Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Others

The PDX-1, also known as IUF-1 (insulin upstream factor 1), IPF-1 (insulin promoter factor 1), STF-1 (somatostatin transcription factor 1), and IDX-1 (islet/duodenum homeobox-1), is a member of the homeodomain (HD)-containing transcription factor family and was first found in Xenopus laevis.

- PDX-1

- diabetes mellitus

- reversal

- transcription factor

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder with an increasing prevalence worldwide. It is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and disturbances in protein, carbohydrate, and fat metabolism due to insulin resistance (IR) and/or insulin secretion deficiency [1]. Approximately one billion people suffer from chronic hyperglycemia globally, a major public health problem. The International Diabetes Federation estimates that 10.5% (537 million) of adults aged 20–79 years are currently living with DM, and this prevalence is expected to increase to 11.3% (643 million) by 2030 and 12.2% (783 million) by 2045. With 1.541 million adults having impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), their risk for type 2 diabetes is increased [2]. Diabetes causes a series of complications, including blindness, renal failure, stroke, and coronary artery disease, resulting in a huge medical burden on society [3]. Furthermore, diabetes costs at least 966 billion dollars in health expenditure, a 316% increase over the last 15 years [2].

DM is divided into type 1 diabetes (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (T1DM or IDDM)), type 2 diabetes (non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (T2DM or NIDDM)), specific types of diabetes due to other causes, and gestational diabetes mellitus [4,5]. T2DM is the most common presentation of DM, accounting for approximately 90% of DM cases, whereas T1DM constitutes more than 5% [6,7]. T2DM is a chronic multisystem disease characterized by insulin resistance and elevated blood glucose levels [8]. It is the result of a complex interplay between genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors [9,10]. However, its etiology and pathogenesis have not yet been fully elucidated. The traditional view is that diabetes can only be controlled and not cured. Authoritative guidelines and clinical diabetes research mostly focus on controlling blood glucose levels and improving complications. Blood glucose levels are controlled by promoting insulin secretion, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and promoting glucose absorption by other tissues outside the islets of Langerhans [11,12]. With recent advances in diabetes research and medical technology progress, researchers have discovered new methods for preventing and treating diabetes with promising results. The terms “Diabetes reversal” and “Diabetes remission” have been used in scientific articles. They connote a glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level of <6.5% (<48 mmol/mol) for at least 3 months without the usual glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy [13]. The reversal strategy, mechanism, and predictors are becoming increasingly clear with further research [14,15,16,17]. One of the possible mechanisms of diabetes reversal is that the removal of excess fat in the liver and pancreas can normalize hepatic glucose production and β-cell redifferentiation [14]. However, more studies are needed on the mechanism of diabetes reversal.

Studies on the role of PDX-1 in reversing diabetes are on the increase. PDX-1 regulates pancreatic development, β-cell differentiation, and the maintenance of mature β-cell function [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Non-β-cell can be reprogrammed by the transcription factors PDX-1 and musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family A (MafA) into functional β-cell, which secretes insulin to restore blood glucose levels [25,26]. In contrast, β-cell-specific removal of PDX-1 resulted in pancreatic agenesis and severe hyperglycemia [27,28]. Thus, promoting PDX-1 expression can be an effective strategy to ameliorate β-cell dysfunction and diabetes progression, making PDX-1 a new target for developing anti-diabetic drugs.

2. Gene Structure and Location, Protein Molecular Structure, Distribution, and Expression of PDX-1

The PDX-1, also known as IUF-1 (insulin upstream factor 1), IPF-1 (insulin promoter factor 1), STF-1 (somatostatin transcription factor 1), and IDX-1 (islet/duodenum homeobox-1), is a member of the homeodomain (HD)-containing transcription factor family and was first found in Xenopus laevis [18,29,30,31,32]. It plays a key role in the genesis, development, and maturation of the pancreas and is also one of the factors necessary for maintaining normal pancreatic islet function.

