The Australian raven (Corvus coronoides) is a passerine bird in the genus Corvus native to much of southern and northeastern Australia. Measuring 46–53 centimetres (18–21 in) in length, it has all-black plumage, beak and mouth, as well as strong grey-black legs and feet. The upperparts are glossy, with a purple, blue, or green sheen, and its black feathers have grey bases. The Australian raven is distinguished from the Australian crow species by its throat hackles, which are prominent in adult birds. Older adult individuals have white irises, younger adults have white irises with an inner blue rim, while younger birds have dark brown irises until fifteen months of age, and hazel irises with an inner blue rim around each pupil until age two years and ten months. Nicholas Aylward Vigors and Thomas Horsfield described the Australian raven in 1827, its species name (coronoides) highlighting its similarity with the carrion crow (C. corone). Two subspecies are recognized, which differ slightly in calls and are quite divergent genetically. The preferred habitat is open woodland and transitional zones. It has adapted well to urban environments and is a common city bird in Sydney, Canberra, and Perth. An omnivorous and opportunistic feeder, it eats a wide variety of plant and animal material, as well as food waste from urban areas. In eastern Australia, its range is strongly correlated with the presence of sheep, and it has been blamed for killing lambs. However, this is very rare, and the raven most often scavenges for afterbirth and stillborn animals as well as newborn lamb faeces. The Australian raven is territorial, with pairs generally bonding for life. Breeding takes place between July and September, with almost no variation across its range. The nest is a bowl-shaped structure of sticks sited high in a tree, or occasionally in a man-made structure such as a windmill or other building. File:An audio recording of an Australian Raven (Corvus coronoides).wav

- newborn lamb

- carrion crow

- plant and animal

1. Taxonomy and Naming

The Australian raven was first described by Nicholas Aylward Vigors and Thomas Horsfield in 1827, when they reported George Caley's early notes on the species from the Sydney district.[1] Its specific epithet coronoides "crow-shaped" is derived from the Greek corone/κορόνη "crow" and eidos/είδος "shape" or "form".[2] The two naturalists regarded the Australian raven as very similar in appearance to the carrion crow (C. corone) of Europe,[3] though they noted it was larger with a longer bill. They did not give it a common name.[1] The location where the type specimen was collected is not recorded, but thought to be in the Parramatta district.[4] Christian Ludwig Brehm described Corvus affinis in 1845,[5] later determined to be this species.[6] In his 1865 Handbook to the Birds of Australia, John Gould recognised only one species of corvid in Australia, Corvus australis, which he called the white-eyed crow. He used Johann Friedrich Gmelin's 1788 name,[7] which predated Vigors and Horsfield's description.[8] In 1877 Richard Bowdler Sharpe recognised two species, but recorded that the feather bases of the type specimen of C. coronoides were white. He named C. coronoides as the "crow" and C. australis (as Corone australis) the "raven".[4] Scottish naturalist William Robert Ogilvie-Grant corrected this in 1912 after re-examining the type specimen, clarifying the species as C. coronoides (raven, and incorporating little and forest ravens) and C. cecilae (Torresian crow).[9]

Gregory Mathews described the western subspecies perplexus in 1912, naming it the southwestern crow and noting that it was smaller than the nominate subspecies. He called C. coronoides coronoides the eastern crow, listing its range as New South Wales, and described what is now the Australian crow as another subspecies, C. coronoides cecilae, calling it the north-western crow and recording its range as northwestern Australia. In the same work he listed the raven as Corvus marianae, with a type specimen from Gosford and listing its range as New South Wales. He listed the little raven and forest raven as subspecies.[10] Mathews had erected C. marianae in 1911 as the name after declaring Corvus australis Gould to be preoccupied;[11] French-American ornithologist Charles Vaurie acted as first reviser under Article 24 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) Code and discarded C. australis as a junior homonym—in 1788, Gmelin had used the same binomial name to describe the black nunbird—to preserve the stability of the name.[12] This has been followed by later authors.[13]

