Cancer ranks as the second leading cause of death worldwide, and, being a genetic disease, it is highly heritable. Over the past few decades, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified many risk-associated loci harboring hundreds of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Some of these cancer-associated SNPs have been revealed as causal, and the functional characterization of the mechanisms underlying the cancer risk association has been illuminated in some instances.

- genome-wide association analysis

- single nucleotide polymorphism

- cancer

- molecular and biological mechanism

1. Functional Mechanisms of Coding Region SNPs

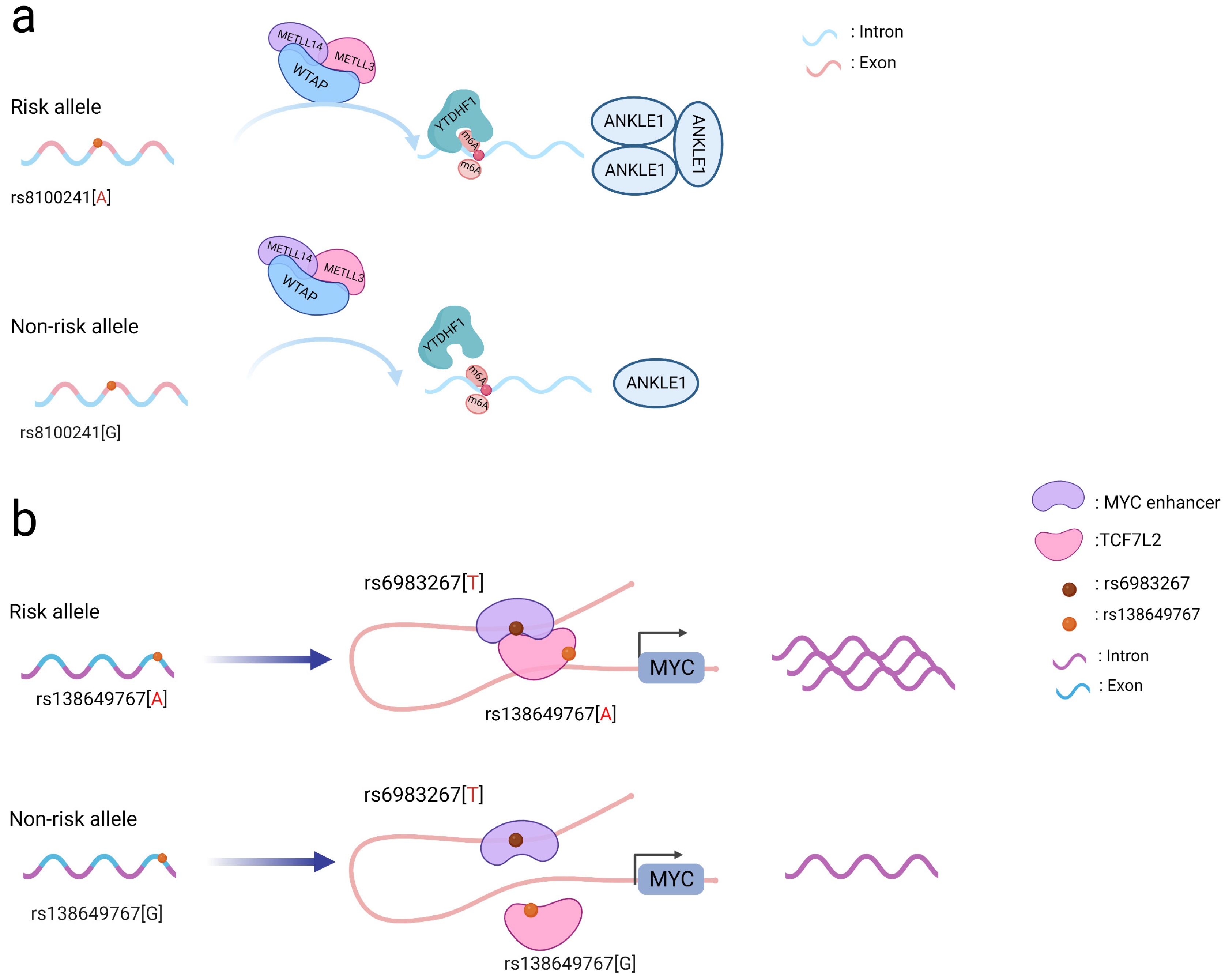

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the action mechanism employed by coding SNPs. (a) The A allele of the rs8100241 variant, which is found in the ANKLE1 second exon region, has been linked to a lower risk of CRC by increasing ANKLE1 mRNA m6A levels and thus facilitating ANKLE1 protein expression, thereby potentially functioning as a negative regulator to hinder cell growth by maintaining genomic stability. (b) Interaction between the TCF7L2 missense variant rs138649767 and a regulatory variant rs6983267 in the MYC enhancer and promoter on the expression of MYC.

