Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Glial–neuronal mitochondrial transfer is mediated via a number of active processes including the release of extracellular vesicles, the formation of tunnelling nanotubes, and potentially other mechanisms.

- mitochondria

- brain

- neuron

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been observed in a wide range of brain states and pathologies, including normal brain aging, brain injury, and disease [1]. Often depicted as the powerhouses of the cell, mitochondria are not only the main generators of energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and glycolysis, but they are also involved in other processes such as calcium homeostasis and apoptosis [2,3]. The term mitochondrial dysfunction encompasses a range of mitochondrial deficits, ranging from bioenergetic impairment, oxidative stress, mitophagy dysfunction, and altered mitochondrial dynamics. As one of the most highly energy-demanding organs in the body [4], the brain is particularly susceptible to mitochondrial impairments, and research has shown that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of brain disorders [1,5,6,7,8]. As a result, a wide range of therapeutics targeting mitochondrial dysfunction in the brain have been tested, including pharmacologic approaches (neuroactive steroids, antioxidants, phenylpropanoids) [9,10,11,12,13,14] and lifestyle interventions (diet, exercise) [3,15,16]. However, the multifaceted and sometimes opposing modes of mitochondrial dysfunction in disease pathology render it difficult to target mitochondrial dysfunction as a whole.

Recently, a novel form of cell-to-cell signalling has been identified in the form of intercellular mitochondrial transfer. This process involves the active transfer of whole mitochondria out of the donor cells via nanotubes, extracellular vesicles, or other methods, where they are internalised by recipient cells and either incorporated into the mitochondrial network or further processed for degradation [17]. This ability to exchange mitochondria has been shown to exert a range of beneficial effects on mitochondrial function in recipient cells, such as increasing ATP levels, restoring mitochondrial membrane potential, and normalizing neuronal calcium dynamics [18,19,20].

Glia, consisting of astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes, perform a wide range of specialist functions in the brain, including removing pathogens and promoting neurorecovery following injury or disease. In addition, glia demonstrate a number of unique properties that make them uniquely positioned to participate in intercellular mitochondrial transfer in the brain. For instance, glia possess the capability to react rapidly to changes in neuronal function, whether by modulating physical contact, regulating neurotransmission, participating in synaptic pruning, and providing metabolic support [21,22]. Further, glia uniquely respond to inflammatory events in the brain by undergoing immune activation and mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming [23], a process which has been shown to increase intercellular mitochondrial transfer [24,25,26]. Intriguingly, glia appear to be more resistant to injury and stress-induced insults in the brain compared to neurons. For instance, whereas treatment with the chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin reduced neuronal survival and impaired mitochondrial function in neurons, no effect on these output measures was observed in astrocytes treated with equivalent doses [18]. Furthermore, astrocytes are more resistant to ischemic injury in vitro [27,28] and show increased survival in animal models of stroke [29]. At the molecular level, DNA-seq data demonstrated that astrocytes have higher concentrations of mitochondrial polymerase gamma (polγ) compared to neurons, which is critically involved in mitochondrial replication, mutagenesis, and repair of mitochondrial DNA [18,30]. Taken together, these findings suggest that glia exhibit greater resilience to injury and stress compared to neurons, and their ability to maintain a healthy pool of mitochondria may underlie this ability.

2. Structural Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Transfer

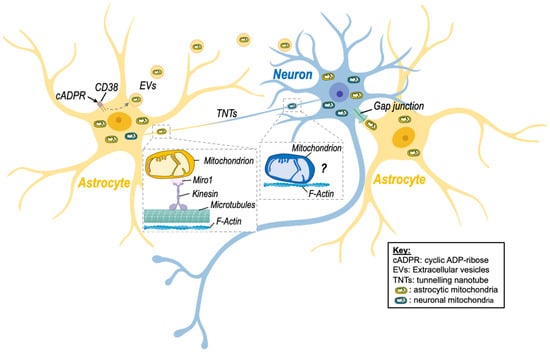

Glial–neuronal mitochondrial transfer is mediated via a number of active processes including the release of extracellular vesicles, the formation of tunnelling nanotubes, and potentially other mechanisms (Figure 1, Table 1). These processes are discussed in detail below:

Figure 1. Intercellular mitochondrial transfer between neurons and astrocytes. Evidence of mitochondrial transfer between neurons and astrocytes has been described, and different processes have been highlighted. Namely, activation of CD38 (cluster of differentiation 38) by cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) induced the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs)-containing mitochondria by astrocytes in a model of stroke, improving neuronal viability. Transfer of mitochondria via tunnelling nanotubes (TNTs) has also been shown. This mode of transfer seems to rely on components of the cytoskeleton (microtubules and F-actin) as well as on the mitochondrial Rho-GTPase-1 protein (Miro-1) and its connection with kinesin for mitochondrial transport. Although transfer of neuronal mitochondria via TNTs is depicted on the figure, there is no clear evidence that mitochondria can be transferred from neurons to astrocytes via this route. Transfer of mitochondria between neuronal cells might involve microtubule-independent mechanism that remain to be identified. Nevertheless, transfer of astrocytic mitochondria to neurons via TNTs has been described. Other processes involving gap junctions may also be involved but still need to be studied in more detail in the brain. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 7 November 2022).

