Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

A vegan diet tends to be plant-based, but plant-based diets are not vegan by definition. Regarding Alzheimer’s disease (AD) prevention, a vegan diet includes low levels of saturated fats and cholesterol, contributing to a healthy blood lipid profile.

- vegan diet

- Alzheimer’s disease

- cognition

1. Introduction

In recent years, a vegan diet has grown in popularity worldwide. According to a survey conducted in 2021, vegans represent about 2–3% of the population in European countries [1]. The complex effect of a vegan diet on mortality, health, and environmental outcomes was also reflected by the recommendation for a sustainable diet strategy based on the survey from 150 countries worldwide, where a vegan diet turned out to be the most effective for the followed parameters as compared to vegetarian, pescatarian, and flexitarian diets [2].

Neurodegenerative disorders are also on the rise worldwide. It was estimated that more than 50 million people worldwide lived with dementia in 2019, which is expected to triple in 30 years, reaching 152 million in 2050 [3]. AD is the leading cause of dementia, and its prevalence is growing rapidly, making it a major public health issue. The onset of AD is predicted by several risk factors, which are both genetic and modifiable. Non-modifiable risk factors include advanced age [4][5][6], gender [5][6], a family history of dementia, and genetic susceptibility [4]. AD is also associated with modifiable risk factors, such as depression [7][8][9], hypertension [10][11][12], type 2 diabetes [13][14][15], obesity [16][17][18], physical inactivity [19][20], low education [4][5][21], and unhealthy diet [22][23]. Even though there is currently no cure for AD, people can reduce their risk by addressing the modifiable risk factors. One of the key lifestyle factors that can be modified to prevent AD is diet.

2. Vegan Diet and Brain Function

Nutrition plays a crucial role in maintaining proper brain function as we age. Researchers have been increasingly studying the role of dietary and lifestyle factors, such as plant-based diets, in AD [23]. Brain health was found to be improved by diets such as the Mediterranean, Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND), or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH). Adhering to the Mediterranean, DASH, or MIND diet can decrease cognitive decline and AD risk [24][25][26]. What these diets have in common is that they limit sugar and saturated fat intake and recommend eating a high percentage of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts and consuming minimal amounts of red or processed meat. Several medical organizations have recommended a plant-based diet to optimize cognitive health and potentially prevent dementia [27][28][29]. To maintain cognitive health and prevent cognitive aging, consuming a plant-based diet can be a low-risk and beneficial lifestyle change.

However, plant-based and vegan diets are not synonymous. A vegan diet tends to be plant-based, but plant-based diets are not vegan by definition. In a plant-based diet, plants are the primary component, but animal products are also included in small amounts. A whole-food, plant-based diet is centered on whole, unrefined plant foods and minimizes highly refined foods, such as bleached flour, refined sugar, oil, and processed packaged foods [30]. A vegan diet entirely abstains from animal products and is a stricter version of vegetarianism. In addition to cutting out meat, vegans eliminate everything made or derived from an animal, including dairy, eggs, and honey. Additionally, vegans refrain from using animal products in other areas of their lives, including beauty products, footwear, and clothing [31].

The effects of a plant-based diet on brain health and cognition are well documented. A vegan diet seems effective for various outcomes, ranging from weight loss to cardiometabolic health [32] to reduced cancer incidence [33].

