Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

Gliomas are the most common and aggressive primary brain tumors. Gliomas carry a poor prognosis because of the tumor’s resistance to radiation and chemotherapy leading to nearly universal recurrence. Large-scale genomic research have allowed for the development of more targeted therapies to treat glioma.

- glioma

- biomarkers

- genomics

- prognosis

1. Introduction

Gliomas are the most common and aggressive primary brain tumors, with glioblastoma (GBM) resulting in a median survival rate of ~15 months and a 5-year survival rate of 10% [1]. The poor prognosis of glioma and GBM in particular is multifactorial, involving resistance to radiation and chemotherapy, morphological and genetic heterogeneity within individual tumors, tumor alteration over time, and stem cell contribution to resistance, all resulting in nearly universal recurrence [1]. The current standard of care management of glioma involves maximal surgical resection followed by radiotherapy with concurrent and/or sequential and adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) [1,2]. Radioresistant and chemo-resistant glioma stem cells (GSCs) may in theory be targeted using novel therapies aiming to reduce the risk of tumor recurrence [3,4]. Due to molecular heterogeneity, targeted therapies using these subtypes have not become standard of care due to a lack of precision in patient selection [5]. Given the ability to leverage omic information, a more personalized approach to target specific GSCs might prove to be more effective in the treatment of gliomas. Classification methods employing genomic data extracted from GSCs may also aid in targeting treatment. Previous classification efforts of GBM tumors based on the IDH gene and methylation of the MGMT promoter with respect to clinical value have been described [6]. Recent advances in large-scale genomic research techniques and epigenomic studies involving repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA), and others could allow for the development of more targeted techniques to treat glioma; however, not all identified genomic signals translate into tumoral or proteomic alterations, and likely only a subset of these connect to clinical tumor behaviors and outcomes secondary to widespread pathway redundancy and secondary heterogeneity that is as yet poorly understood. The high cost of genomic analysis also means that not all patients can benefit from sequencing, diminishing data in this space and limiting future personalized approaches in management. AI may enable the identification of biological patterns in large-scale data to move towards the integration of omic data streams, imaging, and clinical factors via robust, realistically obtainable biomarkers [7,8,9,10,11].

2. Molecular Alterations in Glioma

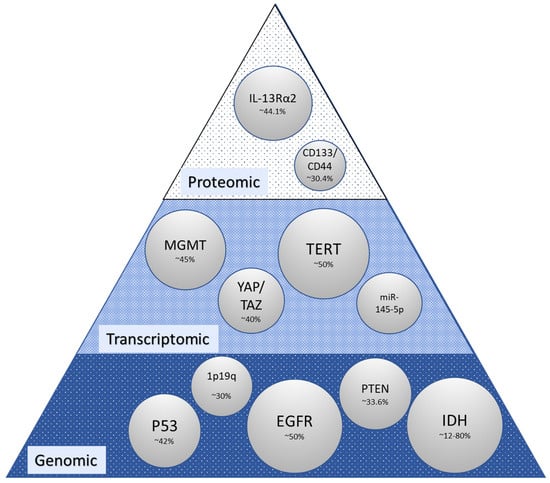

Reported alterations in glioma are broadly categorized as genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic. Their frequency is highly heterogenous (Figure 1; bubble size indicates alteration frequency reported in glioma in the current literature), and robust connections between these planes are as yet lacking. The most significant points of discussion in this area are molecular subclasses with significant prognostic value (e.g., proneural, neural, classical, and mesenchymal), which were initially identified in 2010 and have been refined since [5,12,13]. Molecular subclasses initially identified four subsets with genomic alterations that correlated to survival. Within this initial classification, proneural and neural patients had the best outcomes, classical had intermediate prognosis, and mesenchymal had the worst outcomes [14]. The proneural subtype has more frequent mutations in PDGFRA (platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha), the neural subtype has frequent mutations in CD44 and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), classical has frequent EGFR amplification, while the mesenchymal subtype has NFI (neurofibromatosis type 1) and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) mutations [5,13]. Furthermore, recurrent tumors shift toward the Mes subtype with the worst outcome [5]. Markers such as MGMT (O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase) likely reflect alterations that cross several omic boundaries. MGMT is one of the most widely studied markers in glioblastoma. Some studies show no association between the MGMT promoter and GBM’s molecular markers such as ATRX (ATP-dependent helicase), IDH (isocitrate dehydrogenase), p53, and Ki67 [15]. However, patients with a methylated MGMT promoter benefit from TMZ [2,16] as compared to those without a methylated MGMT promoter. The MGMT promoter is methylated in 45% of GBM and is associated with a prolonged overall progression-free survival [17].