2.1. Localization and Molecular Structure of PDX-1

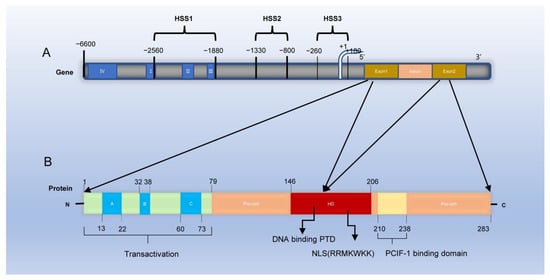

Rat and mouse PDX-1 genes are localized on chromosomes 12 and 5, respectively, whereas the human PDX-1 gene is located on chromosome 13q12 (12.1) [33,34,35,36]. The human PDX-1 gene is approximately 6 Kb long with two exons. The first exon encodes the NH2-terminal region and some HD, while the second encodes the remaining HD and the COOH-terminal domain [37]. (Figure 1) Three nuclease-hypersensitive sites were identified within the 5′-flanking region of the endogenous PDX-1 gene: HSS1(−2560~−1880 bp), HSS2(−1330~−800 bp), and HSS3(−260~+180 bp) [38].Among them, HSS1 is an important functional region of PDX-1 gene transcription activation and includes four sub-regions, region I (−2694~−2561 bp), region II (−2139~−1958 bp), and region III (−1879~−1799 bp). The fourth distal enhancer element is region IV, located between −6200 and −5670 bp [39,40,41]. Regions I and II endow endocrine cell expression, region Ⅲ mediates embryonic pancreas-wide expression, and region IV endows pancreas β-cell-specific gene expression and enhancement of proximal enhancer activity [42]. In addition, PDX-1 transcription is also regulated by factors acting upon conserved Area Ⅰ and IV sequences [38]. The proximal and distal promoters contain four conserved regions: I, II, III, and IV, which bind to various transcription factors to regulate cell differentiation [40]. In a study, a child’s pancreas did not develop (pancreatic agenesis) because the child was homozygous for an inactivating cytosine deletion in the protein-coding sequence of PDX-1 (pro63fsdelc), which indicated that PDX-1 might be associated with Type 2 diabetes [43]. In addition, six novel PDX-1 missense mutations (C18R, D76N, R197H, Q59L, G212R and P2390) were identified in patients with type 2 diabetes [44,45].

Figure 1. Structure of PDX-1 gene and protein. (A) PDX-1 gene contains two exons: exon 1 encodes the NH2-terminal domain and some homeodomain of PDX-1 protein, and exon 2 encodes the remaining homeodomain and COOH-terminal domain. Three nuclease-hypersensitive sites were identified within the 5′-flanking region of the endogenous PDX-1 gene: HSS1 (−2560~−1880 bp), HSS2 (−1330~−800 bp) and HSS3 (−260~+180 bp). Among them, HSS1 is an important functional region of PDX-1 gene transcription activation and includes four sub-regions, region I (−2694~−2561 bp), region II (−2139~−1958 bp), region III (−1879~−1799 bp), and region IV (−6200 and −5670 bp). (B) PDX-1 protein comprises 283 amino acids. The NH2-terminal is a proline-rich transcriptional activation domain, including 1~77 amino acids (amino acid AA or aa), which is composed of three highly conserved subdomains A, B, and C (A:13−22aa B:32−38aa C:60−73aa). The homeodomain (HD) is composed of 146~206 amino acids, which contains three highly conserved helical regions: helix1, helix2, and helix3 (H1 H2 H3); the nuclear localization signal (NLS) is part of H3. The COOH-terminal is composed of 238~283 amino acids, and the conserved motif (210~238 amino acids) mediates the interaction of PDX-1-PCIF1 (PDX-1 C-terminal interacting factor-1) and inhibits the transcriptional activity of PDX-1.