3. Possible Beneficial Effects of a Vegan Diet on the Brain and the Risk of AD

3.1. Fruits and Vegetables

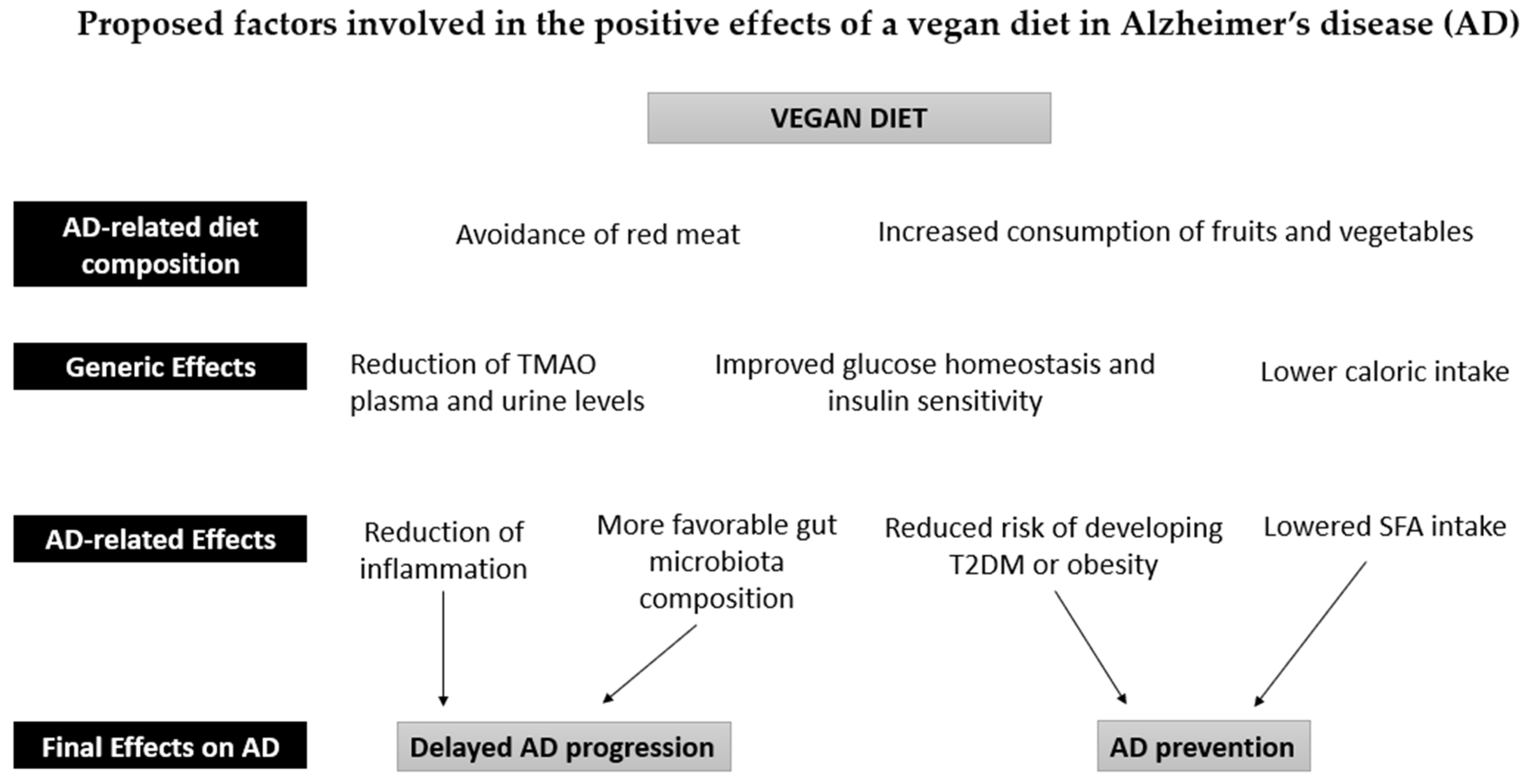

Vegetables, fruits, grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds constitute the bulk of a vegan diet. Several meta-analyses have found that the increased consumption of fruits and vegetables can reduce dementia risk and slow down cognitive decline in older adults [34][35][36]. Conversely, a low vegetable intake is associated with poorer cognition in AD dementia [37]. A high intake of fruits and vegetables could therefore act as secondary prevention in AD. Furthermore, the phytochemicals, vitamins, minerals, and fiber found in fruits and vegetables have well-established anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which may protect the brain by reducing the pathological processes associated with aging and dementia [38] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proposed factors involved in the positive effects of a vegan diet in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The intake of fruits and vegetables in a vegan diet is associated with a reduction in inflammatory processes and a normalization of the gut microbiota due to the high antioxidant, fiber, and polyphenol content. The absence of red meat also leads to a reduction in Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in plasma and urine. These effects can counteract the development of AD pathology. Furthermore, the reduction in caloric intake reduces the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2DM), thus contributing to the prevention of AD, together with the reduced intake of saturated fatty acids (SFA).

3.2. Reduction in Inflammation

Inflammation plays an important role in the development of AD. Inflammatory cascades may contribute to AD pathogenesis when the amyloid beta (Aβ) levels are continuously high, mobilizing the innate immune system through microglia activation [39]. Patients with AD often present with high levels of inflammatory markers, and these markers are linked to cognitive decline as well [40][41].

Part of the protective mechanisms of a vegan diet could be attributed to its beneficial effect on the reduction of inflammatory markers (Figure 1), thus acting as secondary prevention in AD. It appears that meat-based dietary patterns are positively correlated with biomarkers of low-grade inflammation, while vegetable- and fruit-based diets are inversely correlated [42]. However, studies providing data on inflammatory biomarkers in vegans are sparse and inconsistent. In a cross-sectional study of 36 vegans and 36 omnivores, Menzel et al. found no significant differences in any of the seven investigated inflammatory biomarkers (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), adiponectin, ICAM-1, IL-18, IL-1 RA, omentin-1, and resistin). The participants that adhered to the vegan diet for over 4.8 years were more likely to have lower hsCRP levels compared to those adhering to a vegan diet for less than 4.8 years [43], suggesting the length of the diet may be an essential factor in reducing systemic inflammation. Šebeková et al. also found that plasma CRP levels did not differ significantly between vegans and omnivores [44]. In contrast, Franco de Moreaes et al. detected lower values of inflammatory markers, CRP, and the TNF-α/IL-10 ratio in strict vegetarians (defined as consuming animal products less than once a month) compared to vegetarians and omnivores [45]. Suttlife et al. found reductions in the circulating CRP after a three-week lifestyle intervention that included a vegan diet [46]. Because the study included only overweight and obese participants, the decline in the CRP level between the baseline and follow-up could have been a result of various factors. The reduction in the body mass index was probably the most influential because overweight and obesity are associated with high levels of inflammation [47]. Researchers found that participants following a vegan diet prior to the intervention had the most favorable CRP profiles compared to vegetarians and omnivores [46], which may hint at the fact that a vegan diet may help to reduce inflammatory processes. Finally, a recent meta-analysis concluded that vegans have lower levels of CRP than omnivores [48].

Despite these data, the evidence regarding the effect of a vegan diet on inflammatory biomarkers is still limited. The majority of studies examining inflammatory biomarkers in vegans have small sample sizes and are cross-sectional, so causality cannot be determined. So far, only one vegan intervention study has been conducted, and because the participants were overweight, generalizing to other populations was not possible [46].