German ornithologist Erwin Stresemann lumped all Australian corvids plus other species as far as India into a single species, C. coronoides, as he believed there was intergradation between all characteristics such as iris colour, colour of feather bases and plumage. This was hotly disputed by Mathews. The official RAOU checklist listed three species (Australian raven, Torresian crow and little crow), with the little raven recognised as a fourth species in 1967 and forest raven in 1970. Stresemann described C. difficilis in 1943 from a single specimen, now thought to have been an unusual Australian raven or an Australian raven/Torresian crow hybrid.[4]

Alternative names sometimes seen include southern raven, southern crow and Kelly,[3] the last thought to have alluded to the Kelly Gang, though did not appear until the 1920s. Southern crow was considered by the RAOU before Australian raven was adopted as the official name for the species in 1926.[14] The term "crow" is colloquially applied to any or all species of Australian corvid.[4] The Australian raven was called wugan by the local Eora and Darug inhabitants of the Sydney Basin.[15]

1.1. Evolution and Systematics

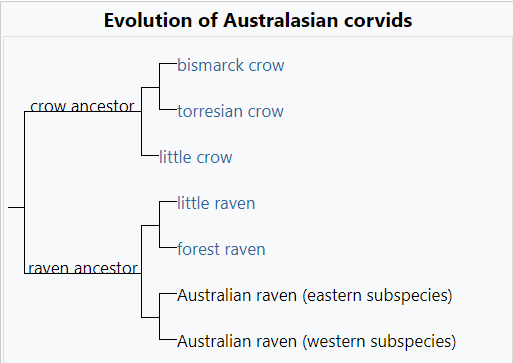

Phylogenetic tree based on Jønsson et al. 2012[16]

The Australian raven's closest relatives are the other two species of raven occurring in Australia: the little raven and forest raven. The Australian raven is also somewhat closely related to the Torresian and little crow, although not as closely related as it is to the other raven species. Initial single gene genetic analysis of the genus using mitochondrial DNA showed the three raven species to belong to one lineage and the two crows to another. The genetic separation between species is small and there was a suggestion the little raven may be nested within the Australian raven, though the authors conceded more genetic work was needed.[17] Subsequent multigene analysis using nuclear DNA by Jønsson and colleagues in 2012 showed the eastern and western subspecies of the Australian raven to form two clades, almost as genetically distinct as the forest and little raven are to each other. This led the authors to propose that the subspecies be recognised as separate species.[16]

Ian Rowley proposed that the common ancestor of the five species diverged into a tropical crow and temperate raven sometime after entering Australia from the north,[18] which molecular evidence indicates occurred in the early Pliocene epoch around 4 million years ago.[16] The raven diverged into the ancestor of the forest and little ravens in the east and Australian raven in the west,[18] this split occurring around 2 million years ago in the early Pleistocene.[16] As the climate became cooler and drier, the aridity of central Australia split them entirely. Furthermore, the eastern birds diverged into nomadic little ravens and, in forested refuges, forest ravens. As the climate eventually became warmer, the western birds spread eastwards and almost outcompeted forest ravens on mainland Australia. Rowley noted that the western subspecies of the Australian raven had features intermediate between the eastern subspecies of Australian and little ravens.[18]

Two subspecies are recognised:

- C. c. coronoides, the nominate or eastern subspecies, is found across most of eastern Australia.[3] Its range is also highly correlated with the presence of sheep. This is thought to be because of the frequency of dead animals, which can be an important source of food. Ornithologist Ian Rowley held that the eastern subspecies was expanding eastwards before European colonisation, and that this suggested it was of younger origin than the western subspecies, which appears static. The advent of agriculture facilitated further spread.[4]

- C. c. perplexus, the western subspecies, occurs from the head of the Great Australian Bight in South Australia westwards into Western Australia where its northern limits are Shark Bay and the mulga-eucalypt boundary line.[3] It is less specialised in its habitat, as it does not share its distribution with the little raven, and does not appear to correlate with the range of sheep.[4] The western subspecies has a slightly lower-pitched call than that of the eastern subspecies,[19] with similarities to calls of the little raven. Of smaller size overall, it has a more slender bill and shorter hackles. There is otherwise no difference in plumage.[20] Intermediate birds are found in the Eyre Peninsula, Gawler Ranges and vicinity of Lake Eyre in South Australia.[3]

2. Description

Adult in Sydney. Shows bare skin on neck. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1582979

