Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

The mulberry tree belongs to the Morus genus of the Moraceae family, and is distributed all over the world. The mulberry tree contains 24 species and one subspecies.

- mulberry

- extracts

- animal production

- active compounds

1. Introduction

Population growth, urbanization, and rising incomes have led to the dramatic demand for animal products [1]. The global demand for animal products will rise by more than two-thirds by the year 2050 [2]. With the increasing demand for animal products, we have to explore new non-conventional feed resources to ensure the sustainability of animal production [3,4]. A variety of alternative feed resources exist for livestock, such as crop residues, the leaves of shrubs and trees, and weeds. However, these alternative feed resources have a lower digestibility, a lower content of protein and energy, and higher antinutritional factors, which limit their application [5,6].

The mulberry tree belongs to the Morus genus of the Moraceae family, and is distributed all over the world [7]. The mulberry tree contains 24 species and one subspecies. Among them, M. albus, M. atropurpurea, M. multicaulis, and M. bombycis are the dominant species [8]. The mulberry tree originated in China, Japan, and the Himalayan foothills. China possesses the most mulberry land with over 626,000 ha, followed by India with around 280,000 ha [9].

The mulberry tree is rich in bioactive compounds, including polysaccharides, phenols, flavonoids, and alkaloids, and has been reported to possess potent beneficial properties, including antioxidative, antidiabetic, and anti-cholesterol [10]. All parts of the mulberry tree, including the leaves, fruits, stems, and roots, are used for various purposes [11]. In addition, mulberry leaves are an excellent source of protein for livestock, with 14.0–34.2% protein content [12,13]. Extensive studies have demonstrated that mulberry leaves are a high quality protein source in the diets of animals, including pigs [14], hens [15], sheep [16], and cattle [17]. However, the effects of the mulberry tree and its extracts on animals are dependent on several factors, such as animal species, level of supplementation, the method for using the mulberry, and farm management. Individual studies cannot take into account all of these variables.

2. Nutrients Derived from the Mulberry Tree and Its Extracts

The mulberry tree, a member of the family Moraceae and genus Morus [18], is widely distributed throughout the world [19]. Morus alba (white mulberry), Morus nigra (black mulberry), and Morus rubra (red mulberry) are the most common species [20]. The mulberry tree is a potential protein source for animals. Different parts of the mulberry, especially the leaves and fruits, contain a variety of nutrients [21].

2.1. Leaves

The nutritional composition of the mulberry leaves is influenced by many factors, such as the varieties, environments, ecologies, and harvest conditions, and the nutritional composition varies greatly in different studies. All of the reported nutrient components in the mulberry leaves are displayed in Table 1. Fresh mulberry leaves contain dry matter (DM, 19.8–30.40%), a substantial amount of crude protein (CP, 4.72–22.3%), fats (0.64–4.36%), crude fiber (CF, 5.26–15.9%), total ash (4.10–14.50%), carbohydrates (carb, 8.01–13.42%), neutral detergent fiber (NDF, 8.15–43.4%), and gross energy (GE, 69–224 kcal/100 g) [22,23,24,25,26]. Moreover, according to Srivastava et al. [22], mulberry leaves are a plentiful source of important minerals and vitamins, such as calcium (Ca, 380–786 mg/100 g), ascorbic acid (200–280 mg/100 g), β-carotene (10,000–14,688 μg/100 g), iron (Fe, 4.7–10.36 mg/100 g), zinc (Zn, 0.22–1.12 mg/100 g), and tannic acid (0.04–0.08%).

As for dried mulberry leaves powder, it contains DM (18.0–95.5%), CP (11.75–37.36%), fats (2–11.10%), CF (5.4–32.3%), nitrogen free extract (NFE, 42.2–54%), NDF (19.38–36.66%), acid detergent fiber (ADF, 10.2–29.7%), total ash (7.56–22.36%), carb (9.7–56.42%), and GE (113–422 kcal/100 g) [22,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Dried mulberry leaves powder also possesses Ca (137.5–2226 mg/100 g), ascorbic acid (100–200 mg/100 g), β-carotene (8438–13,125 μg/100 g), Fe (14.15–35.72 mg/100 g), Zn (0.72–5.75 mg/100 g), and tannic acid (0.12–0.76%) [22,27,31,32,36].