The human PDX-1 protein comprises 283 amino acids with a predicted molecular weight of 30.77 KDa [46]. The PDX-1 activation domain is contained within the NH2-terminal, its HD is involved in DNA binding, and they both participate in protein–protein interactions [47]. Point mutation analysis showed that the transcriptional activation region was necessary to activate insulin gene transcription [48]. The HD contains the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and an Antennapedia-like protein transduction domain (PTD), the nuclear import of PDX-1 depends on the NLS motif RRMKWKK [49]. PDX-1 mainly exists in the cytoplasm or around the nucleus in the resting state. Changes in the external environment, such as ionizing radiation and the increase in glucose concentration, can activate PDX-1 and translocate it into the nucleus [50]. The NLS of transcription factors is a crucial requirement for its action, possibly because free PDX-1 is modified by phosphorylation, acetylation, and sumoylation, which exposes the NLS and guides the nuclear translocation of PDX-1 [51,52,53]. In addition, Guillemain G et al. found that PDX-1 first interacts with the nuclear input receptor importinβ1 to form a complex; importinβ1 then interacts with the nuclear pore complex on the nucleus surface. It mediates PDX-1 entry into the nucleus. Ras-related nuclear protein (Ran) GTP and importinβ1 dissociate in the nucleus, followed by the reflux of the Ran GTP and importinβ1 complex into the cytoplasm through nuclear pores. Ran GTP is transformed into Ran, GDP, and the dissociated cytoplasm importinβ1 continues to participate in the transport of transcription factors [54]. In addition, it was previously reported that exogenous PDX-1 protein can permeate cells and induce insulin gene expression in pancreatic ducts because its own antennapedia-like protein transduction domain (PTD) sequence in its structure can bind to the insulin promoter and activate its expression [55]. A conserved motif at the C-terminal of PDX-1 mediates the interaction of PDX-1-PCIF1(PDX-1 C-terminal interacting factor-1) and inhibits the transcriptional activity of PDX-1 [56]. In addition, Humphrey et al. reported a novel functional role for the PDX-1 C-terminus in mediating glucose effects. They demonstrated that glucose modulates PDX-1 stability via the AKT-GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase 3) axis [57]. Therefore, PDX-1 has a dual function. First, it promotes early pancreatic development and late β-cell differentiation. Second, it maintains the morphology and normal function of mature β cells, especially the normal expression of insulin secretion genes.

2.2. Tissue Distribution and Expression of PDX-1

PDX-1 expression in cells at different stages is inconsistent. In the early developmental stage, PDX-1 widely exists in the cell population transformed into endocrine and exocrine parts of the pancreas and some brain cells in the embryonic stage. However, PDX-1 is highly expressed in β, δ, and endocrine cells of the duodenum following maturation. In contrast, its expression is low in some ductal and acinar cells [58,59]. Stoffers et al. found that PDX-1 played an important role in developing the exocrine and endocrine portions of the pancreas, pancreatic ducts, pyloric glands of the distal stomach, common bile and cystic ducts, the intestinal epithelium of the duodenum, Brunner’s glands, and the spleen [60]. In addition to the gastrointestinal system, PDX-1 is expressed in embryonic brain cells during the active nervous system generation phase [61]. Researchers have reported PDX-1 overexpression in various human tumor tissues [62,63,64]. Wang XP et al. used tissue microarray and immunohistochemical techniques to demonstrate PDX-1 overexpression in breast, kidney, pancreatic, and prostate cancers. They suggested that PDX-1 was probably one of the early markers of tumorigenesis [65].

3. Factors Regulating PDX-1 Expression

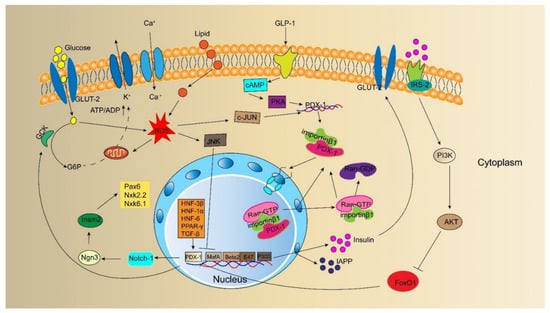

PDX-1 is critical for maintaining β cells, and its downregulation results in β-cell dedifferentiation. The induction of PDX-1 expression maintains mature and functional β cells. The regulation of PDX-1 gene expression is a complex process (Figure 2) involving nutrient substances, hormones, oxidative stress, and cytokines.

