Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

骨膜蛋白(由Postn基因编码)于1993年首次从小鼠成骨细胞系中发现,这是一种不含跨膜结构域的分泌分子,最初被称为成骨细胞特异性因子-2(OSF-2)。

- periostin

- variants

- non-neoplastic diseases

- roles

- biomarker

- drug

1. Introduction

Periostin (encoded by the Postn gene) was first recognized in 1993 from a mouse osteoblastic cell line, a secreted molecule containing no transmembrane domain, and was initially known as osteoblast-specific factor-2(OSF-2) [1]. It was renamed periostin in 1999 due to its preferential expression in the periosteum and periodontal ligament in adult mice reported by Horiuchi et al. Periostin used as a regulator promotes the adhesion and differentiation of osteoblasts [2].

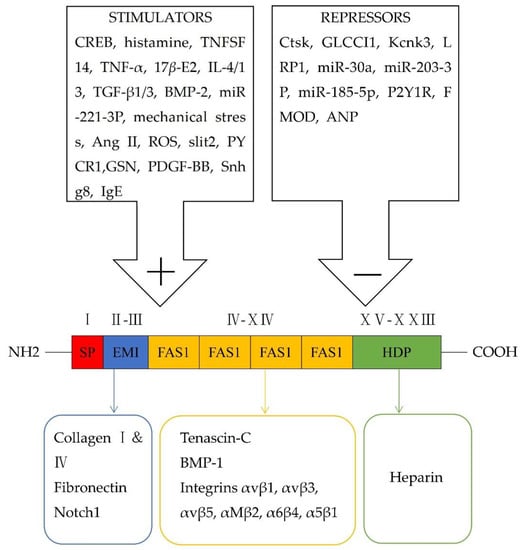

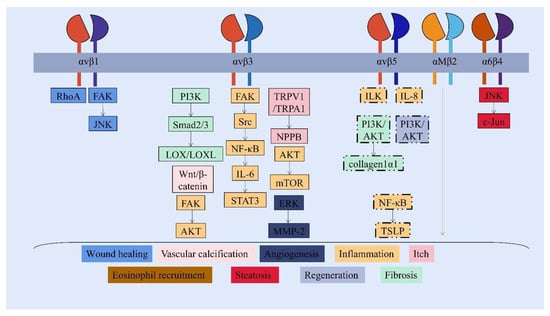

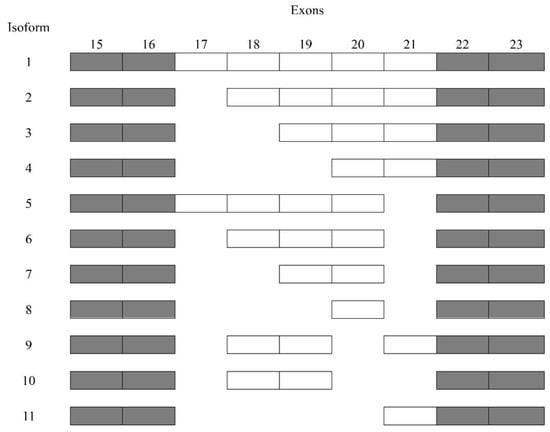

At approximately 90 kDa, periostin as an N-glycoprotein contains 23 exons exhibiting an NH2-terminal secretory signal peptide, accompanied by a highly conserved cysteine-rich EMI domain, which engages in the formation of multimers through cysteine disulfide bonds [3,4], four consecutive and homologous tandem Fasciclin I (FAS1) domains binding to integrins (αvβ1, αvβ3, αvβ5, αMβ2, α6β4, α5β1) and a COOH-terminal hydrophilic domain as an alternatively spliced region consisting of exons 15–23 (Figure 1) [5,6,7,8,9]. Periostin-integrin interactions lead to the activation of signaling pathways (Table 1; Figure 2). Apart from interacting with integrin receptors, it also binds other ECM proteins, for example, collagens, fibronectin, tenascin C, or heparin [4,10]. Periostin can form 11 splice variants (Figure 3). The expression pattern of periostin splicing variants has been reported in cerebral ischemia, asthma, MI, IPF, retinal ischemia, pIBD, joint, and serum (Table 2). Comparability of mouse and human periostin amino acid is 89.2% overall and 90.1% in a mature condition. Mouse and human periostin are respectively located on chromosome 3 and chromosome 13q.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of modular structural domains of periostin and its interaction with different receptors, as well as its stimulators and repressors.

Figure 2. Periostin-integrins interaction and activation of downstream signaling pathways. The FAS1 domain interacts with integrin receptors to activate different and overlapping signaling pathways, which modulate the progression of non-neoplastic diseases under pathological status. (Shared signaling pathways of integrin αv are shown in the box with a dotted line.)

Figure 3. Sequencing of periostin splice variants.

Table 1. Expression (upregulation ↑ or downregulation ↓) and roles of periostin, the periostin-involved signaling pathways, therapies based on periostin, and potential disease biomarkers in disease progression.

| Tissues/ Diseases |

Expression of Periostin |

Roles of Periostin |

Reference | Periostin- Involved Downstream Signaling Pathways |

Reference | Therapies Based on Periostin |

Reference | Potential Disease Biomarkers |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBI and cerebral ischemia | ↑ | BBB disruption | [11] | p38/ERK/MMP-9 | [11] | IAXO-102 Clarithromycin |

[12] [13] |

Serum periostin |

[14] |

| Ocular diseases | ↑ | Inflammation | [15] | Betamethasone; tacrolimus | [16] | Tear periostin | [17] | ||

| Tissue remodeling |

[18] | Serum periostin |

[19] | ||||||

| CRS and AR | ↑ | Inflammation | [20,21] | Omalizumab; mepolizumab; methylprednisolone; doxycycline | [22] | Serum periostin |

[23] | ||

| Tissue remodeling |

[21,24] | Src/AKT/mTOR | [24] | ||||||

| Protective role | [25] | Dupilumab | [26] | NLF periostin | [27] | ||||

| GCs | [28] | ||||||||

| AH | [29] | ||||||||

| AG-Ex | [30] | ||||||||

| Periodontitis | ↑ | Tissue remodeling |

[31] | GCF periostin | [32,33] | ||||

| Wound healing | [31] | β1/FAK/JNK; β1/RhoA | [31] | ||||||

| Bone formation | [34,35] | Saliva periostin | [33] | ||||||

| AD | ↑ | Inflammation | [36] | αv/NF-κB/TSLP; NF-κB/IL-6 | [36] | Dupilumab | [26] | ||

| Itch | [36] | αvβ3/TRPV1/TRPA1/NPPB; TSLP/TSLPR/JAK/STAT | [36] | ||||||

| Epidermal barrier malfunction | [37] | IL-24/STAT3 | [37] | Cinnamaldehyde | [38] | ||||

| Scleroderma | ↑ | Skin fibrosis | [39] | αv/PI3K/AKT/collagen1α1 | [39] | Crenolanib | [40] | Serum periostin |

[40] |

| EE | ↑ | Inflammation | [41] | αM | [41] | Dupilumab | [26] | Serum periostin |

[42] |

| Asthma | ↑ | Inflammation | [43] | Tralokinumab; dupilumab | [44,45] | Serum periostin |

[46] | ||

| Tissue remodeling |

[47] | Omalizumab | [48] | Plasma periostin |

[49] | ||||

| Hydroprednisone | [50] | Saliva periostin | [49] | ||||||

| Protective roles | [51,52] | Clarithromycin | [53] | EBC periostin | [54] | ||||

| Sputum periostin |

[55] | ||||||||

| Cardiovascular diseases (MI, heart failure, VHD, hypertension, and vascular calcification) | ↑ | Inflammation | [56] | Periostin/NLRP3/caspase-1 | [56] | Valsartan | [57] | Plasma periostin |

[58] |

| Tissue remodeling |

[59,60,61,62,63,64] | ||||||||

| Wound healing | [59,65] | Simvastatin | [63] | ||||||

| Cardiomyocytes apoptosis | [66] | ||||||||

| Myocardial regeneration |

[5,67,68] | αvβ1/αvβ3/αvβ5/PI3K/Akt; TNF-α/NF-κB; PI3K/AKT/cyclin D1 | [5,67,68] | Resveratrol | [69] | ||||

| Angiogenesis | [5] | ||||||||

| Vascular calcification | [70,71] | Crenolanib | [40] | ||||||

| Lung diseases (PF, EP, COVID-19, and PH) | ↑ | Inflammation | [72,73] | Serum monomeric periostin |

[74] | ||||

| Tissue remodeling |

[72,75,76,77] | EBC periostin | [74] | ||||||

| Angiogenesis | [78] | BALF periostin | [79,80] | ||||||

| Liver disease | ↑ | Liver steatosis | [81,82,83] | α6β4/JNK/c-Jun | [83] | Serum periostin |

[84] | ||

| Hepatic fibrosis | [82,85] | αvβ3/PI3K/Smad2/3/LOX/LOXL | [85] | ||||||

| Liver regeneration and angiogenesis |

[86] | ||||||||

| CKD | ↑ | Inflammation | [87,88] | αv/ILK; β3/FAK/AKT; αVβ3/AKT/mTOR | [5,88,89] | Losartan | [90] | Urine periostin | [91] |

| Renal fibrosis | [87,92,93] | FAK/p38/ERK; p38 MAPK | [92,93] | ||||||

| Vascular calcification |

[94] | αvβ3/Wnt/β-catenin | [94] | ||||||

| Renal repair | [95] | ||||||||

| Renal malfunction |

[96] | Serum periostin |

[97] | ||||||

| IBD | ↑ | Inflammation | [98] | NF-κB; αv/IL-8 | [98] | Plasma periostin |

[99] | ||

| Serum periostin |

[100] | ||||||||

| Osteoarthrosis (RA, OA, AS, osteoporosis, DDH, and IVD D) |

↓ in RA and osteoporosis | Bone formation | [101,102,103] | Inhibition of sclerostin/LRP5/Wnt, β-catenin; Wnt/β-catenin; ILK/Akt/GSK-3β; | [101,102,103] | Serum periostin |

[104] | ||

| ↑ in OA, AS, DDH, and IVDD | Inflammation | [105,106,107,108] | NF-κB/IL-6/8; Wnt/β-catenin/MMP-13/ADAMTS4; DDR1/Akt/Wnt/β-catenin/MMP-13; αvβ3/FAK/Src/NF-κB/IL-6/STAT3 | [105,106,107,108] | SF periostin | [109] | |||

| K-Postn | [110] | ||||||||

Table 2. The expression and roles of periostin isoforms in tissues/diseases.