Measuring 46–53 cm (18–21 in) in length with a 100 cm (39 in) wingspan and weighing around the 650 g (1.43 lb), the Australian raven is Australia's largest species of corvid.[3] The adult Australian raven is an all black-bird with a black beak, mouth and tongue and sturdy black or grey-black legs and feet.[21] The tibia is fully feathered and the tarsus is long, and the feet large and strong.[22] It has white irises.[21] The plumage is glossy with a blue-purple to a blue-green sheen, greenish over the ear coverts, depending on the light. The underparts are not glossy.[23] The Australian raven has throat feathers (hackles) that are lanceolate with rounded tips, while the other four species of Australian corvids have bifurcate tips, though this can be difficult to see in the field.[19] The hackles are also longer than those of the other four species; when they are raised (such as when the bird is calling), they give the bird an unusual bearded appearance. The upper third of the upper mandible, including the nares and nasal groove, is covered with bristles,[23] which can be up to 3 cm (1.2 in) long.[24] The heavy-set beak is tipped with a slight hook,[23] and is longer than the bird's head. The wings are long and broad, with the longest of its ten primary feathers (usually the seventh but occasionally the eighth) almost reaching the end of the tail when the bird is at rest. The tail is rounded or wedge-shaped.[22]

The Australian raven can be distinguished from the two species of crow occurring in Australia by the grey base of the feathers, which is white in the latter species. The demarcation between pale and black regions on the feather is gradual in the ravens and sharply delineated in the crows. Feather bases are not normally visible when observing birds in the field, but can sometimes be seen on a windy day if the feathers are ruffled.[19] Unlike the other four species, the Australian raven has a bare patch of skin under and extending to beside, the bill. This can be hard to discern in the field. The three species of raven are more heavily set with a broader chest than the two crow species, with the forest raven the stockiest of all.[25] Relative size of species is only useful when two species can be seen side by side, as the overlap in size is large and the difference in size small.[26]

Juveniles resemble adults, but lack throat hackles,[24] and sometimes have a pink fleshy gape.[27] The bill is shorter and shallower;[23] its base can be pinkish and the tip can be light grey.[21] The plumage is more ruffled and softer in appearance, lacks the glossy highlights and often having a brown tinge.[23] The bare skin on the throat is pink in birds that have recently left the nest.[21] Eye colour varies with age, gradually lightening from juvenile to adult.[23] Nestlings up to four months old have blue-grey irises, juveniles aged from four to fifteen months have dark brown irises, and immature birds have hazel irises with an inner blue rim around each pupil until age two years and ten months.[4][28] Immature birds older than one year develop hackles,[22] while some pink remains in the gape until the bird is two or three years of age.[21]

2.1. Vocalisations

The territorial call of the Australian raven is a slow, high ah-ah-aaaah (similar to the near-open front unrounded vowel (IPA:/æ/)) with the last note drawn out. It uses this call to communicate with other Australian ravens in the area.[29] When giving this call, the species has a horizontal posture, holding its head forward and body parallel to the ground, while perched on a prominent position. It ruffles its hackles and lowers its tail, and sometimes holds its beak open between calls. In contrast, the little raven and forest raven hold their bodies in an upright posture.[26] This call becomes louder if trespassers encroach upon the Australian raven's territory.[30] The five Australian species are very difficult to tell apart, with the call being the easiest way to do so,[3] although the drawing-out of the final note—long held to be solely recorded for the Australian raven—has been recorded for the other species and is hence not diagnostic.[26] File:A chatty Australian Raven.webm

The volume, pitch, tempo and order of notes can be changed depending on the message the Australian raven intends to convey. There is a variety of contact calls: a pair often makes a low murmuring sound when preening each other while roosting, and members of a flock carry on with a quiet chattering while at rest. Birds make a call and answer sequence if temporarily out of sight of one another while foraging. Birds in flocks make a single high-pitched caa while flying over another territory as a transit call to signify they are just passing through. An Australian raven will give a longer caa with a downward inflection to signify its return to the nest to its mate.[30]

