival and self-renewal. A higher mRNA expression of NANOG, OCT-4, and SOX-2 genes, as well as miR-200b-3p upregulation, have also been observed in E-MenSC [

7,

8,

21,

22].

Penariol et al. were the first to apply multi-omics approaches in MenSC evaluation [

9]. Among the differentially expressed genes and proteins studied, the genes ATF3, ID1, ID3, FOSB, SNAI1, NR4A1, EGR1, LAMC3, and ZFP36 and the proteins COL1A1, COL6A2, and NID2 were considered to be overexpressed in E-MenSC when compared to NE-MenSC, unlike the downregulation of the MT2A and TYMP proteins seen in E-MenSC. These findings are consistent with the previously mentioned MenSC characteristics that result in the increased cell proliferation, stemness, and accentuated mesenchymal–epithelial transition process observed in endometriosis [

9] (

Table 1).

Table 1. Differences in MenSC observed between patients without endometriosis vs. patients with endometriosis.

| Characteristics |

NE-MenSC |

E-MenSC |

References |

| Morphology |

Fibroblast-like spindle shape |

Less stretched and elongated |

[8,20] |

| Surface Markers Expression |

| CD9 |

+ |

+/− |

[8,20] |

| CD10 |

+ |

++ |

[8,20] |

| CD29 |

+ |

+/− |

[8,20] |

| Proliferation capacity |

+ |

++ |

[8] |

| Invasive capacity |

+ |

++ |

[8] |

| Adhesion capacity |

+ |

+ |

[7,8] |

| Angiogenesis |

| VEGF |

+ |

++ |

[7,8] |

| Migratory capacity |

| MMP-2 |

+ |

++ |

[7,8,21,22] |

| MMP-9 |

+ |

++ |

[7,8,21,22] |

| Apoptosis |

++ |

+ |

[7,8] |

| Bax/Bcl-2 ratio |

++ |

+ |

[7] |

| Immunomodulation |

| IDO1 |

+ |

++ |

[8] |

| COX-2 |

+ |

++ |

[7,8,15,20] |

| FOXP3 |

++ |

+ |

[8] |

| IL-1β |

+ |

++ |

[7,15,20] |

| TNF-α |

++ |

+ |

[20] |

| IL-6 |

+ |

++ |

[7,15] |

| IL-8 |

+ |

++ |

[7,15] |

| NF-κβ |

+ |

++ |

[7] |

| Stemness-related genes |

| NANOG |

+ |

++ |

[7,8,21,22] |

| OCT-4 |

+ |

++ |

[7,8,21,22] |

| SOX-2 |

+ |

++ |

[7,8,21,22] |

| miR-200b-3p |

+ |

++ |

[22] |

| Differentially expressed genes |

| ATF3 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| ID1 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| ID3 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| FOSB |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| SNAI1 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| NR4A1 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| EGR1 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| LAMC3 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| ZFP36 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| Differentially expressed proteins |

| COL1A1 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| COL6A2 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| NID2 |

+ |

++ |

[9] |

| MT2A |

++ |

+ |

[9] |

| TYMP |

++ |

+ |

[9] |

2. MenSC-Based Early Diagnosis

Patients with endometriosis often experience a delay from the onset of symptoms to a definitive diagnosis, which can be up to 11 years. Consequently, a delay in treatment also occurs, potentially resulting in disease progression and increased severity. Based on the previously reported evidence in the literature, it is clear that MenSC are key to the early diagnosis of endometriosis in the future, with an enormous potential to shift this paradigm [

7,

8,

17,

21,

22].

As mentioned earlier, MenSC from patients with endometriosis differ from those of patients without endometriosis with respect to their morphology, phenotype, and mechanisms of action. Taking all this together, in combination with the fact that menstrual blood is an easily obtained, renewable, inexpensive, and non-invasive source of MenSC, these cells could be used as promising targets for the early diagnosis of endometriosis [

7,

8,

17,

21,

22].