| Tissues/Diseases | Certain Periostin Variants Expressed in Tissues/Diseases |

Roles of the Periostin Variants | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebral ischemia | Isoform 2 | Isoform 2 Minimizing the area of cerebral infarction via phosphorylation of Akt |

[111] |

| Asthma | Isoforms 6, 7, and 8 | Isoform 8 Promoting the eosinophil adhesion under IL-5 stimulation αMβ2] |

[112,113] |

| MI | Isoforms 1, 2, 5, and 6 | Isoform 1 Decreasing the attachment of fibroblasts and myocytes as well as facilitating myocytes death leading to ventricular dilation and tissue remodeling Isoform 6 Contributing to the migration of activated fibroblasts and healing of impaired tissue via the αv/FAK/AKT signaling pathway |

[114] |

| IPF | All periostin variants lacking exon 21 | - | [115] |

| Retinal ischemia | Isoforms 1, 2, and 5 | Isoforms 1, 2, and 5 Promoting preretinal pathological NV |

[116] |

| pIBD | Isoforms 2, 6, 7, and 8 | - | [99] |

| Joint | Articular chondrocytes highly expressed isoforms1 and 5, and anterior cruciate ligament(ACL) progenitor cells overexpressed isoforms 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 | - | [117] |

| Serum | At least five isoforms, including 1 or 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | At least five isoforms, including 1 or 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Forming complex with IgA |

[118] |

Periostin is commonly overexpressed in human tissues during pathological processes. Periostin, as a matricellular protein and an ECM protein, exerts different roles in tissue development and progression of diseases, including brain injury, ocular diseases, chronic rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis, dental diseases, atopic dermatitis, scleroderma, eosinophilic esophagitis, asthma, cardiac diseases, lung diseases, liver diseases, chronic kidney diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and osteoarthrosis. In a normal physiological situation, periostin is beneficial in mediating teeth development, maintaining the integrity of periodontal ligament (PDL) in postnatal teeth enamel formation, and mediating bone remodeling after orthodontic movement [119,120]; periostin promotes migration of mesenchymal cells in an αvβ3- and β1-based Rho/PI3K signaling mechanism during valve maturation [10]. Besides, during pathogenesis, the roles of periostin are more extensive, including tissue remodeling, fibrosis, inflammation, wound healing, repair, angiogenesis, tissue regeneration, bone formation, barrier, and vascular calcification; this makes it different from other ECM proteins.

Periostin assists in modulating the ECM network [9]. Periostin/BMP-1/LOX cascade assisted in collagen cross-linking [121]. During abnormal scar formation, periostin stimulated the secretion of TGF-β1 via the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs), yielding a vicious circle [122].

2. Early Brain Injury (EBI) and Cerebral Ischemia

The periostin was upregulated in neurons and capillary endothelial cells in the cerebral cortex at 24 h post-subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and initiated BBB disruption, possibly via p38/ERK/MMP-9 signaling pathways and induction of tenascin-C [11].

Following transient cerebral ischemia, isoform 2 minimized the area of cerebral infarction displaying a neuroprotective role with phosphorylation of Akt [111]. Greater serum periostin levels were related to a larger cerebral infarction area and more serious neurological defects at 6-28 days following ischemia [14]. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) selective blockade-IAXO-102 and clarithromycin inhibited BBB disruption and periostin expression [12,13].

3. Cardiovascular Diseases

3.1. Myocardial Infarction (MI)

Ang II evidently increased periostin through Ras/p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)/CREB and ERK/TGF-β1 pathways in myocytes and fibroblasts [123]. Detection of human tissue specimens reflected prominently high periostin expression in ischemic and reperfused tissue, as well as no expression in healthy myocardium [59]. The lineage analyses of mice verified that periostin-expressing CFs mainly derived from a mass of TCF21 cells [124]. After MI, TGF-β1, mechanical pressure, and Cyclic AMP response element-binding protein 1 (CREB) stimulated cardiac fibroblasts, thereby augmenting ECM deposition, development of collagenous scar and cardiac remodeling, and release of periostin [125]. TGF-β1 upregulated periostin levels in CFs and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) employing Smad signaling pathways [126,127]. Periostin showed minimal levels under miR-203-3p-binding circumstances restricting cardiomyocytes apoptosis. However, the complex of periostin, miR-203-3p, and small nucleolar RNA host gene 8 (Snhg8) mediated neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs) apoptosis after hypoxia-treated NMCMs, contributing to acute myocardial infarction [66]. Treatment of MI with cardiac mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) marked by Nestin demonstrated a greater effect on cardiac healing than bone marrow-derived MSCs (NesbmMSCs), which results from part involvement of periostin-induced M2 macrophage polarization [65]. In a rat MI model, Yoshiaki Taniyama et al. discovered four periostin isoforms, including isoforms 1, 2, 5, and 6. Isoform 1 decreased the attachment of fibroblasts and myocytes as well as facilitated myocyte death, leading to ventricular dilation and tissue remodeling. Blockade of exon 17 as prior target assists in protesting cardiac remodeling, diminishing fibrosis, ameliorating ejection fraction, and cardiac function eight weeks after MI [114]. Isoform 6 can mediate the migration of activated fibroblasts and the healing of impaired tissue by αv/FAK/AKT cascade [59]. The inhibition of periostin by valsartan might have an improved effect on cardiac remodeling after MI [57].+

3.2. Cardiomyocyte Regeneration

Release of periostin facilitated cardiomyocyte regeneration and angiogenesis by interacting with αvβ1, αvβ3, or αvβ5 integrins on myocytes and vascular endothelial cells to activate the PI3K-Akt pathways after MI. The treatment of animals with periostin patches (lacking the N-terminal signal peptide and C-terminal region) not only perfected cardiac fraction and ejection fraction but also contained fibrosis after MI [5]. Periostin eased inflammation and induced reentry of the cardiomyocytes cycle via TNF-α/NF-κB signaling transduction in conjunction with a declining caspase 7 activity [67]. Periostin ablation hindered myocardial regeneration by suppressing the PI3K/AKT/cyclin D1 transmission [68]. Another work in a mouse model of overexpressed full-length periostin indicated that periostin did not speed up the DNA synthesis of cardiomyocytes [128]. Further studies are needed to clarify these issues.

3.3. Heart Failure

In diabetic rat hearts, periostin is noticeably overexpressed relative to healthy controls [79]. In the experimental autoimmune myocarditis (EAM) rats model, periostin was spotted in macrophages and fibroblasts. It elicited cardiac fibrosis, likely by recruiting immune cells [60]. A recent examination of atrial appendages from atrial fibrillation (AF) patients suggested a clear association between periostin levels of atrial tissues and deteriorated heart failure, as well as lessened ejection fraction [129]. MiR-30a and fibromodulin (FMOD) tempted the descent of periostin levels and the decrease of atrial fibrosis [61]. GSN, silencing P2Y1R, and slit2-Robo1 pathways inversely initiated periostin release, tempting fibrosis [62]. Periostin prompted pyroptosis by triggering the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI) [56].

Valsartan and simvastatin (SIM) hindered periostin expression and alleviated pathologic remodeling [63,79]. Targeting of diabetic animals with the antioxidant resveratrol limited myofibroblast activation and downregulated the expression of periostin via suppressing ERK/TGF-β signaling [69].

3.4. Valvular Heart Disease (VHD)

Periostin expression intensively goes up in valvular interstitial cells (VICs) of the mitral valve, compared to wild-type mice. The mitral valve biopsies of male patients going through prosthetic surgery detected a pronounced enhancement in periostin in the ventricular [130]. Besides, periostin was firmly upregulated in the infiltrated inflammatory cells and myofibroblasts within patients with atherosclerotic or rheumatic valves. Meanwhile, massive periostin in the valve leaflet brings about extensive production of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and MMP-9, leading to severe fibrosis in atherosclerotic and rheumatic VHD [64]. Periostin also prompted the osteogenic potential of aortic valve calcification [131].

3.5. Hypertension and Vascular Calcification

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) inhibited periostin expression in the VSMCs and cardiac fibroblasts [70], but oxidative stress contributes to periostin production [132]. The increase in periostin augmented the differentiation and migration of VSMCs [133].

In a hyperlipidemia-associated model of rats, periostin upregulation caused calcium deposits through the successive inhibition of p53 and SLC7A11 in VSMCs [71]. Additionally, plasma periostin levels were positively connected with the Agatston score in patients with coronary artery calcification (CAC). Periostin promoted glycolysis and mitochondrial malfunction as well as contained peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor γ(PPARγ) in VSMCs, thereby provoking arterial calcification [58].

4. Ocular Diseases

IL-13 obviously stimulated periostin in conjunctival fibroblasts and, to a much smaller extent, in conjunctival epithelial cells. The recruitment of eosinophils and Th2 cytokines expression, including CCL5, IL-4, and IL-13, were restricted in periostin-deleted AC mice [15]. The concentration of tear periostin is heavier among patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) relative to healthy controls. Tear periostin levels had an infinitely positive association with complications of AKC by acting on corneal or conjunctival epithelial cells [17]. Tear periostin was decreased by treating with tacrolimus or betamethasone along with ameliorative clinical traits in the majority of patients with AKC [16].

Periostin upregulation may assist in scleral remodeling in myopia [18]. It was also manifestly increased in the vitreous of patients with proliferative vitreoretinal diseases, such as proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy. It was colocalized with α-SMA and M2 macrophage markers in the retinal fibrovascular membrane (FVM). The inhibition of it decreased retinal FVM formation [134]. Another study of diabetic retinopathy patients uncovered a positive correlation between serum periostin with continuous retinopathy and FVM formation [19]. Expression levels of isoforms 1, 2, and 5 are increased when the preretinal pathological neovascularization (NV) reaches the peak; they may be specific periostin splice variants for preretinal pathological NV in retinal ischemia [116].

5. Dental Diseases

During early periodontitis, Wnt5a/CaMKII/Periostin axis mediated collagen and bone formation, maintaining periodontal stabilization [135]. Applying gingivectomy to a rat model presented that periostin promotes ECM generation, as well as increases the formation of fibronectin and collagen via β1/FAK (focal adhesion kinase)/JNK propagation during wound healing. Periostin is not related to myofibroblast differentiation accounting for lessened scar generation [31]. By introducing an excisional palatal model, periostin mRNA and protein expression were upregulated, and it is correlated with fibronectin generation, transition to myofibroblast, and attachment of macrophages to the wound region. Periostin modulated palatal healing via the integrinβ1/RhoA pathway [31].

