Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

In a circular economy era the transition towards renewable and sustainable materials is very urgent. The development of bio-based solutions, that can ensure technological circularity in many priority areas (e.g., agriculture, biotechnology, ecology, green industry, etc.), is very strategic.

- plant biofactories

- genetic transformation

- chloroplast

- biomass hydrolysis

1. Enzymes for Lignocellulosic Waste Biorefinery

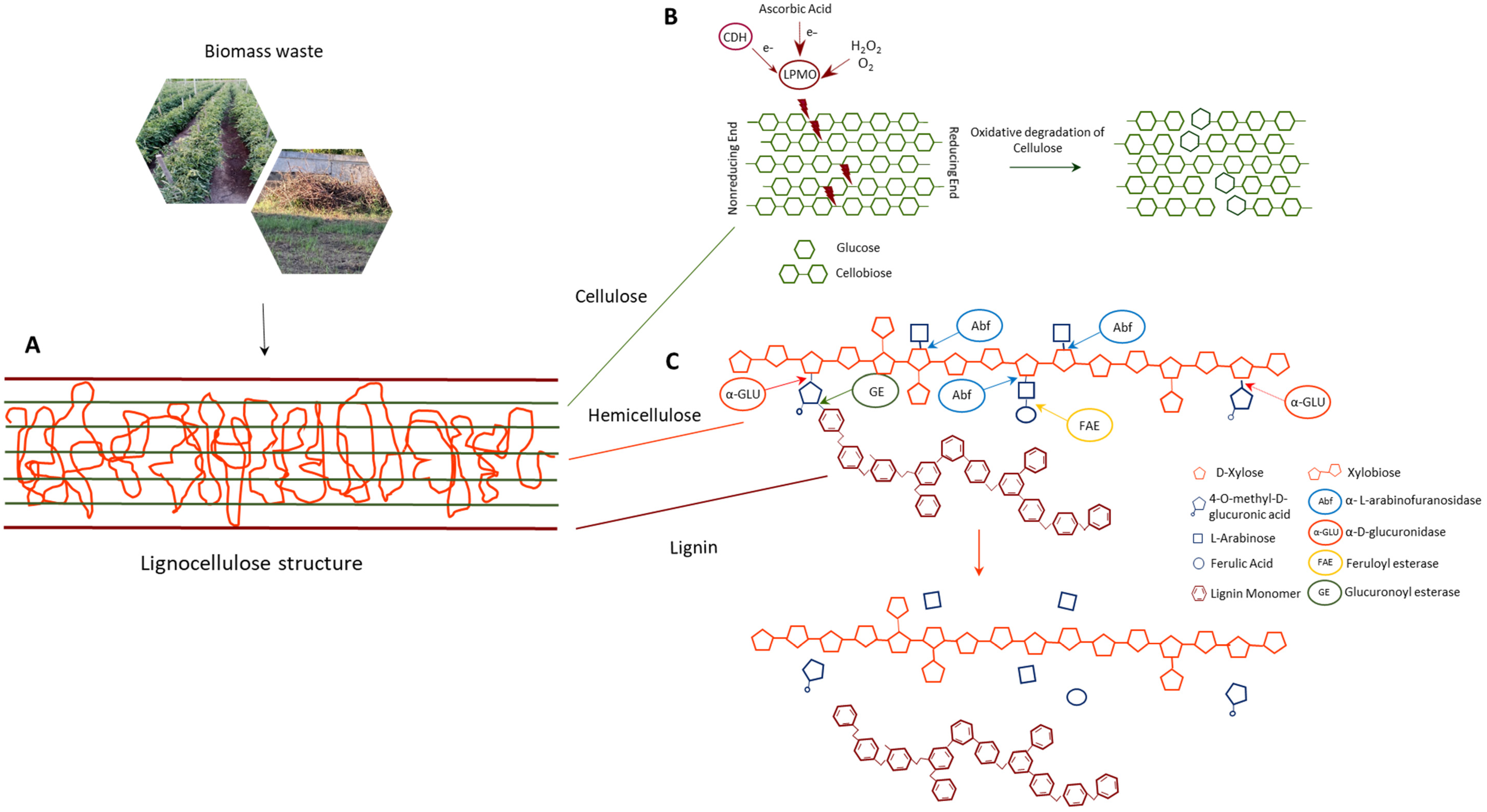

In the circular economy perspective, lignocellulose exploitation follows biorefinery concepts that involve the utilization of all the lignocellulosic biomass components. Only bio-based processes, realized by the application of enzymes instead of the classical methods, allow the lignocellulosic complexes to be disintegrated; this leads to polysaccharide bioconversion into simple sugars for the production of biofuels and chemicals, and the extraction of bioactive molecules with high biotechnological value [1]. The fundamental task of (hemi)cellulolytic enzymes, active on linear polysaccharides chains, is greatly improved by biocatalysts able to break down the chemical linkages (Figure 1) which strictly interconnect the different plant cell wall polymers. These enzymes, commonly named auxiliary enzymes, have a relevant role in substituting traditional chemical pretreatments, aiding in fermentable sugar recovery and allowing the extraction of powerful bioactive compounds, mainly of polyphenolic nature, that crosslink plant cell wall components [2]. Their biotechnological relevance makes their expression, through the transplastomic platform, of particular interest in a circular economy perspective. The possibility to obtain high protein yields, by plants as biofactories that utilize atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis, offers a cost-effective valuable alternative to the traditional reactor-based system with low environmental impact. Considering the cyanobacterial origin of chloroplasts, it is not surprising that enzymes from bacterial microorganisms fit well with plastid translation machinery. Therefore, reported in the following sections are the most promising auxiliary enzymes, never expressed in plants from bacterial and archaeal microorganisms, that could represent the new challenges of plastid transformation. Furthermore, the selected enzyme classes were expressed in bacterial hosts with high yields, without revealing particular toxicity profiles or problems in folding.

