You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Anthocyanins (ACNs) are polyphenolic, water-soluble pigments, and phytochemicals, which in recent years, have garnered the interest of consumers, researchers, and industries for their various potential preventative and/or therapeutic health benefits and applications in the food industry. ACN-based processed foods have emerged as functional foods with significant therapeutic potential against various health conditions.

- anthocyanins

- delivery systems

- stability

- encapsulation

- functional foods

1. Introduction

Anthocyanins (ACNs) are an important class of over 700 polyphenolic, water-soluble natural pigments within the flavonoid family, and characterize various colors, including red, purple, and blue, in a wide range of vegetables, fruits, flowers, and seeds [1,2]. ACNs have demonstrated significant bioactive attributes, and health-promoting benefits, such as antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and anti-neurodegenerative properties, as well as preventative effects against diabetes and ocular diseases, and improvement of vision health [3]. Furthermore, the ACNs isolated from various fruit berries have exhibited the potential to boost cognitive brain function and prevent age-related oxidative damage [4]. These natural pigments also exhibit good potential for various food-related applications. However, a major limitation regarding the use of ACNs for such applications is their degradation owing to sensitivity to various process-associated factors, such as temperature, light, pH, oxygen, co-pigmentation, enzymes, ascorbic acid, and sulfites [5].

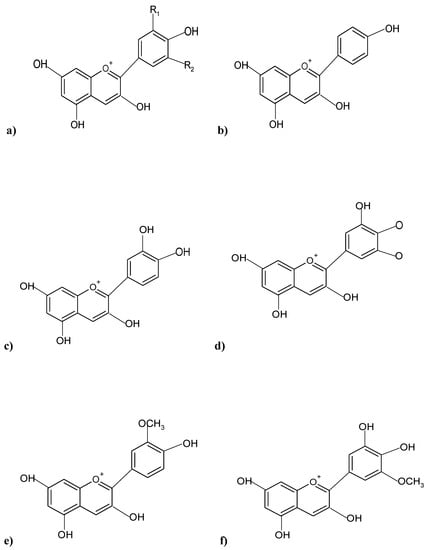

The structure of ACNs generally comprises a single glucoside unit, although various ACNs contain multiple glucoside unit attachments in their structure (Figure 1), occurring as simple sugars, or oligosaccharide side chains, in a characteristic tricyclic (C6-C3-C6) skeleton pattern, and, therefore, can be termed anthocyanidin glycosides [6]. The polar hydroxyl group [OH] present in ACNs facilitates the ACN molecules to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules [7]. The type of color imparted by an ACN, and its intensity is dictated by the number of OH and methoxyl (O-CH3) groups present in the ACN structure, whereby a greater number of OH groups characterize a bluish shade, while more O-CH3 groups impart reddish hues [8]. All higher plants have ACNs in their various tissues, and the most widespread, naturally occurring ACNs are based on six aglycones: cyanidin (50%), pelargonidin (12%), petunidin (7%), delphinidin (12%), peonidin (12%), and malvidin (7%), differing only in terms of B-ring substitution patterns (Figure 1) [9].

Figure 1. Chemical structures of predominant ACNs pigments present in various plants; (a) Basic structure of an ACN; (b) Pelargonidin; (c) Cyanidin; (d) Delphinidin; (e) Peonidin; (f) Petunidin.

ACNs present in fruits, although highly sensitive to chemical and enzymatic degradation reactions, are highly reactive molecules, with significant chemoprotective activity against various diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, and some cancers [5]. This enhanced chemical reactivity can be attributed to the presence of the specific pyrilium nucleus [C-ring] in their structure [10]. Primary factors that affect the stability of ACNs include copigments, temperature, light, oxygen, pH, enzymes, metal ions, solvents, intramolecular, and intermolecular associations, other reactive compounds, as well as the type, and structure of the ACN pigment [11]. These factors, therefore, are key considerations in terms of applications involving ACNs in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

ACNs are being utilized as natural, water-soluble, Codex Alimentarius-approved food colorants (E163), and dyes for a diverse range of food and beverage products [12,13]. Encapsulated ACNs are also used as fortificants in cereal products (cookies, wafers, biscuits, and tortillas), juices, beverages, and milk products [14,15]. ACNs encapsulated in gelatin/CH electrosprayed microparticles could be used in formulating functional liquid and nutraceutical foods [16]. Additionally, ACNs are regarded as nutraceutical ingredients of considerable therapeutic potential for the development of advanced nutraceuticals and functional foods [4,17]. Furthermore, ACNs have also found applications in the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries, for instance, for the development of health supplements [18,19]. As mentioned already, though the potential of applications is significant, the stability issues associated with ACNs limit their utilization in processing applications [20].

