Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Spodoptera frugiperda is a major pest of maize crops. Essential oils (EOs) are a possible source of novel pesticides, due to the fact that they have contact, fumigant, attractant and repellent activities against several insect pests.

- natural insecticides

- insect pest

- phytochemicals

1. Introduction

The demand for food commodities has increased exponentially with population growth. It is estimated that the world population will be between 9.4 and 10.1 billion people in 2050 [1], implying a 35% increase in the demand for food [2]. Maize (Zea mays L.) is among the most cultivated cereals in the world, with a global production of 1185.90 million metric tons being expected in 2022–2023 [3]. However, crop losses occur due to the action of pests, such as insects and fungi [4]. To maximize crop yields, pest control currently involves the application of approximately 2 million tons of synthetic pesticides per year, of which 29.5% corresponds to insecticides [5].

The fall armyworm (FAW) Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) is among the most common pests of maize plants in the tropical regions of the Americas [6]. In addition, as a result of the expansion of agricultural frontiers, it is now considered to be an invasive pest in African countries, China, India and Australia [7][8][9][10][11][12]. Spodoptera frugiperda is a holometabolous insect [6][13]. From its eggs, the first of six larval stages emerges. These larvae are initially light green, after which they become dark green with three longitudinal yellowish and dark brown lines. Then, 15–25 days after emergence from the egg, the sixth stage larvae pupate, preferably in the soil for between 7 and 13 days, until completing the cycle again with the emergence of new adults [6][13].

The use of Bt maize varieties designed to resist chewing phytophagous insects, such as FAW, has been carried out since 1996 [14]. However, due to the continuous use of these maize varieties, numerous instances of resistance of S. frugiperda to the Cry1 protein of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) have been reported [15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]. Therefore, the search for new pest control strategies has to be continued. Related to this, the search for sustainable alternatives is becoming more ever popular [15], with the exploitation of natural products obtained from the secondary metabolism of plants being an ecofriendly attractive alternative [20][21][22].

Essential oils (EOs) are a possible source of novel pesticides, due to the fact that they have contact, fumigant, attractant and repellent activities against several insect pests [24][25][26][27][28].

2. Essential Oils Evaluated against Spodoptera frugiperda

An analysis was carried out which indicated the 11 most used plant families for obtaining EOs for toxicological studies on FAW (Table 1). More than 50% of the 27 selected articles referred to EOs obtained from just three plant families: Piperaceae, Lamiaceae and Verbenaceae, in order of decreasing frequency.

Table 1. Occurrence of families whose essential oil has been studied as an insecticide against Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Plant Family | Occurrence |

|---|---|

| Piperaceae | 13 |

| Lamiaceae | 12 |

| Verbenaceae | 10 |

| Myrtaceae | 5 |

| Asteraceae | 5 |

| Rutaceae | 3 |

| Poaceae | 3 |

| Zingiberaceae | 2 |

| Apiaceae | 1 |

| Siparunaceae | 1 |

| Geraniaceae | 1 |

| Total | 56 |

In total, 21 plant genera were identified in the bibliographical analysis (Table 2). The most frequently studied genus was Piper (13), from the Piperaceae family, followed by the genera Ocimum (9) and Lippia (9), both from the Lamiaceae family. In all, the evaluation identified a total of 57 plant species (Table 3). Of these, Ocimum basilicum, commonly known as “basil”, was the most used species, followed by Piper marginatum, the “marigold pepper, Ti Bombé or Hinojo”, and the “purple sage” Lippia alba.

Table 2. Plant genera whose essential oils have been evaluated as insecticides against Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Genera | Occurrence in Literature |

|---|---|

| Piper | 13 |

| Ocimum | 9 |

| Lippia | 9 |

| Eucalyptus | 5 |

| Hyptis | 3 |

| Cymbopogon | 3 |

| Foeniculum | 2 |

| Corymbia | 2 |

| Citrus | 2 |

| Siparuna | 1 |

| Ruta | 1 |

| Pelargonium | 1 |

| Mentha | 1 |

| Malva | 1 |

| Hyptis | 1 |

| Eremanthus | 1 |

| Tanacetum | 1 |

| Artemisia | 1 |

| Ageratum | 1 |

| Zingiber | 1 |

| Vanillosmopsis | 1 |

| Total | 60 |

Table 3. Plant species whose essential oils are evaluated as insecticides against Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Plant Species | Occurrences in the Literature |

