There are many variations of the simple rules of Go. Some are ancient digressions, while other are modern deviations. They are often side events at tournaments, for example, the U.S. Go Congress holds a "Crazy Go" event every year.

- side events

- go

- digressions

1. National Variants

The difficulty in defining the rules of Go has led to the creation of many subtly different rulesets. They vary in areas like scoring method, ko, suicide, handicap placement, and how neutral points are dealt with at the end. These differences are usually small enough to maintain the character and strategy of the game, and are typically not considered variants. Different rulesets are explained in Rules of Go.

In some of the examples below, the effects of rule differences on actual play are minor, but the tactical consequences are substantial.

1.1. Tibetan Go

Tibetan Go is played on a 17×17 board, and starts with six stones (called Bo) from each color placed on the third line as shown. White makes the first move.[1] There is a unique ko rule: a stone may not be played at an intersection where the opponent has just removed a stone. This ko rule is so different from other major rulesets that it alone significantly changes the character of the game. For instance, snapbacks must be delayed by at least one move, allowing an opponent the chance to create life. Finally, a player who occupies or surrounds all four corner points (the 1-1 points) receives a bonus of 40 points, plus another 10 if the player also controls the center point.

1.2. Sunjang Baduk

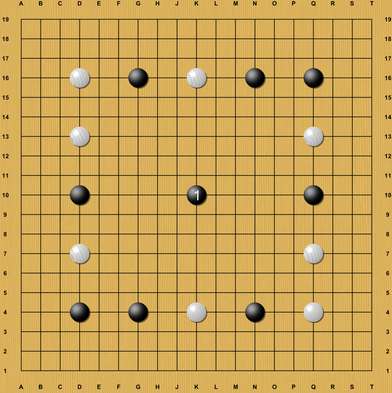

Sunjang baduk is a different form of Go (baduk) that evolved in Korea, which dates to the 16th century.[2] Its most distinctive feature is the prescribed opening. The starting position dictates the placement of 16 stones (8 black, 8 white) as shown, and the first move is prescribed for Black at the center of the board. At the end of the game, stones inside friendly territory, which are irrelevant to boundary definition, are removed before counting territory.

It became obscure in the 1950s when it was largely replaced by modern go due to Japanese influence. There are around 45 surviving game records of Sunjang baduk, mostly from the 1880s.[3] The oldest known game record was published in the Chosun Ilbo newspaper on March 1937, although the game was played much earlier. The game is between No Sa-ch'o and Ch'ae Keuk-mun.[4]

Classical Chinese go was played with the diagonal placement of two black stones and two white stones on the four star points in the corners. It is likely that Koreans played go in this form until it developed into Sunjang baduk in the 16th century. In the early 20th century, the top ten strongest players ranged from about 4 dan amateur to 2 dan professional in terms of strength.[5] From 1910–1945, Korea was a Japanese colony. The similarity between Sunjang Baduk and modern go as well as Japanese influence encouraged players to switch to the modern game. The strength and fame of visiting Japanese professional go players encouraged Koreans to abandon Sunjang baduk. This was supported by the father of modern Korean go, Cho Nam-ch'eol, who established close links to Japan by studying go there.[5]

1.3. Bangneki

In another Korean variant, bangneki, the players wager on the outcome of the game. A fixed stake ("bang") is paid for every ten points on the board by which the loser is beaten.[6][7]

1.4. Batoo

Batoo is a modern Korean variant. The name stems from a combination of the Korean words baduk and juntoo (“battle”). It is played entirely in cyberspace, and differs from standard Go in a number of ways, most noticeably in the way in which certain areas of the board are worth different points values. The other principal difference is that both players place three stones before the game begins, and may also place a special “hidden stone”, which affects the board as a regular stone but is invisible to the opponent. Batoo became a short-lived fad among young people in Korea around 2011.

2. Variants Altering the Rules of Play

2.1. First Capture

The first player to capture a stone wins. It was invented by Japanese professional Yasutoshi Yasuda, who describes it in his book Go As Communication. Yasuda was inspired by the need for a medium to address the problem of bullying in Japan, but soon found that "First Capture" also works as an activity for senior citizens and even developmentally delayed individuals. He sees it as a game in its own right, not just as a prelude to Go, but also as a way to introduce simple concepts that lead to Go. For the latter purpose, he recommends progressing to "Most Capture", in which the player capturing the most stones wins. This variation is often called Atari Go in the West, where it is becoming increasingly popular as a preliminary means of introducing Go itself to beginners, since, afterward, it is natural to introduce the idea of capturing territory, not just the opponent's stones.

2.2. Miai-Go

In Miai-Go, each player plays two moves at once, and their opponent decides which of the two should stay on the board.