The limitation of ACNs in terms of food applications is directly related to their bioavailability; as they undergo extensive presystemic degradation, and hence, are poorly absorbed [21]. The bioavailability of ACNs is reportedly very low, with recoveries of <1% of the ingested dose of ACNs [22]. Albeit higher recoveries have been reported as well in some in vitro studies, reaching values of 12.4% [23,24]. ACNs are usually assimilated from the stomach and small intestine, although, a considerable proportion can reach the large intestine, where these ACNs are subjected to extensive catabolism, resulting in the formation of various metabolites, for instance, phenolic and propionic acids [22]. ACNs in their glycoside forms have demonstrated superior stability under low pH (1.5–4) conditions in the stomach, allowing for their absorption in the small intestine as intact molecules [25]. ACN aglycones, upon reaching intestinal epithelia, undergo metabolism before entering portal circulation, in two distinct phases, phase I metabolism (oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis reactions), and phase II metabolism (conjugation reactions) [22].

Moreover, in the intestine, ACNs undergo sulfation, methylation, and glucuronidation under the influence of sulfotransferase, catechol-O-methyltransferase, and uridine-5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes [26]. Alternatively, ACNs aglycones may undergo degradation and fragmentation induced by the action of deglycosylation enzymes produced by the colonic microbiota, resulting in the formation of aglycones that undergo further ring-opening, leading to the production of various aldehydes, and benzoic acids, such as vanillic, gallic, protocatechuic, and syringic acids [27]. Consequently, the proportion of phenolic acids increases, while that of ingested ACNs decreases, as they progress further along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The low in vivo bioavailability of ACNs can be attributed to their low permeability, low water solubility, inadequate gastric residence time, and high sensitivity to the GI environment, where they undergo substantial pH-dependent transformations [28]. Therefore, only a small portion of the consumed ACNs is recovered in plasma/urine, and <0.1% is excreted in the intact form [29]. This calls for the development of methods aimed at reducing the degradation of ingested ACNs, and therefore, enhancing their bioavailability [30].

ACNs can be stabilized by embedding them in nanocarrier systems to produce microcapsules, acylating their reactive groups, or forming copigments with other macromolecules [31]. A significant number of research studies have recorded the encapsulation of ACNs using different techniques and encapsulating materials [30,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Encapsulation technology is focused on the entrapment of bioactive compounds and the formation of one stable form, either in a solid or liquid state, which can significantly enhance ACN stability, bioaccessibility, and bioavailability [38]. One of the most commonly used encapsulation materials for ACNs, among others such as chitosan and Gum Arabic, are cyclodextrins (CDs), whereby the apolar guest molecules (for instance, amphiphilic ACN aglycones) can be trapped within the torus-shaped apolar cavity of CDs through electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces (utilizing techniques such as molecular inclusion or host-guest complexation) [39]. CDs owing to their hydrophobic interior, and hydrophilic exterior, allow them to form complexes with a wide range of organic components, thereby also permitting the selectivity of the organic compounds to be encapsulated, which can be attributed to the adaptable nature of the hydrophobic cavity of CDs, as well as its size [40]. Encapsulating bioactives such as ACNs in CDs offers significant advantages, including enhanced solubility, improved permeability across intestinal membranes, as well as improved bioavailability of the encapsulated materials [39].