Table 1. Chemical composition of mulberry leaves.

| Authors | Species | Source | Country | Season | DM, % | CP, % | Fat 1, % | CF, % | NFE, % | NDF, % | ADF, % | Ash, % | Carb, % | GE, kcal/100 g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yao et al., 2000 | Morus alba L. | Fresh | China | Spring and Autumn | 23.6–30.4 | 19.6–21.9 | - | - | - | 37.5–43.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Srivastava et al., 2006 | Morus alba L. | Fresh | India | Spring | 23.32–28.87 | 4.72–9.96 | 0.64–1.35 | - | - | 8.15–11.32 | - | 4.26–5.32 | 8.01–13.42 | 69–79 |

| Dried leaf powder | 92.76–94.89 | 15.31–30.91 | 2.09–4.93 | - | - | 27.6–36.66 | - | 14.59–17.24 | 9.7–29.64 | 113–224 | ||||

| Todaro et al., 2009 | Morus latifolia | Fresh | Italy | Summer | 25.98 | 21.05 | 4.36 | - | - | 22.88 | 19.72 | 13.31 | - | - |

| Adeduntan et al., 2009 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | Nigeria | - | 20.65–27.84 | 21.24–21.66 | 5.31–8.02 | 8.74–13.7 | - | - | - | 8.19–12.63 | 47.27–56.42 | - |

| Kandylis et al., 2009 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | Greece | - | 89.4 | 15.1 | 2 | 18.9 | 54 | - | - | 10 | - | - |

| Al-Kirshi et al., 2009 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | Malaysia | - | 89.3 | 29.8 | 11.1 | 32.3 | - | 22.8 | 22.8 | 11.8 | - | 422 |

| Vu et al., 2011 | Morus alba L. | Fresh | The Netherlands | - | 19.8 | 22.3 | 3.5 | 15.9 | - | 31.1 | 18.3 | 14.5 | - | - |

| Sahoo et al., 2011 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | India | - | 27.8 | 19.4 | 4.1 | - | - | 36.1 | 26.8 | 13.3 | - | - |

| Guven, 2012 | Morus nigra | Dried leaf powder | Turkey | Summer | 42.2 | 16.06 | - | - | - | 22.08 | 19.46 | 17.5 | - | - |

| Morus alba | 46.27 | 18.73 | - | - | - | 19.38 | 17.33 | 15.4 | - | - | ||||

| Morus rubra | 37.36 | 11.75 | - | - | - | 33.33 | 24.06 | 22.36 | - | - | ||||

| Morus alba pendula | 25.97 | 23.72 | - | - | - | 29.53 | 26.06 | 17.7 | - | - | ||||

| Wang et al., 2012 | Morus atropurpurea Roxb | Dried leaf powder | China | Summer | - | 25.17 | 2.85 | - | - | 27.88 | 16.49 | - | - | - |

| Morus alba L. | - | 25.9 | 4.21 | - | - | 26.25 | 17.07 | - | - | - | ||||

| Morus multicaulis Perr | - | 25.18 | 4.91 | - | - | 27.54 | 17.66 | - | - | - | ||||

| Iqbal et al., 2012 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | Pakistan | - | 94.7 | 18.41 | 6.57 | 10.11 | - | - | - | 8.91 | - | - |

| Morus nigra L. | 93.3 | 19.76 | 5.13 | 12.32 | - | - | - | 9.12 | - | - | ||||

| Morus rubra L. | 95.5 | 24.63 | 4.24 | 8.17 | - | - | - | 11.73 | - | - | ||||

| Flaczyk et al., 2013 | Morus alba L. | Aqueous extracts | Poland | - | 94.6 | 12.7 | 0.15 | - | - | - | - | 22.7 | - | - |

| Dolis et al., 2017 | M. multicaulis | Fresh | Romania | Summer | - | 6.2 | 1.04 | 5.26 | 12.77 | - | - | 4.1 | - | - |

| Dried leaf powder | - | 21.16 | 3.54 | 17.88 | 43.46 | - | - | 13.96 | - | - | ||||

| Yu et al., 2018 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | China | Summer | - | 29.02–37.36 | - | 13.01–16.61 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| M. multicaulis Perr. | - | 27.63–36.42 | - | 11.46–15.27 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| M.atropurpurea Roxb. | - | 28.29–34.19 | - | 12.41–15.50 | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Cai et al., 2019 | Morus alba L. | Dried leaf powder | China | - | 18–27 | 17–19.4 | - | - | - | 21.8–27.8 | 10.2–13 | 10.8–12.8 | - | - |

| Kang et al., 2020 | - | Dried leaf powder | China | Spring and Autumn | - | 24.8 | 5.4 | - | 42.2 | 33.6 | 25.8 | - | - | - |

| - | 20.9 | 7 | - | 47.2 | 26.6 | 18.1 | - | - | - | |||||

| - | 26.9 | 6.3 | - | 43.1 | 25.2 | 29.7 | - | - | - | |||||

| - | 22.4 | 7.9 | - | 44.3 | 31.8 | 29.7 | - | - | - | |||||

| Ouyang et al., 2019 | Morus alba var. multicaulis | Dried leaf powder | China | Spring | 89.54 | 20.3 | 8.15 | - | - | 34.3 | 16.28 | 7.56 | - | - |