Notably, coding SNPs may interact with other SNPs to produce a stronger functional role [5]. The rs138649767 A allele (Figure 1b) located in the exon region of TCF7L2 can activate the MYC enhancer containing rs6983267 allele G to promote the expression of MYC [16]. SNPs occurring in the exons and introns of SMAD7 may affect its regulation and jointly affect downstream signaling pathways involving SMAD7 and TGFβ [11]. As a result, while examining SNPs in coding regions, the interactions between them should be taken into account to better understand their functional processes.

2. Functional Mechanisms of Non-Coding Region SNPs

Accumulating evidence shows that a SNP in non-coding regions is the most common type of genetic variation in the human genome, accounting for 90% of inter-individual variation [17][18]. Depending on the location, the region can harbor a response element that is either proximal (promoter, enhancer, or super-enhancer) or distal (intergenic or intra-genic). The risk loci identified by GWAS were located in the genomic regions of cell type-specific active chromatin, and most of them were quantitative trait loci, methylation quantitative trait loci and transcription factor (TF) binding related loci. Chromatin conformational studies have helped to link regulatory regions localized by SNPs to their respective target genes [17][19][20]. These loci may be involved in gene transcription, post-transcriptional processing, translation, post-translational modifications, and other processes to regulate gene expression. Many target genes have been identified using expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) to detect the relationship between SNPs and gene expression. Non-coding SNPs can regulate the transcription of target genes by sequence-proximal (cis)- or distal (trans)-interactions. Studies have found that histone modifications in the regions of such risk SNPs are particularly abundant, especially those related to promoter and enhancer activities (H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K27ac). Most SNPs are predicted to destroy the binding motifs of specific transcription factors. For example, rs6983267 may change the binding of transcription factors such as MYC, CTCF, and TCF7L2 [21]. In addition to affecting gene transcription levels by altering transcription factor-binding sites (TFBS), non-coding SNPs also change epigenetic modifications and/or the chromatin structure to influence target gene expression. Through the above method, non-coding SNP participates in cell proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion.