3. Distribution and Habitat

The Australian raven is common throughout eastern Australia,[27] and southern Western Australia (the populations being connected by a narrow strip across the Nullarbor Plain), but it is rarer and more scattered in the north, with isolated sightings in Cape York at Coen, Windmill Creek and the Mitchell River,[31] and becoming more common south of Rockhampton in central Queensland. It is found throughout New South Wales, though is uncommon in the northeast of the state. It is rare in the Australian Alps, being replaced there by the little raven. It occurs across Victoria and eastern South Australia, through the Eyre Peninsula and Nullarbor Plain into Western Australia, across the state north to the Wooramel River.[32] It is found on some offshore islands such as Rottnest Island[33] and Kangaroo Island.[32] It is a rare vagrant to Lord Howe Island.,[32] though it was recorded as a vagrant in New Zealand in the 1870s, this has not been confirmed.

The Australian raven can be found in a wide range of natural and modified habitats. It requires available water and trees (or buildings) to roost in or perch on. Preferred habitats include eucalypt-dominated sclerophyll forest, and farmland adjacent to trees. It is also found in heath and mangroves. In areas where it occurs with the little raven, namely over much of central New South Wales, Victoria and into South Australia,[19] the Australian raven is restricted to more forested areas while the latter species prefers more open areas.[34] Similarly, in inland Australia it can share a range with the little crow, as the two do not appear to compete. However, the ranges of similar-sized forest raven and Torresian crow only narrowly overlap with the Australian raven as all three compete with each other. In central and western regions, Australian ravens and Torresian crows vie for the scattered uncommon trees and outcrops, and only one or the other are found there.[4] It co-occurs with the forest raven in northeastern New South Wales from Port Stephens northwards.[19] The Australian raven has adapted very well to human habitation in some cities and is the most common corvid in Canberra, Sydney and Perth; in Melbourne and Adelaide it is replaced by the little raven,[19] and by the Torresian crow in Brisbane.[35] Its large range, abundance and increasing population mean it is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[36]

4. Behaviour

Difficulties in distinguishing Australian corvids has hampered understanding of seasonal movements. The Australian raven is thought to be largely sedentary, with most movement of over 16 km (9.9 mi) due to flocks of non-breeding subadult birds.[37] Juvenile birds leave their parents and join flocks when they are four or five months old. Smaller flocks of 8–30 birds stay within an area of around 260 square kilometres, while larger flocks of up to 300 birds may travel hundreds of kilometres seeking food.[38]

A single breeding pair and their brood can occupy a territory of up to around 120 hectares (300 acres) and remains there year-round, though groups of ravens may enter this area to forage.[37] Australian ravens will defend their territory by chasing, dive-bombing and occasionally striking the backs of birds of prey, foxes or even people.[39] They generally mate for life, though occasionally one male has been found to be mated with two females in adjacent territories.[30] If the female dies, the male Australian raven maintains the territory and finds another mate, while if the male bird is lost, the female abandons the territory.[40] No courtship behaviour has been observed, and species that mate for life often lack elaborate courting displays.[30] Once they begin breeding at three years of age, they live another four to five years on average. During this time they produce two surviving young each year on average.[40] The longest-lived Australian raven recorded is an adult (of at least 3 years of age) that was banded and recaptured alive 12 years and 5 months later.[38]

Australian ravens generally walk when moving around on the ground, though do hop when hurrying. They preen themselves frequently, particularly when roosting in the middle of the day. They also engage in allopreening, where birds will preen each other's head and neck. This takes place particularly in autumn, winter and spring, and is important in pair bonding.[30] Either member may initiate it, generally by landing near the other bird, shuffling next to its mate, then bending its head forward and presenting its nape.[41]

4.1. Breeding

Australian ravens begin breeding once they are three years old.[40] Breeding season is from July to September,[42] with no substantial difference in timing across its range around the country despite it inhabiting a range of diverse climates and habitats across 19 degrees of latitude. Rowley has pointed out this is unusual for a bird species with a wide range and has postulated that breeding is initiated by day length. Rarely, breeding can take place in May, June or October.[43] Australian ravens generally nest in tall trees, never near to the ground as some species do.[31] The nest also functions as a lookout post and so tall or emergent trees are selected.[44] The ravens occasionally nest on buildings, telegraph poles,[31] or tall windmills which allow the species to occupy areas lacking in tall trees. Windmills may have assisted the spread of the species in North Queensland and the Northern Territory. The highest recorded corvid nest in Australia was found atop the AWA Tower in Sydney.[44]