3.3. Modifiable Risk Factors for AD

Other than genetic factors, hypertension [10][11][12], diabetes [13][14][15], obesity [16][17][18], and midlife elevated blood lipids [49][50][51][52] all increase the AD dementia risk. All these AD risk factors can be modified through a vegan diet; therefore, a vegan diet can also aid in the primary prevention of AD. As a whole, a vegan diet can indirectly improve cognition by maintaining a healthy body weight and by reducing cardiovascular risk factors, such as cholesterol [33], blood glucose [53], and blood pressure [54]. Furthermore, a vegan diet might be a valuable tool for preventing diabetes [55]. Vegan diets have a lower energy content, making the people adopting them more likely to have a healthier body mass index (BMI) and lower obesity rates than those following other diets [33][56]. Low BMIs, maintained on the vegan diet, likely contribute to improved lipid profiles, glycemic results, and insulin sensitivity.

A vegan diet influences nutrient intake in several ways, which may ultimately affect insulin sensitivity. A vegan diet increases the intake of protective nutrients, such as polyphenols [57]. Dietary polyphenols inhibit glucose absorption in the intestine, stimulate insulin secretion, and enhance insulin-dependent glucose uptake [58]. The glucose-lowering effect of a vegan diet may also be attributed to the higher fiber content. Soluble dietary fiber improves glycemic control by delaying gastric emptying and the consequent slower glucose absorption and uptake [55]. Additionally, both soluble and insoluble fiber consumption can result in improved glycemic control by increasing insulin sensitivity [59]. A low-fat vegan dietary intervention leads to lower intramyocellular and hepatocellular lipid storage and thus increased insulin sensitivity [60].

3.4. GI Tract

A growing body of research shows that the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in AD pathogenesis [61][62][63]. The gut microbiome of AD patients is compositionally different, and it has a decreased diversity compared with those of cognitively unimpaired people [64]. Interactions between the intestine and the brain are mediated by the nervous system or by chemical substances crossing the blood–brain barrier [65]. A dysbiotic gut microbiome may contribute to the progression and exacerbation of the disease, possibly by promoting immune activation, systemic inflammation, Aβ aggregation, and insulin resistance in the periphery and the brain [63].

The ability to target the gut microbiota and restore its composition through food-based therapy may provide new preventive and therapeutic options for AD. Diet is among the key factors affecting the gut microbiota ecosystem [66]. A vegan diet differs from an omnivorous diet in terms of its macronutrient composition. The protein, total fat, and saturated fat intake is lower, while the carbohydrate and fiber intake is higher on a vegan diet [56][67]. The macronutrient balance alters the composition of the gut microbiota and, in turn, affects the production of metabolites that may have a positive or negative effect on health. A vegan diet seems to promote a more diverse gut microbiome and a more even distribution of microbial species [68]. The diversity and stability of the vegan gut microbiota are primarily attributed to a higher intake of complex carbohydrates, fiber, and polyphenols [56][69]. However, researchers have reported mixed results about how exactly a vegan diet affects the microbiome and its diversity. A short-term, four-week vegan diet intervention in omnivorous participants that were randomized to a vegan or an omnivorous diet led to no remarkable changes in their gut microbiota [70]. No significant difference between the alpha diversity of the subjects on the vegan or omnivore diet was observed; there were, however, changes in the abundance of the genera Coprococcus, Roseburia, and Blautia after the trial, but most of them were only detectable in a few of the samples [70]. Coprococcus, which was enriched in a vegan diet and depleted in an omnivore diet [70], was previously reported to be depleted both in the gut microbiota of 3xTg-AD mice [71] and in the fecal microbiota of AD patients and positively correlated with Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores [72]. Prochazkova et al. also found only modest differences in the microbiome composition associated with a long-term vegan vs. omnivore diet [73].

A recent systematic review of cross-sectional studies concluded that most studies report an increased abundance of Bacteroidetes on the phylum level and a higher abundance of Prevotella on the genus level in vegans compared to omnivores [74]. Prevotella is one of the fiber-utilizing bacterial species that ferments fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs are among the most abundant metabolites of the gut microbiota, and they play a crucial role in mediating gut–brain interactions. Their presence has been implicated in the occurrence and development of AD, and they play an important role in the disease process by regulating the synaptic plasticity, reducing the Aβ and tau pathology, and neuroinflammation [75]. In fecal samples, SCFAs decrease progressively from amnestic mild cognitive decline (MCI) to AD [76]. A vegan diet should in theory result in higher concentrations of SCFAs due to the increased intake of fiber, but the results of the studies are not unanimous. While Prochazkova et al. found a higher concentration of SCFAs in vegan fecal and serum metabolome [73], Trefflich et al., Wu et al., and Reiss et al. observed no significant differences in the fecal SCFA concentrations between vegans and omnivores [77][78][79]. While De Filippis et al. found that a vegan diet produced greater quantities of SCFAs, they also found a positive correlation between the SCFAs levels and adherence to a Mediterranean diet also in omnivores, irrespective of the diet type [80].

The vegan gut microbiota may also provide health benefits by reducing inflammation because it has been found to contain fewer pathobionts associated with low-grade inflammation [74]. Cattaneo et al. found that Aβ-positive AD patients have more pro-inflammatory bacteria in the gut than healthy controls and Aβ-negative patients. The inflammatory state, cognitive impairment, and Aβ presence in the brain were all positively related to the presence of pro-inflammatory microorganisms in the gut [81].