IL-4 and IL-13 evidently stimulated periostin expression in the human PDL (hPDL). HPDL cells displayed increased proliferation and migration and no significant difference in the generation of inflammatory cytokines under periostin stimulation [34,136]. TNF-α/periostin/JNK promoted the adhesion and osteogenic differentiation competence of human periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) [34,35].

GCF periostin levels are degressive with the activity and severity of periodontal disease, suggesting its beneficial role in maintaining the function of normal periodontal tissue [32,33]. Salivary periostin levels are positively linked to gingival inflammation and aggressive periodontitis (AgP) severity [33].

6. Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS) and Allergic Rhinitis (AR)

Among patients of CRS with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP), expression of the periostin gene seemed to be notably upregulated in nasal polyps than in normal sinus mucosa [137]. Mi1on’ski et al. revealed upregulation of periostin in non-polyp and polyp tissue of patients with CRS compared with patients without CRS [138].

CRSwNP and AR were taken for Th2-dominant inflammatory diseases. Higher periostin levels were related to increased basement membrane thickness, subepithelial fibrosis, and eosinophilia among patients undergoing surgery for CRS [20]. Periostin-induced tissue remodeling by activating the Src/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and inducing myofibroblasts differentiation and expression of ECM or by enhancing the mRNA expression of MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, and MMP-9 in fibroblasts and MMP-9 in epithelial cells in CRS. Additionally, IgE enhanced the periostin expression by a cultured human mast cell line (LAD2 mast cells), thereby leading to epithelial cells secreting thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) by binding to integrin, in turn activating mast cells to produce IL-5 [24]. Glucocorticoids (GCs) eased CRS by restricting the increase of periostin [28]. Previous studies thought that tissue periostin expression has evident relation with IL-5 and IL-13 levels among patients with CRSwNP [139,140].

A controversial finding demonstrated that the complete absence of periostin might result in mast cell attachment and polyp-like signs in CRSwNP [25]. Serum periostin was higher in patients with CRS than in controls [141]. Periostin levels of nasal lavage fluids (NLF) might function as a reliable marker involved in CRS [27]. Application of omalizumab, mepolizumab, methylprednisolone, and doxycycline into CRSwNP subjects arrested periostin production and inflammatory responses. Doxycycline decreased nasal periostin levels (p = 0.084), leading to the less frequent onset of asthma and reduced relapse of nasal polyps [22].

In an ovalbumin-treated murine model of AR, periostin knockout mice appeared to have lesser eosinophils, lower nasal symptom scores, and minimal nasal remodeling than controls [21]. Serum periostin serves to estimate the clinical responses to sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) within house dust mite (HDM)-induced AR subjects [23]. Asarum heterotropoides (AH) and Angelica gigas extract (AG-Ex) interfered with periostin release in HNEpCs (human nasal epithelial cells) and alleviated AR symptoms [29,30]. The treatment of AR with nasal neurectomy pronouncedly reduced NLF periostin value [142].

7. Asthma

Allergic asthma is mostly a Th2-involved heterogeneous inflammation attended by eosinophilia, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and excessive mucus secretion from goblet cells. IL-13/IL-4 have been found to induce periostin expression in bronchial epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts. Periostin isoforms 6, 7, and 8 are evidently expressed in lung fibroblasts [112]. MiR-185-5p negatively modulates mRNA and protein expression of periostin within airway cells and sputum periostin concentration [143]. MiR-221-3p provoked airway eosinophilic inflammation by suppressing CXCL17 expression and subsequently upregulating CCL24, CCL26, and periostin expression in HDM-stimulated mice [144].

A previous investigation into the aspergillus fumigatus antigen-challenged mice model supported that periostin serves a beneficial role in protesting AHR, serum IgE levels, and outcome of peribronchial fibrosis by intensifying TGF-β-mediated Treg differentiation [51]. Besides, another mouse model revealed that periostin suppressed mucus production of goblet cells and increased airflow by checking the expression of Gob5 and Muc5ac [52]. The roles of periostin absence in goblet cell metaplasia (GCM) were involved in at least two pathological mechanisms: direct impacts on differentiation of airway epithelial cells to goblet cells and indirect influences by changing the number of DC-derived cytokines acting on T cells.

A study in HDM-challenged mice offered the opposite effect. Periostin-expressing dendritic cells (DCs) from HDM-challenged wild-type mice kept asthma-like features and IL-13 responses after transferring into periostin null mice [43]. Application of anti-periostin antibody OC-20 weakened the AHR, IgE response, IL-13 responses, and DNA synthesis of T cells incubated with periostin-positive DCs. Periostin-overexpressed epithelial cells manifested that release of TGF-β in epithelial cells is attributed to a signaling pathway involving periostin/MMP-2, MMP-9, resulting in collagen Ⅰ production of airway fibroblasts. The process fuels the matrix stiffening [47]. The crosstalk of periostin and TSLP is an exquisitely driving factor for asthma [145]. In asthma patients, Kanemitsu et al. concluded that the accumulation of periostin in bronchial subepithelium was manifestly linked to the descent of FEV1 [146]. Anti-αMβ2 (specifically to periostin isoforms 1 and 8) and anti-ADAM8 blockers contained adhesion and migration of IL-5-stimulated eosinophils into periostin [113,147,148].

Serum periostin is linked to type 2 biomarkers, including eosinophilia, IgE concentration, and the fraction of NO (FeNO) inhalation, IL-4, and TSLP [149]. High serum periostin levels in patients receiving corticosteroids had prominent relation with the decline of pulmonary function tests and the increase of airflow limitation [46]. Both plasma periostin and saliva periostin levels had the advantage of early diagnosis of asthma [49]. Exhaled breath condensate (EBC) periostin levels seemed to reflect the emergence of CRS in asthma [54]. Sputum periostin levels offer an accurate diagnosis of serious asthma with continuous airflow limitation compared with mild-to-moderate asthma [55].

Lebrikizumab as an anti-IL-13 antibody was available to improve the function of the lung [150]. Periostin levels were strikingly correlated positively with the efficacy of these drugs, which included anti-IL-13 Ab-tralokinumab and dupilumab (common receptor of IL-4 and IL-13) [44,45]. The addition of dupilumab lowers serum periostin expression in AD, asthma, CRSwNP, and EE [26]. In addition to this, the effective therapeutic response of anti-IgE Ab omalizumab in asthma patients was dependent on high serum periostin [48]. Both hydroprednisone therapy and glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1 (GLCCI1) overexpression repressed the airway remodeling in asthma mice model via suppressing IL-13/periostin/TGF-β1 axis [50]. Clarithromycin can alleviate asthma by arresting periostin generation [53].

8. Lung Diseases

8.1. Pulmonary Fibrosis (PF)

Periostin is overexpressed in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). It was produced by fibroblasts and promoted their proliferation [151,152]. Nance et al. proposed that periostin mRNA was relatively lacking exon 21 in IPF samples compared to controls [115]. The absence of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) prominently irritates the JNK/c-Jun/Fra-2 signaling pathway leading to the induction of α-SMA and periostin expression in human lung fibroblasts (hLF), tempting fibrosis of the lung [75]. Periostin furthered the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages or myofibroblasts differentiation, accelerating pulmonary fibrosis [72,76]. The crosstalk of TGF-β and periostin also participated in the process of PF [73]. Serum monomeric periostin and EBC periostin both served as possible biomarkers to monitor IPF progression [74]. Moreover, serum periostin was also linked to fibrogenesis in COVID-19 [153]. Periostin of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) might exaggerate the onset of eosinophilic pneumonia (EP), IPF, and COVID-19 [79,80]. The siRNA and antisense oligonucleotide targeting periostin, OC-20, and antibodies targeting αv integrin prevented lung fibrosis [151,154,155].

8.2. Pulmonary Hypertension (PH)

In ascending aortic constriction (AAC)-treated PH model, kcnk3-mutated rats presented greater expression of IL-6 and periostin in lung and heart as well as the lower extent of lung ctnnd1 mRNA levels, aggravating pulmonary and heart remodeling as well as lung vascular edema [77]. The feedback cycle between HIF-1α and periostin magnified PH by intensifying the proangiogenic role [78].

9. Atopic Dermatitis (AD)

Characteristics of AD include type 2 immune response, dermal fibrosis, barrier malfunction, and itch. Histamine and TNF superfamily member 14 (TNFSF14) upregulated periostin levels [156,157], which mediated the crosstalk of epithelial/mesenchymal. There exist two potential mechanisms to interpret it: first, IL-4/IL-13 tempts periostin secretion in fibroblasts. Periostin applies to keratinocytes via activating αv-mediated NF-κB signaling accompanied by the release of TSLP, which differentiates or stimulates DCs, developing a vicious cycle of type 2 inflammatory responses. Second, IL-1α and periostin are separately released by keratinocytes and fibroblasts, and their unity applies to fibroblasts by transducing the NF-κB pathway. Activated fibroblasts generate IL-6, contributing to the growth of keratinocytes. In addition, the cross-link of immune cells/non-immune cells with the help of periostin also accounted for the pathological mechanism of allergy. Periostin generated by fibroblasts amplifies adhesion, O2− emergence, and TGF-β release in eosinophils. Activated eosinophils, in turn, lead to periostin generation in fibroblasts. Another paper uncovered the crosstalk of epithelial/sensory neurons. i.e., keratinocytes-derived TSLP directly targets TRPA1 sensory neurons, irritating skin itch [36]. Signaling transmission of activating αvβ3/TRPV1/TRPA1/NPPB (natriuretic polypeptide B) in sensory neurons is involved in the periostin-mediated itch mechanism. The TSLP-periostin vicious loop also augmented inflammation and itch, creating ever-terrible circumstances: Keratinocytes secreted TSLP unlocking inflammatory response, and then TSLP back triggered the release of keratinocytes-derived periostin by means of TSLPR/JAK/STAT signaling propagation. In turn, periostin reciprocally stimulates the production of keratinocytes-derived TSLP. IL-13/STAT6/periostin/IL-24/STAT3 signaling transmission in keratinocytes sped up the inflammation process by incurring epidermal barrier malfunction [37].+

The concentration of serum periostin rests on the grade of clinical severity of AD. It is related to other type 2 biomarkers―LDH and eosinophils, but not with IgE. Thus, monitoring it is of great help for the diagnoses and therapies of AD patients [158]. The blocking antibodies directed toward αv delayed AD progression [159]. By introducing dupilumab drugs, clinical outcomes were improved, and serum periostin evidently decreased [160]. Antioxidant cinnamaldehyde stimulated the NRF2/HMOX1 pathway and alleviated IL-13 and TGF-β1 mediated production of ROS, subsequently downregulating periostin in dermal fibroblasts. It may benefit in treating systemic fibrotic diseases [38].

