This paper uses the concept of urban commons to develop a conceptual framework to inform the design and management of shared residential landscapes in the UK. The framework is founded on an exploration of the implications of applying the traditional ‘commons’ idea within the urban context. Urban spatial concepts and theories, such as informal urbanism, territory, placekeeping and partnerships, are drawn upon to build these implication into a framework that provides a new urban, spatial and place perspective on the urban commons concept. In addressing the urban implications for commons through spatial theories, four preliminary concepts are developed. These include; 1) the emergent common mindset in a complex-adaptive assemblage, 2) a spatial arrangement that reflects a shared territorial perception of ‘ours’, 3) opportunities for adaption and occupation of space as placemaking and 4) the reorientation of professional roles in delivering urban commons. The framework creates a foundation for further research on the design and long-term management of shared residential landscapes as urban commons to benefit the everyday social lives of residential communities.

- urban commons

- residential landscapes

- spatial theory

- cohousing

- governance

- shared resources

- territory

- urban design

- shared landscapes

1. A Conceptual Framework for Urban Commons in Residential Landscapes

This paper defines commons as a shared resource, collectively governed by a community of end users that maintain a bottom-up and inclusive approach to participation. A review of urban commons literature reveals several spatial, social and institutional implications of applying commons theory within the urban context. These include 1) the enablers of collective governance between strangers in the city, 2) understanding the spatial implications of sharing resources within the city, 3) the impact of collective governance on the creation of place and 4) the need for community groups to work within institutional urban frameworks. A preliminary conceptual framework for applying commons theory within an urban residential context (see Figure 1) draws upon various spatial theories in addressing some of these implications. In doing so, this paper outlines four preliminary concepts for applying commons theory to the urban context 1) the emergent common mindset in a complex-adaptive assemblage, 2) a spatial arrangement that reflects a shared territorial perception of ‘ours’, 3) opportunities for adaption and occupation of space as placemaking and 4) the reorientation of professional roles in delivering urban commons. The four concepts are summarised in Figure 1 and the following paragraphs briefly explore how these concepts were developed from a literature of traditional commons theory and urban spatial theory.

Figure 1. The urban commons framework consists of (1) the defining components of a commons, (2) the implications for these components in the urban context, (3) the relevant spatial concepts and theory in addressing the urban implications and (4) the key spatial ideas for the application of the urban commons in residential landscapes.

2. Working Together as Strangers

To explore the spatial implications of urban commons, the framework begins by looking at what drives their initial formation. Ostrom marks the success of commoning as relying on communities that “share a past, and expect to share a future"[1]. Therefore, the relatively close-knit and stable characteristics of rural communities compel individuals to work together in anticipation of long-term mutual benefit and trust. In contrast, the city is characterised by a dense saturation of people living as relative strangers[2][3]. Urban commons emerge without the default commonality and established trust of rural communities—a prerequisite to commons formation. Examples of urban commons in recent research demonstrate emergence in response to privatisation and limitations on urban life[4], tenants in danger of eviction[2], campaigns against demolition and in support of neighbourhood revitalisation[5] and movement against climate change[6]. These examples suggest that instead, urban commons form in response to a threat, need, desire or ideology. Huron[2] highlights in her research that within the city, there is a dialectic relationship between commons and community formation that differentiate urban commons from their rural counterparts. Community is not a prerequisite to urban commons formation, but rather a simultaneous process of commoning and community formation triggered by a particular urban condition that drives a common mindset.

