Lupinus albus L. (lupine) is a legume whose grain/seed has gained increasing interest. Its recognized nutritional properties, namely a high content of protein, dietary fiber and its low fat content, make lupine a suitable alternative not only for animal protein, but also as a substitute for more processed and less balanced flours from a nutritional point of view, used in the preparation of bread, cakes and cookies, among others. In addition, its nutritional and bioactive compounds have potential benefits for human health in the prevention and treatment of some diseases. However, the existence of some anti-nutritional compounds and contaminants reveal some concern, requiring effective methods for their detection and eventual removal.

1. Introduction

In recent times, there has been a growing interest in plant-derived nutrients and bioactive compounds, not only due to economic and environmental factors but also due to the need to develop new, safe and healthy foods that can respond to the growing awareness and interest in healthy eating habits

[1].

In this sense, the interest for sweet lupine seeds is continuously growing, stimulated by its flexibility in food preparation as well as by the increasing knowledge of the health benefits they provide

[2]. Among the species of the genus Lupinus, the white lupinus,

Lupinus albus L., has notable potential. The production of this genus of legume is increasingly recurrent, not only because of the possibility of cultivation in poor soils and under adverse conditions, but also due to its use in animal nutrition (feed or protein supplementation for ruminants) and by humans, because seeds (the most commonly used part of lupin) have high protein and oil content. On the other hand, soil fertility can be improved by supplementing poor soils with nitrogen compounds

[3][4].

One of the reasons for the increased interest in this legume is the numerous studies that show that it provides positive health benefits, particularly in the area of dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia and hypertension prevention

[2]. These benefits are related to their content in bioactive compounds, with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties

[5].

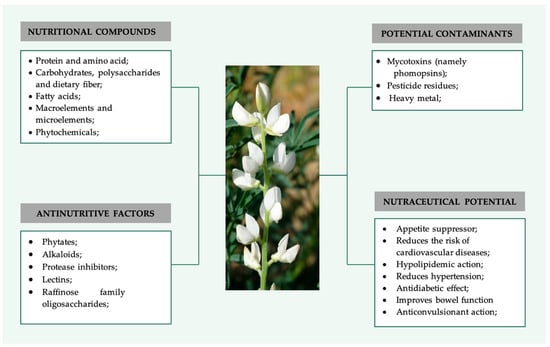

Lupine was chosen for this research as it (i) is a good break crop because it has the ability to fix nitrogen, (ii) it adapts well to different environmental conditions, which is an important feature due to climatic changes, and due to (iii) its high content of protein and bioactive compounds with valuable biological properties. This appraisal research intends to compile the most valuable information regarding Lupinus albus seeds, namely its nutritional and anti-nutritional components. Moreover, it also addresses the possible contaminants of lupine seeds, focusing on mycotoxins. Finally, the potential health benefits of lupine seeds are discussed based on the scientific evidence of clinical trials and studies carried out with animal models (Figure 1). The by-products of L. albus are not addressed in this research.

Figure 1. Summary of the main components of L. albus including nutrients, bioactive and antinutritive factors and potential contaminants, as well as main nutraceutical potential of this legume. (Photo of the species from the Botanical Garden UTAD, Digital Flora of Portugal).

2. Lupin (Lupinus albus L.)

2.1. General Description

White lupin, the common name for

Lupinus albus L., is a species of the genus Lupinus, tribe Genisteae, family Leguminosae or Fabaceae. This type of Lupin is a non-native cultivated, annual legume that can reach a height of approximately 120 cm. It also has a strong stem, which in combination with the secondary roots, can penetrate the soil to a depth of 1.5 m

[6]. Leaves are alternate (which means that each node has only one leaf) and with five to nine leaflets, nearly smooth above and hairy beneath. Individual plants produce several orders of inflorescences and branches, resulting in clusters of long, oblong pods, each cluster having three to seven pods, and each pod containing three to seven seeds

[7].

Like most of the members of their family, white lupins can fix the nitrogen provided by the atmosphere into ammonia. This allows the fertilization of the soil for other plants and allows lupins to be tolerant to infertile, acidic and sandy soils and able to improve the quality of poor soils

[8].

White lupine flowers in May–June. The flowers are white to violet, with the upper lip being entirely three-toothed and the lower lip being entirely or slightly three-toothed. The seeds are large, cream in color with a circular flattened shape, and with a 1000-seed-weight of 350–400 g

[8].