Dry matter (DM); crude protein (CP); crude fiber (CF); nitrogen free extract (NFE), neutral detergent fiber (NDF); acid detergent fiber (ADF); carbohydrate (Carb); gross energy (GE). 1 Fat was divided into crude fat and ether extract, both of which were determined by the AOAC methods. The studies of Srivastava et al., 2006 [22], Adeduntan et al., 2009 [27], Iqbal et al., 2012 [33], Flaczyk et al., 2013 [34] and Kang et al., 2020 [37] were described as crude fat. In the rest of studies, they were described as ether extract.

2.2. Fruits

The mulberry fruit also contains CP, fats, minerals, and other components, and is a healthy food choice for consumers [39]. Similar to mulberry leaves, the nutritional and chemical composition of the mulberry fruit changes with the varieties, environments, climatic conditions, and soil conditions. The average contents of the trace element components in the mulberry fruits are shown in Table 2. DM can range from 9.45% to 28.50%, CP can vary from 0.51% to 12.98%, fat can vary from 0.34% to 7.21%, CF can vary from 0.57% to 14.0%, ash can vary from 0.46% to 4.79%, and carb can vary from 13.83% to 71.7% [20,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. A study by Imran et al. [41] showed that the GE in the mulberry fruit can range from 67.36 to 84.22 kcal/100 g.

Table 2. Trace element composition of the mulberry fruits (mg/100 g).

| Authors | Species | Source | Country | Season | Fe | Zn | Ca | Mg, | K | Na | Mn | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ercisli et al., 2007 | Morus alba L. | Fresh | Turkey | - | 4.2 | - | 152 | 106 | 1668 | - | - | - |

| Morus rubra | 4.2 | - | 132 | 106 | 922 | - | - | - | ||||

| Morus nigra | 4.2 | - | 132 | 115 | 834 | - | - | - | ||||

| Koca et al., 2008 | Morus latifolia | Fresh | Turkey | - | 2.85 | 0.52 | 88.9 | 19.4 | 210.75 | 11.89 | 0.35 | 0.31 |

| Akbulut et al., 2009 | Morus nigra | Freeze-dried | Turkey | - | 3.72 | 0.96 | 304.4 | 95.9 | 1086.0 | 11.5 | - | 0.41 |

| Morus rubra | 1.22 | 1.16 | 443.7 | 103.3 | 1526.9 | 21.8 | - | 0.65 | ||||

| Morus alba L. | 5.29 | 0.90 | 292.7 | 90.4 | 1310.2 | 21.5 | - | 0.68 | ||||

| Sheng et al., 2009 | - | Fresh | China | - | 1.17 | 0.14 | 38.89 | 12.21 | 234.65 | 16.1 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Imran et al., 2010 | Morus alba L. | Fresh | Pakistan | Spring | 73.0 | 50.20 | 576 | 240 | 1731 | 280 | - | - |

| Morus nigra | 77.6 | 59.20 | 470 | 240 | 1270 | 272 | - | - | ||||

| Morus laevigata (Large white fruit) |

48.6 | 53.40 | 440 | 360 | 1650 | 260 | - | - | ||||

| Morus laevigata (Large black fruit) |

63.6 | 50.80 | 576 | 240 | 1644 | 264 | - | - | ||||

| Altundag et al. 2011 | Morus alba L. | Dry | Turkey | - | 37.45 | 4.47 | - | - | - | - | 4.36 | 1.28 |

| Wet | 40.80 | 4.38 | - | - | - | - | 4.25 | 1.31 | ||||

| Microwave | 36.17 | 3.78 | - | - | - | - | 4.16 | 1.23 | ||||

| Sánchez-Salcedo et al., 2015 | Morus alba | Fresh | Italy | - | 2.82–4.67 | 1.49–1.96 | 190–370 | 120–190 | 1620–2130 | 10 | 1.23–1.94 | 0.45–0.64 |

| Morus nigra | 2.39–3.71 | 1.57–2.25 | 210–430 | 130–190 | 1480–2170 | 10 | 1.23–1.81 | 0.28–0.52 | ||||

| Jiang et al., 2015 | Morus alba L. | Fresh | China | Summer | 6.96 | 0.21 | 71 | 32.5 | 239 | 6.2 | 0.31 | 0.10 |

| M. alba var. tatarica L. | 11.40 | 0.32 | 124 | 55.8 | 350 | 6.5 | 0.70 | 0.13 | ||||

| Morus nigra | 11.90 | 0.10 | 113 | 36.9 | 297 | 5.9 | 0.40 | 0.10 | ||||

| Sun et al., 2018 | - | Fresh | China | Spring | 7.72–30.13 | 4.06–10.58 | 180.61–423.30 | 13.96–33.38 | 87.70–208.44 | - | - | 0.04–0.50 |

Iron (Fe); Zinc (Zn); calcium (Ca); magnesium (Mg); kalium (K); sodium (Na), manganese (Mn); copper (Cu).