3. A Spatial Understanding of Urban Commons

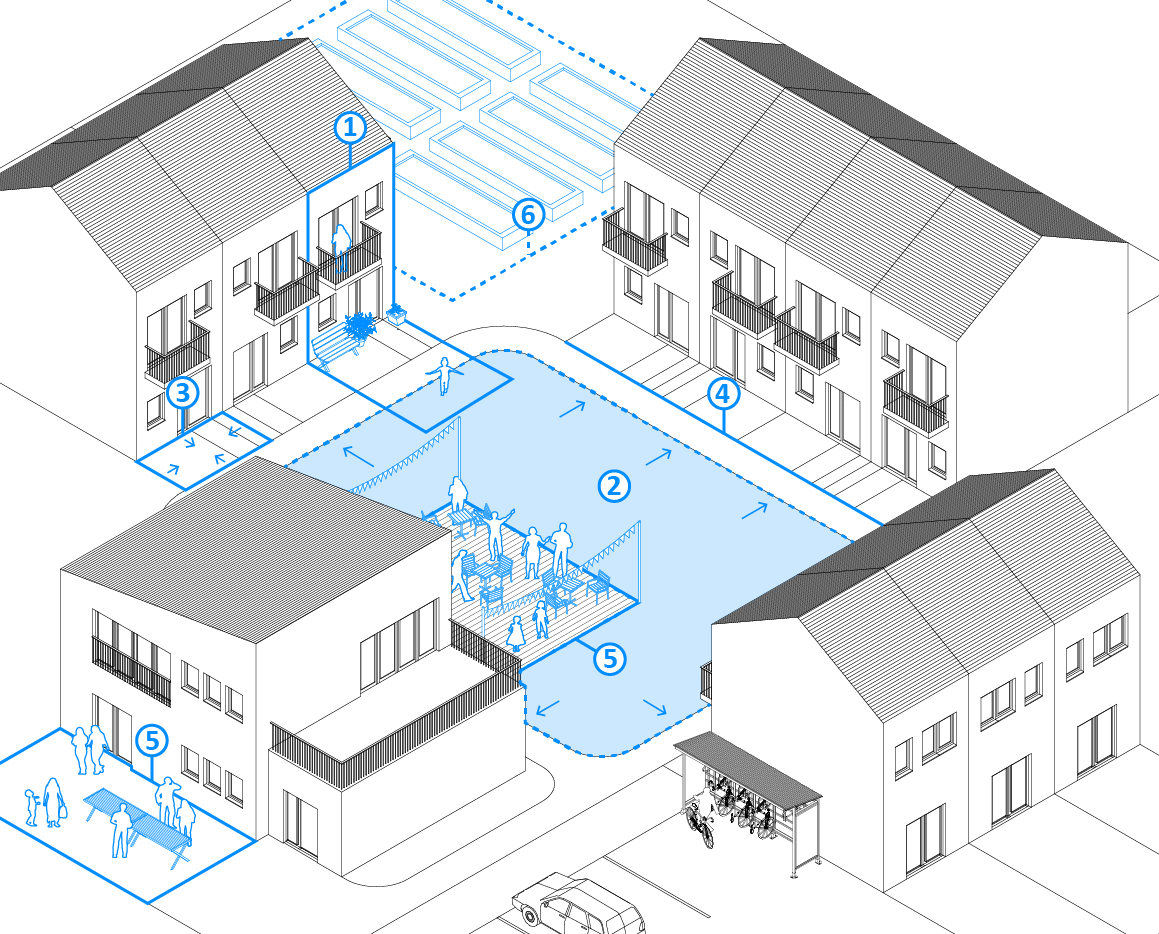

Urban contexts bring together both social and spatial considerations. The previous section outlines the implications of some of the social characteristics of the urban, living amongst strangers. The current section will now explore the spatial implications. The ‘urban’ describes a size, scale, density, diversity and temporality[7], all of which are descriptors of the city’s physical form. Urban commons, by the definition of what is urban, have spatial as well as social implications[8][9]. To define what is meant by space, this paper looks toward a multi-faceted understanding outlined by Lefebvre: the abstract mental construction of space, the production of physical space, and the experience of living in and through space. Through this understanding, urban commons are recognised simultaneously as being spatially perceived in the minds of commoners, physically conceived through collective action and experienced through everyday occurrences. Urban commons are at once a product of the city and a producer of urban space, concurrently experienced by commoners[10]. Therefore, the implication for the theory of urban commons is that our understanding is not limited to a spatial form created by collective action nor solely a social organisation produced from a spatial resource; rather they emerge from the reciprocal relationship between both—a socio-spatial manifestation. Such a mindset inherently places significance upon the linkage between such social and spatial considerations, which, when viewed within the context of commons thinking, can be reflected upon in terms of shared territory or "our space". The key spatial principles relating to "our space" within shared residential landscapes are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A diagram illustrating the key spatial principles of urban commons in a shared residential landscape: (1) proximity of ‘mine’ and ‘ours’; (2) central shared landscape as our space; (3) reduction in private space; (4) thin boundaries between ‘mine’ and ‘ours’ (no hedges or fences); (5) flexible shared spaces that afford public events; (6) loose space left for community self-finish.

4. The Production of Urban Commons as Placemaking

To date, in its evolving definition, urban commons are considered as both a long-term process of sustaining a shared resource[11] and a short-term goal of reclaiming spaces in the city[2]. Huron, identifies that within the urban context, following successful reclaiming of urban resources, there is a need for that resource to be maintained through long-term governance. The adaption of urban spatial resources through their initial acquisition and longer-term governance to suit the everyday needs of urban residents, therefore, influences the spatial, social, political, cultural and material dimensions of that resource. Place is a word that can be used to describe the coming together of the multiple dimensions associated with urban spatial resources. Dovey[11] highlights that place distinguishes itself from space by describing a measure of intensity, such as vibrancy, activity or other qualitative characteristics that the dimensional measures of space cannot portray. In the case of urban commons, place is a useful term to describe the developing product between an urban spatial resource and the social dimensions of collective governance and the process of commoning. Placemaking describes an approach to delivering places in a way that strengthens the connections between people and place[12] and placekeeping is a term that emphasises the role of long-term and ongoing practices of maintenance, management and governance in the creation of place[13]. Together, placemaking and placekeeping describe the process through which urban commons are realised spatially through the everyday activities, perception and participation of end users through collective governance.