Nests are generally large and untidy, consisting of a bowl or platform of sticks lined with grasses, barks, and feathers that can be up to 5 cm (2.0 in) thick.[45] As they are relatively heavy, they are built on larger forks in trees rather than out in the canopy. Building the nest is often time-consuming initially as the birds try (and often fail) to wedge sticks, which are 30–60 cm (12–24 in) long and 0.6–1.2 cm (1⁄4–1⁄2 in) thick, into the tree fork to make a platform. Thinner sticks and rootlets are used to make the bowl before the bowl is lined with feathers. Both birds build the nest, with the female taking over the lining of the nest while the male brings her material. New nests are built each year generally, as the re-use of old ones might spread disease or parasites—nests become caked with faeces as the nestlings grow and the parents cannot keep up with its removal. Furthermore, old nests often disintegrate within twelve months due to their exposed locations.[44] The female develops a brood patch—a patch of bare skin on the bird's underparts that reddens and becomes much more extensive from around three weeks before the first egg is laid. The skin itself is oedematous and wrinkled, and does not get re-feathered until December after the breeding season has finished.[43]

Their lofty locations makes monitoring of Australian raven nests difficult.[44] A clutch can comprise up to six eggs, though usually four or five are laid, with five being the most common number.[44] Measuring 45 by 30 mm (1 3⁄4 by 1 1⁄4 in), eggs are pale green or bluish-green and splotched with darker olive, brown and blackish markings.[42] Eggs are quite variable, and thus which Australian corvid laid them cannot be reliably identified.[44] Incubation of the eggs is done solely by the female over roughly 20 days. Incubation is intermittent initially, becoming constant by the time the third or fourth egg is laid.[45] Only one brood is raised per year, though a second clutch may be laid if the first clutch is lost early in the season. Late clutches have poor survival rates, possibly due to chicks getting dehydrated on hot days as the year progresses or being eaten by wedge-tailed eagles.[43] The chicks are altricial and nidicolous; that is, they are born helpless, naked and blind, and remain in the nest for an extended period.[45] They have pink skin until 5 days of age, when feathers under the skin turn it grey. They lose their egg tooth at the same time.[44] Their eyes begin opening at 5 to 6 days of age and are fully open by 11 to 12 days, by which time their feathers begin emerging. At 14 days, their primary feathers begin emerging, and they are fully feathered by 35–36 days old.[45] They leave the nest at 40–45 days of age, and stay with the parents for three to four months after that. They follow their parents and beg for food for the first month outside the nest but are feeding themselves by the third month. Young birds are often attacked when they enter neighbouring territories, and melees ensue as their parents try to defend them and herd them back.[44]

4.2. Feeding

The Australian raven is omnivorous, though eats more meat than smaller corvids. Its diet in summer contains a high proportion of insects, while more plant items are eaten in autumn. Flesh makes up over half its diet in winter. Invertebrates commonly eaten include spiders, millipedes, centipedes (which ravens behead before eating), grasshoppers, cicadas and caterpillars (especially of the family Noctuidae), which are important in feeding nestlings. Australian ravens sometimes eat yabbies (Cherax destructor) from the edges of dams. Unusually for a ground-feeding omnivore, earthworms are rarely eaten. Australian ravens have been reported killing birds of such size as young galahs (Eolophus roseicapillus) and starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Most mammals are eaten as carrion, as many species are too large for the raven to kill, though young rabbits are a frequent prey item.[46] Australian ravens drink water frequently, up to ten times a day in hot weather. Birds have been observed dunking pieces of meat in water before eating them,[30] as well as doing the same with hard biscuits to make them soggy and soft.[47]

