Jujutsu (/dʒuːˈdʒuːtsuː/ joo-JOOT-soo; Japanese: 柔術, jūjutsu listen (help·info)), also known as Jujitsu or Jiu-Jitsu, is a Japanese martial art and a method of close combat for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses either a short weapon or none.

- martial art

- jujutsu

- jujutsu

1. Characteristics

"Jū" can be translated to mean "gentle, soft, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding". "Jutsu" can be translated to mean "art" or "technique" and represents manipulating the opponent's force against themselves rather than confronting it with one's own force.[1] Jujutsu developed to combat the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no weapon, or only a short weapon.[2] Because striking against an armored opponent proved ineffective, practitioners learned that the most efficient methods for neutralizing an enemy took the form of pins, joint locks, and throws. These techniques were developed around the principle of using an attacker's energy against him, rather than directly opposing it.[3]

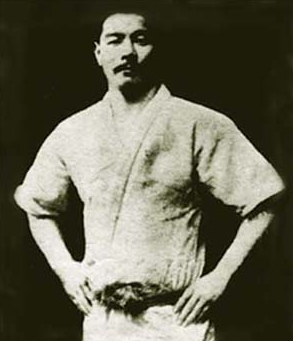

There are many variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches. Jujutsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree (i.e. throwing, trapping, joint locks, holds, gouging, biting, disengagements, striking, and kicking). In addition to jujutsu, many schools teach the use of weapons. Today, Jujutsu is practiced in both traditional and modern sports forms. Derived sport forms include the Olympic sport and martial art of judo, which was developed by Kanō Jigorō in the late 19th century from several traditional styles of jujutsu, and Brazilian jiu-jitsu, which was derived from earlier (pre–World War II) versions of Kodokan judo.

2. Etymology

Jujutsu, the current standard spelling, is derived using the Hepburn romanization system. Before the first half of the 20th century, however, Jiu-Jitsu and Ju-Jitsu were preferred, even though the romanization of the second kanji as Jitsu is unfaithful to the standard Japanese pronunciation. Since Japanese martial arts first became widely known of in the West in that time period, these earlier spellings are still common in many places. Ju-Jitsu is still a common spelling in France , Canada , and the United Kingdom while Jiu-Jitsu is most widely used in Germany and Brazil .

Some define jujutsu and similar arts rather narrowly as "unarmed" close combat systems used to defeat or control an enemy who is similarly unarmed. Basic methods of attack include hitting or striking, thrusting or punching, kicking, throwing, pinning or immobilizing, strangling, and joint locking. Great pains were also taken by the bushi (classic warriors) to develop effective methods of defense, including parrying or blocking strikes, thrusts and kicks, receiving throws or joint locking techniques (i.e., falling safely and knowing how to "blend" to neutralize a technique's effect), releasing oneself from an enemy's grasp, and changing or shifting one's position to evade or neutralize an attack. As jujutsu is a collective term, some schools or ryu adopted the principle of ju more than others.

From a broader point of view, based on the curricula of many of the classical Japanese arts themselves, however, these arts may perhaps be more accurately defined as unarmed methods of dealing with an enemy who was armed, together with methods of using minor weapons such as the jutte (truncheon; also called jitter), tantō (knife), or Kaku shi buki (hidden weapons), such as the ryofundo kusari (weighted chain) or the bankokuchoki (a type of knuckle-duster), to defeat both armed or unarmed opponents.

Furthermore, the term jujutsu was also sometimes used to refer to tactics for infighting used with the warrior's major weapons: katana or tachi (sword), yari (spear), naginata (glaive), jō (short staff), and bō (quarterstaff). These close combat methods were an important part of the different martial systems that were developed for use on the battlefield. They can be generally characterized as either Sengoku period (1467–1603) katchu bu Jutsu or yoroi kumiuchi (fighting with weapons or grappling while clad in armor), or Edo period (1603–1867) suhada bu Jutsu (fighting while dressed in the normal street clothing of the period, kimono and hakama).