The factors that influence placemaking are complex and multiplicious. Franck and Stevens[14] use the term ‘loose space’ to summarise the characteristics that enable people to appropriate and adapt space to meet their needs and desires. ‘Looseness’ relies largely upon individual people’s belief of what is admissible or allowed a belief in their abilities, skills and recognition of new possibilities. Therefore, loose spaces provide physical opportunities for looseness, people’s perceived potential to create place, to be fulfilled. According to Franck and Stevens[15], the characteristics of loose space relate to spatial diversity, physical disorder and affordance. Firstly, greater spatial diversity, the variation in physical form, creates increased possibilities for how that space can be inhabited and adapted and by whom. Secondly, physical disorder relates to a lack of regulation, lower surveillance, visible physical deterioration and ambiguity in the control of space that allows individuals increased freedom to take ownership of space. Lastly, affordance describes the ability for physical features to provide multiples uses, the occupation of space enabled by graduated transitions at thresholds and moveable, flexible and malleable elements. While spatial diversity, physical disorder and affordance hinge on increased flexibility and reduced definition, a lack of spatial elements and too much openness can also restrict opportunities. Dovey describes this as a tension between stable, enclosed territories and the absence of defined territorial boundaries[15]. He describes a tension within place that is constantly shifting with spaces having the potential to accommodate new and unpredictable forms of placemaking that stabilise in time toward enclosed territories until the cycle begins again. The crux of loose space and the encouragement of placemaking through forms of urban commoning centres on the provision of spatial form that can be readily adapted and the relinquishment of some level of control, definition and prescription in favour of flexibility, adaption and the unknown.

5. Partnerships and Collaborations

The urban context creates several challenges for bottom-up movements, such as commons, to take hold, due to the difficulties in navigating its numerous top-down frameworks, such as planning and legal systems[16]. While some urban commoners may utilise knowledge from within their group where they comprise members with professional positions and specialist knowledge, many require support, partnerships, collaborations or consultation with external professions and organisations to negotiate such frameworks. This may be in the form of support, guidance and open-mindedness from housing associations, tenants and residents associations and local councils, or advisory roles and participative approaches from design professions. Within urban commons, there is a shift away from traditional client-professional relationships towards a collaborative or supportive partnership between bottom-up and top-down actors. The placekeeping conceptual framework[17] describes a shift away from a single universal governing body toward a liaison among a variety of stakeholders in the delivery of place. Successful approaches to place governance combine local knowledge, skills, time and resources with external resources, professional expertise and public enablement. Despite these benefits, there continues to be several barriers to community involvement in the design and maintenance of urban residential spaces. A contributing factor to this problem is the polarisation between top-down and bottom-up approaches to design, implementation and management in urban development[18][19]. The predominant top-down approach to residential placemaking in the UK today creates barriers to people focused placemaking and a disjointed and uncoordinated approach to its long-term place maintenance and management[19].

A recent political shift toward localism, alongside austerity measures and local authority withdrawal from the public realm in the UK[6] has created regulatory slippages[20] in top-down placemaking provision that community-led approaches have been able to occupy[21]. Research into this phenomenon, described as ‘improvised’, ‘interstitial’ and ‘makeshift’ urbanism (amongst others)[22], demonstrates a number of potential benefits, including improved quality of space[5][22], social interaction and community cohesion[23], and individual wellbeing and expression of self-identity[24]. However, such examples also demonstrate significant barriers to bottom-up participation in placemaking within institutional, legal and design frameworks[5], a lack of empowerment to influence external authorities and relations[4], and a limited capacity for resources, skills and time[25]. Ostrom’s last principle for common-pool resources attempts to address issues of scale and power through the implementation of multiple layers of nested institutional rules[1] that enable both top-down and bottom-up approaches to work together. Thus, the success of urban commons relies on maintaining open communication channels from the bottom to the top to enable a common mindset to extend beyond internal relationships to include external professions, organisations and institutions.

The emergence of commons within the urban context not only calls for collaborations between communities and urban professionals but a new facilitating role to enable such change to happen. This can be explained using Arnstein’s ladder of participation[26]. The participative relationship between urban commons communities and professions, organisations and institutions is positioned on the top three rungs of the ladder of participation (citizen control, delegated power, and partnership; see Figure 3). Any position lower down the ladder would hinder the commoners’ ability to maintain collective participation in devising, monitoring, sanctioning and resolving their own rules[1], a defining characteristic of a commons. Therefore, the role of the urban professional needs to shift to reflect this new relationship, from client-profession to one of supporter, facilitator and partner. This requires a willingness of urban professions to relinquish some level of control and a preparedness to work with the unknown.