The most clinically significant gene researched to date is the IDH gene which codes for the isocitrate dehydrogenase enzyme [27]. IDH genes are responsible for the intramitochondrial enzyme with three intracellular forms. IDH mutations were found in 12% of GBM patients and 80% of glioma patients in a cohort at Duke University [26]. Patients with the IDH1 gene mutation have been linked to improved intracellular response to TMZ when compared with individuals with the wild-type IDH1 gene [6]. However, IDH1 mutation status does not predict progression-free survival [28,29]. Codeletion of gene 1p19q is associated with a better response to radiation therapy and chemotherapy and longer progression-free survival. This codeletion is present in around 30–50% of gliomas [22]. The EGFR gene is an oncogene in the RTK signaling pathway that encodes cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase involved in DNA transcription, anti-apoptosis, angiogenesis, and cellular proliferation [30]. EGFR amplification is present in approximately 40–50% of primary GBMs [23]. The EGFRvIII mutation and EGFR amplification in particular have been shown to have contradictory clinical results [12]. YAP and TAZ transcription coactivators are highly expressed in EGFR-amplified/mutant GBM cells. Disrupting YAP/TAZ-mediated transcription can induce apoptosis and reduce proliferation in EGFR-amplified cells [31]. Altered expression of YAP and TAZ occurs in 40% of gliomas [31].

TP53 is a tumor suppressor gene in the p53 signaling pathway [27]. This pathway has been implicated in cell invasion, migration, proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and cancer cell stemness [32]. TP53 has a mutation frequency of 42% [23]. The p53 signaling pathway is downregulated in 84% of GBM patients [32]. Micro RNA (miRNA) and long non-coding RNA (ncRNA) are also responsible for regulating various pathways in glioma including the p53 pathways responsible for tumor suppression [32]. The expression of various miRNAs and ncRNAs is found to regulate various forms of GBM. Specifically, the miRNA miR-145-5p is a highly reliable diagnostic indicator of GBM [21]. High levels of miR-145-5p expression are linked to longer overall survival times compared to lower levels [21]. MiR-145-5p does not have data alteration frequency yet.

PTEN is a tumor suppressor gene in the PI3K signaling pathway [27]. An analysis of TCGA data identified mutated PTEN in 33% of GBM [23]. PTEN is responsible for regulating glucose metabolism through the P13K-AKT pathway with deletion correlating to poor prognosis in GBM patients [33]. Mutations of the PI3K/mTOR pathway occur in nearly 50% of GBMs [3]. The telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene promoter mutation was found to be in 80.3% of primary GBM and 28.6% of secondary GBM and found to predict overall poor survival in patients who had incomplete resections and no temozolomide chemotherapy [34]. The TERT promoter mutation in combination with EGFR amplification and IDH mutation status improves the prognostic classification of GBMs [35]. NF1 is a tumor suppressor gene in the MAPK signaling pathways [36]. In mesenchymal tumors, the NF1 protein is downregulated which upregulates the MAPK signaling pathways [6]. The P13K-AKT pathways are frequently deregulated through NF1 and PTEN co-mutation in the mesenchymal subtype [5]. The CD44 genes encode the transmembrane glycoprotein and have been known for regulating tumorigenesis [37]. High expression of CD44 leads to cancer cell proliferation, motility, and survival and promotes cancer metastasis [38]. CD133 is co-expressed with CD44 and linked to similar molecular features [19]. IL-13Ra2 is an interleukin receptor that is overexpressed in over 60% of GBM and 44.1% of gliomas [39]. Clinical trials have found immunotherapies targeting the IL-13Ra2 receptor to be effective [39].