The Chinese character 柔 (Mandarin: róu; Japanese: jū; Korean: yū) is the same as the first one in 柔道/judo (Mandarin: róudào; Japanese: jūdō; Korean: Yudo). The Chinese character 術 (Mandarin: shù; Japanese: jutsu; Korean: sul) is the same as the second one in 武術 (Mandarin: wǔshù; Japanese: bujutsu; Korean: musul).

3. History

3.1. Origins

Jujutsu first began during the Sengoku period of the Muromachi period combining various Japanese martial arts which were used on the battlefield for close combat in situations where weapons were ineffective. In contrast to the neighbouring nations of China and Okinawa whose martial arts were centered around striking techniques, Japan ese hand-to-hand combat forms focused heavily upon throwing, immobilizing, joint locks and choking as striking techniques were ineffective towards someone wearing armor on the battlefield. The original forms of jujutsu such as Takenouchi-ryū also extensively taught parrying and counterattacking long weapons such as swords or spears via a dagger or other small weapons.

In the early 17th century during the Edo period, jujutsu would continue to evolve due to the strict laws which were imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate to reduce war as influenced by the Chinese social philosophy of Neo-Confucianism which was obtained during Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea and spread throughout Japan via scholars such as Fujiwara Seika.[4] During this new ideology, weapons and armor became unused decorative items, so hand-to-hand combat flourished as a form of self-defense and new techniques were created to adapt to the changing situation of unarmored opponents. This included the development of various striking techniques in jujutsu which expanded upon the limited striking previously found in jujutsu which targeted vital areas above the shoulders such as the eyes, throat, and back of the neck. However towards the 18th century the number of striking techniques was severely reduced as they were considered less effective and exert too much energy; instead striking in jujutsu primarily became used as a way to distract the opponent or to unbalance him in the lead up to a joint lock, strangle or throw.

During the same period the numerous jujutsu schools would challenge each other to duels which became a popular pastime for warriors under a peaceful unified government, from these challenges randori was created to practice without risk of breaking the law and the various styles of each school evolved from combating each other without intention to kill.[5][6]

The term jūjutsu was not coined until the 17th century, after which time it became a blanket term for a wide variety of grappling-related disciplines and techniques. Prior to that time, these skills had names such as "short sword grappling" (小具足腰之廻, kogusoku koshi no mawari), "grappling" (組討 or 組打, kumiuchi), "body art" (体術, taijutsu), "softness" (柔 or 和, yawara), "art of harmony" (和術, wajutsu, yawarajutsu), "catching hand" (捕手, torite), and even the "way of softness" (柔道, jūdō) (as early as 1724, almost two centuries before Kanō Jigorō founded the modern art of Kodokan Judo).[7]

Today, the systems of unarmed combat that were developed and practiced during the Muromachi period (1333–1573) are referred to collectively as Japanese old-style jujutsu (日本古流柔術, Nihon koryū jūjutsu). At this period in history, the systems practiced were not systems of unarmed combat, but rather means for an unarmed or lightly armed warrior to fight a heavily armed and armored enemy on the battlefield. In battle, it was often impossible for a samurai to use his long sword or polearm, and would, therefore, be forced to rely on his short sword, dagger, or bare hands. When fully armored, the effective use of such "minor" weapons necessitated the employment of grappling skills.

Methods of combat (as mentioned above) included striking (kicking and punching), throwing (body throws, joint lock throws, unbalance throws), restraining (pinning, strangling, grappling, wrestling) and weaponry. Defensive tactics included blocking, evading, off-balancing, blending and escaping. Minor weapons such as the tantō (knife), ryofundo kusari (weighted chain), kabuto wari (helmet breaker), and Kaku shi buki (secret or disguised weapons) were almost always included in Sengoku jujutsu.

3.2. Development

In later times, other ko-ryū developed into systems more familiar to the practitioners of Nihon jujutsu commonly seen today. These are correctly classified as Edo jūjutsu (founded during the Edo period): they are generally designed to deal with opponents neither wearing armor nor in a battlefield environment. Most systems of Edo jujutsu include extensive use of atemi waza (vital-striking technique), which would be of little use against an armored opponent on a battlefield. They would, however, be quite valuable in confronting an enemy or opponent during peacetime dressed in normal street attire (referred to as "suhada bujutsu"). Occasionally, inconspicuous weapons such as tantō (daggers) or tessen (iron fans) were included in the curriculum of Edo jūjutsu.