Additionally, the mulberry fruit also contains Fe (1.17–77.6 mg/100 g), Zn (0.14–59.20 mg/100 g), Ca (38.89–576 mg/100 g), magnesium (Mg, 12.21–360 mg/100 g), kalium (K, 87.70–2170 mg/100 g), sodium (Na, 5.9–280 mg/100 g), manganese (Mn, 0.03–4.36 mg/100 g), and copper (Cu, 0.04–1.31%) [20,40,41,42,43,46,47,48,49]. Ascorbic acid ranges from 15.20 to 22.4 mg/100 g [20,41]

Collectively, the chemical composition of mulberry leaves and mulberry fruits varies greatly due to the different varieties, geographical environment, seasons, and other factors. The results suggest that we should pay attention to the regional and variety differences of the mulberry tree’s raw materials, when using mulberry tree products in feed production.

3. Bioactive Compounds in the Mulberry and Their Bioactivities

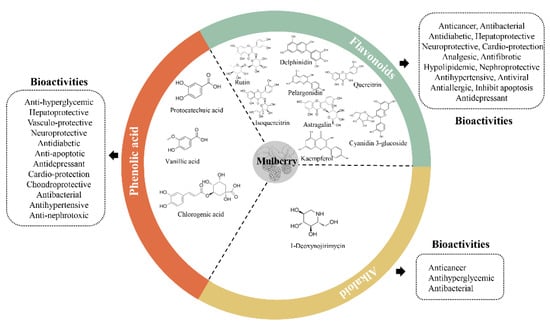

The history of the mulberry tree and its extracts used as a medicinal herb is very long, due to its extensive biological and pharmacological activities [50]. Mulberry plants contain a variety of compounds with medical and veterinary pharmacological properties, including alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and others. These compounds have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anticancer, antidiabetic, neuroprotective, cardioprotective, hepatoprotective, antihypertensive, anti-apoptosis, antiviral, anti-arteriosclerosis, and antidepressant properties (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Main mulberry components and their bioactivities.

The mulberry tree is identified as an appreciable source of flavonoids, which have beneficial effects on human and animal health. Previous studies reported that the concentrations of the total flavonoids were 9.84–58.42 mg/g in dried mulberry leaves from different varieties [33,35,51,52]. Flavonoids have been reported to exert diverse biological effects, such as anticancer, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, nephroprotective, antidiabetic, cardio-protection, and antibacterial, mainly associated with their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [53,54]. Further studies showed that the inflammatory and antioxidant effects of flavonoids were mediated through regulating the NF-κB, AP-1, PPAR, Nrf2, MAPKs, JNK, p38, ERK, PI3-K/Akt, and PKC signaling pathways [55,56].

1-Deoxynojirimycin (1-DNJ), a polyhydroxylated piperidine alkaloid [35], is a potent α-glucosidase inhibitor with unique bioactivities, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer [57,58,59]. 1-DNJ exhibited anti-hyperglycemic activity through regulating the expression of proteins related to glucose transport systems, glycolysis, and gluconeogenesis enzymes [60,61,62]. In addition, 1-DNJ also possesses anti-microbial properties. Hu et al. [61] reported that the 1-DNJ treatment could promote the growth of beneficial bacteria and suppress the growth of harmful bacteria in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model.

Phenolic acids were found to be excellent antioxidant agents. By scavenging free radicals, modulating the antioxidant enzyme activity, and regulating the signaling pathways associated with oxidative stress, the phenolic acids can exert an antioxidant activity [63,64]. Phenolic acids are also known for their anti-inflammatory properties. Oxidative stress and the resulting oxidative damage play an important role in the formation and progression of cancer [65]. To some extent, phenolic acids could inhibit the proliferation of colon cancer cells and induce apoptosis in cancer cells through oxidant-mediated mechanisms [66]. Previous studies demonstrated that phenolic acids could rupture the cell membrane integrity and inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria [67,68,69]. The significant antidiabetic effect of phenolic acids may be due to the reduced levels of oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines [70,71]. Peng et al. [72] found that phenolic acids maintain the glucose homeostasis by regulating the expression of the intestinal glucose transporters and proglucagon.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ani12243541

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!