2.1. Genetic Variants That Alter Promoters

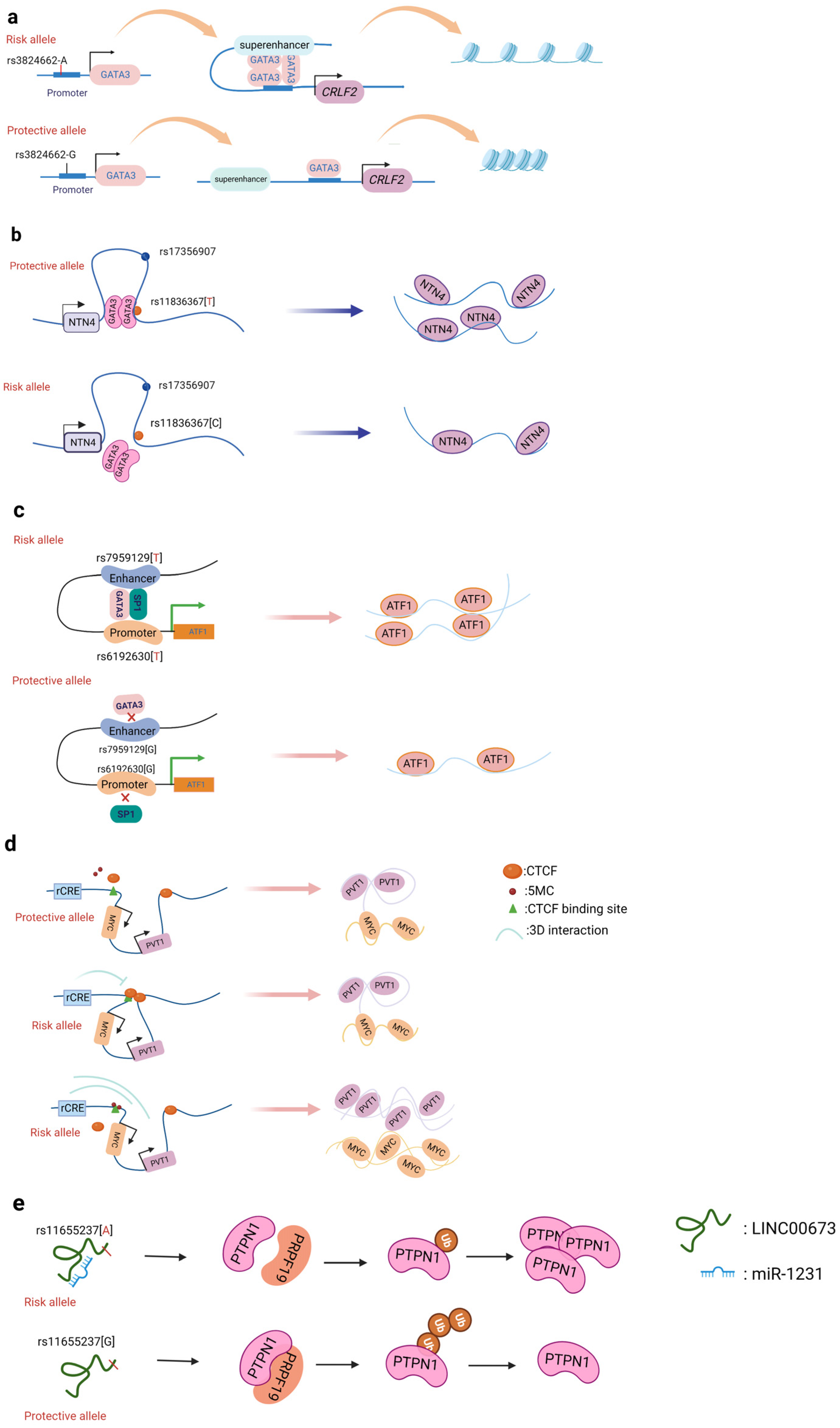

A promoter is a sequence of DNA that is recognized, bound, and serves to initiate transcription by RNA polymerase. Promoters contain variations of a conserved sequence required for the specific binding of RNA polymerase and transcription initiation. Most promoters are located upstream of the transcription initiation point of structural genes, and the promoter itself is not transcribed [22]. Promoters are located upstream of the 5’ end of a given structural gene, and they activate RNA polymerase to bind accurately to the template DNA with specificity for inducing the initiation of transcription [22]. Promoters do not control gene activity themselves; rather, gene activity is regulated by binding to proteins called transcription factors (TF). SNPs within promoter regions generally play a regulatory role by influencing the binding of such transcription factors. A recently reported example is that of the SNP rs13278062 located in the promoter of death receptor 4 (DR4) which confers an altered risk of colorectal cancer. The study revealed that the rs13278062 G>T variant changed the binding affinity of the transcription factor Sp1/NF1, increased the expression of DR4, and thus suppressed carcinogenesis and metastasis of colorectal cancer [23]. The MPO promoter SNP rs2333227 increases the malignant characteristics of colorectal cancer by changing the promoter’s affinity to AP-2α [24]. The variant SNP rs10993994 located in the upstream promoter of the gene MSMB is also found to be overrepresented in individuals with prostate cancer; this is attributed to stronger CREB binding and thus increased promoter activity [25]. Furthermore, the SNP rs11672691 is a risk locus associated with prostate cancer that is related to the lncRNA PCAT19. The non-risk variant rs11672691 and its linkage disequilibrium (LD) SNP rs887391 are more likely to bind the TFs NKX3.1 and YY1 to the PCAT19-short promoter, thereby leading to increased promoter but lower enhancer activity, which then activates PCAT19-short, and ultimately results in lower prostate cancer susceptibility [26]. SNPs in promoter regions of multiple genes, including TERT, KLHDC7A, PIDD1, and ESR1, have been discovered in breast cancer by GWAS, with reporter studies revealing that independent risk alleles change target promoter activity [27][28]. Most of the reported promoter changes exert their regulatory effects by altering TF binding. The SNP rs3824662 allele A (Figure 2a) increases chromatin accessibility by changing the TF GATA3 expression, promoting the binding of GATA3 with the CRLF promoter, and ultimately forming a chromatin loop [29].

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the action mechanism employed by non-coding SNPs. (a) The SNP rs3824662 allele A increases chromatin accessibility by inducing GATA3 expression, promoting the binding of GATA3 with the CRLF promoter, and ultimately forming a chromatin loop. (b) The NTN4 enhancer risk variant rs11836367 binds to the TF GATA3 to regulate NTN4 expression, ultimately promoting breast carcinoma initiation and progression. (c) Enhancer SNP rs7959129 risk allele G interacts with promoter SNP rs6192603 risk allele G contributing to ATF1 expression by binding TFs GATA3 and SP1. (d) The risk allele rs11986220 and higher methylation at –10 Kb synergistically function to confer a greater risk of tumor; however, when -20 Kb is hypomethylated, the function of the risk SNP is inhibited by the enhancer-blocking insulator loop mediated by CTCF. (e) The risk variant rs11655237 in LINC00673 creates a miR-1231–binding site that interferes with the expression of LINC00673 and contributes to pancreatic cancer susceptibility.