In addition, epigenetic and translational modifications including histone post-translational modifications play a significant role in GBM development and progression [18]. Enzymes such as histone deacetylase and demethylates (HDMTs/KDMTs) have been found to be deregulated in GBM. Of note are the enzymes lysine and arginine methyltransferases (G9a, SUV39H1, and SETDB1), acetyltransferases, and deacetylases (KAT6A, SIRT2, SIRT7, HDAC4, 6, 9) that are dysregulated in GBM but more data are needed before these enzymes become clinically relevant [40]. Based on currently available TCGA and CGGA data, the most frequently reported molecular/genomic features in glioma are IDH, TP53, ATRX, PTEN, EGFR, CIC, MUC16, PI3K3CA, NF1, PIK3R1, FUBP1, TB1, NOTCH1, and TERT (Tasci et al., unpublished data) [41], and given their capture and potential for analysis, these can help make connections to MGMT, IDH, and other markers and clinical outcomes. Still, there is no clear relationship between IDH1, p53, and MGMT alterations, making analysis on glioma difficult. Furthermore, it should be noted that both MGMT and IDH status are often not available for analysis in data sets with greater than 40% of cohorts missing MGMT methylation status [42], and missing data are thus not analyzed nor easily or transparently recognized. Using deep learning methods and radiomic features to predict missing data such as MGMT methylation status has shown promise; however, more research on deep learning models and molecular models is needed before they can be applied in clinical decision making [43]. Previous attempts at glioma classification including by Verhaak et al. [5] did not carry over into the clinic even though they identified important associations, in part due to cost but also due to a lack of clear connection to other markers such as MGMT and IDH which are actively being measured in the clinic and, more significantly, because of a lack of connection to clinical features that define the outcome and clinical decision making in the real world. Another important facet of the discussion of linking clinical outcomes and molecular/genomic features is the question of how AI can learn from existing data of which current analyses struggle to compare different measures, as evidenced by comparing expression data to mutation data to downstream omic data that is dynamically regulated in an area of extreme biological heterogeneity where genomic classification does not yet clearly connect to pathology nor molecular or clinical endpoints [6,16,44].