Australian ravens are intelligent birds, and like many other corvids have innovative methods of seeking out food.[16] Foraging takes place in the early morning or late afternoon; birds rest in the hotter part of the day. Food is taken mainly from the ground, birds either finding objects while flying overhead or by walking along and looking.[30] However, they occasionally feed in trees—Australian ravens forage eucalypt foliage for Christmas beetles (Anoplognathus), and devote a substantial amount of time to look for nests and eggs to eat. They have also been known to take golf balls from fairways, possibly mistaking them for eggs.[46] Ravens use their bill rather than their feet to explore or turn items on the ground (rocks or sticks) over or hold or snatch food while flying. They have also been recorded using fence posts as anvils to bash snails against before eating them. Australian ravens most often eat food where they find it unless taking food back for nestlings. Occasionally they have been observed caching carrion or a killed animal in a hole nearby to store it. They can pack shredded meat in their mouth under their tongue.[30] Australian ravens have adapted well to eating food scraps in urban areas, such as school playgrounds, rubbish tips, bins outside supermarkets or restaurants, abattoirs, piggeries and farmyards.[31] In one isolated study, they were observed feeding on nectar from eucalypt flowers.[48] Australian ravens sometimes forage in mixed-species flocks with any of the other four species of Australian corvids. Sometimes they are aggressive with little ravens if both are at a food source and drive them off, though not if the smaller species greatly outnumber the larger.[49]

4.3. Parasites and Predators

A circovirus—given the name raven circovirus or RaCV—was isolated from an Australian raven suffering from feather lesions in 2006. It has affinities with canary circovirus (CaCV) and pigeon circovirus (PiCV). Its clinical significance is unknown.[50] Tick infestation is rare in the Australian raven, with Ixodes holocyclus and Amblyomma triguttatum recorded. Lice and hippoboscid flies have been recorded yet little-researched, and an infestation by the fly Passeromyia longicornis was recorded in one nest.[44]

The wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax) preys on adult, nestling, and fledgling Australian ravens, while the little eagle (Hieraaetus morphnoides) also takes nestlings, and powerful owl (Ninox strenua) has been recorded killing adults;[24] other birds of prey are seen as threats, yet there is no evidence they have successfully preyed on the ravens. The introduced red fox (Vulpes vulpes) competes with the Australian raven for carrion and can drive it off. It may also kill young birds that it catches on the ground.[44] The channel-billed cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae) has been recorded as a brood parasite.[24]

5. Relationship with Humans

Australian ravens sometimes die by being shot or poisoned—generally by farmers. Despite their fondness for roadkill, fewer ravens are hit by vehicles than Australian magpies. Research in the 1950s and 60s showed that 64% of Australian ravens perished in their first year of life. Immature birds are most at risk of dying.[38] The Australian raven is a peaceful bird, showing no aggression toward humans or other birds without reason. However, the Australian raven is frequently blamed for the loss of young lambs.[51] Scientific observation in the country's southeast showed that the killing of healthy lambs was rare, but that sick animals were predisposed to being attacked.[52] Australian ravens mostly eat faeces (often from the lamb's anus), afterbirth or stillborn lambs.[47][53] Newborn lamb faeces is nutritious, containing around 21–44% protein, 9–37% fat and 10–30% carbohydrate. It has the consistency of treacle and often sticks to the lamb's hindquarters or tail. The raven bites a sleeping lamb's tail, holding on and walking behind it when it wakes up. A healthy lamb would respond by running away or butting the bird, but a sick one might not respond and be attacked further as it alerts the bird that it is vulnerable. Wounded lambs can also succumb to Clostridium infection as these bacteria are present on raven bills.[52] Ravens bring some benefits to agricultural areas as they clean away carrion and eat insects that are potentially damaging to crops.[54] In areas of Western Australia, the species is classified as a Declared Pest of Agriculture under the provisions of the Agriculture and Related Resources Protection Act 1976, meaning that shooting on private land in rural areas is legal, although should be considered only after other options have been exhausted.[55]

5.1. In Indigenous Culture

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Crow is a trickster, culture hero and ancestral being. In the Kulin nation in central Victoria he was known as Waa (also Wahn or Waang) and was regarded as one of two moiety ancestors, the other being the more sombre eaglehawk Bunjil. Legends relating to Crow have been observed in various Aboriginal language groups and cultures across Australia.[56]

To the Noongar people of southwestern Australia, the Australian raven was Waardar, "the Watcher" and was wily and unpredictable. Noongar people were socially divided into two moieties or kinships: waardarng-maat and marrnetj-maat, or members of the Australian raven and long-billed corella (Cacatua tenuirostris) respectively.[57]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:Australian_raven

References

- Vigors, Nicholas Aylward; Horsfield, Thomas (1827). "A Description of the Australian Birds in the Collection of the Linnean Society; with an Attempt at Arranging them According to their Natural Affinities". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 15: 170–331 [261]. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1826.tb00115.x. https://zenodo.org/record/1447478.