|---|---|

| Ocimum basilicum | 4 |

| Lippia alba | 3 |

| Piper marginatum | 3 |

| Corymbia citriodora | 2 |

| Cymbopogon citratus | 2 |

| Eucalyptus staigeriana | 2 |

| Foeniculum vulgare | 2 |

| Hyptis marrubioides | 2 |

| Lippia microphylla | 2 |

| Lippia sidoides | 2 |

| Ocimum gratissimum | 2 |

| Piper arboreum | 2 |

| Piper corcovadensis | 2 |

| Piper hispidinervum | 2 |

| Ageratum conyzoides | 1 |

| Artemisia absinthium | 1 |

| Citrus aurantium | 1 |

| Citrus limon | 1 |

| Citrus sinensis | 1 |

| Cymbopogon winterianus | 1 |

| Eremanthus erythropappus | 1 |

| Eucalyptus citriodora | 1 |

| Eucalyptus urograndis | 1 |

| Eucalyptus urophylla | 1 |

| Hyptis suaveolens | 1 |

| Lippia gracilis | 1 |

| Lippia origanoides | 1 |

| Malva sp. | 1 |

| Mentha sp. | 1 |

| Ocimum selloi | 1 |

| Pelargonium graveolens | 1 |

| Piper aduncum | 1 |

| Piper septuplinervium | 1 |

| Piper subtomentosum | 1 |

| Ruta graveolens | 1 |

| Siparuna guianensis | 1 |

| Tanacetum vulgare | 1 |

| Vanillosmopsis arborea | 1 |

| Zingiber officinale | 1 |

| Total | 57 |

Most of the EOs used were extracted from the aerial parts of the plants, mainly the leaves, which were used dry or fresh. In general, the EOs were obtained from the aerial plant parts by the steam dragging distillation technique. However, EOs were obtained by cold pressing when extracted from the shell of the fruits belonging to the Citrus species. It is interesting to note that 35% of the articles analyzed (27) did not specify the plant organ used for the EO extraction.