2.2. Genetic Variants That Alter Enhancers

Enhancers are regions of DNA sequence that can increase the cis-acting transcription of their target gene sequences. Enhancers each differ in their distance from their target promoter(s); in mammalian species, an enhancer can be 100 bp to Mb away from their target gene [30]. Enhancers, unlike promoters, can be found anywhere in a gene; they can be positioned either upstream or downstream of their target genes, or even within another gene’s gene body, and enhancer regulation can circumvent other genes irrespective of their orientation. Enhancers must bind to specific protein factors to enhance the transcription of their target. Enhancers generally have tissue or cell specificity, whereby they only show activity in certain cells or tissues, which is determined by the specific protein factors present in these cells or tissues [31]. Enhancers are typically recognized by the epigenetic marks H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, which are present in active enhancer elements. Conversely, H3K27me3 is regarded as a silent epigenetic mark associated with lower enhancer activity [32][33]. GWAS-identified risk loci for common illnesses are often found in non-coding areas, and many of these are thought to function as enhancers [34]. According to emerging data, these SNPs may influence gene regulation by changing the binding of important TFs to critical transcriptional enhancers [35].

2.2.1. Breast Cancer

Of all cancers, breast cancer has so far yielded the greatest number of discovered risk loci [36]. Understanding the driving mechanism(s) underlying malignant transformation provides the prospect of combating cancer recurrence and treatment resistance. Zhang et al. identified that the SNP rs4971059 resides in the sixth intron and within an active enhancer element of the TRIM46 gene. By using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination, they constructed the SNP rs4971059 with the allele G converted to allele A, thereby resulting in TRIM46 overexpression, boosting breast carcinoma cell growth, enhancing chemotherapy resistance in vitro, and hastening tumor development in vivo [37]. In addition, Yang and colleagues (Figure 2b) reported the noncoding regulatory variant rs11836367 at the NTN4 locus (12q22) and identified it to be associated with the risk of breast carcinoma as a causal variant. The rs11837367 protective T allele promotes GATA3 binding to the distal enhancer and increases NTN4 expression [38].

2.2.2. Prostate Cancer

2.2.3. Colorectal Cancer

GWAS have identified numerous colorectal cancer risk loci, but only a fraction of the target genes of these loci have been systematically interrogated. For example, Yu et al. identified a common SNP (rs7198799) in the intron of the gene CDH1. They demonstrated that the risk allele C of rs7198799 acts as an enhancer that can target the TF NFATC2 and remotely enhance ZFP90 expression [45]. A prominent mechanism by which SNP variants can affect cell-specific enhancer function is via altered TF binding, thus regulating the target gene’s expression. Tian et al. identified two risk SNPs (rs61926301 and rs79591129) located in the ATF1 promoter and first intron, respectively. These are enriched in enhancer regions and open chromatin, which are also associated with H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and ATAC-seq peaks. The two variants increase the expression of ATF1 through preferentially binding to the two TFs SP1 and GATA3 [46]. Rs174575 can act as a specific remote enhancer of FADS2 and lncRNA-AP002754.2 with the participation of the transcription factor E2F1. Interestingly, TF E2F1 can promote the expression of FADS2, form a chromatin loop, and affect the occurrence of colorectal cancer [47].

2.3. Genetic Variants That Affect Promoter–Enhancer Interactions

Promoter–enhancer interactions (PEIs) underlie differential transcriptional regulation. Several technologies (chromosome conformation capture (3C), Hi-c, and H3K27Ac-HiCHIP) allow for the study of long-range cis-regulation [48][49][50]. Promoter–enhancer interactions are essential events involved in the current theory of transcriptional control. So far, there is little evidence that PEIs are required for the transcriptional control of an enhancer’s target gene. The insertion or deletion of promoters, the absence of certain PEI-associated proteins, and the inclusion of PEI-disrupting insulators all have an effect on the expression of target genes. Tian et al. found two risk variants (rs1926301 and rs7959129) located in the ATF1 promoter and intron, respectively; the former binds the TF SP1 while the latter binds the TF GATA3 (Figure 2c). They found that these two risk sites increase the interaction between the promoter and enhancer by binding SP1 and GATA3, facilitating ATF1 expression, and conferring hereditary susceptibility to CRC [46]. Moreover, the SNP rs11672691 mediates promoter and enhancer switching in a manner dependent on different background genotypes. The risk is determined by the PCAT19-long enhancer interacting with the PCAT19-long promoter, thereby altering prostate cancer development through activating cell cycle genes [26].