- A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1980. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

- Higgins 2006, p. 690.

- Rowley, Ian (1970). "The Genus Corvus (Aves: Corvidae) in Australia". CSIRO Wildlife Research 15 (1): 27–71. doi:10.1071/CWR9700027. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9700027

- Brehm, Christian Ludwig (1845). "Das Stiftungsfest der naturforschenden Gesellschaft des Osterlandes in Altenburg, am 5 Julius 1843, und Etwas über die Vögel Griechenlands und Australiens" (in de). Isis 5: 323–58. http://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00191904/ISIS_1845_0169.tif.

- Australian Biological Resources Study (12 February 2010). "Species Corvus coronoides coronoides Vigors & Horsfield, 1827". Australian Faunal Directory. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Government. http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/abrs/online-resources/fauna/afd/taxa/515f8054-2e94-4023-9349-0d7221a6ce41;jsessionid=08C292899496F02DEF9D06BF42D75463.

- John Latham had described the south-seas raven in 1781, with loose throat feathers and being found in "the Friendly Isles" in the South Seas, but did not give it a binomial name.[7] The place is thought to be Tonga.[4] Gmelin gave it the name Corvus australis in the 13th edition of Systema naturae in 1788.[8]

- Gould, John (1865). Handbook to The birds of Australia. v.1. London: self. p. 475. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/8460042.

- Ogilvie-Grant, William Robert (1912). "The Crows of Australia". Emu 12 (1): 44–45. doi:10.1071/MU912044. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FMU912044

- Mathews, Gregory M. (1912). "A Reference-List to the Birds of Australia". Novitates Zoologicae 18: 171–455 [442]. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.1694. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/3110200.

- Mathews, Gregory M. (1911). "Alterations in the Nomenclature of "Handbook of the Birds of Australia"". Emu 10 (5): 317–26. doi:10.1071/MU910317. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FMU910317

- Vaurie, Charles (1962). Mayr, Ernst. ed. Check-list of Birds of the World (XV ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 261. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14485649.

- Schodde, Richard; Mason, I. J. (1999). Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO. p. 609. ISBN 978-0-643-10293-4.

- Alexander, W.B. (1933). "Popular Names for Australian Birds". Emu 33 (2): 110–11. doi:10.1071/MU933110. http://www.publish.csiro.au/?act=view_file&file_id=MU933110.pdf.

- Troy, Jakelin (1993). The Sydney language. Canberra, ACT: self-published. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-646-11015-8.

- Jønsson, Knud A.; Fabre, Pierre-Henri; Irestedt, Martin (2012). "Brains, tools, innovation and biogeography in crows and ravens". BMC Evolutionary Biology 12: 72. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-72. PMID 22642364. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3480872

- Haring, Elisabeth; Däubl, Barbara; Pinsker, Wilhelm; Kryukov, Alexey; Gamauf, Anita (2012). "Genetic divergences and intraspecific variation in corvids of the genus Corvus (Aves: Passeriformes: Corvidae) – a first survey based on museum specimens". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 50 (3): 230–46. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2012.00664.x. http://www.biosoil.ru/files/00010833.pdf.

- Rowley, Ian (1973). "The Comparative Ecology of Australian Corvids. VI. Why five species?". CSIRO Wildlife Research 18 (1): 157–69. doi:10.1071/CWR9730157. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9730157

- Higgins 2006, p. 692.

- Higgins 2006, p. 714.

- Higgins 2006, p. 712.

- Higgins 2006, p. 713.

- Higgins 2006, p. 691.

- Higgins 2006, p. 711.

- Higgins 2006, p. 693.

- Higgins 2006, p. 694.