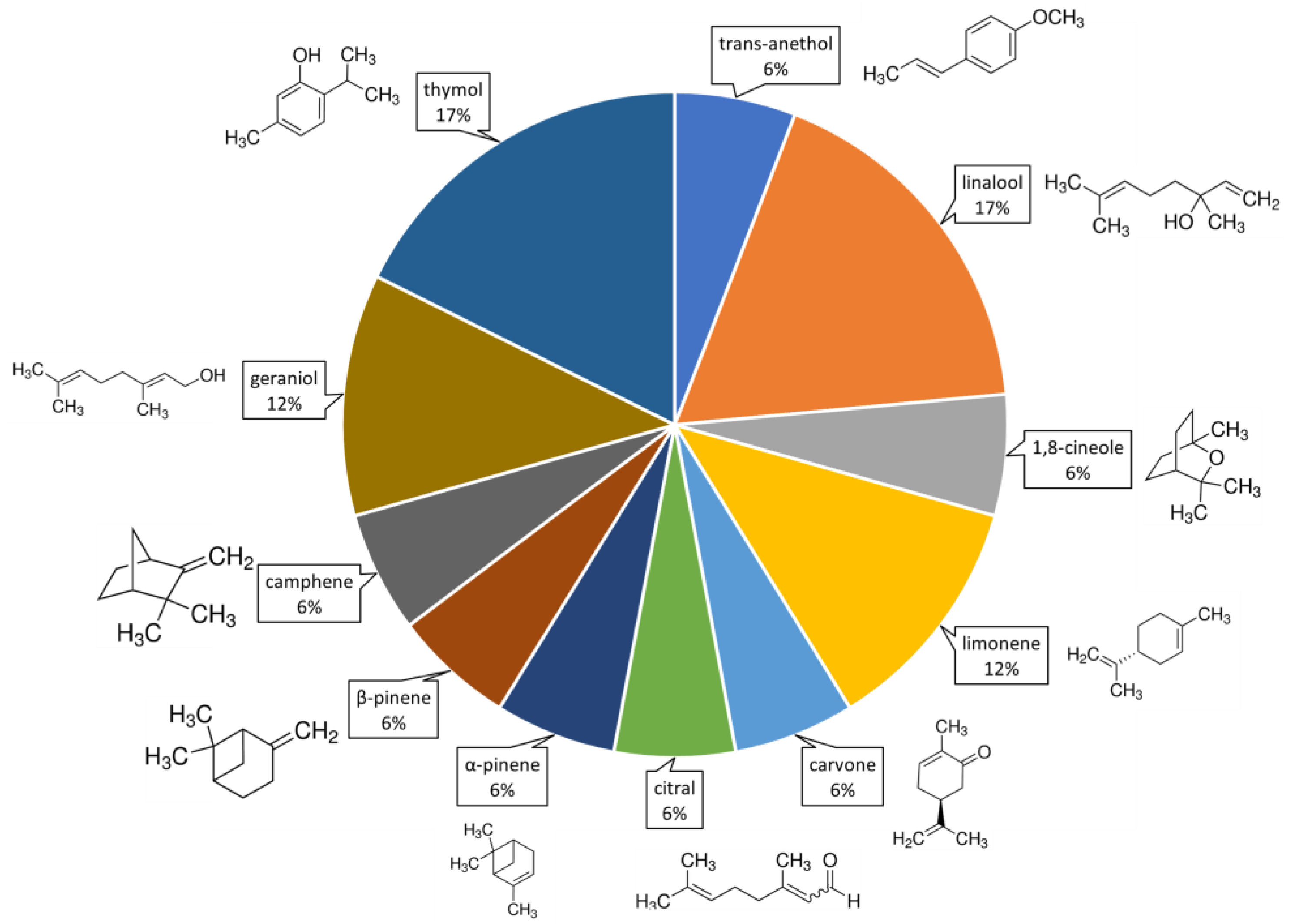

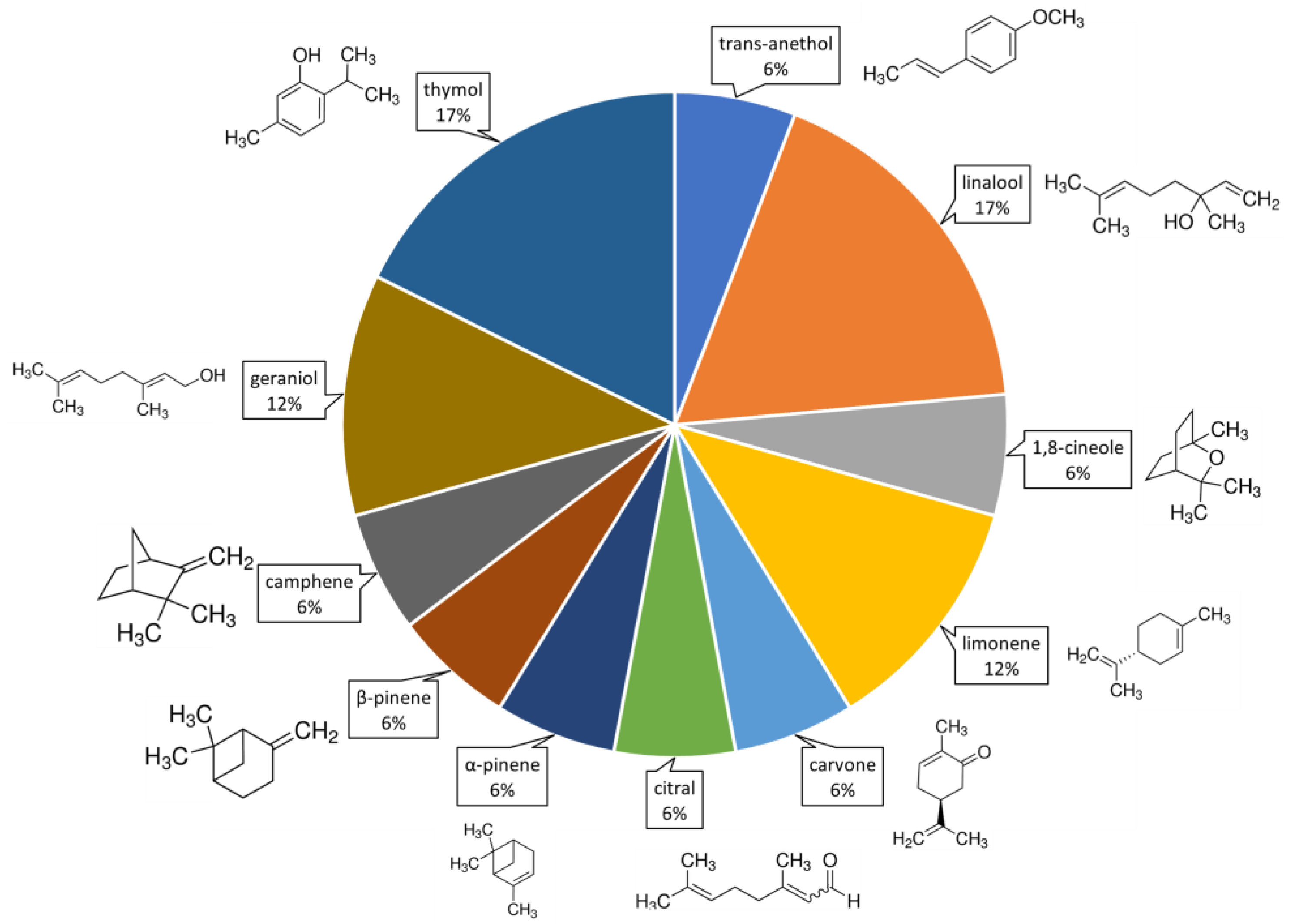

From the compositional analysis of the 57 EOs tested, 56 different main organic compounds were identified. The molecular structures of compounds mentioned in more than 5% of the literature are shown in Figure 1, with geranial, geraniol, linalool, α-pinene and limonene being the most frequent. The volatile organic compounds (VOCs) cited as being the major components of the 57 EOs used as insecticides against FAW. However, only 31% of the 27 articles analyzed complemented their toxicity studies with the use of pure EO compounds. Thymol and linalool were the most evaluated EO compounds (used in 17% of the studies), followed by limonene and geraniol (12%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Volatile volatile organic compounds (VOCs) used to evaluate toxicity against Spodoptera frugiperda. The percentages indicate the proportion of appearance of these compounds in the literature. Percentages were calculated based on 23% of articles (of 27 selected) that test pure VOCs.