Figure 2. Model outlining upstream regulator and direct downstream target of PDX-1 and the insulin signaling pathway involved by PDX-1. It has been identified that glucose, lipid, GLP-1, ROS, and other cytokines, such as FoxO1, HNF-3β, HNF-6, PPAR-γ, TGF-β, can directly regulate the expression of PDX-1. PDX-1 regulates the expression of insulin, GCK, GLUT-2, IAPP to maintain β-cell characteristics and functions. In addition, PDX-1 involves the signaling pathway of insulin secretion.

3.1. Nutrient Substances

Glucose and fatty acids regulate PDX-1 expression. Many studies elucidated the underlying molecular mechanisms of glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. In adult islet β-cell, a short-term hyperglycemic environment promotes the combination of PDX-1 and insulin genes and improves insulin mRNA levels. However, PDX-1 and insulin levels decrease under the cytotoxic effect of long-term hyperglycemia [66]. The inhibition of PDX-1 expression by high glucose concentration is one of the mechanisms of glucotoxicity. Furthermore, chronic hyperglycemia has been reported to deteriorate β-cell function by inducing oxidative stress and reducing PDX-1 DNA-binding activities [67]. In addition to activating the DNA-binding activity of PDX-1, glucose also affects PDX-1 phosphorylation, PDX-1 distribution between the nuclear membrane and nucleoplasm, and the transactivation potential of the amino-terminal active region of PDX-1; however, its mechanism of action remains unclear. High fatty acid concentrations also inhibit PDX-1 expression. Gramlich et al. showed that the co-culture of pancreatic islets with palmitic acid reduced mRNA and protein expression levels of PDX-1 by 70%. The binding force between PDX-1, glucose transporter 2 (GLUT-2), and the insulin gene promoter decreased by 40–65% [68]. The prolonged exposure of islets to palmitate inhibits insulin gene transcription by impairing the nuclear localization of PDX-1 [69]. Shimo N et al. found that PDX-1 expression was significantly reduced during glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. After treatment with empagliflozin or bezafibrate to selectively improve glucotoxicity or lipotoxicity, PDX-1 showed significantly higher expression levels and enhanced β-cell proliferation [70]. The study provided further evidence that glucose and fatty acids regulate PDX-1 expression.

3.2. Hormones

The incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is produced by gut endocrine L cells in a nutrient-dependent manner and secreted in pancreatic islets [71]. Studies have shown that GLP-1 is involved in regulating PDX-1. Wang et al. found that GLP-1 promotes PDX-1 expression in a glucose-dependent manner, increases its intracellular protein content and improves its binding activity with the A1 region of the insulin gene. Simultaneously, GLP-1 activates adenosine cyclase, increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) content in cells, and activates protein kinase A (PKA), which promotes PDX-1 synthesis and increases its content [72,73]. Hwang SL et al. found that treating rat insulinoma cells with GLP-1 significantly increased β-cell translocation gene 2 mRNA expression in dose- and time-dependent manners and subsequently elevated PDX-1 and insulin mRNA levels in pancreatic β cells [74]. The activation of PKA induced by GLP-1 increases PDX-1 level and translocation to the nucleus, where PDX-1 binds to the insulin gene promoter to initiate insulin expression and synthesis [75]. In addition, the runaway signal system of the small Ran GTPase significantly downregulates PDX-1 expression in postnatal mice, resulting in insulin deficiency, decreased cell proliferation rate, and diabetes [76]. In aging animal models of type 2 diabetes, the expression of the PDX-1 gene was decreased, the number of β cells was reduced, and the long-term use of GLP-1 reversed these pathological changes. However, when exendin (9–39) (a specific antagonist of GLP-1) was infused, its effects on the levels of PDX-1 messenger RNA were eliminated [77]. These studies showed that GLP-1 stimulates pancreatic cell proliferation and β-cell differentiation by regulating PDX-1.