2. Bio-Based Materials Used for the Stabilization of ACNs

2.1. Pectin

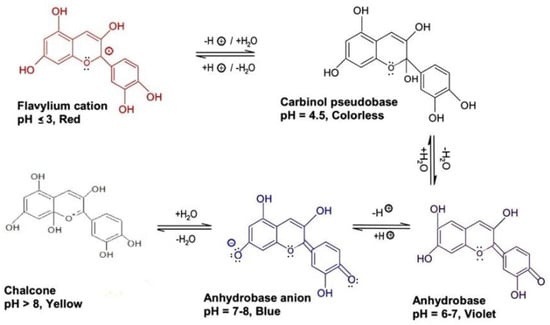

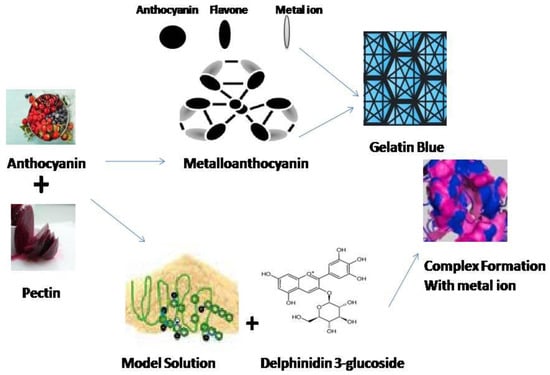

Pectin (PC), a polysaccharide polymer, is a viable solution for the stabilization of ACNs by way of the formation of non-covalent complexes [47]. ACN metal chelate complexes solubilized in PC prevented the precipitation of ACNs in aqueous environments, making them a potential candidate for beverage-related applications [48]. The most probable mechanisms responsible for ACN-PC binding appear to be ionic interactions between positively-charged ACN flavylium cations and free pectic carboxyl groups, and ACNs aromatic stacking on bound ACNs [49]. The binding exhibits an increasing trend, as pH becomes more acidic, given that flavylium cation is more dominant and prevalent in the pH range of 1–3, with the converse increase in pH values causing a decrease in the concentration of flavylium cations [50]. This trend can be seen in Figure 2, where the effect of pH on the color stability of ACNs can be observed. PCs isolated from sugar beet, apple, and citrus improved the stability characteristics of ACN extracts from blackcurrant, and strawberry, making them suitable for food and beverage applications [50].

Figure 2. A pictorial description of the pH effect on ACN color stability; changes in ACN color pigments due to the chemical alteration in nitrogenous compounds under various pH conditions.

Similarly, blueberry PC (chelator-soluble) enhanced the stability attributes of malvidin-3-glucoside (M3G), blueberry extract, and cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) during in vitro GI digestion simulation studies [51]. ACNs with improved bioavailability influence the gut microbiota composition and increase the number of beneficial bacteria, lower inflammation, and alter the glycemic response, and other physiological responses [52].

2.2. Proteins

The interaction of ACNs with protein can improve the overall stability of the ACN-protein complex, as well as its functional, and nutritional properties [53]. ACNs and proteins combine owing to the inherent sensitivity of ACNs to alkaline oxidation, in turn yielding quinones [54], which tend to form strong and fairly stable C-N or C-S covalent bonds by way of the nucleophilic addition of mercaptan and amino groups on the protein side chains [55]. Given that the bioavailability of ACNs in the human body is markedly low [9], combining ACNs with proteins can significantly improve the stability of these compounds, as well as enhance their absorption rates [30].

ACNs from sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) peel were encapsulated with whey protein isolates (WPI) and acacia gums, with an encapsulation efficiency of 70.30 ± 2.20%, and the in vitro digestibility analyses indicated that WPIs protected ACNs against gastric digestion, thereby facilitating their release in the small intestine [56].

2.3. Lipids

Encapsulation of ACNs in emulsion droplets is a viable solution for enhancing their stability, and bioavailability. Studies have reported the encapsulation of ACNs in various types of emulsions, predominantly water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsions [57]. The W/O/W emulsions have different internal and external values of pH, which may slow down pH-induced color changes in the encapsulated ACNs [58]. Phospholipids including lecithin isolated from the soybean, eggs, lecithin, and marine sources, as well as milk phospholipids, also form a major component of the liposome delivery systems [59]. The presence of cholesterol along with phospholipids has also proven significant for the stabilization of ACNs [60].

2.4. Biopolymer Complexes

Natural biopolymeric complexes, in particular, polysaccharides and protein matrices being utilized for the encapsulation of ACNs [61]. The presence of electrostatic interaction-induced supramolecular structures within these macromolecules, their non-hazardous nature, and their generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status render them highly versatile vehicles for encapsulating and delivering ACNs in food-associated applications [62]. Copigmentation intensifies and stabilizes the color of ACNs by protecting the flavylium cation of these pigments from nucleophilic attack [63].