Figure 1. (A) Schematic structure of lignocellulosic biomass. (B) Action of LMPOs on crystalline cellulose chain by oxidative degradation. (C) Action of accessory enzymes on hemicellulose, with the cleavage of glycosidic and ester bonds between xylan and its side chains, and of ester bonds between hemicellulose and lignin.

1.1. Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases

Copper-dependent lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) are known as Auxiliary Activity (AA) families AA9-11 and AA13-16 in the Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZy) database [3], on account of their activity on polysaccharides. These boosting enzymes preferentially degrade polysaccharides characterized by high crystallinity, such as cellulose and chitin, but also hemicellulose, pectin, and starch [4]. LPMOs have recently assumed the role of key enzymes in the best-performing cellulolytic mixtures, and there are numerous studies aimed at identifying and optimizing these challenging biocatalysts.

LPMOs are distributed in most kingdoms of living organisms and are found in bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotes, including fungi, plants, and animals. Numerous studies have investigated fungal LPMOs, but bacterial LPMOs are still under exploration [3]. The first LPMO identified was the mono-copper oxidase from Serratia marcescens. The bacterium was capable to produce a chitin-active LPMO, formerly identified as Chitin Binding Protein (CBP) 21 [5], responsible for efficient chitin degradation [6]. The discovery of CBP21 was the key to identifying the novel family known as LPMOs.

Streptomycetes, soil microorganisms living on decaying lignocellulosic materials, are recognized as important LPMOs producers [7]. Among them, S. coelicolor A3 is the best-studied representative of this group, with seven LPMOs encoded by its genome [8] and heterologously expressed in E. coli.

Auxiliary activity 10A (TfAA10A) from T. fusca, a thermophilic soil bacterium with a good growth at 50 °C on cellulose, was cloned in E. coli [9]. Recently, this enzyme was also overexpressed in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus [10]. The first study on the expression and identification of a LPMO (NaLPMO10A) from Natrialbaceae archaeon [11], a halophilic alkalithermophilic archaeon, resulted in high interest. NaLPMO10A showed thermostability and pH stability under alkaline conditions (pH 9.0), and metal ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+) clearly enhanced the efficiency of chitin degradation.

The LPMOs ability to improve the hydrolysis efficiency of classical biocatalysts, on several lignocellulosic materials, implies an important possibility of reducing the enzymatic loads useful for the process of converting biomass into biofuel [4].

1.2. Arabinofuranosidases

Arabinofuranosidases (Abfs) remove L-arabinofuranosyl residues present on the side chains of xylan, with a high variation in terms of substrate preference and hydrolyzed linkages. Abfs are high value biotechnological tools in several industrial processes, including the synthesis of oligosaccharides [12], the hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass [13] and in the pulp and paper industry as an alternative to chemical chlorination [14]. Moreover, α-L-arabinofuranosidases are involved in the production of drug compounds [15] and improvement of some food properties, such as wine flavor and juice clarification [16]. In particular, Abfs specifically catalyze the hydrolysis of α-1,2, α-1,3, α-1,5 glycosidic bonds involving L-arabinofuranosyl residues [17]. In the CAZy database, the Abfs belong to the Glycosyl Hydrolase (GH) families 2, 3, 10, 43, 51, 54, and 62 [18]. Various arabinofuranosidases have been identified in several plants, fungi and bacteria, providing useful information for enzymatic characterization. In this context, the thermotolerant enzymes show a better stability and industrial applicability, and the thermophilic bacteria are major producers of the aforementioned biocatalysts [19].

Streptomycetes have been found to be the most abundant hemicellulases producer among actinomycetes. Streptomyces thermoviolaceus is able to produce a GH62 α-L-arabinofuranosidase (SthAbf62A) capable of withstanding high temperature (60 °C) and producing reducing sugars from polymeric arabinoxylan [20]. Recently, an Abf purified from Streptomyces lividus revealed interesting characteristics, resulting stable over a broad pH range of 3.0–11.0, and temperature of 30–80 °C, with an optimum temperature of 60 °C and pH 9.0 [21].

Two GH51 Abfs, Abf1Geo12 and Abf2Geo12 from the thermophilic bacterium Geobacillus stearothermophilus 12, showed relevant characteristics. Indeed, Abf1Geo12 and Abf2Geo12 resulted active in a broad range of pH (5.0–9.0) and temperatures of 50–85 °C and of 40–80 °C, respectively [22]. Comparable characteristics were found in Geobacillus vulcani GS90 α-L-arabinofuranosidase (GvAbf) that exhibits an optimum activity at 70 °C and pH 5.0 when expressed in E. coli [23]. Moreover, the studies conducted in fruit juice of apple, grape, peach and orange pulps, revealed that GvAbf and xylanase, working in synergy, implemented the reducing sugar level useful in fruit juice enrichment processes [22].

A performant hyperthermostable Abfs (Tt-Afs) gene from Thermotoga thermarum DSM5069, expressed in E. coli, showed an optimal activity at pH 5.0 and temperature of 95 °C [24].

The GH43 family has provoked particular interest and has many multifunctional xylanolytic enzymes, including bifunctional β-xylosidase/α-L-arabinofuranosidases. The bifunctional β-xylosidase/α-L-arabinosidase from the Archea Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 was expressed in E. coli [25]. The β-xylosidase retained 100% activity at 80 and 90 °C, while 100% activity of the Abfs was observed at 80 °C. A bifunctional GH43 α-L-arabinofuranosidase/β-xylosidase (CAX43) from Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus DSM8903 [26] displayed maximum activity at pH 6.0 and 70 °C. These enzymes are important for boosting xylo-oligosaccharide hydrolysis efficiency in biomass conversion, reducing production costs [27]. Additionally, the multifunctional enzymes are important, such as GH43 α-L-arabinofuranosidase/endoxylanase/β-D-xylosidase. In particular, Paenibacillus curdlanolyticus B-6 produced PcAxy43B, is capable of releasing arabinose, xylose, and XOSs from the arabinoxylan [18].