3.3. Oxidative Stress

Some studies have shown that reactive oxygen species (ROS) reduce PDX-1 mRNA synthesis, leading to a decline in PDX-1 synthesis and a reduction in the binding of PDX-1 to the insulin gene promoter and the transcription of the insulin gene. Cannabinoids have strong antioxidant properties. Baeeri et al. used 10 μM cannabidiol and tetrahydrocannabinol to treat aged rat islet cells. The results showed that the percentage of ROS was significantly reduced with the elevation of PDX-1 expression and insulin release [78]. However, the results were preliminary, and further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism. Leenders et al. treated human islets with 200 μM hydrogen peroxide for 90 min and found that the gene and protein expression of the key transcription factor PDX-1 was reduced by over 60% [79]. Furthermore, Matsuoka et al. treated HIT-T15 cells cultured in vitro with the oxidative stress inducer d-ribose. They found that PDX-1 expression in cells was reduced, and the binding of PDX-1 to the insulin gene promoter was significantly reduced. However, 1 mM aminoguanidine or 10 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) prevented the effects of d-ribose [80]. Kawamori et al. also found that oxidative stress affects the nucleocytoplasmic translocation of PDX-1 by activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and pointed out that JNK may induce the translocation of PDX-1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by activating the nuclear output signal of PDX-1, reducing the expression of PDX-1 in the nucleus, and also reducing insulin synthesis and secretion [81,82]. After treating diabetes mice (C57BL/KsJ-db/db) with antioxidant drugs (NAC), Kajimoto et al. found that the expression of PDX-1 in the nucleus of pancreatic islets was significantly increased, and the amounts of insulin content and insulin mRNA were preserved [83]. Nucleocytoplasmic translocation of PDX-1 is the key to promoting insulin secretion. Oxidative stress can affect the nucleocytoplasmic translocation of PDX-1, reduce the interaction between PDX-1 and insulin gene promoters, and reduce insulin synthesis and secretion. Baumel-Alterzon S et al. reported that the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) antioxidant pathway controls the redox balance and allows the maintenance of high PDX-1 levels; pharmacological activation of the Nrf2 pathway may alleviate diabetes by preserving PDX-1 levels [84].

3.4. Cytokines

Many cytokines (hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF-3β), HNF-6, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ)) act upstream of PDX-1 in the regulatory hierarchy governing pancreatic development. HNF-3β (also named Foxa2) is a transcription factor in the HNF family. HNF-3β binds to multiple sites in the transcriptional activation functional region of the PDX-1 gene and recruits other transcription factors to the regulatory region to enhance gene transcription [85]. In addition, co-transfection experiments suggested that HNF-3β, HNF-1α, and specificity protein 1 (Sp1) are positive human PDX-1 enhancer elements with mutual coordination [86]. Gao et al. found that compound conditional ablation of Foxa1 and Foxa2 caused near severe pancreatic hypoplasia and total loss of PDX-1 expression, and Foxa2 appeared to predominate. Jacquemin et al. also found that HNF-6 acted upstream of PDX-1 during the development of the pancreas, and HNF-6(-/-) mice were hypoplastic [87]. Sayo et al. used the TGF-β to process pancreatic β cells, and the results showed that TGF-β activates the insulin gene by activating PDX-1 [88]. PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone was reported to increase the immunostaining of PDX-1 and Nkx6.1, while PPAR-γ inhibitors reduced the mRNA levels of PDX-1 through RNA interference [89]. In addition, the study found that PDX-1 interacted with the p300 coactivator, β-cell E-box transcription factor (BETA2), and E47 coactivator to mediate insulin gene transcription [58]. These cytokines play a significant role in developing the pancreas; however, further studies are needed to explore their regulation to ensure PDX-1 transcription.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12121785

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!