Commercial insecticides can be a very useful tool for comparing the insecticidal effect of EOs. Nevertheless, only 41.6% of the articles used a commercial synthetic insecticide as the positive control, with 4% using the commercial natural insecticide neem extract (Azadirachta indica). Deltamethrin (12.5%), a synthetic pyrethroid pesticide used in livestock, aquaculture and agriculture due to its low residue and high toxicity, as well as because of its great efficacy, was the most frequently used synthetic insecticide as the positive control [29] (Table 4). Concerning the negative control, the one most used was acetone.

Table 4. Commercial insecticides used as positive controls against Spodoptera frugiperda.

| Positive Control Used in Bibliography | Occurrences in the Literature |

|---|---|

| neem extract (Azadirachta indica) | 2 |

| deltamethrin | 3 |

| α-cypermethrin | 1 |

| β-cypermethrin | 1 |

| fenpropathrin | 1 |

| δ-cyhalothrin | 1 |

| Indoxacarb | 1 |

| chlorpyrifos | 1 |

In the remaining 54.2% of the articles, positive controls were not used.

3. Routes of Entry of Essential Oils

The physicochemical properties of the EO molecules modulate the routes of entry into the organism [30][31]. EOs are lipophilic complex mixtures of hydrocarbon compounds of 10 to 15 carbon atoms with different functional groups, such as phenols, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols and hydrocarbons [24]. Lipophilicity is among the most important parameters to take into account when selecting bioactive compounds and the methods to test them, because the insect cuticle forms a physical defense barrier [32][33][34]. Thus, the lipophilicity property of EOs makes it easier for them to reach their target within the body [34][35][36][37]. It is widely known that organophosphate insecticides, such as Dichlorvos (DDVP), penetrate through the integument until they reach the hemolymph and, subsequently, their site of action [38][39]. In turn, there is a correlation between resistance to insecticides and cuticular penetration [40][41][42]. The non-polar nature of the insect cuticle, composed mainly of aliphatic hydrocarbons, chitin and waxes, could favor the entry of lipophilic compounds, such as those present in EOs [33][40][43][44]. Thus, this is a critical property to be considered when choosing a method to assess the toxicity of EOs on S. frugiperda.

Another important factor to consider in EOs is their high volatility. Therefore, the way of applying the EOs and their persistence over time must be considered when evaluating their toxicity, not only in terms of the method of application, but also of the development temperature of the test [45]. Related to this, Papachristos and Stamopoulos [46] were the first to determine the importance of the temperature at which the test is carried out on the rate of vapor release and the absorption levels of EOs, and also on the effectiveness of the enzymatic machinery for detoxification of insects.