2.3. Stoical Go

In Stoical Go, invented by abstract game designer Luis Bolaños Mures, standard ko rules don't apply. Instead, it's illegal to make a capture if your opponent made a capture on the previous move. All other rules are the same as in Go. Suicide of one or more stones is not allowed, and area scoring is used.[8]

All known forced Go cycles are impossible with this rule. The nature of the rule itself suggests that forced cycles are either impossible or astronomically rarer than they are in Go when the superko rule is not used.

Ko fights proceed in a similar manner to those of Go, with the difference that captures and moves answered by captures aren't valid ko threats. Although snapbacks are not possible in the basic variant (as it is necessary to make a ko threat before any consecutive capture occurs), they can be explicitly allowed with an extra rule while retaining the property that all known forced cycles are impossible.

2.4. Environmental Go

Environmental Go, also called Coupon Go,[9] invented by Elwyn Berlekamp, adds an element of mathematical precision to the game by compelling players to make quantitative decisions.[10] In lieu of playing a stone, a player may take the highest remaining card from a pack of cards valued in steps of ½ from ½ to 20: the player's score will be the territory captured, plus the total value of cards taken. In effect, the players participate in a downward auction for the number of points they think sente is worth at each stage in the game. The professional players Jiang Zhujiu and Rui Naiwei played the first Environmental Go game in April 1998. Since then the variant has seen little activity on the international scene.

2.5. Time Is Money Go

Each player begins the game with a decided upon amount of time (no byoyomi). At the end of the game, when the score is counted, the number of seconds remaining on each player's clock is added to their respective score.

2.6. Cards Go

In Cards Go players draw from a pack of cards contain instructions to play one of a fixed set of commonly occurring shapes.[11] If the said shape cannot be placed on the board, then an illegal move is deemed to have been played, which necessitates resignation.

2.7. Multi-Player Go

In Multi-player Go, stones of different colors are used so that three or more players can play together. The rules must be somewhat altered to create balance in power, as those who play first (especially the first four, on a four-cornered board) have significant advantage.[12]

There are various optional rules that enable cooperation between the players, e.g. division of captured stones among neighbors, or forming alliances for adding up territory points.[12] A variant called parallel multiplayer go also exists, where the moves are announced simultaneously. If two moves overlap, they count as passes.[12]

2.8. Paper and Pencil Go

Paper and Pencil Go is a Go variant that can be played with just paper and pencil.[13] Unlike standard Go, games played under these rules are guaranteed to end in a finite number of moves, and no ko rule is needed. Nothing is ever rubbed out. It differs from standard Go in the following ways:

- Surrounded stones are not captured, but just marked. Points occupied by marked stones count as territory for the surrounding player, but neither player can play on them for the remainder of the game. This implies that any group which touches a marked stone is unconditionally alive.

- Suicide is allowed, i.e., you can make a play such that one or more of your own stones become marked.

- Area scoring is used.

(Conventional Go can also be played on paper by drawing circles of different colors. Captured stones are marked with a line. Then if the square is replayed, a smaller circle is placed inside the larger circle.[14])

2.9. Omino Go

Also named Tetromino Go. Devised by R. Wayne Schmittberger, each player is allowed to play up to four stones in a turn, provided they are solidly connected on adjacent points. (There are five four-stone patterns possible, two three-stone patterns, and one two-stone pattern, ignoring rotations and reflections.) There is no komi; Black is restricted on his first turn to playing no more than two stones. The winner is determined by Chinese scoring: occupied and surrounded points each count 1 point; captured stones do not have point value. The inventor suggests a 15×15 square-celled board using square-tiled pieces.[15]

2.10. NoGo

The first player forced to capture one or more stones or to make a suicide move loses. Players try forcing their opponent into a losing move by building territory only they can play on.

2.11. KillAll Go

In this variant, black is given a large handicap, and must prevent white from forming a stable group.

2.12. Quantum Go

Quantum Go is a Go variant which provides a straightforward illustration of interesting quantum phenomena.[16] Players alternatively play pairs of go stones which are entangled, in the sense that each entangled pair of stones will reduce to a single go stone at some point in the game. A process of quantum-like collapse occurs when a stone is played in contact with one of the stones in an entangled pair.

2.13. Block Go

Block Go was a variant of Go played at the 20th Annual Computer Olympiad in which tetris pieces are utilized instead of go stones.

2.14. Two Stone Go

All standard rules apply, but after the Black (the first player) places one stone on the very first move both players place two stones each subsequent turn (similar to the game of Connect6). Since each player has an alternating one stone advantage at the end of their respective turns, there is no strong need for Komidashi (compensation for playing second) in games between even-strength players.

