The MET gene, known as MET proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase, was first identified to induce tumor cell migration, invasion, and proliferation/survival through canonical RAS-CDC42-PAK-Rho kinase, RAS-MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, and β-catenin signaling pathways, and its driver mutations, such as MET gene amplification (METamp) and the exon 14 skipping alterations (METex14), activate cell transformation, cancer progression, and worse patient prognosis, principally in lung cancer through the overactivation of their own oncogenic and MET parallel signaling pathways. Because of this, MET driver alterations have become recognized as actionable alterations in lung adenocarcinomas since the FDA approval target therapies for METamp and METex14 in 2020.

1. Introduction

The principal hallmark of tumorigenesis is cell transformation, involving the transition of normal cells into the tumorigenic state, which is characterized by the acquisition of enhanced cell proliferation and the activation of anchorage-independent growth, which could progress until activated cell migration, the invasion of tumor cells, and finally, metastasis. However, depending on the signaling pathways altered by the driver mutations, the tumor mass would be highly proliferative, invasive, angiogenic, and or metastatic [

1]. Until now, the driver mutations in genes such as EGFR, ALK, ROS1, HER2, and MET (among others) had demonstrated advantages favoring cell transformation, leading to tumor formation and progression, before these showed their actionability in lung cancer with target drugs, this means specific mutations in these genes are recognized as predictors of therapy responses.

The

MET gene encodes a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family of proteins, and, since the early 1980s, different authors have studied the effect of

MET on cancer development, starting by Cooper et al., who were the pioneers in described

MET gene as a “driver gene” when this concept did not exist yet, identifying it as a transforming gene detected in chemically transformed cells [

2]. Afterwards, Tward et al. found that the

METamp would be able to induce cell transformation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in mice overexpressing a wild-type allele of human

MET, although the carcinoma only arose in cooperation with the constitutively active β-catenin expression [

3]. Perhaps this was possible through the crosstalk signaling Met/β-catenin since the inactivation of

MET transgenes induced the regression of HCC [

4]. In the same way, Mi et al., speculated whether MET could have initiated tumorigenesis in mice prostates, so they tested this idea designing a conditional Met transgenic mouse that mimicked human prostate cancer through an increased Met expression, which resulted in the oncogenic prostate transformation. Nevertheless, the presence of METamp and

PTEN deletion leads to prostate neoplasia and prostatic adenocarcinomas, inducing an epithelial-mesenchymal transition and an increase of metastasis events [

5]. As a result, METamp caused cell transformation; however, this had to take place in cooperation with another alteration in Met signaling pathways or MET parallel signaling co-activation, which could be needed to support the MET activities. All of these discoveries were the initial knowledge about

MET in cancer; nevertheless, the development of target therapies against active MET was not initiated until the discovery of

METex14, which is by far the most common driver and actionable

MET mutation.

2. MET in Cancer Initiation and Driver Mutations

2.1. MET Amplification

In 1996, Ichimura et al. revealed that MET protein and its specific ligand, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), were highly expressed in lung cancer cell lines, as well as in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) biopsies [

6,

7]. However, the protein levels did not reveal whether these results were associated with a specific

MET mutation or with the gene copy number gain (GCN) [

8], which could arise from polysomy or amplification. Still, the amplification represents a biologic selection process for

MET as an oncogenic driver. As

METamp has been recognized as a bad prognosis biomarker in NSCLC, HCC, gastric cancer, and triple-negative breast cancer [

9,

10,

11,

12], its identification in precision medicine through the GCN is currently calculated using the copy number variation (CNV) from next-generation sequencing (NGS) or using the standard assay fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [

13].

The current

METamp frequency in different solid cancers could be estimated thanks to the AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE), which is an international pan-cancer registry [

14]. According to GENIE,

METamp represents a 2% in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC 10,451 patients), a 1.2% in renal (1,556 patients), and hepatobiliary (1,854 patients) cancers, followed by a 0.4% in colorectal (7,370 patients), 0.2% in ovarian (4,481 patients), breast cancer (8,365 patients), and prostate cancers (3,530 patients). NSCLC has the highest

METamp and driver mutations frequency (

Table 1), as the

METex14 is the most common MET driver and actionable alteration [

15,

16]. Now, as much as

METamp and

METex14 are recognized as actionable because they account for different target therapies replacing the conventional chemotherapies; despite the success in

METamp, the therapy response will depend on the GCN degree.

2.2. MET Exon 14 Skipping Alterations

The

METex14 was first reported in small cell lung cancer and then in NSCLC patients. Furthermore, when

METex14 was expressed in normal mouse NIH3T3 fibroblasts, cells were transformed and then became tumorigenic in vivo, which confirmed

METex14 as a driver alteration [

17], whereas Paik and colleagues were demonstrating METex14 tumor cells were sensitive to MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), demostrating the clinical benefit for NSCLC patients [

18].