3. Clinical and Management Features of Significance in Glioma

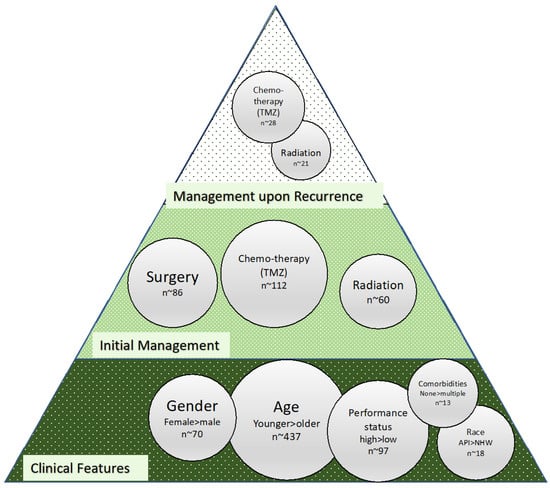

Clinical and disease features are most often employed as a means of elucidating prognosis in glioma. The patient-related factors most frequently associated with prognosis are age, performance status, gender, race, and comorbidities (Figure 2). The relationship between age and prognosis has benefited from several analyses including a recent analysis of the SEER database from 2000 to 2018 wherein a nonlinear relationship was revealed with the hazard ratio of death increasing to 10 years, then decreasing to 23 years, and subsequently becoming J-shaped with increasing age [54] in contrast to previously described groupings based on smaller groups of patients, where the age-prognosis relationship was described more rigidly along age lines [55], and older studies where age was dichotomized to less than or greater than 50 years old such as in the context of traditional recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) [56]. There is also reported intersectionality between age and gender and between these clinical features and molecular markers with GFAP, EMA, MGMT, P53, NeuN, Oligo2, EGFR, VEGF, IDH1, Ki-67, PR, CD3, H3K27M, TS, and 1p/19q status included in the age group classification by Lin et al. 2020 [55]. Gender-related prognosis differences and associated molecular features support connections to outcomes [57,58]. Molecular differences associated with gender were reported for XIST, PUDP, ZFX, JPX, KDM6A, and TSIX in females and PRKY, RPS4Y2, PCDH11Y, EIF1AY, RPS4Y1, and ZFY in males when the analysis was carried out on GBM and LGG [58]. With respect to race and ethnicity, significant intersectionality exists between the risk of glioma, health disparities, and genetic heterogeneity, all of which impact prognosis [59], with recent data showing similar mortality risks for black, Hispanic, and white patients and superior survival reported in non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander patients [60], and SEER data from 2002 to 2014 showing non-Hispanic white patients having higher incidence and lower survival as compared to other ethnic groups [61]. An association between genetic pathways underlying glioma with white patients having a higher risk for glioma than non-white patients and gliomas from white patients less likely to have p53 mutation was reported in 2001 [62]. Increasingly, data are becoming available in which molecular features with links to race have been identified, including with respect to TP53 and EGFR [63]. However, a clear relationship between molecular alterations and ethnicity/race is lacking. Performance status has been extensively reported on in glioma patients as a prognostic marker [64,65,66]. It is a component of RPA but is also often poorly captured and less likely to have an immediate connection to molecular features even as it may well connect to comorbidities, another clinical facet that is poorly captured but may have a molecular signature. Additional clinical features related to the upfront management of glioma begin with the extent of resection [67]; administration of chemotherapy, in particular the extent of adjuvant temozolomide in terms of the number of cycles; and additional management upon recurrence (Figure 2) for which molecular markers are not specifically identified. Figure 2 indicates clinical features with significant prognostic value for patients with glioma and current management protocols.

Metabolic markers can provide additional information on GBM’s response to therapies and progression. Previous research has found a significant correlation between mutations found in GBM and the tumor’s metabolic fingerprint [68]. Metabolic markers in conjunction with genomic, radiomic, and proteomic data should be used to develop clinical models. To overcome the heterogeneity of glioma, several AI algorithm application tools have been used. In particular, combining imaging techniques (i.e., CT, MRI, PET-CT) with metabolic markers and proteome data has been shown to yield useful information for clinical applications [69]. Current models predict overall survival, progression-free survival, and molecular subtypes of high-grade glioma as well as genetic alterations. Models using radiomic features have been shown to outperform models using clinical data—particularly patient age, the Karnofsky performance scale, surgical resection, and genetic alterations—in GBM outcome prediction [70]. Using ensemble models, models using more than one machine learning algorithm, as opposed to models using only one machine learning algorithm, can help overcome the lack of standardization of radiomic features. Pasquini et al. showed that certain radiomic features can be used to predict molecular markers, indicating a correlation between imaging data and tumor histology [71]. Previous prognostic models using stemness-based classification can be used to guide treatment decisions in selecting potential responders for preferential use of immunotherapy [72].

The thought process embedded in clinical decision making is ultimately a byproduct of the reported data (Figure 2) and available markers in the clinic (MGMT, IDH, and others), these linking to the overall cost of care which translates into the type of data that is ultimately available for AI-driven approaches and which will be discussed next.

Figure 2. Bubble size for clinical features and treatments was determined based on PubMed search findings. MeSH terms used in the search for clinical features were “glioma”, “prognosis”, and “indicates” and for clinical features either “race”, “sex”, “performance status”, “age”, or “sex.” Terms used for initial management therapies were “glioma”, “prognosis”, “indicates”, “initial”, and either “surgery”, “radiation”, or “chemotherapy”. For recurrent tumor treatment bubbles, the same search was used with the term “recurrent” instead of “initial.” All searches were filtered for only articles in the last 10 years.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines10123029

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!