1.3. α-Glucuronidases

Glucuronic acid is a component of the structural polysaccharides that decorate the hetero-xylan polymer. D-glucuronic acid or its methyl derivative, 4-O-methyl-D-glucuronic acid bound to the C-2 positions of the D-xylose residues, are present in glucuronoxylans; when L-arabinofuranosyl moieties are also linked to xylan, the polymer takes the name of arabinoglucuronoxylans [28]. Glucuronic acid residues can form ester linkages to the hydroxyl groups of lignin, providing cross-links between the cell wall, and the lignin [28]. The strong bond with glucuronic acid can be hydrolyzed by α-glucuronidases, belonging to the families GH4, GH67 and GH115 of the CAZy database [29].

Despite the importance in nature of the glucuronic acid substituents, there are very few known α-glucuronidase encoding genes (<40), most of which are from fungi and bacteria [30]; while no archaeal α-glucoronidases have been identified so far.

Among the thermophilic bacteria, in Clostridium stercorarium and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharoliticum intracellular α-glucuronidase activities were found [31]. They showed a similar optimum pH (pH 5.5–6.5), but the C. stercorarium enzyme was more stable at 60 °C with a half-life of 14 h, almost 6-fold higher than T. saccharoliticum enzyme.

Two different strains of Geobacillus stearothermophilus, T6 and 236, produced α-glucuronidases belonging to the GH67 family, with optimal activity between 40 and 65 °C and pH 5.5–6.5 [32][33]. The biocatalyst of G. stearothermophilus 236 acts mainly on small substituted xylo-oligomers and is able to increase the yield of xylose from xylan, in combination with endoxylanase and β-xylosidase [32].

The hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima possess a gene encoding a thermoactive GH67 α-glucuronidase. This enzyme showed highest activity at 85 °C and pH 6.3, and produced xylobiose and 4-O-methylglucuronic acid [34]. The GH4 α-glucuronidase from T. maritima, active at 80 °C and pH 7.0, was also reported [35].

Glucuronoxylans represent a bottleneck in hemicellulose degradation. The use of α-glucuronidase, in synergy with other hemicellulolytic enzymes, facilitates the recovery of xylan. This process is also a crucial goal for biorefineries that rely on enzymatic degradation and the use of xylan in the production of biomaterials [36].

1.4. Feruloyl Esterases

Ferulic acid (FA) and other hydroxycynnamic acids (HCAs), which are esterified to the arabinose units of arabino-xylan and to arabinan and galactan, establish numerous inter-molecular connections among the polysaccharide chains and lignin. Feruloyl esterases (FAEs), cleaving most of these ester bonds, liberate FA and/or HCAs facilitating the release of fermentable sugars by glycosyl hydrolases [37][38]. For its recognized powerful antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, extensive studies address ferulic acid applications in several sectors such as food, medicine, pharma, water treatment, and cosmetic [39]. Further, FAEs-mediated transesterification reactions, that allow for improvement of FA solubility in water and lipophilic media by its transformation in feruloylated compounds, are of great biotechnological interest [40]. FAEs are classified as carbohydrate esterases and belong to a subclass of family CE1 of the CAZy database [28]. Although, still today, Fungi are considered as the most important producers of these enzymes, studies on FAEs from bacterial sources have already started since the nineties, discovering biocatalysts with relevant biotechnological properties. Important FAE producers are represented by Lactobacilli. Two FAEs from L. plantarum strains are considered good candidates for biotechnological applications due to their broad substrate specificity, one of them being able to work also on model substrates for tannases [41]. Six FAEs were described from L. fermentum JN248, some of which showed a good level of stability at high temperatures and pH, making these biocatalysts suitable for application in pulp and paper treatment. Moreover, the recovery of up to 70% of alkali extractable ferulic acids from de-starched wheat bran were obtained with the utilization of these FAEs in combination with a xylanase [42].

L. helveticus KCCM 11223 and L. acidofilus F46 also produce thermostable cinnamoyl esterases. The enzymes, optimally active at elevated temperatures (65 and 50 °C, respectively), were able to hydrolyze chlorogenic acid, releasing caffeic acid, with powerful antioxidant activity [43][44].

Geobacillus and Thermobacillus genera have also been studied as producers of thermophilic FAEs. The feruloyl esterase from G. thermoglucosidasius DSM 2542 (GthFAE), preferentially worked at pH 8.5 and 50–60 °C showing elevated stability at these conditions; thus, its main suggested application was in the pulp and paper sector [45]. Similarly, Tx-est1, the feruloyl esterase from Thermobacillus xylanilyticus, worked optimally at 65 °C and pH 8.5, retained 80% of its maximal activity at 80 °C and was stable at 50 °C for 24 h [46]. Thus, it was applied for the recovery of para-coumaric and diferulic acids from non-delignified wheat bran and straw, also in association with the xylanase from T. xylanolyticus, giving encouraging yields [46].

Feruloyl esterases also occur as multi-domain enzymes. High efficiencies in recalcitrant biomass degradation were verified for the two feruloyl esterases from Bacteriodetes ovatus and Flavobacterium johnsoniae, that present both acetyl esterase and FAE domains [47]. The other two bifunctional, multimodular FAEs were studied from Clostridium thermocellum that contained two xylanases’ domains (Xyn 10A and Xyn10B). The feruloyl esterase with a Xyn10A module recombinantly expressed in E. coli, revealed biotechnologically relevant features, being optimally active between pH 4.0 and 7.0 at 50–60 °C, and stable at 70 °C for 6 h [48][49].