Another seldom-seen historical side is a series of techniques originally included in both Sengoku and Edo jujutsu systems. Referred to as Hojo waza (捕縄術 hojojutsu, Tori Nawa Jutsu, nawa Jutsu, hayanawa and others), it involves the use of a hojo cord, (sometimes the sageo or tasuke) to restrain or strangle an attacker. These techniques have for the most part faded from use in modern times, but Tokyo police units still train in their use and continue to carry a hojo cord in addition to handcuffs. The very old Takenouchi-ryu is one of the better-recognized systems that continue extensive training in hojo waza. Since the establishment of the Meiji period with the abolishment of the Samurai and the wearing of swords, the ancient tradition of Yagyu Shingan Ryu (Sendai and Edo lines) has focused much towards the jujutsu (Yawara) contained in its syllabus.

Many other legitimate Nihon jujutsu Ryu exist but are not considered koryu (ancient traditions). These are called either Gendai Jujutsu or modern jujutsu. Modern jujutsu traditions were founded after or towards the end of the Tokugawa period (1868) when more than 2000 schools (ryū) of jūjutsu existed. Various traditional ryu and ryuha that are commonly thought of as koryu jujutsu are actually gendai jūjutsu. Although modern in formation, very few gendai jujutsu systems have direct historical links to ancient traditions and are incorrectly referred to as traditional martial systems or ryu. Their curriculum reflects an obvious bias towards Edo jūjutsu systems as opposed to the Sengoku jūjutsu systems. The improbability of confronting an armor-clad attacker is the reason for this bias.

Over time, Gendai jujutsu has been embraced by law enforcement officials worldwide and continues to be the foundation for many specialized systems used by police. Perhaps the most famous of these specialized police systems is the Keisatsujutsu (police art) Taiho jutsu (arresting art) system formulated and employed by the Tokyo Police Department.

Jujutsu techniques have been the basis for many military unarmed combat techniques (including British/US/Russian special forces and SO1 police units) for many years. Since the early 1900s, every military service in the world has an unarmed combat course that has been founded on the principal teachings of Jujutsu.[8]

There are many forms of sports jujutsu, the original and most popular being judo, now an Olympic sport. One of the most common is mixed-style competitions, where competitors apply a variety of strikes, throws, and holds to score points. There are also kata competitions, where competitors of the same style perform techniques and are judged on their performance. There are also freestyle competitions, where competitors take turns attacking each other, and the defender is judged on performance. Another more recent form of competition growing much more popular in Europe is the Random Attack form of competition, which is similar to Randori but more formalized.

4. Description

The word Jujutsu can be broken down into two parts. "Ju" is a concept. The idea behind this meaning of Ju is "to be gentle", "to give way", "to yield", "to blend", "to move out of harm's way". "Jutsu" is the principle or "the action" part of Ju-Jutsu. In Japanese this word means science or art.[9]

Japanese jujutsu systems typically emphasize more on throwing, pinning, and joint-locking techniques as compared with martial arts such as karate, which rely more on striking techniques. Striking techniques were seen as less important in most older Japanese systems because of the protection of samurai body armor and were used as set-ups for their grappling techniques. However, many modern-day jujutsu schools include striking, both as a set-up for further techniques or as a stand-alone action.

In jujutsu, practitioners train in the use of many potentially fatal moves. However, because students mostly train in a non-competitive environment, the risk is minimized. Students are taught break falling skills to allow them to safely practice otherwise dangerous throws.

5. Schools and Derivations

As jujutsu has so many facets, it has become the foundation for a variety of styles and derivations today. As each instructor incorporated new techniques and tactics into what was taught to him originally, he codified and developed his own ryu (school) or Federation to help other instructors, schools, and clubs. Some of these schools modified the source material enough that they no longer considered themselves a style of jujutsu.