10. Scleroderma

Periostin was upregulated in the skin of patients with scleroderma. The bleomycin-treated periostin−/− mice showed reduced skin fibrosis followed by the descent of α-SMA myofibroblasts. However, recombinant mouse periostin resulted in the generation of collagen1α1 in myofibroblasts via the αv/PI3K/AKT signal axis [39]. Yamaguchi et al. discovered that periostin was colocalized with α-SMA myofibroblasts [161] and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 endothelial cells. Elevated serum periostin levels were associated with the severity of skin sclerosis. Crenolanib is an effective medication for diminishing skin and heart fibrosis by inhibiting periostin expression [40].+++

11. Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EE)

IL-13 and TGF-β stimulated periostin release in primary esophageal fibroblasts. Periostin was manifestly overproduced in the esophageal papillae and correlated positively with esophageal eosinophil amounts among patients with EE. The migration of eosinophils to the esophagus is due to the specific interaction of αM with periostin [41]. Elevated serum periostin levels were positively associated with IL-13 levels and may be used as a biomarker in EE in the presence of anti-IL-13 treatment [42].

12. Liver Diseases

In a mice model of dexamethasone (DEX)-treated fatty liver, DEX induced a higher degree of periostin expression in white adipose tissues, driving liver steatosis in a systemic organ-mediated fashion [81]. Periostin increased hepatic fibrosis and hepatic steatosis by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α(PPAR-α) expression [82]. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting periostin lowered hepatic steatosis in conjunction with reduced expression of α-SMA, collagen I, and other fibrotic markers and increased expression levels of PPAR-α. Another literature depicted that the periostin/α6β4/JNK/c-Jun prevented the binding of RORα to PPAR-α, suppressing PPAR-α expression and contributing to hepatosteatosis [83]. Periostin is mainly observed in activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Periostin tempted liver fibrosis by activating LOX and lysyl oxidase-like (LOXL) in chronic liver disease via the αvβ3/PI3K/Smad2/3 signaling pathway [85]. Periostin deletion devastated angiogenesis in the process of liver regeneration [86]. Serum periostin is forcefully correlated with higher nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [84].

13. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Periostin is overexpressed in a variety of kidney diseases. It is mainly presented in the glomerulus, renal arteries, tubular cells, and interstitial area. For healthy donors, periostin is found in the vascular pole of the glomerulus and around Bowman’s capsule. Some opposite evidence confirmed that periostin has no expression in healthy kidney specimens. Periostin upregulation contributed to the fibrosis of CKD disease by inducing the FAK/p38/ERK pathway and expression of collagen I [92]. Periostin strengthened fibrosis and apoptosis in tubular epithelial cells by activating the phosphorylated-p38 MAPK pathway, facilitated vascular calcification through αvβ3/Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and accelerated inflammatory reaction by activating the β3/FAK/AKT pathway under NF-κB medication or mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)-mediated inhibition of autophagy in CKD [87,88,93,94]. Additionally, periostin/αv/ILK (integrin-linked kinase) and periostin/αvβ3/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways both aggravated the growth of cyst epithelial cells in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) [5,89]. In contrast to the above reporter, periostin served beneficial roles in renal repair, such as driving the proliferation of tubular cells via binding to integrin-β1 as well as the polarization of macrophage embodying pro-reparative characteristic following acute kidney injury (AKI) [95].

In hypertensive nephropathy, periostin correlated positively with creatinine and proteinuria. Losartan deterred periostin synthesis leading to lower renal fibrosis [90]. In diabetic renal disease, elevated urine periostin content was accompanied by the emergence of albuminuria [162]. Moreover, serum periostin could estimate diabetic disease stages [97].

Periostin advanced the proliferation of mouse mesangial cells (MMCs) to augment renal malfunction in Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) [96]. Urine periostin concentration correlated with tissue fibrosis in biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy subjects [163]. During the progression of UUO, mechanical stress as an initiating signal increased periostin accumulation in collecting duct cells. Subsequently, periostin advanced the production of proinflammatory factor MCP-1 that mediated macrophage infiltration, and then TGF-β secreted by infiltrating cells induced periostin production and strengthened the phenotype change of tubular epithelial cells [92]. After 5/6 nephrectomy, periostin which was detected in the distal tubule (DT) epithelial cell, drove the expression of fibroblast-specific protein-1 (FSP-1) and MMP-9 in distal collecting tubular cells [91]. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) stimulated the PI3K/AKT/periostin signaling cascade, driving the expression of fibronectin and proliferation in MMCs in lupus nephritis [164].

14. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Periostin and αv integrin are more strongly presented in the colon tissues of UC (Ulcerative colitis) patients than in healthy colonic mucosa. Periostin accumulation occurred in pericryptal fibroblasts [165]. Introducing recombinant periostin elicits colitis in periostin-absence mice, and the blocking antibody specific to periostin obviously mitigates intestinal inflammatory disease. TNF-α stimulates the expression of periostin mRNA in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs). Periostin induced IL-8 expression and magnified NF-κB activity in IECs. Meanwhile, the combination of periostin with TNF-α synergistically reinforced IL-8 levels via interaction with integrin αv [98]. The pIBD patients presented elevated peri-cryptal staining compared to controls, but the expression pattern of periostin isoforms showed no significance. Thus, certain specific periostin isoforms and changes in periostin-binding molecule expression levels in the peri-cryptal ring might account for enhanced pericryptal periostin rings in pediatric IBD (pIBD) patients. Great plasma levels of the periostin during the period of pIBD remission may participate in mucosal healing and tissue repair [99]. Another literature on Crohn’s disease (CD) ascertained the cut-off levels of serum periostin in adult patients to serve to diagnose CD and forecast the activity status of CD [100].

15. Osteoarthrosis

15.1. Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

In a mouse model of mocking arthritis, periostin loss mice appeared to have a higher degree of inflammation. In RA remission, serum periostin embodied high extent of levels [104], increasing the risk of fragility fractures.

15.2. Osteoarthritis (OA)

Normal articular chondrocytes highly expressed isoforms 1 and 5, and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) progenitor cells overexpressed isoforms 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8. ACL progenitor cells that highly expressed total periostin, not isoform 1, showed higher cell adhesion than articular chondrocytes that expressed lower total periostin [117]. Mechanical pressure, as the primary reason, initiates and fuels inflammatory responses of OA. The cDNA array analysis revealed that periostin is at maximal levels in the cartilage of OA than controls. The periostin-positive signal was detected in chondrocytes, periphery matrices close to the degraded region, fibrotic cartilage, and tissue of subchondral bone. The application of periostin into isolated human chondrocytes might provoke a high expression of IL-6 and IL-8 accompanied by the sufficient expression of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-13, and nitric oxide synthase-2(NOS2) in an NF-κB-activated mechanism [105]. Periostin accelerated cartilage denaturation in Wnt/β-catenin/MMP-13/ADAMTS4- or discoidin domain receptor-1(DDR1)/Akt/Wnt/β-catenin/MMP-13-dependent mechanism [106]. It also had a contributory effect on MMP-2 and MMP-3 expression in OA synoviocytes. Synovial fluid (SF) periostin was positively associated with the progression of OA [109].

15.3. Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS)

Periostin was secreted by osteoblasts in AS. Serum periostin was higher under high inflammatory factors, disease severity, and low radiographic injury conditions [166].

15.4. Osteoporosis

Periostin lowers sclerostin levels, followed by the activation of the LRP5/Wnt/β-catenin cascade, boosting gene transcription within osteoblasts to induce bone formation [101]. In huRANKL-overexpressed mice, cathepsin K (Ctsk) limited bone formation and increased bone fragility by preventing periostin generation, which offers an underlying mechanism for osteoporosis in PMW [167]. The 17β-E2/periostin/Wnt/β-catenin pathway can enhance the osteogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) in ovariectomized (OVX) rats, thereby decreasing osteoporosis [102]. Periostin also reinforced the osteogenic competence of bone marrow skeletal stem cells in an ILK/Akt/GSK-3β-activated manner [103]. Serum periostin is related inversely to bone mineral density (BMD) in Chinese postmenopausal women (PMW) [168]. Cathepsin K-generated periostin (K-Postn) predominantly reflected fracture of Caucasian PMW with primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) [110].

15.5. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH)

In chondrocytes, periostin upregulated IL-6 and MMP-3 levels based on the integrin-FAK-Src-NF-κB pathway. Meanwhile, it limited the production of Col2a1 and Acan. Then, IL-6/STAT3/periostin and MMP-3, as a vicious feedback loop, augmented hip dislocation-induced acetabular cartilage denaturation [107].

15.6. Intervertebral Disc Degeneration (IVDD)

Periostin accelerated nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs) apoptosis and intervertebral disc denaturation via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [108].

16. Conclusions

Periostin exerts an integral role in the crosstalk between tumor cells and tumor microenvironments, cell and matrix, physiological function, and pathological function. Although the substantial data proved its significance in tissue remodeling, fibrosis, inflammation, wound healing, repair, and vascular calcification mediated by diverse signaling pathways, there were still a few works that determined its protective roles in ameliorating CRS and asthma, promoting the regeneration of myocardium and liver as well as renal repair, and maintaining periodontal stabilization, these discrepancies are most probably due to differences in animal models. In addition, different roles caused by disparate diseases are likely attributed to different locations, cell types that respond, and pathologic processes of these diseases. Periostin serves functions by diverse signaling pathways such as FAK, Src, NF-κB, p38, ERK, mTOR, JNK, PI3K, Akt, Smad2/3, MAPK, Wnt/β-catenin, to name just a few. Thus, the application of therapies based on periostin function is of great account and creates a favorable outlook for subsequent clinical studies.

It should be noted that loss of the αv integrin as a way of blocking periostin gives play to the majority of undesirable accidents such as prenatal death, colitis, wasting, and autoimmunity [169,170]. We still need to make significant efforts to boost the development of precision medicine through current knowledge and continuous explorations on exact and detailed mechanisms of periostin-involved diseases, despite the journey being full of challenges.

Furthermore, periostin exhibited the potential of acting as a clinically relevant and serviceable biomarker to aid in the diagnosis, speculate on the progression and activity of the disease, inform on prognosis, and direct choice for therapeutic approaches of disease. Periostin, as an attractive and available biomarker for inflammatory diseases, is presently garnering extensive attention. Nevertheless, it must be noticed that the flaw of periostin as a biomarker is that basal expression levels of serum periostin are held high in childhood until bone development halts [171]. Another issue is that periostin isoforms (1 or 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) and IgA form a complex in serum, which possibly influences the measuring of serum periostin [118].