There is still some uncertainty about whether or not it leads to a more protective, healthier gut microbiota [74]. It seems that a vegan diet could be beneficial for the gut microbiota, although individual responses vary [70]. Despite the similarity between the gut microbiota of vegans and omnivores, their metabolomic profiles are quite different [73][78]. Veganism reduces the abundance of potentially harmful metabolites and increases the abundance of beneficial metabolites [73]. There is a need for further research to clarify the complicated mechanisms and interactions between the vegan diet, gut microbiota, and the subsequent effect of the diet on the pathophysiology and development of AD. Diet diversity is a critical driver of microbiota stability, and as such, it might be more essential to consume a variety of plant-based foods rather than to exclude animal products [82].

3.5. TMAO Reduction

Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) is the product of a microbial metabolite that increases with red meat consumption and has been linked to neurological diseases [68][69][82]. It was shown that the accumulation of tau and Aβ in the brain may be enhanced by TMAO. TMAO is capable of controlling the folding and aggregation state of the Aβ and accelerating its random coil-to-β-sheet conformational change, which is essential for the formation of Aβ fibers, thus accelerating the amyloidogenic plaque formation [83]. Accordingly, in AD and MCI patients, elevated cerebrospinal fluid TMAO levels correlate positively with the biomarkers of AD pathology and neurodegeneration [84], suggesting that TMAO may contribute to AD pathology. A possible mechanism by which TMAO could contribute to the development of AD is through the exacerbation of neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory processes. Additionally, TMAO has the potential to contribute to AD by stimulating insulin resistance and other metabolic disturbances associated with AD pathophysiology [85]. An increase in plasma TMAO has been shown to promote brain aging and cognitive impairment and to worsen AD by reducing the neurite density and increasing the synaptic damage in mice [86][87]. Conversely, reducing the TMAO levels in plasma has been shown to ameliorate cognitive decline in a mouse model of AD [88].

Vegan diets decrease the TMAO levels in plasma and urine, thus acting as a secondary prevention in AD, while diets high in animal protein have a negative effect [89]. In an interventional study investigating the impact of a vegan diet, the TMAO levels decreased after only eight weeks of consuming a vegan diet [90]. It has also been shown that following the consumption of L-carnitine, trimethylamine that is abundant in red meat, TMAO is produced in greater quantities by the intestinal microbiota of omnivores compared to vegetarians and vegans [91]. However, the plasma concentrations of TMAO between lacto-ovo-vegetarians and vegans do not seem to differ [92], suggesting that a vegetarian diet might be also powerful enough to lower TMAO levels.

3.6. Mental Health

Mental health could be an important factor to prevent AD insurgence. In the case of problems associated with mental health, it is possible that the risk of getting AD will increase. Factors such as chronic stress and depression can in fact increase the risk of developing AD [7][8][9]. In this regard, there is some light evidence that a vegan diet positively affects mental health and well-being, thus acting as primary prevention in AD.

Systemic reviews on the association between a vegan diet and depression reveal conflicting evidence, possibly due to the heterogeneity of the studies included. Thus, the pitfall of the existing studies is that the causal effect between depression and a vegan diet cannot be depicted [93].

Another meta-analysis found an association between a vegan diet and lower scores of anxiety [94]. The only intervention study with a raw vegan diet reported improvement in the overall QOL by 11.5% (p = 0.001), a decrease in anxiety by 18.6% (p = 0.009), and perceived stress by 16.4% (p < 0.001) after 12 weeks [95].

Possible mechanisms for the effects of a vegan diet in reducing depression and/or anxiety could be related to the action of quercetin, which is found only in plant foods [96]. Quercetin acts as an inhibitor of monoamine oxidase (MAO), an enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitters regulating mood, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine [97]. Thus, by acting as a sort of natural antidepressant, quercetin can increase the amount of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the brain [98], an effect that can mitigate anxiety and depression. In addition to its antidepressant properties, it was shown that quercetin exerts a neuroprotective effect in AD animal models. Mice treated with quercetin show a significant improvement in cognitive performance [99]. As a neuroprotective agent, quercetin inhibits Aβ aggregation and tauopathy [100], reduces oxidative stress and inflammation [101], and stimulates neurogenesis and neuronal plasticity by increasing the BNDF/TrkB signaling [102].

Conversely, arachidonic acid, which is found mostly in animal food, increases inflammation in the body [103], which is subsequently associated with feelings of anxiety, stress, and depression.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms232314924

References

- Share of Vegans in European Countries. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1256518/share-of-vegans-in-european-countries/ (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and Nutritional Aspects of Sustainable Diet Strategies and Their Association with Environmental Impacts: A Global Modelling Analysis with Country-Level Detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e451–e461.

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125.

- Lindsay, J.; Laurin, D.; Verreault, R.; Hébert, R.; Helliwell, B.; Hill, G.B.; McDowell, I. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: A Prospective Analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 156, 445–453.

- Zhang, M.; Katzman, R.; Salmon, D.; Jin, H.; Cai, G.; Wang, Z.; Qu, G.; Grant, I.; Yu, E.; Levy, P.; et al. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in Shanghai, China: Impact of age, gender, and education. Ann. Neurol. 1990, 27, 428–437.

- Brookmeyer, R.; Evans, D.A.; Hebert, L.; Langa, K.M.; Heeringa, S.G.; Plassman, B.L.; Kukull, W.A. National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 61–73.