1.5. Glucuronoyl Esterases

Glucuronoylesterases (GEs) are carbohydrate esterases that cleave ester bonds between 4-O-methyl-D-glucuronic acid (MeGlcA) residues of glucuronoxylan and lignin. These biocatalysts, cleaving the covalent bonds between polysaccharides and lignin, are the main contributors to plant cell wall recalcitrance against the enzymatic attack [50]. They reduce the costs for polysaccharide bioconversion into simple sugars, and support the routes of lignin exploitation [51]. Moreover, GEs actions in synergy with (hemi)cellulolytic hydrolases [52][53] lead to the recovery of glucuronidated xylo-oligosaccharides, known for their antibacterial and anti-inflammatory action. For their transesterification activity, GEs are also recognized as synthetic tools for the production of alkyl-branched glucuronic acid esters, and non-ionic surfactant with interesting properties for several applications [54].

GEs were assigned to the novel CAZy family CE15 [55] and, although the highest number of GEs has been studied from saprophitic Fungi, bacterial glucuronoyl esterases began to be investigated, revealing a broader substrate specificity than their fungal counterparts.

A wide substrate spectrum was revealed for MZ0003, a single-domain bacterial GE with optimal activity in the presence of 1M NaCl, which was identified from a metagenome library of arctic marine sediments [56]. MZ0003, overexpressed in E. coli, worked on model substrates for glucuronoyl and acetyl esterase activities. MZ0003 could find applications for the recovery of bioactive compounds from marine carbohydrate polymers. The GEs ability to work on a wide spectrum of substrates was often ascribed to the co-presence of multiple domains. CesA, a bimodular acetyl xylan esterase-glucuronoyl esterase, studied by Aurilia, et al. [57] as component of the cellulosome from Ruminococcus flavefaciens, revealed a C terminal domain whose GE function was subsequently demonstrated by Biely et al. [58] after its expression in E. coli. A multiple domain glucuronoyl esterase (CkXyn10C-GE15A), containing a module with xylanase activity and others with carbohydrate binding function, was studied from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor kristjansonii [59]. CkXyn10C-GE15 is the most thermostable GE studied so far, with an optimal temperature around 72 °C.

Several bacteria were able to produce multiple glucuronoyl esterases with complementary specificities. Three genes encoding for GEs were identified in the genome of the bacterium Teredinibacter turnerae, a symbiont of marine wood-boring bivalve ship-worms [60]. Only one of them was expressed in a soluble form in E. coli, worked optimally at pH 8.5, and was involved in the breakdown of lignin carbohydrate complexes of marine lignocellulosic biomass. Three bacteria, namely Opitutus terrae, Spirosoma linguale, and Solibacter usitatus, had genomes containing, respectively, four, three, and three ORFs encoding putative GEs [50], with higher activity than their fungal counterparts.

2. Other Enzymes for Waste Biorefinery

In advancing the circular economy, valorization of waste from the fishing industry, an untapped resource, which is cause of serious environmental concern, can be turned into a valuable opportunity. Processed seafood waste is mainly constituted by chitin (20–58% of dry weight), the most abundant biopolymer of oceans biomass [61], which represents the principal component of the exoskeleton of arthropods (crustaceans), and the endoskeleton of mollusks. In the biorefinery of chitin, a crystalline polysaccharide consisting of linear chains of β-1,4 linked N-acetyl glucosamine units, the fundamental role is played by chitinases and chitin deacetylases—an alternative to the traditional chemical procedure. In the following sections, several studies on the most biotechnologically relevant chitinases and chitin deacetylases are summarized.

2.1. Chitinases

Chitinases are glycosyl hydrolases included in families GH18, 19, and 20 of the CAZy database [62]. Chitinolytic enzymes are able to hydrolyze β-1,4-glucosidic linkages that connect N-acetyl glucosamine units of chitin chains. The biotechnological relevance of chitinases is widely recognized, mainly due to the beneficial properties of acetyl-glucosamine and chitooligosaccharides produced by their activity. These characteristics are at the basis of the numerous applications in medicine, food industry, biotechnology, agriculture, waste management, and crop protection sectors [63].

Several organisms express chitinases for different physiological functions, including fungi, bacteria, archaea, viruses, plants, insects, and crustaceans.

One of the first identified species involved in the degradation of chitin was S. marcescens. Able to produce [64] five different GH18 chitinolytic enzymes with maximum activity at 32 °C and pH of 8.0, S. marcescens is considered a model bacterium for the study of chitinolytic activities [65].

A thermophilic chitinase was produced by Paenibacillus sp. TKU052. The enzyme exhibited high catalytic activity at elevated temperature and acidic pH conditions (70 °C, pH 4.0–5.0), showing also a multi-functional behavior working as exochitinase, endochitinase, and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase [66].

Recently, it was highlighted that Chromobacterium violaceum possess a gene encoding a GH18 chitinase [67]. The chitinolytic enzyme (CvChi47) is a thermostable protein with an optimum hydrolytic capacity at 60 °C, retaining approximately 53.7% of its activity at 100 °C for 1 h.

Interestingly, even if there is less information on them, chitinases from Archaea have been exploited for their extreme characteristics. Recently, a chitinase with a dual hydrolytic activity on chitin and cellulose, from the hyperthermophilic anaerobe Thermococcus kodakarensis [68], showed thermal stability at 70–80 °C, retaining 40% of its maximum activity at 100 °C.

Two halophilic Archea, Halobacterium salinarum and Haloferax mediterranei, produce functionally active extracellular chitinases belonging to the GH18 family [69], with a high tolerance at elevated saline concentration.

A chitinase exhibiting high thermostability (95 °C) was found in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus chitonophagus, isolated from media containing chitin as the carbon source [70].