Different tissues are characterized by heterogeneous expression profiles of periostin isoforms. Currently, the pathological roles of only several periostin isoforms have been displayed, and the functions of each encoded isoform have not been entirely exposed. Further exploration is needed to analyze the functional property of each coding isoform. Moreover, it is of great urgency to develop emerging drugs on the basis of the stimulators or inhibitors affecting periostin expression, periostin itself, the periostin-involved receptors and signaling pathways, or certain periostin isoforms-mediated channels.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Article collection and writing of the first draft were performed by L.Y., Y.C. and T.G. The manuscript was revised by K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers No. 81871258 to K.B.).

Data Availability Statement

All cited articles in the current study are available in the public database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| OSF-2 | Osteoblast-specific factor-2 |

| FAS1 | Fasciclin I |

| HDFs | Human dermal fibroblasts |

| PDL | Periodontal ligament |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| GCF | Gingival crevicular fluid |

| AgP | Aggressive periodontitis |

| CRS | Chronic rhinosinusitis |

| AR | Allergic rhinitis |

| CRSwNP | CRS with nasal polyposis |

| GCs | Glucocorticoids |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| TSTP | Thymic stromal lymphopoietin |

| NLF | Nasal lavage fluids |

| SLIT | Sublingual immunotherapy |

| AH | Asarum heterotropoides |

| HNEpCs | Human nasal epithelial cells |

| AG-Ex | Angelica gigas extract |

| CFs | Cardiac fibroblasts |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| CREB | Cyclic AMP response element-binding protein 1 |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

| LOX | Lysyl oxidase |

| BMP-1 | Bone morphogenic protein-1 |

| Snhg8 | Small nucleolar RNA host gene 8 |

| NMCMs | Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| EAM | Experimental autoimmune myocarditis |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| GSN | Gelsolin |

| FMOD | Fibromodulin |

| MIRI | Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury |

| SIM | Simvastatin |

| VHD | Valvular heart disease |

| VICs | Valvular interstitial cells |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| ANP | Atrial natriuretic peptide |

| AHR | Airway hyperresponsiveness |

| Th2 | T-helper type 2 |

| GCM | Goblet cell metaplasia |

| HDM | House dust mite |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| EBC | Exhaled breath condensate |

| GLCCI1 | Glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1 |

| EE | Eosinophilic esophagitis |

| AD | Atopic dermatitis |

| TNFSF14 | TNF superfamily member 14 |

| NPPB | Natriuretic polypeptide B |

| BP | Bullous pemphigoid |

| SD | Stasis dermatitis |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| pIBD | Pediatric IBD |

| IECs | Intestinal epithelial cells |

| PH | Pulmonary hypertension |

| AAC | Ascending aortic constriction |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| ACL | Anterior cruciate ligament |

| NOS2 | Nitric oxide synthase-2 |

| DDR1 | Discoidin domain receptor-1 |

| SF | Synovial fluid |

| AS | Ankylosing Spondylitis |

| Ctsk | Cathepsin K |

| BMSCs | Bone marrow stromal cells |

| OVX | Ovariectomized |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| PMW | Postmenopausal women |

| K-Postn | Cathepsin K-generated periostin |

| PHPT | Primary hyperparathyroidism |

| DDH | Developmental dysplasia of the hip |

| IVDD | Intervertebral disc degeneration |

| NPCs | Nucleus pulposus cells |

| AC | Atopic conjunctivitis |

| AKC | Atopic keratoconjunctivitis |

| FADS | Facial atopic dermatitis with scratching |

| PVR | Proliferative vitreoretinopathy |

| FVM | Fibrovascular membrane |

| NV | Neovascularization |

| IPF | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| LRP1 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 |

| hLF | Human lung fibroblasts |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| EP | Eosinophilic pneumonia |

| CAC | Coronary artery calcification |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor |

| EBI | Early Brain Injury |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| DEX | Dexamethasone |

| ASOs | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| HSCs | Hepatic stellate cells |

| LOXL | Lysyl oxidase-like |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| UIRI | Unilateral ischemia-reperfusion injury |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| mTORC1 | mTOR complex-1 |

| ILK | Integrin-linked kinase |

| ADPKD | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease |

| PA | Periostin-binding DNA aptamer |

| IFTA | Interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy |

| MCs | Mesangial cells |

| IgAN | Immunoglobulin A nephropathy |

| DT | Distal tubule |

| FSP-1 | Fibroblast specific protein-1 |

| RAAS | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| PDGF-BB | Platelet-derived growth factor-BB |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| MMCs | Mouse mesangial cells |