- Green, R.C.; Cupples, L.A.; Kurz, A.; Auerbach, S.; Go, R.; Sadovnick, D.; Duara, R.; Kukull, W.A.; Chui, H.; Edeki, T.; et al. Depression as a Risk Factor for Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 753–759.

- Ownby, R.L.; Crocco, E.; Acevedo, A.; John, V.; Loewenstein, D. Depression and Risk for Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 530.

- Cantón-Habas, V.; Rich-Ruiz, M.; Romero-Saldaña, M.; Carrera-González, M.D.P. Depression as a Risk Factor For Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 457.

- Lennon, M.J.; Makkar, S.R.; Crawford, J.D.; Sachdev, P.S. Midlife Hypertension and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 71, 307–316.

- Rajan, K.B.; Barnes, L.L.; Wilson, R.S.; Weuve, J.; McAninch, E.A.; Evans, D.A. Blood Pressure and Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia by Antihypertensive Medications and APOE Ε4 Allele. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 935–944.

- Kivipelto, M.; Helkala, E.L.; Laakso, M.P.; Hänninen, T.; Hallikainen, M.; Alhainen, K.; Iivonen, S.; Mannermaa, A.; Tuomilehto, J.; Nissinen, A.; et al. Apolipoprotein E Epsilon4 Allele, Elevated Midlife Total Cholesterol Level, and High Midlife Systolic Blood Pressure Are Independent Risk Factors for Late-Life Alzheimer Disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 149–155.

- Huang, C.C.; Chung, C.M.; Leu, H.B.; Lin, L.Y.; Chiu, C.C.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chiang, C.H.; Huang, P.H.; Chen, T.J.; Lin, S.J.; et al. Diabetes Mellitus and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87095.

- Profenno, L.A.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Faraone, S.V. Meta-Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease Risk with Obesity, Diabetes, and Related Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 505–512.

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Wilson, R.S.; Bienias, J.L.; Evans, D.A.; Bennett, D.A. Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Alzheimer Disease and Decline in Cognitive Function. Arch. Neurol. 2004, 61, 661–666.

- Hassing, L.B.; Dahl, A.K.; Thorvaldsson, V.; Berg, S.; Gatz, M.; Pedersen, N.L.; Johansson, B. Overweight in Midlife and Risk of Dementia: A 40-Year Follow-Up Study. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 893–898.

- Razay, G.; Vreugdenhil, A. Obesity in Middle Age and Future Risk of Dementia: Midlife Obesity Increases Risk of Future Dementia. BMJ 2005, 331, 455.

- Kivipelto, M.; Ngandu, T.; Fratiglioni, L.; Viitanen, M.; Kåreholt, I.; Winblad, B.; Helkala, E.L.; Tuomilehto, J.; Soininen, H.; Nissinen, A. Obesity and Vascular Risk Factors at Midlife and the Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 1556–1560.

- Hamer, M.; Chida, Y. Physical activity and risk of neurodegenerative disease: A systematic review of prospective evidence. Psychol. Med. 2008, 39, 3–11.

- Beckett, M.W.; Ardern, C.I.; Rotondi, M.A. A meta-analysis of prospective studies on the role of physical activity and the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 9.

- Stern, Y.; Gurland, B.; Tatemichi, T.K.; Tang, M.X.; Wilder, D.; Mayeux, R. Influence of Education and Occupation on the Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease. JAMA. 1994, 271, 1004–1010.

- Samadi, M.; Moradi, S.; Moradinazar, M.; Mostafai, R.; Pasdar, Y. Dietary pattern in relation to the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 2031–2043.

- Pistollato, F.; Iglesias, R.C.; Ruiz, R.; Aparicio, S.; Crespo, J.; Lopez, L.D.; Manna, P.P.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Nutritional Patterns Associated with the Maintenance of Neurocognitive Functions and the Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Human Studies. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 131, 32–43.

- Van Den Brink, A.C.; Brouwer-Brolsma, E.M.; Berendsen, A.A.M.; Van De Rest, O. The Mediterranean, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diets Are Associated with Less Cognitive Decline and a Lower Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease—A Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 1040–1065.

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND Diet Slows Cognitive Decline with Aging. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 1015–1022.

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND Diet Associated with Reduced Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014.

- WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Plant-Based Diets and Their Impact on Health, Sustainability and the Environment: A Review of the Evidence; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; pp. 1–11.

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980.

- Richter, M.; Boeing, H.; Grünewald-Funk, D.; Heseker, H.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Oberritter, H.; Strohm, D.; Watzl, B. Vegan Diet. Position of the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Ernaehrungs Umsch. Int. 2016, 63, 92–102.

- Pye, A.; Bash, K.; Joiner, A.; Beenstock, J. Good for the Planet and Good for Our Health: The Evidence for Whole-Food Plant-Based Diets. BJPsych Int. 2022, 19, 90–92.

- Miki, A.J.; Livingston, K.A.; Karlsen, M.C.; Folta, S.C.; McKeown, N.M. Using Evidence Mapping to Examine Motivations for Following Plant-Based Diets. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa013.

- Termannsen, A.D.; Clemmensen, K.K.B.; Thomsen, J.M.; Nørgaard, O.; Díaz, L.J.; Torekov, S.S.; Quist, J.S.; Færch, K. Effects of Vegan Diets on Cardiometabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13462.