These findings pave the way for novel multi-omics approaches to evaluate differences in MenSC between healthy individuals and patients with endometriosis. Therefore, it will be possible to optimize the combination of potential biomarkers, especially genes and proteins, and develop non-invasive diagnostic strategies. On the other hand, MenSC might also be helpful in predicting the risk of developing endometriosis in the future for healthy women [

7,

8,

17,

21,

22].

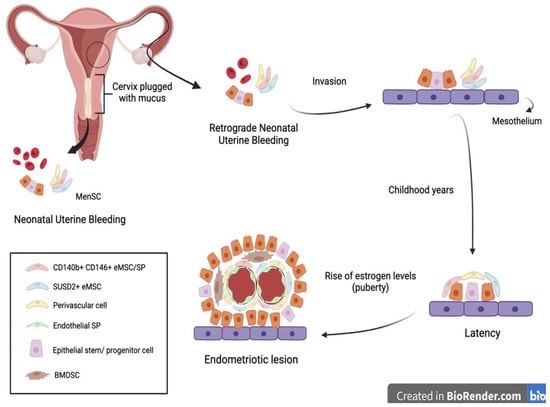

Another interesting approach to the early diagnosis of endometriosis was suggested by Cousins et al. and is related to neonatal uterine bleeding (NUB) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. In some neonates, the withdrawal of maternal progesterone causes a shedding of the endometrium causing neonatal uterine bleeding. Similar to menstruation, this blood contains epithelial stem cells and MenSC. The passage of these fragments through the vagina can be obstructed by the presence of a cervix plugged with mucus. Therefore, it is hypothesized that the fragments follow a retrograde route through the fallopian tubes and invade the mesothelium. There, they remain latent during childhood until the rise of estrogen levels during puberty, at which point they are activated and form an endometriotic lesion [

6]. BMDSC—bone marrow-derived stem cells; SP— side population.

At birth, neonates suffer from menstrual bleeding due to the shedding of the decidual endometrium following the sudden decline in maternal hormones [

6]. Their relatively long cervix, being functionally blocked with thick mucus, suggests that retrograde NUB may occur. It is hypothesized that fetal endometrial stem cells have the potential to gain access to the neonatal pelvic cavity, invading the mesothelium and remaining dormant until the rise of estrogen levels at puberty [

6].

3. MenSC-Based Therapies

The appeal of MenSC-based therapies mainly relates to the regular and non-invasive way that these cells can be obtained from menstrual blood. There is an undeniable therapeutic potential in MenSC as they exhibit the ability to migrate into injury sites, differentiate into distinct cell lineages, secrete soluble factors, and regulate immune responses, much like bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells [

16,

17].

As previously mentioned, their high proliferation rate allied with the stable genetic characteristics of MenSC, as well as their apparent pluripotency, make these cells promising candidates in stem cell therapy for inflammation and immune-related diseases. The aforementioned capacity of MenSC to differentiate into various cell types, confirms that these stem cells may exhibit unexpected therapeutic properties in the treatment of a variety of diseases in regenerative medicine. In fact, the therapeutic potential of MenSC has already been established for various diseases in pre-clinical research. Despite all these possible applications, MenSC could play a key role in the treatment of endometriosis given their major involvement in its pathogenesis [

16,

17].

By comparing the morphology, expression of surface markers, cell proliferation, invasion, adhesion, and immunomodulatory abilities of E-MenSC and NE-MenSC, the results of Sahraei et al. and Nikoo et al. clearly highlight the presumed role of MenSC in improving endometriosis. In addition, the increased expression of IDO1, COX-2, IFN-γ, IL-10, and MCP-1 and the decreased levels of FOXP3 observed in the co-culture of E-MenSC and peripheral blood mononuclear cells also supports this therapeutical potential [

4,

8,

9,

14,

17].

Regarding patient safety, the procedures for menstrual blood sample collection and MenSC isolation must be performed under aseptic conditions in agreement with the good manufacturing practice standards.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines11010039