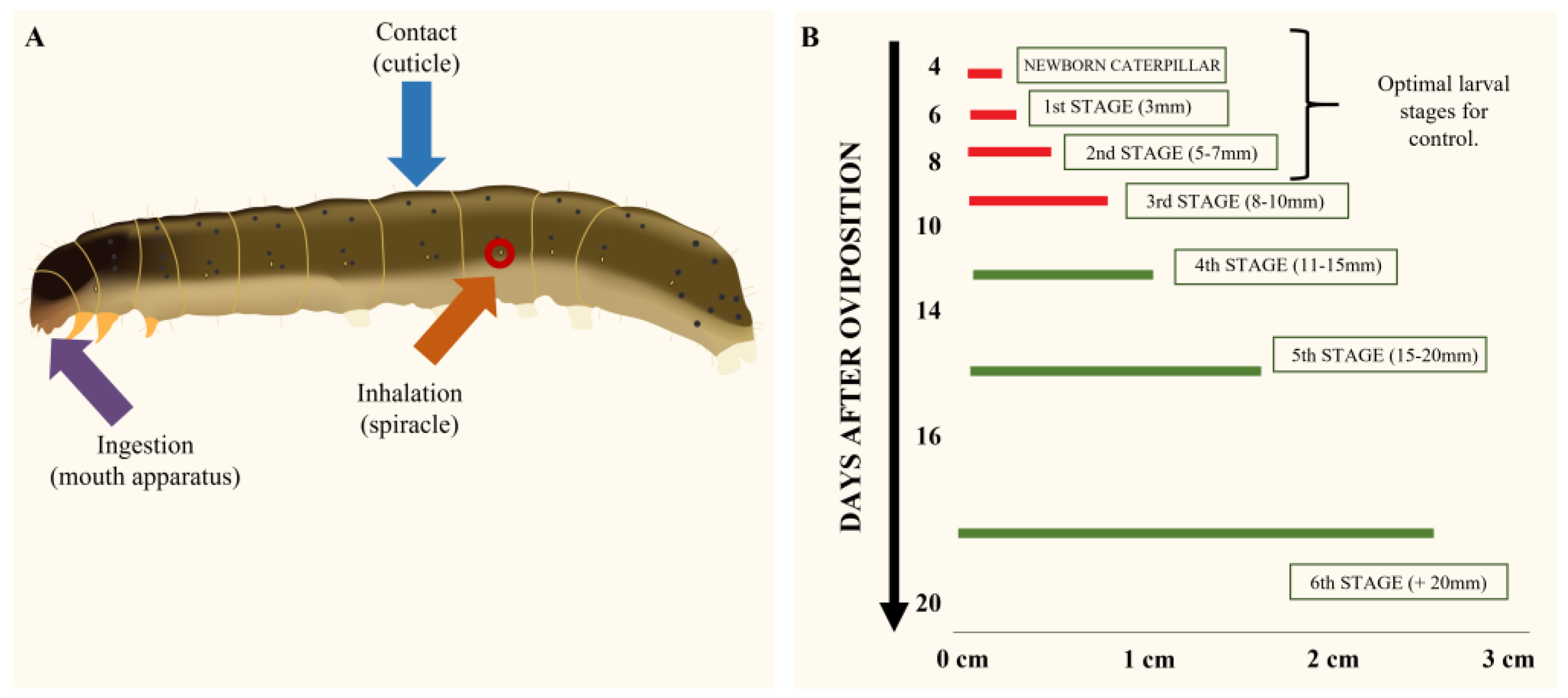

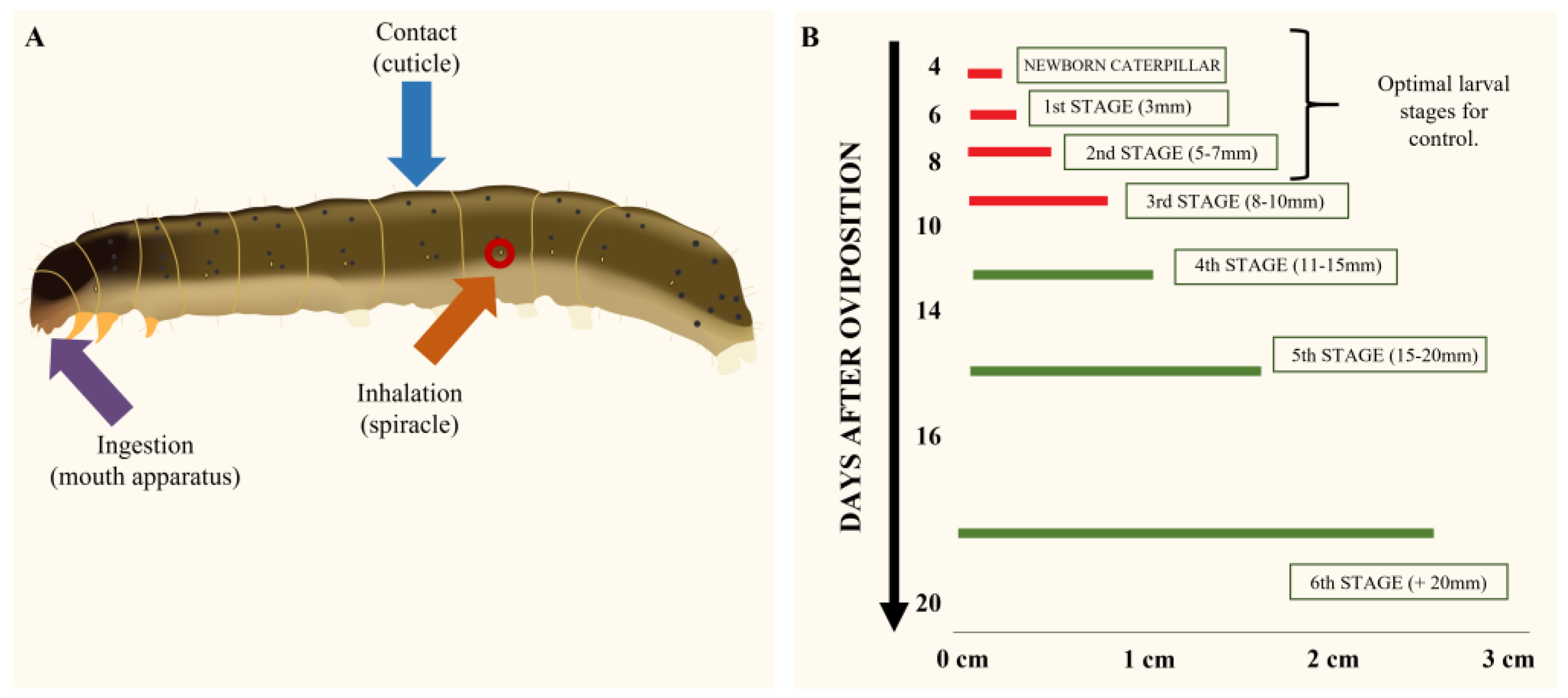

By considering the physicochemical properties of EOs, three main routes of access of these to the target insect could be determined (Figure 2A)—ingestion, inhalation and direct contact with the integument.

Figure 2. (A) Routes of entry of EOs to lepidopteran larvae. Orange arrow: entry through the respiratory spiracles. Purple arrow: entry through ingestion of treated food. Blue arrow: entry by direct contact with the integument. (B) Optimal moments of chemical control thought the larval stages of S. frugiperda. Red segments indicate the optimal stage for chemical control. (Modified from Programa Manejo de Resistencia de Insectos (MRI) and the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC Argentina) [47].)

The toxicity of EOs was mainly tested on larval stages (96%), while a few articles (4%) evaluated the toxicity on eggs. The FAW has six different larval stages (Figure 2B). Of these, 61% of the EO toxicity studies were carried out on the third stage, while the remaining ones were performed on the second (22%), first (14%) or fourth (3%) stages. There were no studies reporting EO toxicity being carried out on the fifth or sixth stage larvae. This is in agreement with numerous manuals about the control of S. frugiperda, which have indicated that 4 to 10 days after oviposition is the optimal time to apply chemical controls (Figure 2B) because the larvae are newly hatched, and also to minimize the damage that these insects can cause to the maize crop [48][49][50][51].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants12010003

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/news/world-population-prospects-2019-0 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- van Dijk, M.; Morley, T.; Rau, M.L.; Saghai, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Projected Global Food Demand and Population at Risk of Hunger for the Period 2010–2050. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 494–501.

- United States Departament of Agriculture. Foreign Agricultural Service. World Agricultural Production; United States Departament of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/production.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Pimentel, D. Integrated Pest Management: Innovation-Development Process. In Integrated Pest Management; Peshin, R., Dhawan, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 83–87. ISBN 978-1-4020-8991-6.