- Selinger, E.; Neuenschwander, M.; Koller, A.; Gojda, J.; Kühn, T.; Schwingshackl, L.; Barbaresko, J.; Schlesinger, S. Evidence of a Vegan Diet for Health Benefits and Risks—An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Observational and Clinical Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022.

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Shi, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, Y. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Cognitive Disorders in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 871061.

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. Fruit, Vegetables and Prevention of Cognitive Decline or Dementia: A Systematic Review of Cohort Studies. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 626–630.

- Jiang, X.; Huang, J.; Song, D.; Deng, R.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Z. Increased Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables Is Related to a Reduced Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 18.

- Fieldhouse, J.L.P.; Doorduijn, A.S.; de Leeuw, F.A.; Verhaar, B.J.H.; Koene, T.; Wesselman, L.M.P.; de van der Schueren, M.; Visser, M.; van de Rest, O.; Scheltens, P.; et al. A Suboptimal Diet Is Associated with Poorer Cognition: The NUDAD Project. Nutrients 2020, 12, 703.

- Collins, A.E.; Saleh, T.M.; Kalisch, B.E. Naturally Occurring Antioxidant Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 213.

- Heneka, M.T.; Golenbock, D.T.; Latz, E. Innate Immunity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 229–236.

- Su, C.; Zhao, K.; Xia, H.; Xu, Y. Peripheral Inflammatory Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 300–309.

- Passamonti, L.; Tsvetanov, K.A.; Jones, P.S.; Bevan-Jones, W.R.; Arnold, R.; Borchert, R.J.; Mak, E.; Su, L.; O’Brien, J.T.; Rowe, J.B. Neuroinflammation and Functional Connectivity in Alzheimer’s Disease: Interactive Influences on Cognitive Performance. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 7218–7226.

- Barbaresko, J.; Koch, M.; Schulze, M.B.; Nöthlings, U. Dietary Pattern Analysis and Biomarkers of Low-Grade Inflammation: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 511–527.

- Menzel, J.; Biemann, R.; Longree, A.; Isermann, B.; Mai, K.; Schulze, M.B.; Abraham, K.; Weikert, C. Associations of a Vegan Diet with Inflammatory Biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1933.

- Šebeková, K.; Krajčovičová-Kudláčková, M.; Schinzel, R.; Faist, V.; Klvanová, J.; Heidland, A. Plasma Levels of Advanced Glycation End Products in Healthy, Long-Term Vegetarians and Subjects on a Western Mixed Diet. Eur. J. Nutr. 2001, 40, 275–281.

- Franco-De-Moraes, A.C.; De Almeida-Pititto, B.; Da Rocha Fernandes, G.; Gomes, E.P.; Da Costa Pereira, A.; Ferreira, S.R.G. Worse Inflammatory Profile in Omnivores than in Vegetarians Associates with the Gut Microbiota Composition. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2017, 9, 62.

- Sutliffe, J.T.; Wilson, L.D.; de Heer, H.D.; Foster, R.L.; Carnot, M.J. C-Reactive Protein Response to a Vegan Lifestyle Intervention. Complement. Ther. Med. 2015, 23, 32–37.

- Visser, M.; Bouter, L.M.; McQuillan, G.M.; Wener, M.H.; Harris, T.B. Elevated C-Reactive Protein Levels in Overweight and Obese Adults. JAMA 1999, 282, 2131–2135.

- Menzel, J.; Jabakhanji, A.; Biemann, R.; Mai, K.; Abraham, K.; Weikert, C. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Associations of Vegan and Vegetarian Diets with Inflammatory Biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21736.

- Chen, H.; Du, Y.; Liu, S.; Ge, B.; Ji, Y.; Huang, G. Association between Serum Cholesterol Levels and Alzheimer’s Disease in China: A Case-Control Study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 405–411.

- Marcum, Z.A.; Walker, R.; Bobb, J.F.; Sin, M.K.; Gray, S.L.; Bowen, J.D.; McCormick, W.; McCurry, S.M.; Crane, P.K.; Larson, E.B. Serum Cholesterol and Incident Alzheimer’s Disease: Findings from the Adult Changes in Thought Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 2344–2352.

- Rantanen, K.K.; Strandberg, A.Y.; Pitkälä, K.; Tilvis, R.; Salomaa, V.; Strandberg, T.E. Cholesterol in Midlife Increases the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease during an up to 43-Year Follow-Up. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 5, 390–393.

- Helzner, E.P.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Scarmeas, N.; Cosentino, S.; Brickman, A.M.; Glymour, M.M.; Stern, Y. Contribution of Vascular Risk Factors to the Progression in Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 343–348.

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, Vegan Diets and Multiple Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649.

- Appleby, P.N.; Davey, G.K.; Key, T.J. Hypertension and Blood Pressure among Meat Eaters, Fish Eaters, Vegetarians and Vegans in EPIC–Oxford. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 645–654.

- Pollakova, D.; Andreadi, A.; Pacifici, F.; Della-Morte, D.; Lauro, D.; Tubili, C. The Impact of Vegan Diet in the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2123.

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Halloran, A.; Rippin, H.L.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Dardavesis, T.I.; Williams, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Chourdakis, M. Intake and Adequacy of the Vegan Diet. A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3503–3521.

- Elorinne, A.L.; Alfthan, G.; Erlund, I.; Kivimäki, H.; Paju, A.; Salminen, I.; Turpeinen, U.; Voutilainen, S.; Laakso, J. Food and Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Finnish Vegans and Non-Vegetarians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148235.