C. 1600 there were over 2000 Japanese jujutsu ryū, most with common characteristics. Specific technical characteristics varied from school to school. Many of the generalizations noted above do not hold true for some schools of jujutsu. Schools of Japanese jujutsu with long lineages include:

- Asayama Ichiden-ryū 浅山一傳流

- Dait%C5%8D-ry%C5%AB Aiki-j%C5%ABjutsu

- Fusen-ryū不遷流

- Hongaku Kokki-ryū 本覚克己流

- Hontai Yōshin-ryū 本體楊心流(Takagi Ryu)高木流

- Iga-ryū 為我流

- Iga-ryūha-Katsushin-ryu 為我流派勝新流柔術

- Ishiguro-ryū 石黒流

- Kashima Shin-ryū 鹿島神流

- Jishukan-Ryu

- Kensō-ryū 兼相流

- Kiraku-ryū 気楽流

- Kitō-ryū 起倒流

- Kukishin-ryū九鬼神流[10]

- Kyushin-ryū

- Natsuhara-ryū 夏原流(夢想直伝流)

- Sekiguchi-ryū 関口流

- Shindō Yōshin-ryū 神道楊心流

- Shibukawa-ryū 渋川流

- Sōsuishi-ryū 双水執流

- Takenouchi-ryū 竹内流

- Tatsumi-ryū 立身流

- Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū 天神真楊流

- Tennen Rishin-ryū 天然理心流

- Yagyū Shingan-ryū 柳生心眼流

- Yōshin-ryū 楊心流

5.1. Martial Arts Influenced or Derived from Jujitsu

Some examples of martial arts that have developed from or have been influenced by jujutsu are: aikido, bartitsu,[11] hapkido, judo (and thence Brazilian jiu-jitsu and sambo), kajukenbo, krav maga, kapap, pangamot, and kenpo.

Some schools also went on to influence modern Japanese karate. A major Japanese divergence occurred in 1905 when a number of jujutsu schools joined the Kodokan. The relationships between schools and styles can be complex. For example, the Wado-ryu school of karate is partially descended from Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu, itself in turn influenced by Okinawan karate.[12]

5.2. Aikido

Aikido is a modern martial art developed in the 1910s and 1930s by Morihei Ueshiba from the system of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu techniques to focus on the spiritual principle of harmony which distinguishes Budō from Bujutsu. Ueshiba was an accomplished student of Takeda Sokaku. Aikido is a systemic refinement of defensive techniques from Aiki-Jujutsu in ways that are intended to prevent harm to either the attacker or the defender. Aikido evolved much during Ueshiba's lifetime, so earlier styles (such as Yoshinkan) are more like the original Aiki-Jujutsu than ones (such as Ki-Aikido) that more resemble the techniques and philosophy that Ueshiba stressed towards the end of his life.

5.3. Bartitsu

Jujutsu was first introduced to Europe in 1898 by Edward William Barton-Wright, who had studied Tenjin Shinyō-ryū and Shinden Fudo Ryu in Yokohama and Kobe. He also trained briefly at the Kodokan in Tokyo. Upon returning to England he folded the basics of all of these styles, as well as boxing, savate, and forms of stick fighting, into an eclectic self-defence system called Bartitsu.[11]

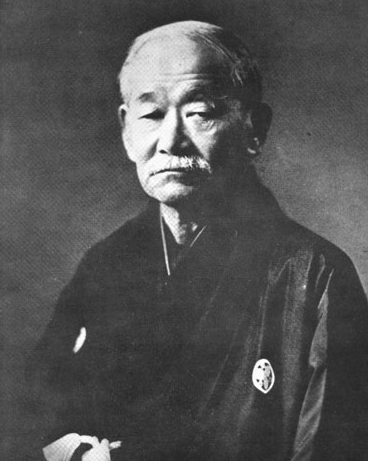

Judo

Modern judo is the classic example of a sport that derived from jujutsu and became distinct. Many who study judo believe as Kanō did, that judo is not a sport but a self-defense system creating a pathway towards peace and universal harmony. Another layer removed, some popular arts had instructors who studied one of these jujutsu derivatives and later made their own derivative succeed in competition. This created an extensive family of martial arts and sports that can trace their lineage to jujutsu in some part.