2.4. Genetic Variants That Alter 3D Genome Architecture

2.5. Genetic Variants That Influence the Binding of miRNA

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14225636

References

- Ng, P.C.; Henikoff, S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3812–3814.

- Lee, P.H.; Shatkay, H. F-SNP: Computationally predicted functional SNPs for disease association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D820–D824.

- Ritchie, G.R.; Flicek, P. Computational approaches to interpreting genomic sequence variation. Genome Med. 2014, 6, 1760.

- Theodoratou, E.; Farrington, S.M.; Timofeeva, M.; Din, F.V.; Svinti, V.; Tenesa, A.; Liu, T.; Lindblom, A.; Gallinger, S.; Campbell, H.; et al. Genome-wide scan of the effect of common nsSNPs on colorectal cancer survival outcome. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 988–993.

- Timofeeva, M.N.; Kinnersley, B.; Farrington, S.M.; Whiffin, N.; Palles, C.; Svinti, V.; Lloyd, A.; Gorman, M.; Ooi, L.-Y.; Hosking, F.; et al. Recurrent Coding Sequence Variation Explains Only a Small Fraction of the Genetic Architecture of Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16286.

- Wang, Y.; McKay, J.D.; Rafnar, T.; Wang, Z.; Timofeeva, M.N.; Broderick, P.; Zong, X.; Laplana, M.; Wei, Y.; Han, Y.; et al. Rare variants of large effect in BRCA2 and CHEK2 affect risk of lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 736–741.

- Michailidou, K.; The Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Collaboration; Hall, P.; Gonzalez-Neira, A.; Ghoussaini, M.; Dennis, J.; Milne, R.L.; Schmidt, M.; Chang-Claude, J.; Bojesen, S.E.; et al. Large-scale genotyping identifies 41 new loci associated with breast cancer risk. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 353–361.

- Stacey, S.N.; Sulem, P.; Jonasdottir, A.; Masson, G.; Gudmundsson, J.; Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Magnusson, O.T.; Gudjonsson, S.A.; Sigurgeirsson, B.; Thorisdottir, K.; et al. A germline variant in the TP53 polyadenylation signal confers cancer susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 1098–1103.

- Enciso-Mora, V.; Hosking, F.J.; Di Stefano, A.L.; Zelenika, D.; Shete, S.; Broderick, P.; Idbaih, A.; Delattre, J.-Y.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Marie, Y.; et al. Low penetrance susceptibility to glioma is caused by the TP53 variant rs. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2178–2185.

- Tian, J.; Chen, C.; Rao, M.; Zhang, M.; Lu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Ying, P.; Li, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Aberrant RNA Splicing Is a Primary Link between Genetic Variation and Pancreatic Cancer Risk. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 2084–2096.

- Li, J.; Zou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Lou, J.; Ke, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; et al. A low-frequency variant in SMAD7 modulates TGF-β signaling and confers risk for colorectal cancer in Chinese population. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 1798–1807.

- Roundtree, I.A.; Evans, M.E.; Pan, T.; He, C. Dynamic RNA Modifications in Gene Expression Regulation. Cell 2017, 169, 1187–1200.

- Frye, M.; Harada, B.T.; Behm, M.; He, C. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science 2018, 361, 1346–1349.

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; He, C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1343–1355.

- Tian, J.; Ying, P.; Ke, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zou, D.; Peng, X.; Yang, N.; Wang, X.; et al. ANKLE1N6-Methyladenosine-related variant is associated with colorectal cancer risk by maintaining the genomic stability. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 3281–3293.

- Chang, J.; Tian, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, R.; Li, J.; Zhai, K.; Ke, J.; Lou, J.; Chen, W.; Zhu, B.; et al. A Rare Missense Variant in TCF7L2 Associates with Colorectal Cancer Risk by Interacting with a GWAS-Identified Regulatory Variant in the MYC Enhancer. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 5164–5172.

- Sud, A.; Kinnersley, B.; Houlston, R. Genome-wide association studies of cancer: Current insights and future perspectives. Nat. Cancer 2017, 17, 692–704.

- Maurano, M.T.; Humbert, R.; Rynes, E.; Thurman, R.E.; Haugen, E.; Wang, H.; Reynolds, A.P.; Sandstrom, R.; Qu, H.; Brody, J.; et al. Systematic Localization of Common Disease-Associated Variation in Regulatory DNA. Science 2012, 337, 1190–1195.