References

- Takeshita, S.; Kikuno, R.; Tezuka, K.; Amann, E. Osteoblast-specific factor 2: Cloning of a putative bone adhesion protein with homology with the insect protein fasciclin I. Biochem. J. 1993, 294, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, K.; Amizuka, N.; Takeshita, S.; Takamatsu, H.; Katsuura, M.; Ozawa, H.; Toyama, Y.; Bonewald, L.F.; Kudo, A. Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor beta. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1999, 14, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doliana, R.; Bot, S.; Bonaldo, P.; Colombatti, A. EMI, a novel cysteine-rich domain of EMILINs and other extracellular proteins, interacts with the gC1q domains and participates in multimerization. FEBS Lett. 2000, 484, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kii, I.; Nishiyama, T.; Li, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Saito, M.; Amizuka, N.; Kudo, A. Incorporation of tenascin-C into the extracellular matrix by periostin underlies an extracellular meshwork architecture. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 2028–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühn, B.; del Monte, F.; Hajjar, R.J.; Chang, Y.S.; Lebeche, D.; Arab, S.; Keating, M.T. Periostin induces proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac repair. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utispan, K.; Sonongbua, J.; Thuwajit, P.; Chau-In, S.; Pairojkul, C.; Wongkham, S.; Thuwajit, C. Periostin activates integrin α5β1 through a PI3K/AKT-dependent pathway in invasion of cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiao, Y.; Xiong, X.; Wang, E.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Pan, L.; Guan, Y.; et al. Periostin promotes liver steatosis and hypertriglyceridemia through downregulation of PPARα. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 3501–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, D.F.; Johansson, M.W.; Gillis, M.E.; Annis, D.S. Periostin and TGF-β-induced protein: Two peas in a pod? Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 50, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak-Wielgomas, K.; Kmiecik, A.; Dziegiel, P. Role of Periostin Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Periostin Silencing Inhibits the Migration and Invasion of Lung Cancer Cells via Regulation of MMP-2 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, R.A.; Moreno-Rodriguez, R.A.; Sugi, Y.; Hoffman, S.; Amos, J.; Hart, M.M.; Potts, J.D.; Goodwin, R.L.; Markwald, R.R. Periostin regulates atrioventricular valve maturation. Dev. Biol. 2008, 316, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kawakita, F.; Fujimoto, M.; Nakano, F.; Imanaka-Yoshida, K.; Yoshida, T.; Suzuki, H. Role of Periostin in Early Brain Injury After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Mice. Stroke 2017, 48, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, T.; Kawakita, F.; Nishikawa, H.; Nakano, F.; Liu, L.; Suzuki, H. Selective Toll-Like Receptor 4 Antagonists Prevent Acute Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamaru, H.; Kawakita, F.; Nishikawa, H.; Nakano, F.; Asada, R.; Suzuki, H. Clarithromycin Ameliorates Early Brain Injury After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage via Suppressing Periostin-Related Pathways in Mice. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1880–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosius, W.; Michalak, S.; Kazmierski, R.; Lukasik, M.; Andrzejewska, N.; Kozubski, W. The Association between Serum Matricellular Protein: Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine-Like 1 Levels and Ischemic Stroke Severity. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, 682–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asada, Y.; Okano, M.; Ishida, W.; Iwamoto, S.; Fukuda, K.; Hirakata, T.; Tada, N.; Fukushima, A.; Ebihara, N.; Kudo, A.; et al. Periostin deletion suppresses late-phase response in mouse experimental allergic conjunctivitis. Allergol. Int. 2019, 68, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunomura, S.; Kitajima, I.; Nanri, Y.; Kitajima, M.; Ejiri, N.; Lai, I.S.; Okada, N.; Izuhara, K. The FADS mouse: A novel mouse model of atopic keratoconjunctivitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, H.; Okada, N.; Matsumoto, K.; Fukagawa, K.; Igarashi, A.; Matsuda, A.; Ono, J.; Ohta, S.; Mukai, H.; Yoshikawa, M.; et al. The usefulness of measuring tear periostin for the diagnosis and management of ocular allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 459–467.e452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Shi, C.S. Dynamic changes of periostin and collagen I in the sclera during progressive myopia in guinea pigs. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2020, 83, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, A.; Senthilkumar, G.P.; Jayashree, K.; Ramesh Babu, K. Assessment of circulating fibrotic proteins (periostin and tenascin -C) In Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with and without retinopathy. Endocrine 2022, 76, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenezer, J.A.; Christensen, J.M.; Oliver, B.G.; Oliver, R.A.; Tjin, G.; Ho, J.; Habib, A.R.; Rimmer, J.; Sacks, R.; Harvey, R.J. Periostin as a marker of mucosal remodelling in chronic rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 2017, 55, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, D.G.; Khalmuratova, R.; Ahn, S.K.; Ha, Y.S.; Min, Y.G. Roles of periostin in symptom manifestation and airway remodeling in a murine model of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma. Immunol. Res. 2012, 4, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Schryver, E.; Derycke, L.; Calus, L.; Holtappels, G.; Hellings, P.W.; Van Zele, T.; Bachert, C.; Gevaert, P. The effect of systemic treatments on periostin expression reflects their interference with the eosinophilic inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology 2017, 55, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshino, M.; Akitsu, K.; Kubota, K.; Ohtawa, J. Serum Periostin as a Biomarker for Predicting Clinical Response to House Dust Mite Sublingual Immunotherapy in Allergic Rhinitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.; Wang, M.; Zhang, N.; Yu, P.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Bachert, C. Involvement of the extracellular matrix proteins periostin and tenascin C in nasal polyp remodeling by regulating the expression of MMPs. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2021, 11, e12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Jung, M.H.; Hur, D.G.; Lee, H.K.; Jeon, S.Y.; Kim, D.W. Periostin may play a protective role in the development of eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in a mouse model. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.D.; Harel, S.; Swanson, B.N.; Brian, W.; Chen, Z.; Rice, M.S.; Amin, N.; Ardeleanu, M.; Radin, A.; Shumel, B.; et al. Dupilumab suppresses type 2 inflammatory biomarkers across multiple atopic, allergic diseases. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.W.; Cha, J.; Han, S.; Chen, Y.; Gucek, M.; Cho, H.J.; Nakahira, K.; Choi, A.M.K.; Ryu, J.H.; Yoon, J.H. Apolipoprotein E and Periostin Are Potential Biomarkers of Nasal Mucosal Inflammation. A Parallel Approach of In Vitro and In Vivo Secretomes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.W.; Park, J.H.; Shin, J.M.; Lee, H.M. Glucocorticoids ameliorate periostin-induced tissue remodeling in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Jung, M.A.; Hwang, Y.H.; Pyun, B.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, D.H.; Ji, K.Y.; Kim, T. Anti-allergic effects of Asarum heterotropoides on an ovalbumin-induced allergic rhinitis murine model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, K.Y.; Jung, D.H.; Pyun, B.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, S.; Jung, M.A.; Song, K.H.; Kim, T. Angelica gigas extract ameliorates allergic rhinitis in an ovalbumin-induced mouse model by inhibiting Th2 cell activation. Phytomedicine 2021, 93, 153789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Nikoloudaki, G.E.; Michelsons, S.; Creber, K.; Hamilton, D.W. Fibronectin synthesis, but not α-smooth muscle expression, is regulated by periostin in gingival healing through FAK/JNK signaling. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balli, U.; Keles, Z.P.; Avci, B.; Guler, S.; Cetinkaya, B.O.; Keles, G.C. Assessment of periostin levels in serum and gingival crevicular fluid of patients with periodontal disease. J. Periodontal. Res. 2015, 50, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, C.A.; Köseoğlu, S.; Sağlam, M.; Pekbağrıyanık, T.; Savran, L. Gingival Crevicular Fluid and Salivary Periostin Levels in Non-Smoker Subjects With Chronic and Aggressive Periodontitis : Periostin Levels in Chronic and Aggressive Periodontitis. Inflammation 2016, 39, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padial-Molina, M.; Volk, S.L.; Rios, H.F. Periostin increases migration and proliferation of human periodontal ligament fibroblasts challenged by tumor necrosis factor -α and Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharides. J. Periodontal. Res. 2014, 49, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, P.; Chen, D.; Wu, Z.; Tang, C. Periostin promotes migration and osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament mesenchymal stem cells via the Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK) pathway under inflammatory conditions. Cell Prolif. 2017, 50, e12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.R.; Thé, L.; Batia, L.M.; Beattie, K.; Katibah, G.E.; McClain, S.P.; Pellegrino, M.; Estandian, D.M.; Bautista, D.M. The epithelial cell-derived atopic dermatitis cytokine TSLP activates neurons to induce itch. Cell 2013, 155, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitamura, Y.; Nunomura, S.; Nanri, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Masuoka, M.; Tsuji, G.; Nakahara, T.; Hashimoto-Hachiya, A.; Conway, S.J.; et al. The IL-13/periostin/IL-24 pathway causes epidermal barrier dysfunction in allergic skin inflammation. Allergy 2018, 73, 1881–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchi, H.; Yasumatsu, M.; Morino-Koga, S.; Mitoma, C.; Furue, M. Inhibition of aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling and induction of NRF2-mediated antioxidant activity by cinnamaldehyde in human keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 85, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Serada, S.; Fujimoto, M.; Terao, M.; Kotobuki, Y.; Kitaba, S.; Matsui, S.; Kudo, A.; Naka, T.; Murota, H.; et al. Periostin facilitates skin sclerosis via PI3K/Akt dependent mechanism in a mouse model of scleroderma. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Makino, T.; Stawski, L.; Mantero, J.C.; Lafyatis, R.; Simms, R.; Trojanowska, M. Blockade of PDGF Receptors by Crenolanib Has Therapeutic Effect in Patient Fibroblasts and in Preclinical Models of Systemic Sclerosis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalathas, P.; Farris, A.; Letner, D.; Deshpande, V.; Yajnik, V.; Shreffler, W.; Garber, J. Integrin αM activation and upregulation on esophageal eosinophils and periostin-mediated eosinophil survival in eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2018, 96, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellon, E.S.; Higgins, L.L.; Beitia, R.; Rusin, S.; Woosley, J.T.; Veerappan, R.; Selitsky, S.R.; Parker, J.S.; Genta, R.M.; Lash, R.H.; et al. Prospective assessment of serum periostin as a biomarker for diagnosis and monitoring of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, J.K.; Chen, Q.; Hong, J.Y.; Popova, A.P.; Lei, J.; Moore, B.B.; Hershenson, M.B. Periostin is required for maximal airways inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, A.; Edwards, M.; Nair, P.; Drew, S.; Vyas, A.; Sharma, R.; Marsden, P.A.; Wang, R.; Evans, D.J. Anti-interleukin-13 and anti-interleukin-4 agents versus placebo, anti-interleukin-5 or anti-immunoglobulin-E agents, for people with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, Cd012929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brightling, C.E.; Chanez, P.; Leigh, R.; O’Byrne, P.M.; Korn, S.; She, D.; May, R.D.; Streicher, K.; Ranade, K.; Piper, E. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2015, 3, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemitsu, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Izuhara, K.; Tohda, Y.; Kita, H.; Horiguchi, T.; Kuwabara, K.; Tomii, K.; Otsuka, K.; Fujimura, M.; et al. Increased periostin associates with greater airflow limitation in patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 305–312.e303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.S.; Yuan, S.; Innes, A.L.; Kerr, S.; Woodruff, P.G.; Hou, L.; Muller, S.J.; Fahy, J.V. Roles of epithelial cell-derived periostin in TGF-beta activation, collagen production, and collagen gel elasticity in asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14170–14175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 田尻;松本;贡,Y.;伊藤;桥本;伊豆原;铃川;太田;小野;太田;等。血清骨脂蛋白和游离 IgE 水平在评估重度哮喘患者对奥马珠单抗的反应中的效用。过敏 2016, 71, 1472–1479.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 密歇根州哈奇姆;新墨西哥州埃勒曼;拉玛克里希南;哈希姆;萨拉梅;马赫布布;阿尔·海亚利;哈尔瓦尼;哈穆迪;Hamid,Q.影响正确解释骨膜素水平作为哮喘发展生物标志物的混杂患者因素。J.哮喘。过敏 2020, 13, 23–37.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 荀琪;匡;杨秦;王文;糖皮质激素诱导的转录本1通过抑制IL-13 / 骨膜素/ TGF-β1信号传导抑制哮喘小鼠的气道重塑。国际免疫药理学。 2021, 97, 107637.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 戈登;西杜;王志东;伍德拉夫;袁淑;索伦;康威;黄霞;洛克斯利;法希,J.V.骨膜素和TGF-β在IgE介导的过敏和气道高反应性中的保护作用。临床过敏 2012, 42, 144–155.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 塞拉;姚文;阮;阿伊;图阿纳;阿尔菲尔德;斯奈德;泰珀;彼得拉奇,I.;康威;等。骨膜素调节过敏性气道炎症模型中的杯状细胞化生。J.免疫。 2011, 186, 4959–4966.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 小宫;太田;有马;小川;铃木;三田村;努诺村;南里;吉原;川口;等。克拉霉素可减弱IL-13诱导的人肺成纤维细胞中骨膜素的产生。呼吸。 2017, 18, 37.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 瓦尔金斯卡;马科斯卡,J.S.;帕韦乌奇克;皮乔塔-波兰奇克;库罗斯基;Kowalski,M.L.呼出呼吸冷凝物和哮喘患者血清中的Periostin:与上气道和下气道疾病的关系。过敏性哮喘。免疫。Res. 2017, 9, 126–132.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 雷法特,M.M.;埃尔赛义德;阿卜杜勒·法塔赫;艾尔班纳;Sayed,H.M.E.埃及患者痰膜骨质水平与炎症性哮喘表型之间的关系。J.哮喘。 2021, 58, 1285–1291.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 姚玲玲;宋J.;孟晓华;葛俊英;杜,B.X.;于杰;Ji, F.H. 骨膜蛋白在心肌缺血再灌注损伤中加重 NLRP3 炎症小体介导的焦亡。摩尔细胞探针。 2020, 53, 101596.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 新墨西哥州兰德里;科恩;Dixon,I.M.C. 骨脂蛋白在心血管疾病和发展中:两个不同角色的故事。基本分辨率 心脏。 2018, 113, 1.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 朱燕;纪建军;王晓德;孙晓杰;李敏;魏琦;任立强;Liu, N.F. Periostin通过PPARγ相关的葡萄糖代谢重编程促进动脉钙化。Am. J. 生理学. 心脏循环. 生理学. 2021, 320, H2222–H2239.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 岛崎;中村;纪伊,I.;鹿岛;北卡罗来纳州阿米冢;李敏;斋藤;福田;西山;北岛;等。骨皮素对于急性心肌梗死后的心脏愈合至关重要。医学实验 2008, 205, 295–303.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 崔永;哦,H.;安,M.;康;春,J.;申,T.;Kim,J.实验性自身免疫性心肌炎刘易斯大鼠心脏中骨皮蛋白的免疫组织化学分析。J. 兽医医学 2020, 82, 1545–1550.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 袁志棠;李晓新;程庆军;王玉华;王建华;MiR-30a通过靶向蜗牛1来调节心房颤动诱导的心肌纤维化。国际 J. 克林. 帕托尔. 2015, 8, 15527–15536.[谷歌学术][公共医学]