The way an opponent is dealt with also depends on the teacher's philosophy with regard to combat. This translates also in different styles or schools of jujutsu. Because in jujutsu every conceivable technique is allowed (including biting, hair-pulling, eye-gouging, and striking the groin), there is unlimited choice of techniques. By contrast, judo emphasizes grappling and throwing, while karate emphasizes punching or kicking.

Not all jujutsu was used in sporting contests, but the practical use in the samurai world ended circa 1890. Techniques like hair-pulling and eye-poking were and are not considered acceptable in sport, thus, they are excluded from judo competitions or randori. However, Judo did preserve the more lethal, dangerous techniques in its kata. The kata were intended to be practiced by students of all grades but now are mostly practiced formally as complete set-routines for performance, kata competition, and grading, rather than as individual self-defense techniques in class. However, judo retained the full set of choking and strangling techniques for its sporting form and all manner of joint locks. Even judo's pinning techniques have pain-generating, spine-and-rib-squeezing and smothering aspects. A submission induced by a legal pin is considered a legitimate win. Kanō viewed the safe "contest" aspect of judo as an important part of learning how to control an opponent's body in a real fight. Kanō always considered judo a form of, and a development of, jujutsu.

A judo technique starts with gripping your opponent, followed by off-balancing them and using their momentum against them, and then applying the technique. Kuzushi (the art of breaking balance) is also used in jujutsu, where the opponent's attack is deflected using their momentum against them in order to arrest their movements then throw them or pin them with a technique— thus controlling the opponent. It is known in both systems, Kuzushi is essential in order to use as little energy as possible. Jujutsu differs from judo in a number of ways. In some circumstances, judoka generate kuzushi by striking one's opponent along his weak line. Other methods of generating kuzushi include grabbing, twisting, or poking areas of the body known as atemi points or pressure points (areas of the body where nerves are close to the skin – see kyusho-jitsu).

Brazilian jiu-jitsu

Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) was developed after Mitsuyo Maeda brought judo to Brazil in 1914. Maeda agreed to teach the art to Luiz França and Carlos Gracie, son of his friend, businessman and politician Gastão Gracie. Luiz França went on to teach it to Oswaldo Fadda. After Carlos learned the art from Maeda, he passed his knowledge to his brothers Oswaldo, Gastão Jr., and George. Meanwhile, Hélio Gracie would peek in and practice the techniques, although he was told he was too young to practice. At the time, judo was still commonly called Kanō jiu-jitsu (from its founder Kanō Jigorō), which is why this derivative of judo is called Brazilian jiu-jitsu rather than Brazilian judo. Its emphasis shifted to ground grappling because the Gracie family thought it was more efficient and much more practical. Carlos and Helio helped the development by promoting fights (mostly against practitioners of other martial arts), competitions and experimenting throughout decades of intense training. BJJ dominated the first large modern mixed martial arts competitions, causing the emerging field to adopt many of its practices. Less-practiced stand-up techniques in Gracie Jiu Jitsu remain from its judo and jujutsu heritage (knife defense, gun defense, throws, blocking, striking etc.).

Sambo

Sambo is a Russian martial art and sport derived from Japanese Judo and traditional Central Asian styles of folk wrestling. One of Sambo's founders, Vasili Oschepkov, was one of the first foreigners to learn Judo in Japan and earned a second-degree black belt awarded by Kanō Jigorō himself. Modern sports Sambo is similar to sport Judo or sport Brazilian jiu-jitsu with differences including use of a jacket and shorts rather than a full keikogi, as well as, a higher occurrence of leglocks.

Modern schools

After the transplantation of traditional Japanese jujutsu to the West, many of these more traditional styles underwent a process of adaptation at the hands of Western practitioners, molding the art of jujutsu to suit western culture in its myriad varieties. There are today many distinctly westernized styles of jujutsu, that stick to their Japanese roots to varying degrees.