2.2. Chitin Deacetylase

Chitin deacetylases (CDAs) catalyze the N-deacetylation of insoluble chitin to chitosan; moreover, several deacetylases, named chitooligosaccharide deacetylase (CODs), are active on acetylated chitooligosaccharides (COS), and N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) [71]. Physico-chemical and biological properties of chitosan and COS are strictly dependent on their degree of polymerisation and fraction of acetylation; thus, the discovery of CDAs with novel specificities, and the definition of new CDA combinations have recently gained considerable attention [72]. Furthermore, chitosan, COS and glucosammine (GlcN), obtained by chitin deacetylase action, are products with enormous biotechnological value; they have a volumetric expected market demand, in 2022, of tens of thousands of tons, finding application in several sectors such as food, medicine, pharma, water treatment, and cosmetic industries [73][74]. CDAs and CODs are metallo-enzymes classified as CE4 enzymes in the CAZy database, with the exceptions of CODs from archaea that belong to the CE14 family [75]. Although CDAs of fungal origin have been the most studied, recently, many other CDAs, and CODs from bacteria and archaea have also been investigated [76].

ArCE4A, a CDA from the marine gram-positive bacterium Arthrobacter sp. AW19M34-1, was studied by Tuveng et al. [65]. ArCE4A has broad substrate specificity, working on COS, chitosan, chitin, and acetyl xylan. Its engineered version with improved catalytic efficiency against crystalline α-chitin showed potential industrial applications for the production of chitosan, and deacetylated COS [77]. BaCDA, a CDA from Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22 isolated from sea sediment, was active against chitin, and COS [78]. Its maximum thermostability was detected in the presence of 1 M NaCl at 50 °C and pH 7.0, with 75% residual activity at pH 6.0 and 8.0. Due to its extremophilic nature, BaCDA is considered a promising candidate for industrial exploitation. In addition, terrestrial microorganisms are endowed with chitin deacetylase activity. A CDA, from Bacillus licheniformis, revealed biotechnologically relevant properties, being maximally active at 50 °C and pH 7.0, and maintaining a residual activity of 50% at 70 °C and pH 6.0 and 8.0 [79]. Chitin deacetylases, active exclusively on diacetylchitobiose (GluNAc)2 and acetylglucosammine, were studied from Archaea such as Thermococcus kodakaararensis KOD1 by Tanaka et al. [80]. The intracellular enzyme (Tk-Dac), a member of the CE14 family, showed biotechnologically relevant features, such as optimal pH, and temperature of 8.5 and 75 °C, respectively.

A deacetylase activity with similar characteristics, but with an optimum pH of 7.5, was found from Pyrococcus horikoshii (PhDac) [81]. This property, favorable for the production of N-glucosamine (GlcN), a compound stable under acidic conditions, was improved in the engineered PhDac mutant, showing an optimum pH of 6.0 and a higher specific activity and conversion rate for GlcNAc, compared with the native form [82].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms232315254

References

- Rojas, L.F.; Zapata, P.; Ruiz-Tirado, L. Agro-industrial waste enzymes: Perspectives in circular economy. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 34, 100585.

- Sahay, S. Deconstruction of lignocelluloses: Potential biological approaches. In Handbook of Biofuels; Sahay, S., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 207–232.

- Levasseur, A.; Drula, E.; Lombard, V.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. Expansion of the enzymatic repertoire of the CAZy database to integrate auxiliary redox enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 41.

- Laurent, C.V.F.P.; Sun, P.; Scheiblbrandner, S.; Csarman, F.; Cannazza, P.; Frommhagen, M.; van Berkel, W.J.H.; Oostenbrink, C.; Kabel, M.A.; Ludwig, R. Influence of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase active site segments on activity and affinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6219.

- Suzuki, K.; Suzuki, M.; Taiyoji, M.; Nikaidou, N.; Watanabe, T. Chitin Binding Protein (CBP21) in the culture supernatant of Serratia marcescens 2170. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998, 62, 128–135.

- Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Houston, D.R.; Riemen, A.H.; Eijsink, V.G.; van Aalten, D.M. Crystal structure and binding properties of the Serratia marcescens chitin-binding protein CBP21. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 11313–11319.

- Forsberg, Z.; Mackenzie, A.K.; Sorlie, M.; Rohr, A.K.; Helland, R.; Arvai, A.S.; Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Eijsink, V.G. Structural and functional characterization of a conserved pair of bacterial cellulose-oxidizing lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8446–8451.

- Bentley, S.D.; Chater, K.F.; Cerdeno-Tarraga, A.M.; Challis, G.L.; Thomson, N.R.; James, K.D.; Harris, D.E.; Quail, M.A.; Kieser, H.; Harper, D.; et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 2002, 417, 141–147.

- Rodrigues, K.B.; Macedo, J.K.A.; Teixeira, T.; Barros, J.S.; Araujo, A.C.B.; Santos, F.P.; Quirino, B.F.; Brasil, B.; Salum, T.F.C.; Abdelnur, P.V.; et al. Recombinant expression of Thermobifida fusca E7 LPMO in Pichia pastoris and Escherichia coli and their functional characterization. Carbohydr. Res. 2017, 448, 175–181.

- Russo, D.A.; Zedler, J.A.Z.; Wittmann, D.N.; Mollers, B.; Singh, R.K.; Batth, T.S.; van Oort, B.; Olsen, J.V.; Bjerrum, M.J.; Jensen, P.E. Expression and secretion of a lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase by a fast-growing cyanobacterium. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 74.

- Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, H. Heterologous expression and characterization of a novel lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase from Natrialbaceae archaeon and its application for chitin biodegradation. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 354, 127174.

- Arab-Jaziri, F.; Bissaro, B.; Tellier, C.; Dion, M.; Fauré, R.; O’Donohue, M.J. Enhancing the chemoenzymatic synthesis of arabinosylated xylo-oligosaccharides by GH51 α-l-arabinofuranosidase. Carbohydr. Res. 2015, 401, 64–72.