2.1. Extracellular Vesicles

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are bilayer membranous structures that are secreted into the extracellular space. There are two main types of EVs: exosomes and microvesicles. Microvesicles are distinguished from exosomes based on their larger size (typically 0.1–1 μm in diameter), whereas exosomes are much smaller (30–150 nm in diameter) [38]. Astrocytes have been shown to shed EVs containing functional mitochondria ranging from 300 nm up to 8 μm in diameter [20,39]. Similarly, microglia release EVs containing mitochondria into the extracellular space, where they are internalised by astrocytes [35]. It should be noted that EVs containing mitochondria are differentiated from previously identified EV subtypes such as mitovesicles [40] and mitochondria-derived vesicles (MDVs) [41], which are small vesicles that transport mitochondrial-derived cargo but lack several mitochondrial structures such as cristae, mitochondrial ribosomes, and proteins found in mitochondria, such as Tomm20 [40].

2.2. Tunneling Nanotubes

Tunnelling nanotubes (TNTs) were first described in 2004 by Rustom and colleagues [42], who identified membranous channels comprised of F-actin that connect two or more cells and are involved in cell-to-cell communication [43]. TNTs were shown to transfer different organelles, including mitochondria, from one cell to another but also other cargo, including proteins (e.g., α-synuclein) and nucleotides [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Intercellular mitochondrial transfer via TNTs has been observed in astrocytes, microglia, and neurons. For instance, microglia have been shown to form a network of F-actin-positive intercellular membrane projections with neighbouring microglia that contain mitochondria [44]. TNT formation has also been observed between astrocytes and adjacent neurons in rat primary astrocyte and neuronal cells [33,45,46,47]. The direction of mitochondrial transfer between cells via TNTs is not fully understood; however, there is evidence to suggest that TNTs are formed in response to stress. For instance, exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) increased TNT formation between astrocytes in vitro [47]. Further, Wang and colleagues [45] reported that in astrocyte–neuron co-culture, the cells exposed to stressful stimuli, such as H2O2 or serum deprivation, develop TNTs towards the unstressed cells but not vice versa. Other studies have identified the small calcium-binding protein S100A4 and its putative receptor RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end product) as guidance molecules that mediate the growth and direction of TNTs Wang [45]. However, further studies on the mechanistic pathway regulating TNT formation and directionality are needed. Table 1 summarizes findings of studies investigating the effects of mitochondria transfer via TNTs in different brain disease models and highlight the positive effect of this transfer [19,33,36,44,45,48,49,50].

Of note, Sartori-Rupp and colleagues found that mitochondria can be transported between neuronal cells via individual TNTs composed of a single, continuous bundle of parallel actin filaments [51]. This suggests that mitochondria directly bind to actin filaments and are transported via a microtubule-independent mechanism that remains to identified.

2.3. Other Mechanisms

Although most evidence to date suggests that glial–neuronal mitochondrial transfer occurs via EVs or TNTs, a number of other intercellular transfer mechanisms have been proposed, including cell fusion and gap junctions [52]. Gap junctions are plasma membrane channels composed of connexins that have been shown to transfer small molecules [53], and more recently, whole mitochondria [54] between cells. Li and colleagues [55] observed mitochondrial transfer from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells to motor neurons via gap junctions, and gap junction connexin32 is expressed in neurons. However, whether glia cells are capable of transferring mitochondria via gap junction has not yet been investigated. Cell fusion involves the direct fusion of two cellular membranes, which would theoretically allow for the transfer of cytoplasmic molecules, including mitochondria. However no direct evidence of cell fusion mediated mitochondrial transfer in glia or neurons has been observed. Further studies are needed to investigate whether glial–neuronal mitochondrial transfer can occur via gap junctions and cell fusion.

Table 1. Mechanisms of Mitochondria Transfer in the Brain.

| Method of Transfer | Cell Type | Disease Model/Stressor | Effects of Mito Transfer | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Recipient | Donor | Recipient | |||

| EVs | Neural stem cells | BMDM | LPS | N/A | -Increased mitochondrial fusion | [56] |

| -Increased cellular respiration | ||||||

| -Reduced inflammatory gene profiles | ||||||

| EVs | Primary human | N/A | ATP released from neighbouring cells | N/A | N/A | [39] |

| Astrocytes | ||||||

| EVs | Primary rat astrocytes | Primary rat neurons | Oxygen-glucose deprivation | N/A | -Increase ATP levels | [20] |

| -Increased cell viability | ||||||

| TNTs | PC12 cells | PC12 cells | UV light | N/A | -Decreased apoptosis | [48] |

| TNTs | MMSC | Primary astrocytes | Oxygen-glucose deprivation | -Increased transfer | -Restored bioenergetics | [49] |

| and | -Increased proliferation | |||||

| PC12 cells | ||||||

| TNTs | MSC | Neural stem cells | Cisplatin | N/A | -Decreased apoptosis | [50] |

| -Increased MMP | ||||||

| TNTs | Primary mouse astrocytes | Primary mouse neurons | Compressed nitrogen–oxygen mixed gas | N/A | -Increased dendrite length | [19] |

| -Increased transcription of mitochondrial synthesis-related genes | ||||||

| TNTs | Primary mouse microglia | Primary mouse microglia | α-syn | N/A | -Decreased ROS levels | [44] |

| -Decreased apoptotic signalling | ||||||

| TNTs | Primary rat astrocytes | Primary rat astrocytes and neurons | H2O2 or serum depletion | N/A | [45] | |

| TNTs | primary mouse neurons | primary mouse astrocytes | 5xFAD | N/A | -Increased transmitophagy | [33] |

| TNTs | Glioblastoma stem-like cells | Glioblastoma stem-like cells | Irradiation | C1: no effect | N/A | [36] |

| C2: increased transfer | ||||||

Abbreviations: EV, extracellular vesicle; TNT, tunnelling nanotube; BMDM, bone-marrow-derived macrophage; N/A, not applicable.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells11223603

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!