2.15. Borderless Go

In this variant, intersections at the opposite sides of the board are considered adjacent, like on a torus. Therefore the playing board has no corners or sides and standard opening strategies that focus on capturing those parts of the board do not apply.

2.16. Sygo

Sygo is a two player abstract strategy game invented in 2010 by Christian Freeling. It differs from Go by using a move protocol from Symple, another of Christian Freeling's games, and "othelloanian capture" where stones change colors when captured instead of being removed from the board. The goal of Sygo is to control the most territory on the board as determined by the number of a player's stones on the board as well as the empty points completely surrounded by the players stones. The game ends when one player either resigns or both players pass on successive turns.

3. Variants for More Than Two Players, but Not Altering the Mechanism of the Game

3.1. Rengo

Rengo (Japanese: 連碁) involves two teams of players taking either the Black or the White stones. Each player in the team must play in turn, playing out of sequence will normally result in a small penalty (usually three prisoners). Partners may not consult on how to play, or engage in any form of signaling. Communication between partners may only take the following forms listed below.

- May we resign? can be answered with yes or no

- How much time is left? can be answered.

- Whose turn is it?

3.2. Pair Go

Pair Go is a competitive game played by two pairs, with each team consisting of a male and a female, sharing a single Pair Go board. The pairs play alternately: first, the female player of the two holding black; next, the female player of the pair holding white; next, the male player of the pair holding black; and next, the male player of the pair holding white.[17] It was popularised by the Japan Pair Go Association as a means of increasing female participation in the game. They hoped that this increase in itself would add a new appeal to the game. The Ricoh Cup, the annual professional Pair Go world championship debuted in 1994.[18] The International Pair Go Association sponsors an annual amateur world championship in Tokyo in November, which has been running uninterrupted since 1989.[19] They first introduced the variant to Europe at the 1992 European Congress in Canterbury, England. Amateur Pair Go tournaments have been held in the United States at the U.S. Go Congresses since 2005 at least [20] and in Denver, Colorado.

4. Variants Requiring Memory of the Position

4.1. Blind Go

One (as a handicap) or both of the players cannot see the board in this variant. Therefore, they have to remember the whole position. This is considered much more difficult than playing blindfold chess. A few club standard players can play blindfold chess, but only professional players are able to complete a game of blind 19×19 Go.

4.2. One Color Go

The two players use stones of the same color. This variation is regarded as a useful tool for developing one's memory and reading skills by forcing both players to remember who placed each stone. An external program or a third person may be used to keep track of who captures what in case one or both players forget the true color of a stone.

5. Variants with Limited Knowledge of the Position

These variants are not purely strategic games, as the element of luck is quite important.

5.1. Shadow Go

This game requires two players, a referee and three playing sets. Each player sees only his own board, while the referee can see them both and also has his own set. This variant is usually played on a 9×9 board. Players place stones on their boards, with no knowledge of what other players are doing. A referee keeps track of the game on the central board. If any player makes an illegal move, the referee informs him about it (some play that the referee says only that the move is illegal, while some, that the player is told whether the intersection is occupied or there is illegal ko capture). The player is allowed to make another move.

5.2. Rengo Kriegspiel

This is a crossover between rengo and shadow Go. There are two teams with two players each, a referee and five Go sets. The players move alternatingly as in rengo. Each player keeps track of their own moves on their own board; they are not informed about teammates' or opponents' moves. The referee keeps track of the complete game and informs a player if their move was illegal, in which case they can try again. The referee removes captured stones from all affected boards.[21]

6. Non-standard Boards

Although Go is most commonly played on a board with 19×19 lines, 9×9 and 13×13 boards are also available. They are used by beginners and by players who want a game that finishes more quickly. Due to flexibility of configuration, the two smaller sizes are more often played on the online Go servers such as KGS Go Server, and board sizes from 2×2 to 38×38 are also allowed.

The annual Milton Keynes Go Tournament has a popular side-event that is played on a stylised map of Milton Keynes.[22] Its non-conventional lattice presents some interesting possibilities.

Harald Schwarz invented a Go variant that is played on a circular lattice.[23]

Toroidal is played on a two-dimensional doughnut shaped surface. It can be played on a computer app[24] or simulated on a standard board, but requires imagination on the part of the players to perform an abstract join at the edges. Tactics become more elegant without the need for special border and corner cases (joseki) since a toroidal board has only "middle" space.

TriGo uses a triangular-grid goban, where each stone has up to six liberties. To compensate for this, there are several rule changes: ko and superko are limited in scope, komi is not used, and after the first stone is placed, every turn consists of placing two stones. After both players have passed a turn, the score is counted (the sum of captured stones and territory), and in the case of a draw the player passing first wins.