The biopolymers widely reported to be suitable for the copigmentation of ACNs include PC, dextran sulfate, guar gum, gum arabic, and whey proteins [62]. For instance, in a study, gum arabic (0.05–5.0%) significantly improved the color stability of purple carrot ACNs when used for commercial beverage applications, with the highest stability levels occurring at intermediate gum arabic concentrations (1.5%) [64].

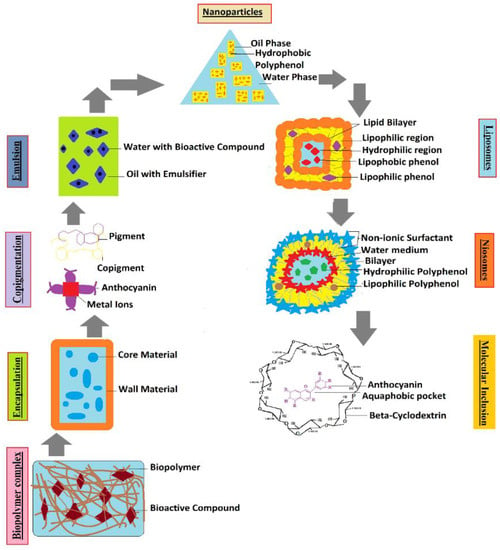

3. ACN Delivery Systems

Different types of colloidal particles can be used as viable delivery systems for ACNs (Figure 3 and Figure 4), including, nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), solid-lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), liposomes, emulsions, and others [65]. In encapsulation, highly sensitive constituents are enclosed within a wall material before delivering inside a system and could be formed by nanoencapsulation (<1 µm) or microencapsulation (1–1000 µm) depending upon the particle size [66]. This significantly improves the stability, water solubility, and bioavailability of bioactive compounds [67] and prevents the enzymatic and chemical degradation of ACNs [68]. However, conventional microencapsulation has not proven effective in the context of stability studies for ACNs, primarily because of their bigger particle size and low encapsulation efficiency [69].

Figure 3. Pictorial representation showing the interaction of polysaccharide-based wall material (pectin) with the ACNs color pigments as encapsulating agents to increase the stability of ACNs.

Figure 4. Formulation of different conventional and advanced delivery systems used for encapsulation of ACN pigments in different biopolymer complexes (carbohydrates, protein, lipids), and wall materials.

Different formulation and storage techniques related to encapsulation are summarized in Table 1. Protein-based delivery systems are frequently used in microencapsulation owing to various favorable attributes, such as cost-effectiveness, porous structure, surface-active nature, and ability to self-assemble, bind water molecules, and form stable, biodegradable hydrogels [70].

Table 1. Methods for encapsulation of anthocyanin using different material and their outcomes.

| Method | Source | Encapsulation Material | Study Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spray drying | Grape juice | Maltodextrin, whey proteins, soybean | 120 days of ACNs stability at 35 °C using soybean with maltodextrin (10% degradation) | [71] |

| Pomegranate powder | Gum arabic and modified starch | Higher ACNs retention (60%) | [72] | |

| Jussara | Starch, inulin, and Maltodextrin | ACNs color maintained together with light stability at 50 °C for 38 days | [73] | |

| Barberry | Gum arabica, Maltodextrin, and gelatin | Microencapsulation efficiency of 92.8% was achieved during the study | [74] | |

| Grape pomace | Maltodextrins | 11 days’ half-life stability of encapsulated ACNs into apple pure matrix at 35 °C | [75] | |

| Jussara | Gum arabica, modified starch, whey proteins, or Soy protein isolate | The use of the two polysaccharides with either one of the proteins resulted in high encapsulation efficiency and ACNs retention | [76] | |

| Purple sweet potato | MC grafted with cinnamic acid | Maltodextrins with cinnamic acid improved ACNs stability over 30 days’ storage time in comparison to maltodextrin or free ACNs | [77] | |

| Blueberry | Whey proteins | Encapsulated blueberry ACNs were more stable than blueberry extract | [78] | |

| Purple maize | Modified, normal, and waxy maize starches | Acetylated starches had superior encapsulating power for ACNs | [79] | |