- Birds in Backyards. "Australian Raven". http://birdsinbackyards.net/finder/display.cfm?id=26.

- Rowley and colleagues recorded iris colour changes of all five Australian corvid species raised in captivity.[4]

- Australian Museum Online. "Crows and Ravens". http://www.amonline.net.au/factSheets/crows_ravens.htm.

- Rowley, Ian (1973). "The Comparative Ecology of Australian Corvids. II. Social Organization and Behaviour". CSIRO Wildlife Research 18 (1): 25–65. doi:10.1071/CWR9730025. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9730025

- Higgins 2006, p. 696.

- Higgins 2006, p. 697.

- "Birds of Rottnest Island". Rottnest Island Authority. http://www.rottnestisland.com/about/flora-and-fauna/birds.

- Higgins 2006, p. 695.

- Birdlife Australia (2014). "Torresian Crow". Birds in Backyards. Birdlife Australia. http://www.birdsinbackyards.net/species/Corvus-orru.

- error

- Higgins 2006, p. 698.

- Higgins 2006, p. 699.

- Higgins 2006, p. 708.

- Rowley, Ian (1971). "Movements and longevity of ravens in south-eastern Australia". CSIRO Wildlife Research 16 (1): 49–72. doi:10.1071/CWR9710049. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9710049

- Higgins 2006, p. 707.

- Beruldsen, Gordon (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs. Kenmore Hills, Queensland: self. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-646-42798-0.

- Rowley, Ian; Braithwaite, L.W.; Chapman, Graeme S. (1973). "The Comparative Ecology of Australian Corvids. III. Breeding seasons". CSIRO Wildlife Research 18 (1): 67–90. doi:10.1071/CWR9730067. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9730067

- Rowley, Ian (1973). "The Comparative Ecology of Australian Corvids. IV. Nesting and the rearing of young to independence". CSIRO Wildlife Research 18 (1): 91–129. doi:10.1071/CWR9730091. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9730091

- Higgins 2006, p. 710.

- Rowley, Ian; Vestjens, W.J.M. (1973). "The Comparative Ecology of Australian Corvids. V. Food". CSIRO Wildlife Research 18 (1): 131–55. doi:10.1071/CWR9730131. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9730131

- Higgins 2006, p. 701.

- Richardson, K.C. (1988). "Are Australian Corvids Nectarivorous?". Emu 88 (2): 122–123. doi:10.1071/MU9880122. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FMU9880122

- Higgins 2006, p. 700.

- Stewart, Meredith E.; Perry, Ross; Raidal, Shane R. (2006). "Identification of a novel circovirus in Australian ravens (Corvus coronoides) with feather disease". Avian Pathology 35 (2): 86–92. doi:10.1080/03079450600597345. PMID 16595298. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F03079450600597345

- Temby, Ian. "Predatory Birds". http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/dpi/nreninf.nsf/childdocs/-C3270146B772814F4A2568B30006FFEE-7A5820241AEA1564CA256BC800078098-7B785784C934E20E4A256DEA00292002-75C7A9C8E202D918CA256BCF000B4D7C?open. (Subscription content?)

- Rowley, Ian (1969). "An evaluation of predation by 'crows' on young lambs". CSIRO Wildlife Research 14 (2): 153–79. doi:10.1071/CWR9690153. https://dx.doi.org/10.1071%2FCWR9690153

- Lambing takes place in late winter, with stillbirth rates around 20%, so there is a supply of carrion around farming areas.[47]

- Higgins 2006, p. 702.

- Department of Environment and Conservation (12 December 2007). "Fauna Note No. 16: Australian Raven". Department of Agriculture and Food website. Perth, Western Australia: West Australian Government. http://archive.agric.wa.gov.au/objtwr/imported_assets/content/pw/vp/bird/16_raven.pdf.

- Mudrooroo (1994). Aboriginal mythology: An A–Z Spanning the History of the Australian Aboriginal People from the Earliest Legends to the Present Day. London: Thorsons. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1-85538-306-7.

- von Brandenstein; Carl Georg (1977). "Aboriginal Ecological Order in the South-West of Australia – Meaning and Examples". Oceania 47 (3): 169–86. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1977.tb01286.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fj.1834-4461.1977.tb01286.x