- Kim, Y.A.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Polyphenols and Glycemic Control. Nutrients 2016, 8, 17.

- Ylönen, K.; Saloranta, C.; Kronberg-Kippilä, C.; Groop, L.; Aro, A.; Virtanen, S.M. Associations of Dietary Fiber with Glucose Metabolism in Nondiabetic Relatives of Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes: The Botnia Dietary Study. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 1979–1985.

- Kahleova, H.; Petersen, K.F.; Shulman, G.I.; Alwarith, J.; Rembert, E.; Tura, A.; Hill, M.; Holubkov, R.; Barnard, N.D. Effect of a Low-Fat Vegan Diet on Body Weight, Insulin Sensitivity, Postprandial Metabolism, and Intramyocellular and Hepatocellular Lipid Levels in Overweight Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2025454.

- Bairamian, D.; Sha, S.; Rolhion, N.; Sokol, H.; Dorothée, G.; Lemere, C.A.; Krantic, S. Microbiota in Neuroinflammation and Synaptic Dysfunction: A Focus on Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 19.

- Lazar, E.; Sherzai, A.; Adeghate, J.; Sherzai, D. Gut Dysbiosis, Insulin Resistance and Alzheimer’s Disease: Review of a Novel Approach to Neurodegeneration. Front. Biosci. (Schol. Ed.) 2021, 13, 17–29.

- Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.L. Gut Microbiota and Dysbiosis in Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Pathogenesis and Treatment. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 5026–5043.

- Vogt, N.M.; Kerby, R.L.; Dill-McFarland, K.A.; Harding, S.J.; Merluzzi, A.P.; Johnson, S.C.; Carlsson, C.M.; Asthana, S.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; et al. Gut Microbiome Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13537.

- Angelucci, F.; Cechova, K.; Amlerova, J.; Hort, J. Antibiotics, Gut Microbiota, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 108.

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet Rapidly and Reproducibly Alters the Human Gut Microbiome. Nature 2013, 505, 559–563.

- Dawczynski, C.; Weidauer, T.; Richert, C.; Schlattmann, P.; Dawczynski, K.; Kiehntopf, M. Nutrient Intake and Nutrition Status in Vegetarians and Vegans in Comparison to Omnivores—The Nutritional Evaluation (NuEva) Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 819106.

- Wong, M.W.; Yi, C.H.; Liu, T.T.; Lei, W.Y.; Hung, J.S.; Lin, C.L.; Lin, S.Z.; Chen, C.L. Impact of Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota: An Update on the Clinical Implications. Tzu-Chi Med. J. 2018, 30, 200–203.

- Tomova, A.; Bukovsky, I.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Alwarith, J.; Barnard, N.D.; Kahleova, H. The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 47.

- Kohnert, E.; Kreutz, C.; Binder, N.; Hannibal, L.; Gorkiewicz, G.; Müller, A.; Storz, M.A.; Huber, R.; Lederer, A.K. Changes in Gut Microbiota after a Four-Week Intervention with Vegan vs. Meat-Rich Diets in Healthy Participants: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 727.

- D’Argenio, V.; Veneruso, I.; Gong, C.; Cecarini, V.; Bonfili, L.; Eleuteri, A.M. Gut Microbiome and Mycobiome Alterations in an In Vivo Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Genes 2022, 13, 1564.

- Ling, Z.; Zhu, M.; Yan, X.; Cheng, Y.; Shao, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, R.; Wu, S. Structural and Functional Dysbiosis of Fecal Microbiota in Chinese Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 634069.

- Prochazkova, M.; Budinska, E.; Kuzma, M.; Pelantova, H.; Hradecky, J.; Heczkova, M.; Daskova, N.; Bratova, M.; Modos, I.; Videnska, P.; et al. Vegan Diet Is Associated With Favorable Effects on the Metabolic Performance of Intestinal Microbiota: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Omics Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 783302.

- Losno, E.A.; Sieferle, K.; Armando Perez-Cueto, F.J.; Ritz, C.; Losno, C.; Sieferle, E.A.; Perez-Cueto, K.; Ritz, F.J.A. Vegan Diet and the Gut Microbiota Composition in Healthy Adults. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2402.

- Qian, X.H.; Xie, R.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Chen, S.D.; Tang, H.D. Mechanisms of Short-Chain Fatty Acids Derived from Gut Microbiota in Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1252.

- Wu, L.; Han, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Peng, G.; Liu, P.; Yue, S.; Zhu, S.; Chen, J.; Lv, H.; Shao, L.; et al. Altered Gut Microbial Metabolites in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Signals in Host–Microbe Interplay. Nutrients 2021, 13, 228.

- Trefflich, I.; Dietrich, S.; Braune, A.; Abraham, K.; Weikert, C. Short-and Branched-Chain Fatty Acids as Fecal Markers for Microbiota Activity in Vegans and Omnivores. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1808.

- Wu, G.D.; Compher, C.; Chen, E.Z.; Smith, S.A.; Shah, R.D.; Bittinger, K.; Chehoud, C.; Albenberg, L.G.; Nessel, L.; Gilroy, E.; et al. Comparative Metabolomics in Vegans and Omnivores Reveal Constraints on Diet-Dependent Gut Microbiota Metabolite Production. Gut 2016, 65, 63–72.