- 贾纳;奥伊拉;胡明;基利奇;扎比耶耶夫;麦卡洛克;奥迪特;Kassiri,Z. Gelsolin是血管紧张素II诱导的心脏成纤维细胞和纤维化活化的重要介质。法塞布· 2021, 35, e21932.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 郭辉辉;谢贤贤;王南昌;张志英;洪志贤;郭錤;刘玉瑞;李春英;Liu, P.L. 辛伐他汀通过调节心肌细胞衍生的外泌体分泌来减轻心脏纤维化。J·克林. 2019, 8, 794.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 白野;北卡罗来纳州木村;吉冈;穆凯;木村;冈田;洋津;舒库纳米,C.;平木;工藤;等。骨膜素通过诱导人类和啮齿动物的血管生成和MMP产生来推进动脉粥样硬化和风湿性心脏瓣膜变性。J·克林。投资。 2010, 120, 2292–2306.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 廖彦;李刚;张鑫;黄文;谢丹;戴刚;朱淑贤;卢德;张忠;林俊杰;等. 心脏巢蛋白(+)间充质基质细胞通过骨膜蛋白介导的M2巨噬细胞极化增强缺血性心脏的愈合。摩尔·瑟。 2020, 28, 855–873.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 胡燕;王旭;丁芳;刘春;王淑贤;冯彤;Meng, S. Periostin通过促细胞凋亡使心肌细胞易发生急性心肌梗死。ESC心力衰竭。 2022, 9, 977–987.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 索兹门;德夫里姆;卡巴克;Devrim,T. Periostin改变了异丙肾上腺素诱导的心脏毒性大鼠模型中的转录谱。哼哼。 2019, 38, 255–266.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 陈志;谢杰;郝华;林旭;王林;张燕;陈林;曹曹;黄霞;廖文;等。骨膜蛋白消融抑制由磷脂酰肌醇 3 激酶/糖原合酶激酶 3β/细胞周期蛋白 D1 信号通路介导的新生小鼠梗死后心肌再生。心脏血管研究 2017, 113, 620–632.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 吴华;李国;谢杰;李瑞;陈庆华;陈建忠;魏志华;康立;Xu, B. 白藜芦醇通过抑制 STZ 诱导的糖尿病小鼠的 ROS/ERK/TGF-β/骨膜蛋白途径来改善心肌纤维化。BMC 心脏血管。不和谐。 2016, 16, 5.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 王丹;奥帕里尔;冯,J.A.;李平;佩里;陈立邦;戴敏;约翰;压力超负荷对心房利钠肽-零小鼠心脏细胞外基质表达的影响。高血压 2003, 42, 88–95.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 马文强;孙晓杰;朱燕;Liu, N.F. 二甲双胍通过抗铁死亡作用减轻高脂血症相关的血管钙化。自由拉迪克。 生物医学 2021, 165, 229–242.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 内田;白石;太田;有马;谷口;铃木;冈本;阿尔菲尔德;大岛;加藤;等。骨膜蛋白是一种母细胞蛋白,在肺纤维化中诱导趋化因子中起作用。阿姆·细胞分子生物学. 2012, 46, 677–686.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 南里;努诺村;寺崎;吉原;平野;横崎;山口,Y.;费加利-博斯特威克;阿吉托;村上;等。转化生长因子-β和骨膜素之间的串扰可靶向肺纤维化。阿姆·细胞分子生物学. 2020, 62, 204–216.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 卡尔帕尼亚诺,GE;索西奥;西奥西亚;帕拉迪诺;福斯奇诺·巴巴罗,议员;莱塞多尼亚,D.气道骨膜蛋白在受特发性肺纤维化影响的患者的临床实践中的潜在作用。复兴研究 2021, 24, 302–306.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 施尼德;马马扎基波夫;伯恩胡贝尔;威廉;夸皮谢夫斯卡;鲁珀特;马尔卡特;乌贾克;卢比奥;巴雷托;等。LRP1的缺失促进收缩肌成细胞表型的获得和ECM储存中活性TGF-β1的释放。基质生物学。 2020, 88, 69–88.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 阿什利;加利福尼亚州威尔克;金国强;Moore,B.B.Periostin调节纤维细胞功能以促进肌成纤维细胞分化和肺纤维化。粘膜。免疫。 2017, 10, 341–351.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 兰伯特;门德斯-费雷拉;马里兰州吉尼亚;勒里博兹;阿当;博特;卡普阿诺;拉克-马丁;布拉斯-席尔瓦;夸克;等。Kcnk3功能障碍夸大了左心室压力超负荷引起的肺动脉高压的发展。心脏血管研究 2021, 117, 2474–2488.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 聂晓;沈春;谭,J.;吴志;王文;陈彦;戴英;杨晓;叶,S.;陈杰;骨膜素:肺动脉高压的潜在治疗靶点?Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1138–1152.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 关军;刘文强;邢;施彦;谭晓彦;蒋春强;Dai, H.Y. 糖尿病心肌病中骨膜素表达升高及缬沙坦的作用。BMC 心脏血管。不和谐。 2015, 15, 90.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 曾海林;陈丹;闫军;杨秦;韩庆强;李淑贞;Cheng, L. 危重 COVID-19 患者支气管肺泡灌洗液的蛋白质组学特征。2月J. 2021, 288, 5190–5200.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- Wan, J.; Shan, Y.; Song, X.; Chen, S.; Lu, X.; Jin, J.; Su, Q.; Liu, B.; Sun, W.; Li, B. Adipocyte-derived Periostin mediates glucocorticoid-induced hepatosteatosis in mice. Mol. Metab. 2020, 31, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Kanno, K.; Nguyen, P.T.; Sugiyama, A.; Kawahara, A.; Otani, Y.; Kishikawa, N.; Ito, M.; Tazuma, S. Periostin antisense oligonucleotide prevents hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in a mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 35, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wu, S.; Ouyang, G. Periostin: A new extracellular regulator of obesity-induced hepatosteatosis. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 朱建忠;朱海涛;戴英恩;李春兴;方志英;赵建军;万新英;王玉明;王芳;俞志华;等。血清骨膜蛋白是非酒精性脂肪性肝病的潜在生物标志物:一项病例对照研究。内分泌 2016, 51, 91–100.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 库马尔;史密斯;雷曼;乔皮克;布林克;刘燕;苏尔切克;Anania, F.A. Periostin通过激活肝星状细胞中的赖氨酰氧化酶来促进肝纤维化。J. 生物化学 2018, 293, 12781–12792.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 吴彤;黄军;吴淑贤;黄志;陈晓;刘燕;崔;宋,G.;罗玲玲;刘芳;等。骨皮蛋白缺乏会损害部分肝切除术后小鼠的肝脏再生。基质生物学。 2018, 66, 81–92.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 卞,X.;白轩轩;苏,X.;赵国;孙,G.;Li,D.骨膜蛋白的敲低可减轻5/6肾切除术诱导的大鼠肾内肾素 - 血管紧张素系统激活,纤维化和炎症。J.细胞生理学。 2019, 234, 22857–22873.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 普拉库拉,北卡罗来纳州;卡夫瓦达斯;科尔曼;杜索尔;查吉克里斯托斯;Chatziantoniou,C. NFκB诱导的骨膜蛋白激活整合素-β3信号传导以促进GN的肾损伤。J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1475–1490.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 张燕;赖夫;华莱士,D.P.多囊肾病中的细胞外基质,整合素和局灶粘附信号传导。细胞信号。 2020, 72, 109646.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 盖罗特;杜索尔;梅尔-艾宁;徐杜波依斯;朗多;查齐安托尼乌;Placier,S.确定骨膜蛋白作为高血压肾病进展/逆转的关键标志物。公共科学图书馆一号2012,7,e31974。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 萨蒂拉波伊;王轩;张伯林;戴淑娴;拉佩奇;菲利普斯;纳斯特;Adler,S.G.骨膜蛋白:进行性肾损伤的新型组织和尿液生物标志物诱导肾小管细胞中协调的间充质表型。肾瘟。拨号。移植。 2012, 27, 2702–2711.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 梅尔-艾宁;阿贝德;康威;杜索尔;Chatziantoniou,C.抑制骨膜蛋白表达可防止肾脏炎症和纤维化的发展。J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1724–1736.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 安,J.N.;杨淑贤;金永昌;黄建华;帕克;金,D.K.;金斌;金德华;胡尔;哦,是的;等。骨皮蛋白通过p38 MAPK途径诱导急性肾损伤后的肾纤维化。生理学博士。 2019, 316, F426–F437.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 阿莱苏坦,I.;洛杉矶亨泽;博姆;梁,T.T.D.;齐克勒;皮斯克;肯萨诸塞州埃卡特;帕施;Voelkl,J.Periostin通过β-连环蛋白信号传导增强血管平滑肌细胞钙化。生物分子 2022, 12, 1157.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 科尔曼;卡夫瓦达斯;普拉西耶;范德米尔施;多里森;杜索尔;查吉克里斯托斯;普拉库拉,北卡罗来纳州;Chatziantoniou,C. periostin促进细胞增殖和巨噬细胞极化,以驱动AKI后的修复。J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 85–100.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 吴军;林炳;李淑贞;邵晓;朱鑫;张明;周文;Ni,Z.Periostin通过促进系膜细胞的增殖来促进免疫球蛋白A肾病:加权基因相关网络分析。前面。热内。 2020, 11, 595757.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 埃尔道拉,新墨西哥州;萨拉姆,上午;埃尔-赫夫纳维,马里兰州;El-Mesallamy,H.O.E-钙粘蛋白和骨膜蛋白在糖尿病肾病的早期检测和进展中的应用:上皮到间充质的过渡。克林· 2019, 23, 1050–1057.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 许,S.J.;崔永;金玟哉;李,K.L.;金德华;金斌;金J.W.;Kim,J.S.母细胞蛋白骨膜蛋白通过激活核因子κB信号传导介导肠道炎症。公共科学图书馆一号2016,11,e0149652。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 科埃略;索嫩贝格-里斯马赫;高彦;莫索托;霍亚纳扎罗夫;格里芬;穆卡诺娃;阿希姆哈诺娃;哈加蒂;鲍里森科;等。母细胞蛋白骨质蛋白骨质蛋白在小儿炎症性肠病中的表达谱。科学代表 2021, 11, 6194.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 凯斯金;托普卡奇,A.骨皮苷诊断克罗恩病的预测价值。土耳其人J.胃肠醇。 2022, 33, 127–135.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 北卡罗来纳州邦尼特;肯塔基州斯坦德利;比安奇;斯塔德尔曼;福蒂;康威;法拉利母质蛋白骨脂蛋白是抑制sost和对机械负荷和体力活动的合成代谢反应所必需的。J. 生物化学 2009, 284, 35939–35950.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 李春;李晓;王旭;苗,P.;刘军;李春;李丹;周文;金志;Cao, M. Periostin介导卵巢切除大鼠雌激素诱导的骨髓基质细胞成骨分化。生物医学研究国际 2020, 2020, 9405909.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 刘淑贞;金志;曹明;郝,D.;李春;李丹;Zhou, W. Periostin通过对ILK / Akt / GSK-3β轴的作用调节卵巢切除大鼠间充质干细胞的成骨。基因. 分子生物学. 2021, 44, e20200461.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 克尔尚-辛德尔;埃本比希勒;美国福格-萨姆瓦尔德;莱斯;盖斯鲍尔;赫尔采格;斯塔姆沃尔;马库列斯库;克雷文纳;Pietschmann,P.类风湿性关节炎缓解 :肌生长抑制素降低,血清骨膜素水平升高。维也纳。克林。沃亨施尔。 2019, 131, 1–7.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 千岛松;库努吉扎;谷山;北卡罗来纳州中村;富田;Yoshikawa,H.骨膜蛋白在人骨关节炎软骨中的表达和病理作用。BMC肌肉骨骼。不和谐。 2015, 16, 215.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 韩·米尼亚蒂;艾布拉姆森;Attur,M.Periostin与盘状结构域受体-1(DDR1)的相互作用促进软骨变性。公共科学图书馆一号2020,15,e0231501。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 中村;斋藤;小村;松本;小川;宫川;斋藤;今村;今井;高柳;等。由于髋关节脱位引起的动态负荷降低,通过 STAT3/骨膜素/NF-κB 轴诱导 IL-6 和 MMP3 导致髋臼软骨变性。科学代表 2022, 12, 12207.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 朱丹;王志;张刚;马春;邱晓;王轩;刘敏;郭晓明;陈华;邓琦;等。骨膜蛋白通过激活Wnt/β-连环蛋白信号通路促进髓细胞核凋亡。法塞布· 2022, 36, e22369.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 塔吉卡;穆埃;石川;浅野;奥库莫;高木;Hisamitsu,T.骨膜素对膝关节骨关节炎滑膜细胞的影响。体内 2017, 31, 69–77.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 佩佩;北卡罗来纳州邦尼特;奇普里亚尼;费拉拉;罗西;德马蒂诺;科朗基洛;索纳托;切切蒂;法拉利;等。组织蛋白酶 K 生成的骨膜蛋白片段血清水平较高与原发性甲状旁腺功能亢进症绝经后妇女的骨折有关:一项试点研究。骨质疏松症。 国际 2021, 32, 2365–2369.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 岛村;谷山;北卡苏拉吉;北卡罗来纳州小井渊;久德;佐藤;阿拉塔瓦科利;和歌山;中上;Morishita,R.中枢神经系统骨膜素在脑缺血中的作用。中风 2012, 43, 1108–1114.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 高山;有马;卡纳吉;户田;田中;庄司;麦肯齐;永井;穗池渊,T.;Izuhara,K. Periostin:IL-4和IL-13信号下游支气管哮喘上皮下纤维化的新成分。J.过敏克林。免疫。 2006, 118, 98–104.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 约翰逊;安尼斯;Mosher,D.F.α(M)β(2)整合素介导的IL-5刺激的嗜酸性粒细胞对骨膜蛋白的粘附和运动。阿姆·细胞分子生物学. 2013, 48, 503–510.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 谷山;北卡苏拉吉;真田;阿祖玛;家库西;北卡罗来纳州小井渊;冈山;池田岩部;村津,J.;大津;选择性阻断骨膜蛋白外显子17保留急性心肌梗死的心脏性能。高血压 2016, 67, 356–361.[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 南斯;史密斯;安纳亚;理查森;何立;帕拉,马里兰州;穆斯塔法维;巴特尔,A.;费加利-博斯特威克;罗森;等。转录组分析揭示了IPF肺组织中的差异剪接事件。公共科学图书馆一号2014,9,e92111。[谷歌学术][交叉参考]