Figure 3. Urban Commons are defined by the collective ability of commoners to participate in its governance, situating them on rungs 6-8 on Arnstein’s ladder of participation. Below these rungs, in the zones of ‘Tokenism’ and ‘Non-participation’, commoners lack the necessary control to define their own rules, and therefore their status as a commons. Adapted from Arnstein’s ladder of participation[26].

References

- Elinor Ostrom. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 88.

- Amanda Huron; Working with Strangers in Saturated Space: Reclaiming and Maintaining the Urban Commons. Antipode 2015, 47, 963-979, 10.1111/anti.12141.

- L.H. Lofland,. A World Of Strangers: Order and Action in Urban Public Space; Basic Books, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. ..

- Patrick Bresnihan; Michael Byrne; Escape into the City: Everyday Practices of Commoning and the Production of Urban Space in Dublin. Antipode 2014, 47, 36-54, 10.1111/anti.12105.

- Matthew Thompson; Between Boundaries: From Commoning and Guerrilla Gardening to Community Land Trust Development in Liverpool. Antipode 2015, 47, 1021-1042, 10.1111/anti.12154.

- Julian Dobson; From ‘me towns’ to ‘we towns’: activist citizenship in UK town centres. Citizenship Studies 2017, 21, 1015-1033, 10.1080/13621025.2017.1380605.

- Louis Wirth; Urbanism as a Way of Life. American Journal of Sociology 1938, 44, 1-24, 10.1086/217913.

- Eleni Katrini; Sharing Culture: On definitions, values, and emergence. The Sociological Review 2018, 66, 425-446, 10.1177/0038026118758550.

- D. Harvey. Rebel cities: From the Right to the City to the Right to the Urban Revolution; Verson: London, UK, 2012; pp. ..

- Henri Lefebvre. Writing on Cities; E. Kofman, E. Lebas, Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; pp. ..

- Kim Dovey; Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. International Development Planning Review 2012, 34, 349-368, 10.3828/idpr.2012.23.

- What Is Placemaking? . Project for Public Spaces. Retrieved 2019-11-13

- Nicola Dempsey; Mel Burton; Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2012, 11, 11-20, 10.1016/j.ufug.2011.09.005.

- K.A. Franck; Q. Stevens. Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2006; pp. ..

- Kim Dovey. Becoming Places: Urbanism/Architecture/Identity/Power; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010; pp. ..

- H. Jarvis; K. Scanlon.; M. Fernández Arrigoitia; P. Chatterton; A. Kear; D. O’Reilly; L. Sargisson; F. Stevenson. Cohousing: Shared Futures. 2016. UK Cohousing Network website. https://cohousing.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Cohousing-shared-futures-2016.pdf.

- Nicola Dempsey, Harry Smith, Mel Burton, (Eds). Place-Keeping: Open Space Management in Practice; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2014; pp. ..

- Runrid Fox-Kämper; Andreas Wesener; Daniel Münderlein; Martin Sondermann; Wendy McWilliam; Nick Kirk; Urban community gardens: An evaluation of governance approaches and related enablers and barriers at different development stages. Landscape and Urban Planning 2018, 170, 59-68, 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.023.

- Ali Madanipour; Konrad Miciukiewicz; Geoff Vigar; Master plans and urban change: the case of Sheffield city centre. Journal of Urban Design 2018, 23, 465-481, 10.1080/13574809.2018.1435996.

- Sheila Foster; Christian Iaione; The City as a Commons. Yale Law Policy Review 2016, 34, 281-349, https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/ylpr/vol34/iss2/2.

- Fran Tonkiss; Austerity urbanism and the makeshift city. City 2013, 17, 312-324, 10.1080/13604813.2013.795332.

- M. Dennis; P. James; User participation in urban green commons: Exploring the links between access, voluntarism, biodiversity and well being. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2016, 15, 22-31, 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.11.009.

- Julie Ober Allen; Katherine Alaimo; Doris Elam; Elizabeth Perry; Growing Vegetables and Values: Benefits of Neighborhood-Based Community Gardens for Youth Development and Nutrition. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition 2008, 3, 418-439, 10.1080/19320240802529169.

- Communities in Control. CiC Research Summary 1: How Is Collective Control Developing Among Residents Involved in the Big Local Programme?; 2015. Communities in Control website. https://communitiesincontrol.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CiC-Summary-1-Collective-Control-final.pdf

- Shared Assets. Transforming Derelict or Underused Land Through Community-Led Models: A Guide Inspired by the Experience of Our Place Projects; 2016. My Community, locality website. https://mycommunity.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/10-Reclaiming-land-v-4-FINAL-1.pdf

- Sherry R. Arnstein; A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 1969, 35, 216-224, 10.1080/01944366908977225.