- Reiss, A.; Jacobi, M.; Rusch, K.; Andreas, S. Association of Dietary Type with Fecal Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids in Vegans and Omnivores. J. Int. Soc. Microbiota 2016, 1, 1–19.

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; et al. High-Level Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Beneficially Impacts the Gut Microbiota and Associated Metabolome. Gut 2016, 65, 1812–1821.

- Cattaneo, A.; Cattane, N.; Galluzzi, S.; Provasi, S.; Lopizzo, N.; Festari, C.; Ferrari, C.; Guerra, U.P.; Paghera, B.; Muscio, C.; et al. Association of Brain Amyloidosis with Pro-Inflammatory Gut Bacterial Taxa and Peripheral Inflammation Markers in Cognitively Impaired Elderly. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 49, 60–68.

- Gentile, C.L.; Weir, T.L. The Gut Microbiota at the Intersection of Diet and Human Health. Science 2018, 362, 776–780.

- Yang, D.S.; Yip, C.M.; Huang, T.H.J.; Chakrabartty, A.; Fraser, P.E. Manipulating the amyloid-β aggregation pathway with chemical chaperones. JBC 1999, 274, 32970–32974.

- Vogt, N.M.; Romano, K.A.; Darst, B.F.; Engelman, C.D.; Johnson, S.C.; Carlsson, C.M.; Asthana, S.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Bendlin, B.B.; et al. The Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide Is Elevated in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2018, 10, 124.

- Arrona Cardoza, P.; Spillane, M.B.; Morales Marroquin, E. Alzheimer’s disease and gut microbiota: Does trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) play a role? Nutr. Rev. 2022, 8, 271–281.

- Zarbock, K.R.; Han, J.H.; Singh, A.P.; Thomas, S.P.; Bendlin, B.B.; Denu, J.M.; Yu, J.-P.J.; Rey, F.E.; Ulland, T.K. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Reduces Neurite Density and Plaque Intensity in a Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 90, 585–597.

- Li, D.; Ke, Y.; Zhan, R.; Liu, C.; Zhao, M.; Zeng, A.; Shi, X.; Ji, L.; Cheng, S.; Pan, B.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes brain aging and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell. 2018, 17, e12768.

- Gao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X. Decreased levels of circulating trimethylamine N-oxide alleviate cognitive and pathological deterioration in transgenic mice: A potential therapeutic approach for Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2019, 11, 8642–8663.

- Lombardo, M.; Aulisa, G.; Marcon, D.; Rizzo, G. The Influence of Animal- or Plant-Based Diets on Blood and Urine Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) Levels in Humans. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 56–68.

- Argyridou, S.; Davies, M.J.; Biddle, G.J.H.; Bernieh, D.; Suzuki, T.; Dawkins, N.P.; Rowlands, A.V.; Khunti, K.; Smith, A.C.; Yates, T. Evaluation of an 8-Week Vegan Diet on Plasma Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Postchallenge Glucose in Adults with Dysglycemia or Obesity. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1844–1853.

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of l-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585.

- Obeid, R.; Awwad, H.M.; Keller, M.; Geisel, J. Trimethylamine-N-oxide and its biological variations in vegetarians. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2599–2609.

- Jain, R.; Larsuphrom, P.; Degremont, A.; Latunde-Dada, G.O.; Philippou, E. Association between Vegetarian and Vegan Diets and Depression: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Bull. 2022, 47, 27–49.

- Iguacel, I.; Huybrechts, I.; Moreno, L.A.; Michels, N. Vegetarianism and Veganism Compared with Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 361–381.

- Link, L.B.; Hussaini, N.S.; Jacobson, J.S. Change in Quality of Life and Immune Markers after a Stay at a Raw Vegan Institute: A Pilot Study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2008, 16, 124–130.

- Sultana, B.; Anwar, F. Flavonols (kaempeferol, quercetin, myricetin) contents of selected fruits, vegetables and medicinal plants. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 879–884.

- Grewal, A.K.; Singh, T.G.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, V.; Singh, M.; Rahman, M.H.; Najda, A.; Walasek-Janusz, M.; Kamel, M.; Albadrani, G.M. Mechanistic Insights and Perspectives Involved in Neuroprotective Action of Quercetin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111729.

- Dixon Clarke, S.E.; Ramsay, R.R. Dietary Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase A. J. Neural Transm. 2011, 118, 1031–1041.

- Zhang, X.W.; Chen, J.Y.; Ouyang, D.; Lu, J.H. Quercetin in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of preclinical studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 493.

- Paula, P.C.; Maria, S.G.A.; Luis, C.H.; Patricia, C.G.G. Preventive effect of quercetin in a triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice model. Molecules 2019, 24, 2287.

- Mehta, V.; Parashar, A.; Udayabanu, M. Quercetin prevents chronic unpredictable stress induced behavioral dysfunction in mice by alleviating hippocampal oxidative and inflammatory stress. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 171, 69–78.

- Ke, F.; Li, H.R.; Chen, X.X.; Gao, X.R.; Huang, L.L.; Du, A.Q.; Jiang, C.; Li, H.; Ge, J.F. Quercetin alleviates LPS-induced depression-like behavior in rats via regulating BDNF-related imbalance of copine 6 and TREM1/2 in the hippocampus and PFC. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 10, 544.

- Taber, L.; Chiu, C.H.; Whelan, J. Assessment of the arachidonic acid content in foods commonly consumed in the American diet. Lipids 1998, 33, 1151–1157.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!