- 中间;吉田;石川;小林;安倍,T.;清成;盐井;北卡苏拉吉;石桥;森下;等。骨膜蛋白剪接变异在视网膜新生血管形成中起的不同作用。实验眼部研究 2016, 153, 133–140.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- 蔡,L.;布罗菲;泰克森;段旭;努利;Rai,M.F.软骨细胞和韧带祖细胞中骨筋膜剪接变异的独特表达模式。法塞布· 2019, 33, 8386–8405.[谷歌学术][交叉参考][公共医学]

- Ono, J.; Takai, M.; Kamei, A.; Nunomura, S.; Nanri, Y.; Yoshihara, T.; Ohta, S.; Yasuda, K.; Conway, S.J.; Yokosaki, Y.; et al. Periostin forms a functional complex with IgA in human serum. Allergol. Int. 2020, 69, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, R.A.; Damon, B.; Mironov, V.; Kasyanov, V.; Ramamurthi, A.; Moreno-Rodriguez, R.; Trusk, T.; Potts, J.D.; Goodwin, R.L.; Davis, J.; et al. Periostin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis and the biomechanical properties of connective tissues. J. Cell Biochem. 2007, 101, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Arai, C.; Ishikawa, M.; Shimoda, S.; Nakamura, Y. Fiber system degradation, and periostin and connective tissue growth factor level reduction, in the periodontal ligament of teeth in the absence of masticatory load. J. Periodontal. Res. 2011, 46, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruhashi, T.; Kii, I.; Saito, M.; Kudo, A. Interaction between periostin and BMP-1 promotes proteolytic activation of lysyl oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 13294–13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, D.; Kubo, T.; Kiya, K.; Kawai, K.; Matsuzaki, S.; Kobayashi, D.; Fujiwara, T.; Katayama, T.; Hosokawa, K. Periostin is induced by IL-4/IL-13 in dermal fibroblasts and promotes RhoA/ROCK pathway-mediated TGF-β1 secretion in abnormal scar formation. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 2019, 53, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Fan, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.Y.; Cui, X.B.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, L.L. Angiotensin II increases periostin expression via Ras/p38 MAPK/CREB and ERK1/2/TGF-β1 pathways in cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanisicak, O.; Khalil, H.; Ivey, M.J.; Karch, J.; Maliken, B.D.; Correll, R.N.; Brody, M.J.; SC, J.L.; Aronow, B.J.; Tallquist, M.D.; et al. Genetic lineage tracing defines myofibroblast origin and function in the injured heart. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, K.; Chen, S.; Chai, J.; Yan, W.; Zhu, X.; Dai, H.; Wang, W. Upregulation of Periostin Through CREB Participates in Myocardial Infarction-induced Myocardial Fibrosis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 79, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Iyer, R.P.; Jung, M.; Czubryt, M.P.; Lindsey, M.L. Cardiac Fibroblast Activation Post-Myocardial Infarction: Current Knowledge Gaps. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider, P.; Hinton, R.B.; Moreno-Rodriguez, R.A.; Wang, J.; Rogers, R.; Lindsley, A.; Li, F.; Ingram, D.A.; Menick, D.; Field, L.; et al. Periostin is required for maturation and extracellular matrix stabilization of noncardiomyocyte lineages of the heart. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drasutiene, A.; Chitwood, W.R.; Rucinskas, K.; Aidietis, A. Reoperative, transapical off-pump neochordae implantation for recurrent degenerative mitral regurgitation resulting from a newly ruptured native chord. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2020, 58, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xie, J.; Li, G.N.; Chen, Q.H.; Li, R.; Zhang, X.L.; Kang, L.N.; Xu, B. Possible involvement of TGF-β/periostin in fibrosis of right atrial appendages in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 6859–6869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Horne, T.E.; VandeKopple, M.; Sauls, K.; Koenig, S.N.; Anstine, L.J.; Garg, V.; Norris, R.A.; Lincoln, J. Dynamic Heterogeneity of the Heart Valve Interstitial Cell Population in Mitral Valve Health and Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2015, 2, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkatchenko, T.V.; Moreno-Rodriguez, R.A.; Conway, S.J.; Molkentin, J.D.; Markwald, R.R.; Tkatchenko, A.V. Lack of periostin leads to suppression of Notch1 signaling and calcific aortic valve disease. Physiol. Genomics. 2009, 39, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Chen, L.; Xie, J.; Li, R.; Li, G.N.; Chen, Q.H.; Zhang, X.L.; Kang, L.N.; Xu, B. Periostin expression induced by oxidative stress contributes to myocardial fibrosis in a rat model of high salt-induced hypertension. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, V.; Wang, Q.; Conley, B.A.; Friesel, R.E.; Vary, C.P. Vascular injury induces expression of periostin: Implications for vascular cell differentiation and migration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Nakama, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Nakao, S.; Sonoda, K.H.; Ishibashi, T. Periostin in vitreoretinal diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 4329–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Shujuan, G.; Ping, H.; Li, L.; Weiwei, S.; Yafei, W.; Weidong, T. Wnt5a up-regulates Periostin through CaMKII pathway to influence periodontal tissue destruction in early periodontitis. J. Mol. Histol. 2021, 52, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Honda, T.; Miyauchi, S.; Yamazaki, K. Th2 cytokines efficiently stimulate periostin production in gingival fibroblasts but periostin does not induce an inflammatory response in gingival epithelial cells. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2014, 59, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, M.P.; Soler, Z.M.; Kao, S.Y.; Metson, R.; Stankovic, K.M. Topographic gene expression in the sinonasal cavity of patients with chronic sinusitis with polyps. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłoński, J.; Zielińska-Bliźniewska, H.; Przybyłowska, K.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Korzycka-Zaborowska, B.; Majsterek, I.; Olszewski, J. Significance of CYCLOOXYGENASE-2(COX-2), PERIOSTIN (POSTN) and INTERLEUKIN-4(IL-4) gene expression in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2015, 272, 3715–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Fan, E.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Bachert, C. Association of periostin expression with eosinophilic inflammation in nasal polyps. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 1700–1703.e1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, S.; Lu, X.; Purkey, M.R.; Homma, T.; Choi, A.W.; Carter, R.; Suh, L.; Norton, J.; Harris, K.E.; Conley, D.B.; et al. Increased expression of the epithelial anion transporter pendrin/SLC26A4 in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 1548–1558.e1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxfield, A.Z.; Landegger, L.D.; Brook, C.D.; Lehmann, A.E.; Campbell, A.P.; Bergmark, R.W.; Stankovic, K.M.; Metson, R. Periostin as a Biomarker for Nasal Polyps in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Xu, M. Effect of posterior nasal neurectomy on the suppression of allergic rhinitis. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigo-Muñoz, J.M.; Cañas, J.A.; Sastre, B.; Gil-Martínez, M.; García Latorre, R.; Sastre, J.; Del Pozo, V. Role of miR-185-5p as modulator of periostin synthesis and smooth muscle contraction in asthma. J. Cell Physiol. 2022, 237, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Liang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, H.; He, J.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Decreased epithelial and sputum miR-221-3p associates with airway eosinophilic inflammation and CXCL17 expression in asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315, L253–L264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejman-Gryz, P.; Górska, K.; Paplińska-Goryca, M.; Proboszcz, M.; Krenke, R. Periostin and Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin-Potential Crosstalk in Obstructive Airway Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]