- Liu, G.; Qu, Y. Integrated engineering of enzymes and microorganisms for improving the efficiency of industrial lignocellulose deconstruction. Eng. Microbiol. 2021, 1, 100005.

- Numan, M.T.; Bhosle, N.B. α-l-Arabinofuranosidases: The potential applications in biotechnology. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 33, 247–260.

- Kobayashi, M.; Kumagai, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yasui, H.; Kishimura, H. Identification of a key enzyme for the hydrolysis of β-(1→3)-xylosyl linkage in red alga dulse xylooligosaccharide from Bifidobacterium adolescentis. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 174.

- Thakur, A.; Sharma, K.; Goyal, A. α-l-Arabinofuranosidase: A potential enzyme for the food industry. In Green Bio-processes: Enzymes in Industrial Food Processing; Parameswaran, B., Varjani, S., Raveendran, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 229–244.

- Wilkens, C.; Andersen, S.; Dumon, C.; Berrin, J.G.; Svensson, B. GH62 arabinofuranosidases: Structure, function and applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 792–804.

- Limsakul, P.; Phitsuwan, P.; Waeonukul, R.; Pason, P.; Tachaapaikoon, C.; Poomputsa, K.; Kosugi, A.; Ratanakhanokchai, K. A novel multifunctional arabinofuranosidase/endoxylanase/beta-xylosidase GH43 enzyme from Paenibacillus curdlanolyticus B-6 and its synergistic action to produce arabinose and xylose from cereal arabinoxylan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0173021.

- Atalah, J.; Cáceres-Moreno, P.; Espina, G.; Blamey, J.M. Thermophiles and the applications of their enzymes as new biocatalysts. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 280, 478–488.

- Wang, W.; Mai-Gisondi, G.; Stogios, P.J.; Kaur, A.; Xu, X.; Cui, H.; Turunen, O.; Savchenko, A.; Master, E.R. Elucidation of the molecular basis for arabinoxylan-debranching activity of a thermostable family GH62 α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Streptomyces thermoviolaceus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5317–5329.

- Olajide, A.O.; Adesina, F.C.; Onilude, A.A. A thermostable and alkalitolerant arabinofuranosidase by Streptomyces lividus. Biotechnol. J. Int. 2020, 24, 35–47.

- Sevim, E.; Inan Bektas, K.; Sevim, A.; Canakci, S.; Sahin, I.; Belduz, A.O. Purification and characterization of α-L-arabinofuranosidases from Geobacillus stearothermophilus strain 12. Biologia 2017, 72, 831–839.

- İlgü, H.; Sürmeli, Y.; Şanlı-Mohamed, G. A thermophilic α-l-Arabinofuranosidase from Geobacillus vulcani GS90: Heterologous expression, biochemical characterization, and its synergistic action in fruit juice enrichment. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1627–1636.

- Xie, J.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, L.; Pei, J.; Xiao, W.; Ding, G.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J. Characterization of a novel arabinose-tolerant alpha-L-arabinofuranosidase with high ginsenoside Rc to ginsenoside Rd bioconversion productivity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 647–660.

- Morana, A.; Paris, O.; Maurelli, L.; Rossi, M.; Cannio, R. Gene cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of a bi-functional β-D-xylosidase/α-l-arabinosidase from Sulfolobus solfataricus involved in xylan degradation. Extremophiles 2007, 11, 123–132.

- Saleh, M.A.; Mahmud, S.; Albogami, S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Paul, G.K.; Islam, S.; Dutta, A.K.; Uddin, M.S.; Zaman, S. Biochemical and molecular dynamics study of a novel GH43 alpha-l-arabinofuranosidase/beta-xylosidase from Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus DSM8903. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 810542.

- Zhang, X.J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.L.; Li, Y.H. Contributions and characteristics of two bifunctional GH43 β-xylosidase /α-L-arabinofuranosidases with different structures on the xylan degradation of Paenibacillus physcomitrellae strain XB. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 253, 126886.

- Underlin, E.N.; Frommhagen, M.; Dilokpimol, A.; van Erven, G.; de Vries, R.P.; Kabel, M.A. Feruloyl esterases for biorefineries: Subfamily classified specificity for natural substrates. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 332.

- Biely, P.; Singh, S.; Puchart, V. Towards enzymatic breakdown of complex plant xylan structures: State of the art. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1260–1274.

- Olson, D.G.; McBride, J.E.; Joe Shaw, A.; Lynd, L.R. Recent progress in consolidated bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 396–405.

- Bronnenmeier, K.; Meissner, H.; Stocker, S.; Staudenbauer, W.L. α-D-glucuronidases from the xylanolytic thermophiles Clostridium stercorarium and Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum. Microbiology 1995, 141, 2033–2040.

- Choi, I.-D.; Kim, H.-Y.; Choi, Y.-J. Gene cloning and characterization of α-glucuronidase of Bacillus stearothermophilus No. 236. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000, 64, 2530–2537.

- Zaide, G.; Shallom, D.; Shulami, S.; Zolotnitsky, G.; Golan, G.; Baasov, T.; Shoham, G.; Shoham, Y. Biochemical characterization and identification of catalytic residues in α-glucuronidase from Bacillus stearothermophilus T-6. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 3006–3016.

- Ruile, P.; Winterhalter, C.; Liebl, W. Isolation and analysis of a gene encoding α-glucuronidase, an enzyme with a novel primary structure involved in the breakdown of xylan. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 23, 267–279.

- Suresh, C.; Kitaoka, M.; Hayashi, K. A thermostable non-xylanolytic α-glucuronidase of Thermotoga maritima MSB8. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2003, 67, 2359–2364.