- Wei, G.-H.; Liu, D.-P.; Liang, C.-C. Charting gene regulatory networks: Strategies, challenges and perspectives. Biochem. J. 2004, 381, 1–12.

- Wei, G.H.; Liu, D.P.; Liang, C.C. Chromatin domain boundaries: Insulators and beyond. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 292–300.

- Law, P.J.; The PRACTICAL consortium; Timofeeva, M.; Fernandez-Rozadilla, C.; Broderick, P.; Studd, J.; Fernandez-Tajes, J.; Farrington, S.; Svinti, V.; Palles, C.; et al. Association analyses identify 31 new risk loci for colorectal cancer susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2154.

- Haberle, V.; Stark, A. Eukaryotic core promoters and the functional basis of transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 621–637.

- Wu, S.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sun, H.; Lu, R.; Gao, N.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Aschner, M.; Chen, R. DR4 mediates the progression, invasion, metastasis and survival of colorectal cancer through the Sp1/NF1 switch axis on genomic locus. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 289–297.

- Meng, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, H.; Lu, R.; Gao, N.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Tang, B.; et al. MPO Promoter Polymorphism rs2333227 Enhances Malignant Phenotypes of Colorectal Cancer by Altering the Binding Affinity of AP-2α. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2760–2769.

- Lou, H.; Yeager, M.; Li, H.; Bosquet, J.G.; Hayes, R.B.; Orr, N.; Yu, K.; Hutchinson, A.; Jacobs, K.B.; Kraft, P.; et al. Fine mapping and functional analysis of a common variant in MSMB on chromosome 10q11.2 associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7933–7938.

- Hua, J.T.; Ahmed, M.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Soares, F.; Lu, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; et al. Risk SNP-Mediated Promoter-Enhancer Switching Drives Prostate Cancer through lncRNA PCAT. Cell 2018, 174, 564–575.

- Bojesen, S.E.; Pooley, K.A.; Johnatty, S.E.; Beesley, J.; Michailidou, K.; Tyrer, J.P.; Edwards, S.L.; Pickett, H.A.; Shen, H.C.; Smart, C.E.; et al. Multiple independent variants at the TERT locus are associated with telomere length and risks of breast and ovarian cancer. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 371–384.

- Michailidou, K.; Lindstrom, S.; Dennis, J.; Beesley, J.; Hui, S.; Kar, S.; Lemacon, A.; Soucy, P.; Glubb, D.; Rostamianfar, A.; et al. Association analysis identifies 65 new breast cancer risk loci. Nature 2017, 551, 92–94.

- Noncoding Genetic Variation in GATA3 Increases Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Risk through Local and Global Changes in Chromatin Conformation|Nature Genetics. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41588-021-00993-x (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Williamson, I.; Hill, R.E.; Bickmore, W.A. Enhancers: From Developmental Genetics to the Genetics of Common Human Disease. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 17–19.

- Li, G.; Ruan, X.; Auerbach, R.K.; Sandhu, K.S.; Zheng, M.; Wang, P.; Poh, H.M.; Goh, Y.; Lim, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Extensive Promoter-Centered Chromatin Interactions Provide a Topological Basis for Transcription Regulation. Cell 2012, 148, 84–98.

- Sur, I.; Taipale, I.S.J. The role of enhancers in cancer. Nat. Cancer 2016, 16, 483–493.

- Yan, J.; Chen, S.-A.A.; Local, A.; Liu, T.; Qiu, Y.; Dorighi, K.M.; Preissl, S.; Rivera, C.M.; Wang, C.; Ye, Z.; et al. Histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation modulates long-range chromatin interactions at enhancers. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 204–220.

- Corradin, O.; Scacheri, P.C. Enhancer variants: Evaluating functions in common disease. Genome Med. 2014, 6, 85.

- Ward, L.D.; Kellis, M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 1095–1106.

- Michailidou, K.; Beesley, J.; Lindstrom, S.; Canisius, S.; Dennis, J.; Lush, M.J.; Maranian, M.J.; Bolla, M.K.; Wang, Q.; Shah, M.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 373–380.

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wu, X.; Shan, L.; Pei, F.; et al. SNP rs4971059 predisposes to breast carcinogenesis and chemoresistance via TRIM46-mediated HDAC1 degradation. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e107974.