| Black raspberry juice | Maltodextrin, fenugreek gum, and microcrystalline cellulose | Gum and cellulose increased the overall properties of the powders and ACN concentration | [80] | |

| Roselle extract | Maltodextrin, pectin, gelatin, Carboxy methyl cellulose, whey proteins, carrageenan, and Gum arabica | Pectin showed better retention and release, throughout the storage period | [81] | |

| Blueberry | Maltodextrin and Gum arabica | The use of an ultrasonic nozzle better protected the blueberry bioactive than the conventional nozzle and had similar results for AA and total ACN contents | [82,83] | |

| Jussara pulp | Gelatin, Gum arabica, maltodextrin | Optimization study pointed to 165 °C and 5% of carrier material as the best for ACNs retention. At 40 °C and 75% of relative humidity, ACNs half-life was 14 days when coated with GA | [84] | |

| Saffron anthocyanin | β-glucan and β-cyclodextrin | Higher concentrations of ACNs were protected from adverse stomach conditions by encapsulation | [85] | |

| Roselle extract | β-cyclodextrin, soy protein isolate, gelatin | Increased the thermal stability and encapsulation efficiency by 99% using the composite wall materials of purified roselle extract | [86] | |

| Freeze-drying | Raspberry | Gum arabica and Soy proteins | Increased retention of ACNs by 36% | [30] |

| Milk-Blackberry pulp | Maltodextrin and modified starch | High anthocyanin content and increased antioxidant capacity | [87] | |

| Sour cherry | Soy proteins and whey proteins | SP showed higher encapsulation efficiency and higher anthocyanin content | [88] | |

| Grape extract | Acacia gum and whey proteins | Improved encapsulation efficiency of ACN | [89] | |

| Wine grape pomace | Gum arabica and Maltodextrin | Samples had 91% encapsulation efficiency | [90] | |

| Saffron petal | Cress seed gum, Gum arabica, Maltodextrin | Cress seed gum had the same results for ACNs stability as other conventional wall materials however, lower color constancy | [91] | |

| Cherry juice | Maltodextrin and Gum arabica | ACN retention was 90%, in comparison to liquid juice (11%) | [92] | |

| Electrospraying | Black carrot extract | Gelatin and chitosan | Faster release in the acetic acid medium with greater encapsulation efficiency | [16] |

| Ultrasonication | Anthocyanin | Lecithin | Sustained release and high stability of anthocyanin | [93] |

| Electrospinning | Sour cherry extract | Lactalbumin and gelatin | Increased bioaccessibility and stability of ACNs | [94] |

| Copigmentation | Blueberry | Chondroitin sulfate and kappa carrageenan | Effective protection against degradation at low pH | [95] |

| Anthocyanin | Guar gum | High encapsulation efficiency and high kinetic stability | [57] | |

| Blueberry and Elderberry | Chondroitin and chitosan | Improved chemical stability and stable color of anthocyanin | [96] | |

| ACNs extract | Gum arabica | GA coating increased color stability and half-life of ACNs at high temperatures | [97] | |

| Bilberry | Dextran sulfate | During storage in dark conditions at 4 °C, ACN content decreased by 12% as compared to extract (35%) | [98] | |

| Supercritical CO2 | Bilberry | Soy lecithin | Higher stability and encapsulation efficiency | [99] |

| Microwave | Roselle and Red Cabbage | Maltodextrin | Encapsulated ACNs were able to improve margarine stability against phase separation and oxidation | [100] |

| Extrusion | Haskap berries | Calcium-alginate | The increased residence time of microparticle gels in the stomach suggests a more controlled release of ACNs | [101,102] |

| Clitoria ternatea petal flower extract | Alginate and calcium chloride | Thermal stability with inhibition of carbohydrate and lipid digestion | [26] | |

| Evaporation | Cyanidin-3-glycoside extract | N-trimethyl chitosan-coated liposomes | Coating ACNs increase the antioxidant activity in rat’s cornea, with higher transepithelial transport | [103] |

| Gelation | Jussara extract | Alginate, chitosan, whey proteins, gelatin | Alginate hydrogel beads and chitosan showed greater antioxidant capacity [higher protection] as compared to WP and gelatin | [104] |