TriPlan, for three players, uses a triangular grid, where each stone has up to six liberties. Stones can be captured in two ways. If one player's stones are surrounded by those of one opponent, the surrounding player captures them and counts them as points at the end of the game. If one player's stones are surrounded by those of both opponents, they must be played as the surrounded player's next turn. If a player resigns, the two other players will determine who continues the game against the other two. That player will play alone, aiming to achieve a higher minimum score at the end of the game. At the end all captured stones and all stones on the board are counted. If the player reach his achieved goal, he wins. If the lone player doesn't reach the goal, the other two win the game. If there were no resignations, the player with the most points wins.[25]

Hexagonal Go, like hexagonal chess, played on boards composed of hexagon cells, where each stone has up to six liberties.

Other 2D variants can also be performed with edges joined in three other ways, resulting in a topological sphere, Klein bottle or real projective plane. Multiple boards can be used to form other Riemann surfaces.

6.1. Other than 2D

Alak is a Go-like game restricted to a single spatial dimension. Go can be extended to three dimensions. One example is Diamond Go, which uses the structure of a carbon diamond crystal lattice.[26] With many Go variants, the nature of the game changes dramatically when the standard four connections per point is changed. Diamond Go, however, maintains this connectivity. Another example is Margo, by Cameron Browne, a variant played with marbles that can be stacked on top of one another.[27]

A program called Freed Go can be used to play with boards with generic topology. It has embedded 11 different boards, either three-dimensional shapes (including cube, sphere, cylinder, diamond, torus and Möbius strip) or flat fields with points connected to three, five or six neighboring points, but it's also possible to create custom boards.[28]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Software:Go_variants

References

- "Tibetan Go at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?TibetanGo.

- History of Korean baduk, Korean Baduk Association, http://english.baduk.or.kr/sub01_01.htm?menu=f11, retrieved 2008-11-13

- Chi-hyung, Nam (2006), Lesson 35: Sunjang Baduk, http://www.times.hankooki.com/lpage/culture/200603/kt2006030515011765560.htm, retrieved 2014-04-02

- Fairbairn, John (2006), Historic: Sunjang Go OLDEST KNOWN GAME, http://www.msoworld.com/mindzine/news/orient/go/history/sunjang.html, retrieved 2014-04-02

- .Fairbairn, John (2000), Historic: Sunjang Go, http://www.msoworld.com/mindzine/news/orient/go/history/sunjang.html, retrieved 2014-04-02

- "Bang Neki at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?BangNeki.

- Hong, Sung-Hwa (1999). First Kyu. Good Move Press. ISBN 978-0-9644796-9-2.

- "Stoical Go at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?StoicalGo.

- "Coupon Go | School of Mathematics". http://www.math.ias.edu/seminars/abstract?event=13782.

- "Environmental Go at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?EnvironmentalGo.

- "Cards Go at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?CardsGo.

- "Go - Other Players". http://www.di.fc.ul.pt/~jpn/gv/players.htm.

- "Paper and Pencil Go at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?PaperAndPencilGo.

- "Free printable paper and pencil Go and shogi at Sensei's Library". https://senseis.xmp.net/?FreePrintablePaperAndPencilGoAndShogi.

- Schmittberger, R. Wayne (1992). New Rules for Classic Games. John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-0471536215. https://archive.org/details/newrulesforclass00rway/page/62.

- Ranchin, André (March 17, 2016). "Quantum Go". arXiv:1603.04751 [quant-ph]. //arxiv.org/archive/quant-ph

- "Welcome to Pair Go". http://www.pairgo.or.jp/home.htm.

- "Pair Go RICOH CUP 2009 [ Past Results "]. http://www.pairgo.or.jp/RICOH/2009/past_results_e.htm.

- "International Amateur Pair Go Championship". http://www.pairgo.or.jp/amateur/index_e.htm.

- "U.S. Go Congress 2005". http://www.usgo.org/congress/2005/.

- Bob High, Deviant Go , The American Go Journal, Volume 24:1 Winter 1990 http://www.usgo.org/resources/downloads/deviantgo.pdf

- "Milton Keynes Go Board | British Go Association". http://www.britgo.org/clubs/mk/mkboard.html.

- "Go". http://www.youdzone.com/go.html.

- Torogo - Free Android Game of Toroidal Go http://torogo.org

- "Spielregeln zum Strategie-Brettspiel Tri-Plan". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcBTDLfHAJk.

- "Diamond Go". http://www.segerman.org/diamond/.

- "Margo". http://www.cameronius.com/games/margo/.

- "Freed Go - The Game of Go in 3D - Lewcid.com". http://www.lewcid.com/lg/lc/freedgo.html.