- Yang, H.; Ting, X.; Geng, Y.-H.; Xie, Y.; Nierenberg, J.L.; Huo, Y.-F.; Zhou, Y.-T.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Y.-Q.; Yu, X.-Y.; et al. The risk variant rs11836367 contributes to breast cancer onset and metastasis by attenuating Wnt signaling via regulating NTN4 expression. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn3509.

- Tian, P.; Zhong, M.; Wei, G.-H. Mechanistic insights into genetic susceptibility to prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021, 522, 155–163.

- Huang, Q.; Whitington, T.; Gao, P.; Lindberg, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Väisänen, M.-R.; Szulkin, R.; Annala, M.; Yan, J.; et al. A prostate cancer susceptibility allele at 6q22 increases RFX6 expression by modulating HOXB13 chromatin binding. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 126–135.

- Gao, P.; Xia, J.-H.; Sipeky, C.; Dong, X.-M.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cruz, S.P.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J.; et al. Biology and Clinical Implications of the 19q13 Aggressive Prostate Cancer Susceptibility Locus. Cell 2018, 174, 576–589.

- Zheng, Y.; Lei, T.; Jin, G.; Guo, H.; Zhang, N.; Chai, J.; Xie, M.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, J.; et al. LncPSCA in the 8q24.3 risk locus drives gastric cancer through destabilizing DDX. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e52707.

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk Variant Modulates lncRNA HLA-DQB1-AS1 Expression via a Long-Range Enhancer–Promoter Interaction|Carcinogenesis|Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/carcin/article/42/11/1347/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Schödel, J.; Bardella, C.; Sciesielski, L.; Brown, J.M.; Pugh, C.; Buckle, V.; Tomlinson, I.P.; Ratcliffe, P.; Mole, D.R. Common genetic variants at the 11q13.3 renal cancer susceptibility locus influence binding of HIF to an enhancer of cyclin D1 expression. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 420–425.

- Yu, C.-Y.; Han, J.-X.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, P.; Shen, C.; Guo, F.; Tang, J.; Yan, T.; Tian, X.; Zhu, X.; et al. A 16q22.1 variant confers susceptibility to colorectal cancer as a distal regulator of ZFP. Oncogene 2020, 39, 1347–1360.

- Tian, J.; Chang, J.; Gong, J.; Lou, J.; Fu, M.; Li, J.; Ke, J.; Zhu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Systematic Functional Interrogation of Genes in GWAS Loci Identified ATF1 as a Key Driver in Colorectal Cancer Modulated by a Promoter-Enhancer Interaction. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 105, 29–47.

- Tian, J.; Lou, J.; Cai, Y.; Rao, M.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zou, D.; Peng, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; et al. Risk SNP-Mediated Enhancer–Promoter Interaction Drives Colorectal Cancer through Both FADS2 and AP002754. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1804–1818.

- Capturing Chromosome Conformation|Science. Available online: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.1067799?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Tolhuis, B.; Palstra, R.-J.; Splinter, E.; Grosveld, F.; de Laat, W. Looping and Interaction between Hypersensitive Sites in the Active β-globin Locus. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 1453–1465.

- Giambartolomei, C.; Seo, J.-H.; Schwarz, T.; Freund, M.K.; Johnson, R.D.; Spisak, S.; Baca, S.C.; Gusev, A.; Mancuso, N.; Pasaniuc, B.; et al. H3K27ac HiChIP in prostate cell lines identifies risk genes for prostate cancer susceptibility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 2284–2300.

- Zhu, Y.; Gujar, A.D.; Wong, C.-H.; Tjong, H.; Ngan, C.Y.; Gong, L.; Chen, Y.-A.; Kim, H.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; et al. Oncogenic extrachromosomal DNA functions as mobile enhancers to globally amplify chromosomal transcription. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 694–707.

- Zheng, H.; Xie, W. The role of 3D genome organization in development and cell differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 535–550.

- Gorkin, D.U.; Leung, D.; Ren, B. The 3D Genome in Transcriptional Regulation and Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 762–775.

- He, H.; Li, W.; Liyanarachchi, S.; Srinivas, M.; Wang, Y.; Akagi, K.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, Q.; Jin, V.; et al. Multiple functional variants in long-range enhancer elements contribute to the risk of SNP rs965513 in thyroid cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6128–6133.

- Zhang, X.; Cowper-Sal·lari, R.; Bailey, S.D.; Moore, J.H.; Lupien, M. Integrative functional genomics identifies an enhancer looping to the SOX9 gene disrupted by the 17q24.3 prostate cancer risk locus. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1437–1446.

- Ling, J.Q.; Li, T.; Hu, J.F.; Vu, T.H.; Chen, H.L.; Qiu, X.W.; Cherry, A.M.; Hoffman, A.R. CTCF Mediates Interchromosomal Colocalization Between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science 2006, 312, 269–272.