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Handa, N.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bali, A.S.; Parihar, R.D.; et al. Worldwide Pesticide Usage and Its Impacts on Ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1446.

- Andrews, K.L. The Wholworm Spodoptera frugiperda in Central America and Nerghboring Areas. Fla. Entomol. 1980, 63, 456–467.

- Cock, M.J.W.; Beseh, P.K.; Buddie, A.G.; Cafá, G.; Crozier, J. Molecular Methods to Detect Spodoptera frugiperda in Ghana, and Implications for Monitoring the Spread of Invasive Species in Developing Countries. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4103.

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wu, K. Spread of Invasive Migratory Pest Spodoptera frugiperda and Management Practices throughout China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 637–645.

- Shylesha, A.N.; Jalali, S.K.; Gupta, A.; Varshney, R.; Venkatesan, T.; Shetty, P.; Ojha, R.; Ganiger, P.C.; Navik, O.; Subaharan, K.; et al. Studies on New Invasive Pest Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Its Natural Enemies. J. Biol. Control 2018, 32, 145–151.

- Goergen, G.; Kumar, P.L.; Sankung, S.B.; Togola, A.; Tamò, M. First Report of Outbreaks of the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (J E Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a New Alien Invasive Pest in West and Central Africa. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165632.

- Deshmukh, S.; Pavithra, H.B.; Kalleshwaraswamy, C.M.; Shivanna, B.K.; Maruthi, M.S.; Mota-Sanchez, D. Field Efficacy of Insecticides for Management of Invasive Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on Maize in India. Fla. Entomol. 2020, 103, 221–227.

- Qi, G.J.; Ma, J.; Wan, J.; Ren, Y.L.; McKirdy, S.; Hu, G.; Zhang, Z.F. Source Regions of the First Immigration of Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Invading Australia. Insects 2021, 12, 1104.

- Lezaun, J. Gusano Cogollero: Una Plaga de Alto Impacto. Available online: https://www.croplifela.org/es/plagas/listado-de-plagas/gusano-cogollero (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Christou, P.; Capell, T.; Kohli, A.; Gatehouse, J.A.; Gatehouse, A.M.R. Recent Developments and Future Prospects in Insect Pest Control in Transgenic Crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 302–308.