| Black rice | Maltodextrin, Gum arabica, whey proteins | Whey protein isolates exhibited a greater release of anthocyanin in GIT with enhanced antioxidant activity | [105] | |

| Mulberry | Alginate and chitosan beads | High ACN encapsulation efficiency | [106] | |

| Purple rice bran | Pectin, zein, and whey proteins | Pectin-WP and Pectin-zein-WP capsules have the potential of slowly releasing delivery systems for ACNs | [107] | |

| Blueberry | Chitosan/cellulose Chitosan/sodium tripolyphosphate | Cellulose nanocrystals had better ACN recovery and stability at pH 7 than sodium tripolyphosphate | [108] | |

| Sol-gel technique | Black carrot | Silica (drug delivery system) | Nanoparticles with ACNs were able to inhibit 87.9% of neuroblastoma cells | [109] |

| Coacervation | Black rice | Gelatin-acacia gum and chitosan- Carboxymethylcellulose | Microcapsules can be applied for incorporating ACNs into nutraceuticals for controlled release | [110] |

| Blueberry | Chitosan | Chitosan was able to stabilize ACNs after simulated GI fluid assay and storage | [111] | |

| Purple sweet potato | Konjac glucomannan | Extra chitosan oligosaccharides coat was needed to stabilize microspheres against stomach conditions and to release ACNs in the small intestine [in vitro] | [112] | |

| Inclusion Complexes | Bignay and duhat extract | β-cyclodextrin | Increased encapsulation efficiency and possess enzyme inhibitory properties | [113] |

| Yeast mediated encapsulation | Chokeberry ACNs | Saccharomyces cerevisiae [yeast] | Yeast turned the ACNs efficiency around by 55% | [114] |

These hydrogels, therefore, are not only suitable for encapsulating ACNs, ensuring stability, and controlled release, but also offer opportunities to be used for many food industry applications, such as thickeners (sauces, soups), texturizers (confections), and flavors (slow-release) [115]. Nanoencapsulated complexes comprising CH hydrochloride, carboxymethyl CH, and β-Lg incorporated with ACN extracts also improved their bioavailability and stability [116]. Another novel technique for encapsulation of ACN-rich extracts is by using niosomes, which have emerged as a suitable delivery system for ACNs, owing to the low toxicity and high biocompatibility attributes of these liposomal formulations [117]. Molecular inclusion complexes are another approach to stabilize ACNs, whereby ACNs have been coupled with β-cyclodextrins (β-CDs), resulting in slower GI stabilization, as well as protecting the ACNs from polymerization and hydration reactions [118]. This complexation with CDs increased thermal stability and reduced the degradation of ACNs, thereby protecting them in the difficult GI environment. Furthermore, the utilization of CDs as encapsulation materials for bioactive compounds may lead to enhanced solubility, greater permeability through intestinal membranes, as well as greater bioavailability of the encapsulated compounds [119].

3.1. Nanoparticles

In a study [120], ACN extracts encapsulated in β-Lg nanoparticles exhibited greater antioxidant activity and enhanced retention at various pH ranges: pH 6.8 (mouth), pH 6.9 (simulated gastric), and pH 2 (simulated intestinal), as compared to unencapsulated ACNs. Nanocarriers formulated using CH-PC complexes provided adequate protection against degradation by gastric juice and therefore, facilitated the release of ACNs in the small intestine [121]. Nanocomposites containing amphiphilic peptide C6M1 significantly improved the stability of ACNs against increased pH, elevated temperatures, and metallic ions [120].

Similarly, zein-ACN nanoparticles have been found to exhibit greater encapsulation efficiency and scavenging activity as compared to ACN extracts without nanocrystallization [122]. SLNs made up of solid lipid shells [high melting lipid matrix], also have a better encapsulation efficiency, slow rate of degradation, superior stability, and low cost of production, as compared to nanoemulsions (NEs) [123]. ACNs from red cabbage encapsulated in SLNs prepared by way of diluting the water-in-oil [W/O] microemulsions (MEs) containing ACNs in the aqueous phase exhibited greater stability under GI conditions, as compared to unencapsulated ACNs [69]. However, encapsulating ACNs in SLNs might be challenging owing to their tendency to partition into the aqueous phase during preparation procedures [124].

