Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

A psychopathological phenomenon is an experienced condition whose peculiar features emerge within an interpersonal context. In different interpersonal (e.g., socio-cultural) contexts and in different contexts of care (e.g., bio-medical, psychotherapeutic or community settings), different phenomena may emerge from the same patient and they can be given different psychopathological significance. Symptom variance (which is taboo for ticking-boxes interviewing techniques) is an effect of the milieu in which a given phenomenon emerges.

- causality

- culture

- diagnosis

- images

1. Linking Dots: An Alternative Emergent Way to Discovery

Should we not give up some of the claims to reliability, linear causality and objectivity and admit that discovery in psychopathology necessary produces emergent knowledge?

In the following, I develop an argument to support an alternative way to knowledge and discovery based on the emergent properties of psychopathological phenomena. I call this approach linking dots. The “dots” at issue here are basically fragments of lived experience provided by the patients themselves as pieces of their personal history, experienced situations, emotions, beliefs, imagination, dreams and so on, or arise in the intersubjective space between the patient and the clinician during the clinical encounter. I will refer to these fragments of lived experience or “singular phenomena” with the term “images”. The reason for choosing this word is that these “images” should be thought of as pictures to be hung on a wall, ideally posited in front of the patient and the clinician, and patiently collected before the “links” between them arise spontaneously or semi-spontaneously in the patient’s and the clinician’s minds.

I will build on and develop the approach to images and discovery devised by art historian Aby Warburg in his atlas of images Bilderatlas Mnemosyne [1]. Aby Moritz Warburg described himself as “Hamburger at heart, Jew by blood, Florentine in spirit”. Born of a wealthy German Jewish family of Italian origins in Hamburg in 1866, he studied art history, history of religion and archaeology in Bonn. He also trained for two semesters in medicine in Berlin. At the end of the 19th century, he moved to Florence, where he developed an entirely original understanding of Antiquity and the Renaissance, which remained his main interest throughout his life. In the years after his mental breakdown at the end of the First World War, which shook Europe’s civilizing project at the core and sent him to Ludwig Binswanger’s psychiatric clinic Bellevue from 1919 till 1924 [2], the Bilderatlas became his major focus. Created in the late 1920s, its final version (October 1929) consisted of 63 wooden panels covered with black cloth, on which were pinned about 1000 pictures from books, magazines, newspapers and other daily life sources.

This collection of images is reminiscent of a very similar project started in the same period by German Jewish philosopher and cultural and literary critic Walter Benjamin (1982–1940) [3] called Passagen-Werk (translated Arcades Project) [4], an enormous collection of quotes from heterogenous “sources” (as those used by Warburg) illustrating the city life of Paris in the mid-19th century. Benjamin’s project was inspired by an emblematic figure of the new metropolitan life: the ragpicker. The ragpicker, writes Benjamin, catalogues and collects everything the big city has rejected, everything it has lost, everything it has disdained, everything it has torn to pieces [4]. The analogy between the psychiatrist and the ragman leaps to the eye; both are interested in collecting and recycling the rags and scraps of human existence. It is in his attempt to reconstruct the profound transformation taking place in the Western world in the mid-19th century that Benjamin decides to adopt the principle of montage as an epistemological principle on which to base a new, anti-historical approach to the understanding and the critique of culture. The quotations collected by Benjamin in this unfinished work are neither arranged in chapters or sections, nor commented on, but simply juxtaposed with one another. It is left to the reader to link the dots.

Similar to Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne, in the field of art critique, the Arcades Project is a methodological touchstone for the process of knowledge generation. The visual constellations created by Warburg in the series of panels of the Bilderatlas can be understood as a cultural method that uses spaces and surfaces to reveal the layers of memory and the web of relationships manifested in them. Panels invite the viewer to participate in the production of meanings, forging ever new connections between the images. It is the viewer’s acts of perception that draw relationships between singularities. This method is deemed of enormous significance in the context of today’s social and cultural crisis and transformation processes, which can no longer be comprehended using the categories of existing knowledge systems [5].

2. Images and Discovery

Let us briefly present the basic steps in Warburg’s method and begin to establish a parallel with linking dots in clinical practice.