- Malgas, S.; Mafa, M.S.; Mkabayi, L.; Pletschke, B.I. A mini review of xylanolytic enzymes with regards to their synergistic interactions during hetero-xylan degradation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 187.

- Wong, D.W.S. Feruloyl esterase. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2006, 133, 87–112.

- Oliveira, D.M.; Mota, T.R.; Oliva, B.; Segato, F.; Marchiosi, R.; Ferrarese-Filho, O.; Faulds, C.B.; dos Santos, W.D. Feruloyl esterases: Biocatalysts to overcome biomass recalcitrance and for the production of bioactive compounds. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 278, 408–423.

- Zduńska, K.; Dana, A.; Kolodziejczak, A.; Rotsztejn, H. Antioxidant properties of ferulic acid and its possible application. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 31, 332–336.

- Antonopoulou, I.; Leonov, L.; Jütten, P.; Cerullo, G.; Faraco, V.; Papadopoulou, A.; Kletsas, D.; Ralli, M.; Rova, U.; Christakopoulos, P. Optimized synthesis of novel prenyl ferulate performed by feruloyl esterases from Myceliophthora thermophila in microemulsions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 3213–3226.

- Esteban-Torres, M.; Landete José, M.; Reverón, I.; Santamaría, L.; de las Rivas, B.; Muñoz, R. A Lactobacillus plantarum esterase active on a broad range of phenolic esters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3235–3242.

- Deng, H.; Jia, P.; Jiang, J.; Bai, Y.; Fan, T.-P.; Zheng, X.; Cai, Y. Expression and characterisation of feruloyl esterases from Lactobacillus fermentum JN248 and release of ferulic acid from wheat bran. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 272–277.

- Song, Y.R.; Baik, S.H. Molecular cloning, purification, and characterization of a novel thermostable cinnamoyl esterase from Lactobacillus helveticus KCCM 11223. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 47, 496–504.

- Kim, J.-H.; Baik, S.-H. Properties of recombinant novel cinnamoyl esterase from Lactobacillus acidophilus F46 isolated from human intestinal bacterium. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 116, 9–15.

- Ay Sal, F.; Colak, D.N.; Guler, H.I.; Canakci, S.; Belduz, A.O. Biochemical characterization of a novel thermostable feruloyl esterase from Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius DSM 2542T. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 4385–4395.

- Rakotoarivonina, H.; Hermant, B.; Chabbert, B.; Touzel, J.-P.; Remond, C. A thermostable feruloyl-esterase from the hemicellulolytic bacterium Thermobacillus xylanilyticus releases phenolic acids from non-pretreated plant cell walls. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 541–552.

- Kmezik, C.; Bonzom, C.; Olsson, L.; Mazurkewich, S.; Larsbrink, J. Multimodular fused acetyl–feruloyl esterases from soil and gut Bacteroidetes improve xylanase depolymerization of recalcitrant biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 60.

- Blum, D.L.; Kataeva, I.A.; Li, X.-L.; Ljungdahl, L.G. Feruloyl esterase activity of the Clostridium thermocellum cellulosome can be attributed to previously unknown domains of XynY and XynZ. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 1346–1351.

- Prates, J.A.M.; Tarbouriech, N.; Charnock, S.J.; Fontes, C.M.G.A.; Ferreira, L.s.M.A.; Davies, G.J. The structure of the feruloyl esterase module of xylanase 10B from Clostridium thermocellum provides insights into substrate recognition. Structure 2001, 9, 1183–1190.

- Arnling Bååth, J.; Mazurkewich, S.; Knudsen, R.M.; Poulsen, J.-C.N.; Olsson, L.; Lo Leggio, L.; Larsbrink, J. Biochemical and structural features of diverse bacterial glucuronoyl esterases facilitating recalcitrant biomass conversion. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 213.

- Hämäläinen, V.; Grönroos, T.; Suonpää, A.; Heikkilä, M.W.; Romein, B.; Ihalainen, P.; Malandra, S.; Birikh, K.R. Enzymatic processes to unlock the lignin value. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 20.

- Mosbech, C.; Holck, J.; Meyer, A.S.; Agger, J.W. The natural catalytic function of CuGE glucuronoyl esterase in hydrolysis of genuine lignin–carbohydrate complexes from birch. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 71.

- Ohbuchi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Azumi, N.; Sakaino, M. Structual analysis of neutral and acidic xylooligosaccharides from hardwood kraft pulp, and their utilization by intestinal bacteria in vitro. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 2070–2076.

- De Graaf, M.; Nevalainen, T.J.; Scheeren, H.W.; Pinedo, H.M.; Haisma, H.J.; Boven, E. A methylester of the glucuronide prodrug DOX-GA3 for improvement of tumor-selective chemotherapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 2273–2281.

- Li, X.-L.; Špániková, S.; de Vries, R.P.; Biely, P. Identification of genes encoding microbial glucuronoyl esterases. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4029–4035.

- De Santi, C.; Willassen, N.P.; Williamson, A. Biochemical characterization of a family 15 carbohydrate esterase from a bacterial marine arctic metagenome. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159345.

- Aurilia, V.; Martin, J.C.; McCrae, S.I.; Scott, K.P.; Rincon, M.T.; Flint, H.J. Three multidomain esterases from the cellulolytic rumen anaerobe Ruminococcus flavefaciens 17 that carry divergent dockerin sequences. Microbiology 2000, 146, 1391–1397.

- Biely, P.; Malovíková, A.; Uhliariková, I.; Li, X.-L.; Wong, D.W.S. Glucuronoyl esterases are active on the polymeric substrate methyl esterified glucuronoxylan. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2334–2339.