- Insulators: Exploiting Transcriptional and Epigenetic Mechanisms|Nature Reviews Genetics. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrg (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Yusufzai, T.M.; Tagami, H.; Nakatani, Y.; Felsenfeld, G. CTCF Tethers an Insulator to Subnuclear Sites, Suggesting Shared Insulator Mechanisms across Species. Mol. Cell 2004, 13, 291–298.

- Ahmed, M.; Soares, F.; Xia, J.-H.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, H.; Su, P.; Tian, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Wang, M.; et al. CRISPRi screens reveal a DNA methylation-mediated 3D genome dependent causal mechanism in prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1781.

- Statkiewicz, M.; Maryan, N.; Kulecka, M.; Kuklinska, U.; Ostrowski, J.; Mikula, M.; Czyżowska, A.; Barbasz, A. Functional analyses of a low-penetrance risk variant rs6702619/1p21.2 associating with colorectal cancer in Polish population. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2019, 66, 305–313.

- Claussnitzer, M.; Cho, J.H.; Collins, R.; Cox, N.J.; Dermitzakis, E.T.; Hurles, M.E.; Kathiresan, S.; Kenny, E.E.; Lindgren, C.M.; MacArthur, D.G.; et al. A brief history of human disease genetics. Nature 2020, 577, 179–189.

- Rahman, M.A.; Krainer, A.R.; Abdel-Wahab, O. SnapShot: Splicing Alterations in Cancer. Cell 2020, 180, 208–208.e1.

- He, L.; Hannon, G.J. MicroRNAs: Small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004, 5, 522–531.

- Esquela-Kerscher, A.; Slack, F. Oncomirs—MicroRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat. Cancer 2006, 6, 259–269.

- Hoffman, A.E.; Zheng, T.; Yi, C.; Leaderer, D.; Weidhaas, J.; Slack, F.; Zhang, Y.; Paranjape, T.; Zhu, Y. microRNA miR-196a-2 and Breast Cancer: A Genetic and Epigenetic Association Study and Functional Analysis. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 5970–5977.

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, S.; Qin, N.; Du, J.; Jin, G.; Hu, Z.; Ma, H.; Shen, H.; et al. Evaluation of CpG-SNPs in miRNA promoters and risk of breast cancer. Gene 2018, 651, 1–8.

- Gao, F.; Xiong, X.; Pan, W.; Yang, X.; Zhou, C.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, L.; Yang, M. A Regulatory MDM4 Genetic Variant Locating in the Binding Sequence of Multiple MicroRNAs Contributes to Susceptibility of Small Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135647.

- Wu, X.-M.; Yang, H.-G.; Zheng, B.-A.; Cao, H.-F.; Hu, Z.-M.; Wu, W.-D. Functional Genetic Variations at the microRNA Binding-Site in the CD44 Gene Are Associated with Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Chinese Populations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127557.

- Ke, J.; Tian, J.; Li, J.; Gong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, R.; Chang, J.; Gong, J. Identification of a Functional Polymorphism Affecting Microrna Binding in the Susceptibility Locus 1q25.3 for Colorectal Cancer. Wiley Online Library, 2021. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi.org/10.1002/mc.22649 (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Shen, C.; Yan, T.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.-C.; Zhu, X.; Tian, X.; Fang, J.-Y.; Chen, H.; Hong, J. Variant of SNP rs1317082 at CCSlnc362 (RP11-362K14.5) creates a binding site for miR-4658 and diminishes the susceptibility to CRC. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1177.

- Feng, T.; Feng, N.; Zhu, T.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhou, B.; Yu, H.; Zheng, M.; et al. A SNP-mediated lncRNA (LOC146880) and microRNA (miR-539-5p) interaction and its potential impact on the NSCLC risk. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 157.

- Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Du, B.; Li, W.; Yu, G.; Li, L.; Zhou, L.; Gu, X.; Song, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. SNP-mediated lncRNA-ENTPD3-AS1 upregulation suppresses renal cell carcinoma via miR-155/HIF-1α signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 672.

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Yang, G.; Peng, S.; Mi, W.; Yin, X.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Q.; et al. SNP rs12982687 affects binding capacity of lncRNA UCA1 with miR-873-5p: Involvement in smoking-triggered colorectal cancer progression. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 37.

- Hou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Tian, T.; Sun, X.; Chen, M.; Xu, W.; Lu, M. Risk SNP-mediated LINC01614 upregulation drives head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 2022, 61, 797–811.