- Machado, E.P.; Gerson, G.L.; Führ, F.M.; Zago, S.L.; Marques, L.H.; Santos, A.C.; Nowatzki, T.; Dahmer, M.L.; Omoto, C.; Bernardi, O. Cross-Crop Resistance of Spodoptera frugiperda Selected on Bt Maize to Genetically-Modified Soybean Expressing Cry1Ac and Cry1F Proteins in Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10080.

- Rabelo, M.M.; Matos, J.M.L.; Santos-Amaya, O.F.; França, J.C.; Gonçalves, J.; Paula-Moraes, S.V.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Pereira, E.J.G. Bt-Toxin Susceptibility and Hormesis-like Response in the Invasive Southern Armyworm (Spodoptera eridania). Crop Prot. 2020, 132, 105129.

- Szwarc, D.E. Dispersión y Mortalidad de Larvas de Spodoptera frugiperda S. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) en Híbridos de Maíz Convencional y Transgénico Bt. Potenciales Implicancias para el Manejo de la Resistencia. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina, 2018.

- Téllez-Rodríguez, P.; Raymond, B.; Morán-Bertot, I.; Rodríguez-Cabrera, L.; Wright, D.J.; Borroto, C.G.; Ayra-Pardo, C. Strong Oviposition Preference for Bt over Non-Bt Maize in Spodoptera frugiperda and Its Implications for the Evolution of Resistance. BMC Biol. 2014, 12, 48.

- Santos-Amaya, O.F.; Rodrigues, J.V.C.; Souza, T.C.; Tavares, C.S.; Campos, S.O.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Pereira, E.J.G. Resistance to Dual-Gene Bt Maize in Spodoptera frugiperda: Selection, Inheritance, and Cross-Resistance to Other Transgenic Events. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18243.

- Bernardi, D.; Salmeron, E.; Horikoshi, R.J.; Bernardi, O.; Dourado, P.M.; Carvalho, R.A.; Martinelli, S.; Head, G.P.; Omoto, C. Cross-Resistance between Cry1 Proteins in Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) May Affect the Durability of Current Pyramided Bt Maize Hybrids in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140130.

- Blanco, C.A.; Chiaravalle, W.; Dalla-Rizza, M.; Farias, J.R.; García-Degano, M.F.; Gastaminza, G.; Mota-Sánchez, D.; Murúa, M.G.; Omoto, C.; Pieralisi, B.K.; et al. Current Situation of Pests Targeted by Bt Crops in Latin America. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2016, 15, 131–138.

- Souza Ribas, N.; McNeil, J.N.; Días Araújo, H.; Souza Ribas, B.; Lima, E. The Effect of Resistance to Bt Corn on the Reproductive Output of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects 2022, 13, 196.

- Jacques, F.L.; Degrande, P.E.; Gauer, E.; Malaquias, J.B.; Scoton, A.M.N. Intercropped Bt and Non-Bt Corn with Ruzigrass (Urochloa ruziziensis) as a Tool to Resistance Management of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith, 1797) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 3372–3381.

- Hanif, M.A.; Nisar, S.; Khan, G.S.; Mushtaq, Z.; Zubair, M. Essential Oils. In Essential Oil Research; Malik, S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–17. ISBN 9783030165468.

- Dambolena, J.S.; Gallucci, M.N.; Luna, A.; Gonzalez, S.B.; Guerra, P.E.; Zunino, M.P. Composition, Antifungal and Antifumonisin Activity of Pinus wallichiana, Pinus monticola and Pinus strobus Essential Oils from Patagonia Argentina. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2016, 19, 1769–1775.

- Pizzolitto, R.P.; Jacquat, A.G.; Usseglio, V.L.; Achimón, F.; Cuello, A.E.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Dambolena, J.S. Quantitative-Structure-Activity Relationship Study to Predict the Antifungal Activity of Essential Oils against Fusarium verticillioides. Food Control 2020, 108, 106836.

- Brito, V.D.; Achimón, F.; Pizzolitto, R.P.; Ramírez Sánchez, A.; Gómez Torres, E.A.; Zygadlo, J.A.; Zunino, M.P. An Alternative to Reduce the Use of the Synthetic Insecticide against the Maize Weevil Sitophilus zeamais through the Synergistic Action of Pimenta racemosa and Citrus sinensis Essential Oils with Chlorpyrifos. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 409–421.

- Arena, J.S.; Peschiutta, M.L.; Calvimonte, H.; Zygadlo, J.A. Fumigant and Repellent Activities of Different Essential Oils Alone and Combined Against the Maize Weevil (Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky). MOJ Bioorg. Org. Chem. 2017, 1, 249–253.

- Giller, K.E.; Delaune, T.; Silva, J.V.; Descheemaeker, K.; van de Ven, G.; Schut, A.G.T.; van Wijk, M.; Hammond, J.; Hochman, Z.; Taulya, G.; et al. The Future of Farming: Who Will Produce Our Food? Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1073–1099.