- Krska, D.; Mazurkewich, S.; Brown, H.A.; Theibich, Y.; Poulsen, J.-C.N.; Morris, A.L.; Koropatkin, N.M.; Lo Leggio, L.; Larsbrink, J. Structural and functional analysis of a multimodular hyperthermostable xylanase-glucuronoyl esterase from Caldicellulosiruptor kristjansonii. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 2206–2220.

- Arnling Bååth, J.; Mazurkewich, S.; Poulsen, J.-C.N.; Olsson, L.; Lo Leggio, L.; Larsbrink, J. Structure and function analyses reveal that a glucuronoyl esterase from Teredinibacter turnerae interacts with carbohydrates and aromatic compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6635–6644.

- Souza, C.P.; Almeida, B.C.; Colwell, R.R.; Rivera, I.N.G. The Importance of chitin in the marine environment. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011, 13, 823–830.

- Coutinho, P.M.; Deleury, E.; Henrissat, B. The families of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the genomic era. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2003, 50, 241–244.

- Naveed, M.; Phil, L.; Sohail, M.; Hasnat, M.; Baig, M.M.F.A.; Ihsan, A.U.; Shumzaid, M.; Kakar, M.U.; Mehmood Khan, T.; Akabar, M.D.; et al. Chitosan oligosaccharide (COS): An overview. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 827–843.

- Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Horn, S.J.; Sørlie, M.; Eijsink, V.G.H. The chitinolytic machinery of Serratia marcescens—A model system for enzymatic degradation of recalcitrant polysaccharides. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 3028–3049.

- Tuveng, T.R.; Hagen, L.H.; Mekasha, S.; Frank, J.; Arntzen, M.Ø.; Vaaje-Kolstad, G.; Eijsink, V.G.H. Genomic, proteomic and biochemical analysis of the chitinolytic machinery of Serratia marcescens BJL200. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2017, 1865, 414–421.

- Doan, C.T.; Tran, T.N.; Wang, S.-L. Production of thermophilic chitinase by Paenibacillus sp. TKU052 by bioprocessing of chitinous fishery wastes and its application in N-acetyl-D-glucosamine production. Polymers 2021, 13, 3048.

- Sousa, A.J.S.; Silva, C.F.B.; Sousa, J.S.; Monteiro, J.E.; Freire, J.E.C.; Sousa, B.L.; Lobo, M.D.P.; Monteiro-Moreira, A.C.O.; Grangeiro, T.B. A thermostable chitinase from the antagonistic Chromobacterium violaceum that inhibits the development of phytopathogenic fungi. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2019, 126, 50–61.

- Chen, L.; Wei, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.-H. An archaeal chitinase with a secondary capacity for catalyzing cellulose and its biotechnological applications in shell and straw degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1253.

- Sorokin, D.Y.; Toshchakov, S.V.; Kolganova, T.V.; Kublanov, I.V. Halo(natrono)archaea isolated from hypersaline lakes utilize cellulose and chitin as growth substrates. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 942.

- Nishitani, Y.; Horiuchi, A.; Aslam, M.; Kanai, T.; Atomi, H.; Miki, K. Crystal structures of an archaeal chitinase ChiD and its ligand complexes. Glycobiology 2018, 28, 418–426.

- Grifoll-Romero, L.; Pascual, S.; Aragunde, H.; Biarnés, X.; Planas, A. Chitin deacetylases: Structures, specificities, and biotech applications. Polymers 2018, 10, 352.

- Bonin, M.; Sreekumar, S.; Cord-Landwehr, S.; Moerschbacher, B.M. Preparation of defined chitosan oligosaccharides using chitin deacetylases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7835.

- Cheung, R.C.; Ng, T.B.; Wong, J.H.; Chan, W.Y. Chitosan: An update on potential biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5156–5186.

- Zhang, J.; Yan, N. Production of glucosamine from chitin by co-solvent promoted hydrolysis and deacetylation. ChemCatChem 2017, 9, 2790–2796.

- Mine, S.; Niiyama, M.; Hashimoto, W.; Ikegami, T.; Koma, D.; Ohmoto, T.; Fukuda, Y.; Inoue, T.; Abe, Y.; Ueda, T.; et al. Expression from engineered Escherichia coli chromosome and crystallographic study of archaeal N,N′-diacetylchitobiose deacetylase. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 2584–2596.

- Huang, Z.; Lv, X.; Sun, G.; Mao, X.; Lu, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Chitin deacetylase: From molecular structure to practical applications. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufact. 2022, 2, 271–284.

- Ding, Z.; Ahmed, S.; Hang, J.; Mi, H.; Hou, X.; Yang, G.; Huang, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S.; et al. Rationally engineered chitin deacetylase from Arthrobacter sp. AW19M34-1 with improved catalytic activity toward crystalline chitin. Carbohyd. Polym. 2021, 274, 118637.

- Pawaskar, G.M.; Raval, K.; Rohit, P.; Shenoy, R.P.; Raval, R. Cloning, expression, purification and characterization of chitin deacetylase extremozyme from halophilic Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 515.

- Bhat, P.; Pawaskar, G.-M.; Raval, R.; Cord-Landwehr, S.; Moerschbacher, B.; Raval, K. Expression of Bacillus licheniformis chitin deacetylase in E. coli pLysS: Sustainable production, purification and characterisation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 1008–1013.

- Tanaka, T.; Fukui, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Atomi, H.; Imanaka, T. Concerted action of diacetylchitobiose deacetylase and exo-beta-D-glucosaminidase in a novel chitinolytic pathway in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 30021–30027.

- Mine, S.; Ikegami, T.; Kawasaki, K.; Nakamura, T.; Uegaki, K. Expression, refolding, and purification of active diacetylchitobiose deacetylase from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012, 84, 265–269.

- Huang, Z.; Mao, X.; Lv, X.; Sun, G.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Engineering diacetylchitobiose deacetylase from Pyrococcus horikoshii towards an efficient glucosamine production. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 334, 125241.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!