Some of the largest post-reformation (founded post-1905) jujutsu schools include (but are certainly not limited to these in that there are hundreds (possibly thousands), of new branches of "jujutsu"):

- Danzan-ryū

- German ju-jutsu

- Jigo Tenshin Ryu

- Atemi Ju-Jitsu

- Hakkō-ryū

- Shorinji Kan Ju Jitsu

- Small Circle JuJitsu

Sport jujutsu

There are many types of Sports Jujutsu. One version of Sports jujutsu is known as "JJIF Rules Sports Ju-Jitsu", organized by Ju-Jitsu International Federation (JJIF), and has been recognized an official sport of the World Games.

Sport Jujutsu comes in three main variants: Duo (self-defense demonstration) where both the tori (attacker) and the uke (defender) come from the same team and demonstrate self-defense techniques. In this variant, there is a special system named Random Attacks, focusing on instilling quick reaction times against any given attack by defending and countering. The tori and the uke are also from the same team but here they don't know what the attack will be, which is given to the uke by the judges, without the tori's knowledge.

The second variant is the Fighting System (Freefighting) where competitors combine striking, grappling and submissions under rules which emphasise safety. Many of the potentially dangerous techniques such as scissor takedowns, necklocks and digital choking and locking are prohibited in Sport Jujutsu. There are a number of other styles of sport jujutsu with varying rules.[13][14]

The third variant is the Japanese/Ne Waza (grappling) system in which competitors start standing up and work for a submission. Striking is not allowed.

6. Heritage and Philosophy

Japanese culture and religion have become intertwined into the martial arts. Buddhism, Shinto, Taoism and Confucian philosophy co-exist in Japan, and people generally mix and match to suit. This reflects the variety of outlook one finds in the different schools.

Jujutsu expresses the philosophy of yielding to an opponent's force rather than trying to oppose force with force. Manipulating an opponent's attack using his force and direction allows jujutsuka to control the balance of their opponent and hence prevent the opponent from resisting the counterattack.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Jujutsu

References

- Takahashi, Masao (May 3, 2005). Mastering Judo. Human Kinetics. p. viii. ISBN 0-7360-5099-X.

- Kanō, Jigorō (2006) [2005]. "A Brief History of Jujutsu". in Murata, Naoki. Mind over muscle: writings from the founder of Judo. trans. Nancy H. Ross (2 ed.). Japan: Kodansha International. p. 13. ISBN 4-7700-3015-0.

- Skoss, Meik (1995). "Jujutsu and Taijutsu". Aikido Journal 103. http://www.aikidojournal.com/article.php?articleID=17. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- "儒学者 藤原惺窩 / 三木市". City.miki.lg.jp. http://www.city.miki.lg.jp/bunka/jugakusha.html. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- 日本武道全集. 第5巻. Shin-Jinbutsuoraisha. 1966. ASIN B000JB7T9U. https://www.amazon.co.jp/dp/B000JB7T9U

- Matsuda, Ryuichi (2004). 秘伝日本柔術. Doujinshi. ISBN 4-915906-49-3.

- Mol, Serge (2001). Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Complete Guide to Koryū Jūjutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International. pp. 24–54. ISBN 4-7700-2619-6.

- "Archived copy". http://www.perthmartialarts.com.au/jiu-jitsu/.

- "Jujutsu". Mysensei.net. 2009-02-09. http://mysensei.net/2009/02/09/what-is-jujutsu/. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- "A history of Kukishin Ryu". Shinjin.co.jp. http://www.shinjin.co.jp/kuki/hyoho/history01_e.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- "Bartitsu". http://www.fullcontactmartialarts.org/bartitsu.html.

- "和道流空手道連盟". Wado-ryu.jp. http://www.wado-ryu.jp. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

- "Jiu-Jitsu Rules". Cmgc.ca. http://www.cmgc.ca/jiu_jitsu_rules.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- "AAU Freestyle Jujitsu Rules" (PDF). http://www.ichoyamaryu.com/AAU/rules/06_Jujitsu_Handbook.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-12.