The first step consists of the establishment of an archive or collection of images gathered during the process of discovery (in the clinical context, the psychopathological interview) [6]. Warburg defines the units of the collection as Pathosformeln. Pathosformeln are images in which a given pathos—i.e., an emotional energy, an affective state—coagulates in a formula—i.e., a culturally transformed model [7]. Thus, Pathoformeln are deposits and transformers of affective/emotional drives. They give expression to the movement of life, making visible a certain emotional movement; they unite an invisible, internal state with a bodily, visible form. Pathosformeln create a space, a distance between the person and her internal state through a kind of objectification that shapes and begins a space for thought.

A network of resonating images thus emerges. It may be called Figura. A Figura is a web of images reverberating with each other that is established thanks to linking dots between the individual images. Within a Figura, each image constitutes a nucleus for the discernment of other images that relate to it. As noted in the section on emergentism, two factors are involved in this networking process. First, the images of the archive resonate with each other. Second, the images resonate with observers’ gazes. These resonances may originate without an active, voluntary and rational contribution by the observer, or via the application of some sort of pre-established algorithm. They depend on the way the beholder engages with what he sees. Thus, what is revealed are not atemporal essences, but rather the outcome of the here-and-now subject–object engagement. An illuminating analogy is provided by Walter Benjamin [8]; these Figurae are to each image that composes them as constellations are to stars. Their prototypes are star constellations; just as the constellations we see in the starry night are not how stars aggregate according to the laws of nature, but according to the human eye that sees them from afar and groups them into perspicuous configurations, so too these networks are “constructed” in the eye of the beholder.

Building on such a semi-spontaneously formed network of images, the next step consists of an active montage of resonant images. The images are not mounted on the basis of inductive or deductive operations, but by their exemplary or paradigmatic characteristics. The juxtapositions are not even based on a diachronic temporal logic; the elements of this archive are collected without regard to the linear model of temporality. The connection between such images is analogical, i.e., based on similarity or ‘family resemblance’ [9]. Analogy is suspended between an emotional logic and a formal logic, and is in tension between these.