Furthermore, white lupin is primarily a cross-pollinated crop, but self-pollination of 50–85% has been reported

[7]. Due to this biological floral characteristic, sweet Lupine is selected for the production of pure lines

[9]. Bitter and sweet forms of white lupin exist, but the bitter forms have a high alkaloid content, and for this reason, the sweet form is preferable to be cultivated and consumed

[6]. However, although sweet lupine is more advantageous for the food industry, bitter lupine can fix more nitrogen, providing an alternate use of inorganic N fertilizers. In a study conducted by Staples et al., it was observed that white lupine lines with higher seed alkaloid concentrations (bitter lines) had higher root nodulation for symbiotic N fixation. Furthermore, in this same study, by characterizing the concentration of alkaloids in leaves, pod shells and seeds of white lupine (

L. albus), it was possible to perceive that some strains had different alkaloids in seeds, leaves and pod shells. This indicates that it may be possible to develop lupine strains with sweet or bitter seeds, each individually combined with different alkaloid contents in the leaves or pods. The significance of these results is that it may be possible to develop strains of lupine that have sweet seeds for use as food or feed, while the remaining plant tissue contains high levels of alkaloids to make it suitable for helping to control insect pests or destructive microorganisms

[10].

2.2. Use of the Plant over Times

The white lupin is a species mainly distributed around the Mediterranean and along the Nile valley. In these areas, it has been traditionally cultivated for several thousand years

[9].

Lupins can be used for many purposes. These include food, pasture improvement, ornamentation, erosion control and soil stabilization. Furthermore, the bitter species can be used to control some pests due to its alkaloid content

[11].

Historically, Egyptians, Romans and Greeks have used lupine as a soil fertilizer since this plant has the ability to grow in poor, acidic, sandy soils and in adverse weather conditions. In pre-Columbian times (before the arrival of Europeans in America), lupine was used as a food source for these populations; it was soaked and then cooked to remove the bitter taste derived from the presence of alkaloids (quinolizidine alkaloids) in the lupine

[12].

In the modern age (15th to 18th centuries),

L. albus was introduced in Germany. The results of introducing this plant as a food source were poorer than expected, but the cultivation of lupines in the sandy coastal plains of the Baltic prospered. It was used predominantly as animal feed and as soil enrichment due to its nitrogen fixing properties. However, until the First World War, the emergence of toxicity associated with lupine in sheep led to a decrease in interest in its cultivation

[12].

During and after the first war period in Germany, due to the food shortage, the attention given to lupine was redoubled as it constitutes an alternative source of protein. With increasing interest in lupine, research on reducing the alkaloid content of lupine caught the attention of some scientists at the Kaiser Wilhelm Research Institute, who managed to reduce the alkaloid content from the traditional 1–3% to less than 0.02%

[12].

In addition to the important uses of lupine both in food and in agriculture, lupine had a relevant role in the traditional medicine of several civilizations. For example, it was used as one of the many traditional remedies of the civilizations of Jordan and Greece for the treatment of diabetes. Furthermore, its use was also reported for conditions such as abscesses, parasites, heart disease and rheumatism

[13].

A role in epilepsy has also been proposed

[13]. In the Middle Ages, a decoction was used to treat seizures, a condition that was associated with devil possession and wolves. Several studies have been carried out to understand the evidence of this use and the truth underneath. Studies were carried out in rats, where three extracts rich in lupine alkaloids (sparteine, cytisine, lupinine) were administered. It was noticed that these three alkaloids produced a non-specific depressant response of the central nervous system (CNS) in rats, especially at higher doses

[14]. In Pereira et al.

[15], the most relevant studies addressing the role of lupine alkaloids in CNS is addressed.

The interest in the production of

Lupinus albus has been growing recently due to its potential as a source of protein, its potential pharmaceutical purposes, the fact that it can be grown in a wide range of climatic conditions and due to the high content of alkaloids that, despite being toxic, when well isolated and formulated, can have beneficial effects on health, and can work as a natural pesticide for the plant itself

[16]. Furthermore, its adaptation to poor soils makes lupine an economically viable plant

[17]. Lupine is commonly consumed as a snack in the Middle East and is being used as a high-protein soy substitute in other parts of the world. For example, in Europe, lupine seeds have been used for many years to replace cereal grains in flours and pasta or are sometimes used as complete or partial substitutes for soybeans in the production of liquid or powdered vegetable drinks and tofu

[18].

However, although it is well known, widely cultivated and consumed by people living in Europe, its cultivation lags behind other legumes

[18]. However, from the year 2000 (88.091 t/y) to the year 2020 (457.963 t/y), a high growth in lupinus production in Europe was visible, which demonstrates the growing interest in lupines as food and feed. According to FAOSTAT, in 2020, the main lupine-producing countries in Europe were Poland (261.500 t/y), Germany (34.100 t/y), France (12.820 t/y) and Spain (2470.00 t/y)

[19].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules27238557