Normally, in

MET pre-mRNA, the introns flanking the exon 14 are spliced out, resulting in an mRNA containing exon 14, which encodes the juxtamembrane domain (JMD), which is key for MET protein degradation. The

METex14 causes the loss of JMD when mutations at the splice donor or acceptor sites result in exon 14 loss, such as base substitutions, insertions, deletions, and intronic noncoding regions immediately adjacent to the splice acceptor site and the whole-exon deletion. When some of these alternatives derived in a truncated MET receptor, it shows a constitutive expression because the loss of the Tyr1003 residue located in the JMD prevents the binding of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl and proteasomal degradation, which have shown overactive MET signaling pathways, triggering an exacerbate cell proliferation and invasion, contributing to the evolution of cancer and bad prognosis [

19,

20].

METex14 occurs in 3 to 4% of NSCLC patients (

Table 1), and it has been identified as a potent therapeutic target encouraging the approval of TKIs [

21,

22]. However, the actionability of different variants which originate the

METex14 alteration have not been totally validated yet. Currently, several

MET mutations are recognized as actionable METex14 by the approved test Foundation One (such as splice site 2888-10_2911del34, splice site 2888-37_2888-30delCGTCTTA, splice site 2888-18_2888-5del14, D1010N, splice site 3028+2T>C, splice site 2999_3028+4del34, splice site 3028+1G>A, and splice site 3028_3028+2delGGT), which were searched in the GENIE public database, and, as a result, only D1010N was found, representing 9.6% of 439

MET driver mutations (

Figure 1 and

Table S1). In addition, other frequent mutations recognized as a driver by GENIE impacting the exon 14 of

MET were found, as the X1010_splice (29%), followed by the X963_splice (20.9%) and D1010H (9.7%) (

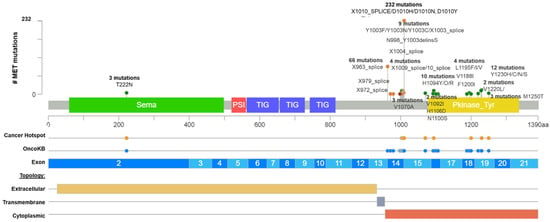

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Common MET driver mutations impact principally the juxtamembrane and kinase domains (exon 14). Lolliplot of MET protein domains (Sema, PSI, TIG, juxtamembrane, and Pkinase) showing common driver mutations identified in solid tumors from Table 1. Additionally, the protein structure shows the cancer hotspot (yellow circle), OncoKB prediction therapies (blue circles), exons numbered (blue and light blue rectangles), and protein topology. Yellow is the extracellular region, red, the cytoplasmic region, and, gray, the transmembrane region.

After that, we interrogate all these variants according to the bioinformatic driver predictors, and OncoKB as the actionability predictor, which is a precision oncology knowledge base developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center that contains biologic and oncogenic effects, prognostic, and predictive significance of somatic alterations [

23]. As is shown in

Table S1, sixteen alterations in exon 14 (affecting 374 patients) were recognized by different predictors, including OncoKB as oncogenic/likely oncogenic mutations with level 1 of evidence, which means these mutations concur with an FDA-approved drug. According to these results, many driver and actionable

MET mutations had not been functionally or clinically validated yet (

Table S1). Additionally, there is an extensive list of mutations in the

MET hot spot between exons 14 and 19 with drugs predictions, which must be evaluated as actionable alterations (

Figure 1 and

Table S1).

Still, the validation and approval of additional

MET driver alterations should be the next step to offer many potentially

METex14 targetable mutations [

24,

25]. Indeed, a study identified five hundred genetic alterations that lead to

METex14, and the analysis revealed that the most frequent regions impacted were the splice donor site (42%), followed by the polypyrimidine tract (15%), the splice acceptor site (~5%), and both the splice acceptor sites and the polypyrimidine tract (13%). All these alterations resulted in the elimination of exon 14 with an mRNA containing the exon 13 fused to exon 15 [

26].

Thereby, given the diversity of alterations leading to

METex14 revealed in mRNA, the diagnosis sensitivity could challenge the identification of them in DNA assays. In contrast, RNA approaches directly identify 13–15 exons fusion in the transcript. For this reason, the amplicon-based approaches may fail to find

METex14 alterations because it does not allow the detection of large deletions. However, hybrid capture is more amenable to detecting the alterations leading to

METex14. Furthermore, this method generally isolates larger fragments of DNA, including sequences that flank the regions of interest, compared with amplicon-based methods when using DNA as the input material [

27]. Additionally, 60% of positive results according to the RNA-based assay were negative using the DNA-based assay [

28]. Likewise, the mRNA-based quantitative reverse transcriptase RT-PCR demonstrated 100% sensitivity in detecting METex14, compared to 61.5% sensitivity using conventional DNA-based Sanger sequencing [

29], so RNA analysis seems to be best way to identify METex14 to follow with target drugs’ prescriptions.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms232213898