3.2. Liposomes

Liposomes have demonstrated the potential to protect and stabilize ACNs, ensuring their prolonged presence in the systemic circulation, and therefore, enhanced cellular uptake in the human body [125]. Nanoliposomes, resulting from particle size reduction of conventional liposomes using ultrasound, membrane extrusion, or high-pressure homogenization, in particular, has emerged as an excellent delivery system for ACNs, owing to their amphipathic, non-immunogenic, and non-toxic characteristics, biodegradability, and biocompatibility [69].

3.3. Emulsions

Multiple emulsions, or more colloquially, double emulsions, such as W/O/W emulsions, are garnering increasing interest in the context of encapsulation, enhanced retention, and improved protection of ACNs [126]. Huang and Zhou [127] encapsulated ACNs from black rice extract in a W/O/W emulsion, evaluated the changes in ACN concentration, and release attributes of the multiple emulsion by way of an in vitro simulated digestion study. The study reported a high microencapsulation efficiency of 99.45 ± 0.24%, and that the multiple emulsion-maintained encapsulations even after 2 h of exposure to gastric juice, thereby preventing the release of ACNs in the stomach environment [127].

Likewise, owning a large droplet surface area, and a reduction in particle size have made NEs a proven solution for increasing the functionality of ACNs contained within [128]. Furthermore, NEs provide greater stability against droplet aggregation and gravitational separation owing to their high surface-to-volume ratio, an attribute of critical significance from the perspective of shelf-life enhancement of various food and beverage industry products [129].

3.4. Biopolymer Particles

Biopolymer particles comprise a dense framework, including supramolecular structures formed through electrostatic interactions, which can be used to encapsulate and deliver ACNs in the human body [11]. The properties of the carrier type, or wall material, as well as the various interactions between the polymer system, and bioactive ensure that the release of the core components is initiated at a specific time and location within the human GI system [45].

Among the carrier agents, the most commonly used biopolymers for ACNs encapsulation in recent years include maltodextrins (19.56%), gums (15.22%), milk proteins (13.04%), starches, and their derivatives (>9.78%) [130]. Alginate, the polysaccharide isolated from various brown seaweeds, forms gels [through ionotropic gelation] in the presence of cations (Ca2+, Ba2+, Zn2+) as crosslinkers, making these gels favorable options as delivery systems [131]. Natural polymers, when compared to their synthetic analogs, are highly biocompatible and biodegradable, and can be used for the entrapment of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs [132]. A coacervated complex of CH and PC was used to encapsulate ACNs, with the subsequent in vitro analysis revealing that the bioaccessibility percentage of the coacervated ACNs formulation was markedly higher when compared to both the crude ACNs extract and the purified ACNs crystals [133].

More recently, dietary fibers have gained prominence as biocompatible, biodegradable, relatively less toxic, and cost-effective colon-targeted delivery systems for various natural polyphenols with therapeutic potential [134]. The various advantages imparted by these polymers include maintenance of the structural integrity of delivery systems, thereby shielding polyphenols from the harsh environmental conditions in the GI tract, facilitating the colonic microbe-mediated polyphenol biotransformation, strengthening dietary fiber-polyphenol interlinkages, improved colon-associated mucoadhesion, and resultant enhanced payload delivery, and synergistic prebiotic effects [135,136] reported that hydrogels prepared using glucomannan and xanthan gums isolated from konjac [Amorphophallus konjac] for encapsulation of ACNs offered superior protection against pH variations in the GI tract.

3.5. Copigmentation

Copigmentation stabilizes ACNs by way of the formation of a non-covalent molecular complex with a colorless organic or inorganic compound [63]. The ‘sandwich’ complex that results, therefore, renders greater protection to the flavylium chromophore against the water molecule-induced nucleophilic substitution, thereby preventing the degradation of ACNs to colorless chalcone and hemiketal forms [137]. PC-induced copigmentation of European bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) ACN extracts extended stability to both ACNs and the resulting multiple emulsions [62]. Furthermore, ACNs copigmented with PC or chondroitin sulfate (CS) (negative charge) combine with CH (positive charge), manifesting in the formation of polyelectrolyte complexes [PECs] that can be utilized as delivery systems and have been shown to enhance the biological function of ACNs [138].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app122312347

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!