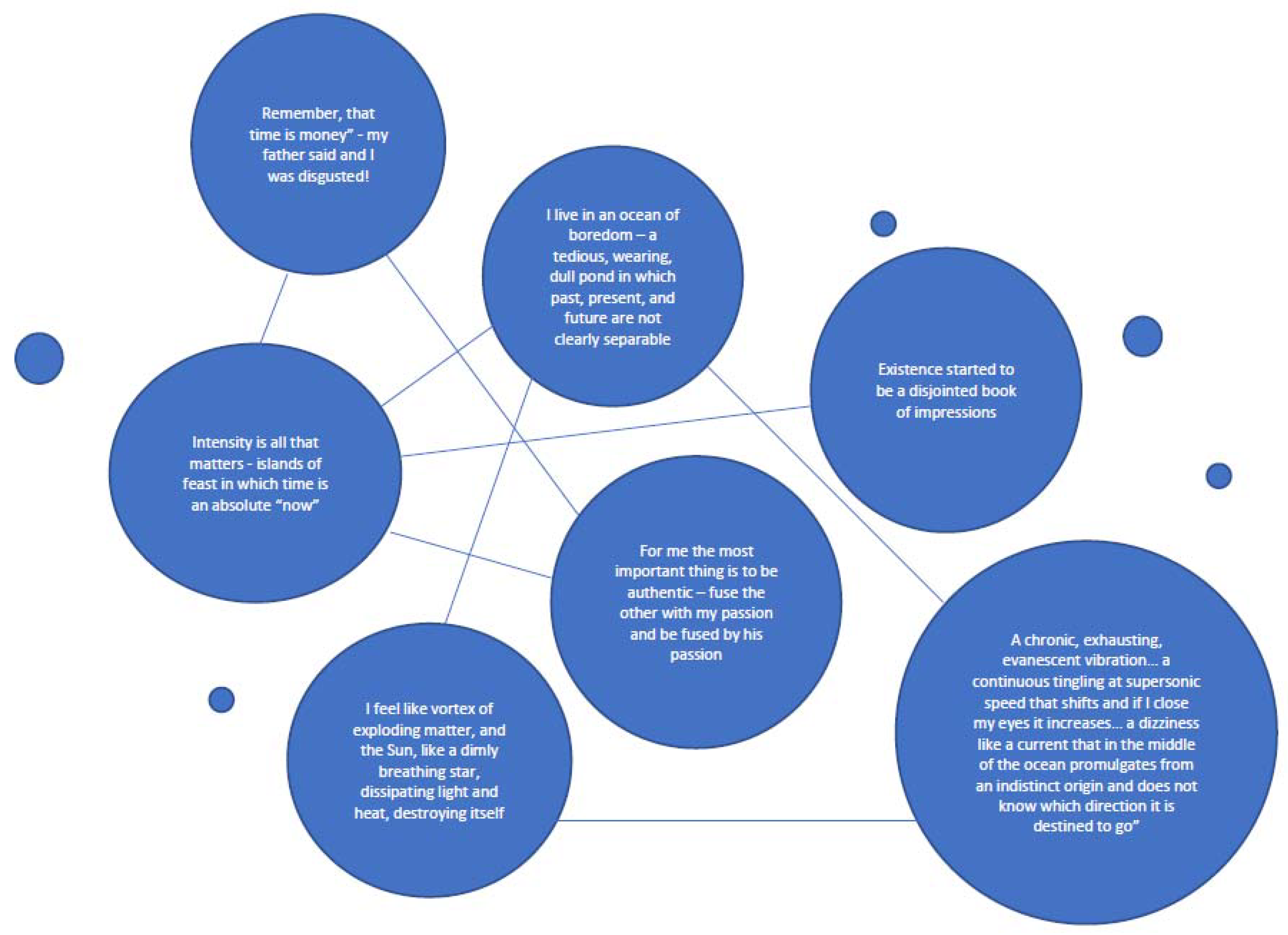

The constellation of images highlights hidden aspects of each image that only reveal themselves in the presence of this juxtaposition. The figurative links, semi-spontaneously emerged (resonance) and actively established (montage), uncover what, in Benjamin’s words, It may be called “optical unconscious” [10]. Within this network, a Figura contributes to make each image more perspicuous and more meaningful. Furthermore, when individual images form a Figura, they also give rise to figurative causes. Figurative links within a Figura generate figurative causes since they transform each single image, metamorphosing it. The figurative nexus that emerges in the present retroacts on the image that comes from the past (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Linking dots. Images from a dissipating style of existence.

These are the steps of this process, but the process itself is never completed. This network of images forms an open construction, not a closed one such as a diagnostic category or the teleology of certain narratives. They provide a space for thought [11]. This network constitutes the space for discovery, for the birth of a new thought.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/brainsci13010013

References

- Warburg, A. Bilderatlas Mnemosyne: The Original; Haus der Kulturen und Welt (HKW): Berlin, Germany; Yje Warburg Institute: London, UK, 2020.

- Binswanger, L.; Warburg, A. La Guarigione Infinita. Storia Clinica di Aby Warburg; Santilli, D., Ed.; Neri Pozza: Vicenza, Italy, 2005.

- Calderòn, U.; Felipe, J. El Montaje en Aby Warburg y en Walter Benjamin. Un Método Alternativo para la Representaciòn de la Violencia; Editorial Universitad del Rosario: Bogotà, Colombia, 2017.

- Benjamin, W. The Arcades Project; Belnknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999.

- Sherma, B. Under the sign of Mnemosyne. In Aby Warburg Bilderatlas Mnemosyne—The Original; Ohrt, R., Heil, A., Eds.; The Warburg Institute: London, UK, 2020; pp. 8–9.

- Stanghellini, G.; Mancini, M. The Therapeutic Interview; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018.

- Agamben, G. Ninfe; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2007.

- Benjamin, W. The Task of the Translator. Selected Writings; Bullock, M., Jennings, M.W., Eds.; The Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1996; Volume I, pp. 253–263.

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations; Blackwell Publishing: London, UK, 2001.

- Benjamin, W. Short History of Photography. In On Photography; Leslie, E., Ed.; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 2001; pp. 59–108.

- Warburg, A. Symbolismus als Umfangsbestimmung. In Werke in Einem Band; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 615–628.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!