- OECD-FAO. Perspectivas para el Medio Ambiente. In Agricultura Mundial: Hacia Los Años 2015/2030; Food and Agriculture Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Devrjna, N.; Milutinović, M.; Savić, J. When Scent Becomes a Weapon- Plant Essential Oils as Potent Bioinsecticides. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5847.

- Gołębiowski, M.; Stepnowski, P. Chemical Composition of Insect Surface Waxes: Biological Functions and Analytics. In Handbook of Bioanalytics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–19.

- Stamm, K.; Saltin, B.D.; Dirks, J.H. Biomechanics of Insect Cuticle: An Interdisciplinary Experimental Challenge. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2021, 127, 329.

- Singh, S.; Chaurasia, P.; Bharati, S.; Golla, U. A Mini-Review on the Safety Profile of Essential Oils. MOJ Biol. Med. 2022, 7, 33–36.

- Dutra, K.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; Guedes, C.; Cruz, G.; Navarro, D.; Monteiro, A.; Agra, A.; Lapa Neto, C.; Teixeira, Á. Toxicity of Essential Oils of Leaves of Plants from the Genus Piper with Influence on the Nutritional Parameters of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2020, 23, 213–229.

- Gad, H.A.; Hamza, A.F.; Abdelgaleil, S.A.M. Chemical Composition and Fumigant Toxicity of Essential Oils from Ten Aromatic Plants Growing in Egypt against Different Stages of Confused Flour Beetle, Tribolium confusum Jacquelin Du Val. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 697–706.

- Renoz, F.; Demeter, S.; Degand, H.; Nicolis, S.C.; Lebbe, O.; Martin, H.; Deneubourg, J.L.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Morsomme, P.; Hance, T. The Modes of Action of Mentha arvensis Essential Oil on the Granary Weevil Sitophilus granarius Revealed by a Label-Free Quantitative Proteomic Analysis. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 381–395.

- Gerolt, P. Mode of Entry of Contact. J. Insect Physiol. 1969, 15, 563–580.

- Sugiura, M.; Horibe, Y.; Kawada, H.; Takagi, M. Insect Spiracle as the Main Penetration Route of Pyrethroids. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2008, 91, 135–140.

- Balabanidou, V.; Grigoraki, L.; Vontas, J. Insect Cuticle: A Critical Determinant of Insecticide Resistance. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 27, 68–74.

- Pedrini, N.; Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Huarte-Bonnet, C.; Zhang, S.; Keyhani, N.O. Targeting of Insect Epicuticular Lipids by the Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria bassiana: Hydrocarbon Oxidation within the Context of a Host-Pathogen Interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 24.

- Karunaratne, P.; De Silva, P.; Weeraratne, T.; Surendran, N. Insecticide Resistance in Mosquitoes: Development, Mechanisms and Monitoring. Ceylon J. Sci. 2018, 47, 299.

- Mossa, A.T.H. Green Pesticides: Essential Oils as Biopesticides in Insect-Pest Management. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 354–378.

- Tak, J.H.; Isman, M.B. Enhanced Cuticular Penetration as the Mechanism for Synergy of Insecticidal Constituents of Rosemary Essential Oil in Trichoplusia Ni. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12690.

- Mwamburi, L.A. Role of Plant Essential Oils in Pest Management. In New and Future Development in Biopesticide Research: Biotechnological Exploration; De Mandal, S., Ramkuamar, G., Karthi, S., Jin, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; ISBN 9789811639883.

- Papachristos, D.P.; Stamopoulos, D.C. Repellent, Toxic and Reproduction Inhibitory Effects of Essential Oil Vapours on Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 2002, 38, 117–128.

- Programa Manejo de Resistencia de Insectos (MRI); Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC Argentina). Cogollero (Spodoptera frugiperda) en el Cultivo de Maíz: Bases para su Manejo y Control en Sistemas de Producción; REM AAPRESID: Rosario, Argentina, 2019; ISBN 9788578110796.

- Programa Manejo de Resistencia de Insectos (MRI); Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC Argentina). Cogollero (Spodoptera frugiperda) en el Cultivo de Maíz: Bases para su Manejo y Control en Sistemas de Producción; REM AAPRESID: Rosario, Argentina, 2019; ISBN 9788578110796.

- Ianonne, N.; Leiva, P. Guia Practica para el Cultivo de Maiz; Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2011.

- International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). Secretariat Prevention, Preparedness and Response Guidelines for Spodoptera frugiperda; International Plant Protection Convention: Rome, Italy, 2021.

- LG Semillas. GUÍA DE MANEJO: Spodoptera Frugiperda, Gusano Cogollero en Maíz; LG Semillas: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!