One of the most studied concepts in almost all situations concerns “how people cope with stressful situations”. The study of coping is fundamental because researchers agree that coping can reduce or amplify the effects of negative events and conditions on emotional distress and well-being. As Skinner, Edge, Altman, and Sherwood’s comprehensive review of systems of coping shows, the fundamental problem in the study of coping is that it is not a specific behavior that can be explicitly observed; instead, it is an organizational construct incorporating numerous actions that individuals take to deal with stressful experiences. Scholars are usually interested in conceptualizing or measuring “ways of coping,” which are categories based on selected dimensions of coping which classify the ways people cope. The lack of consensus on dimensions of identified ways of coping is one of the main issues in the literature that hinders the progress of our understanding by making it impossible to compare results from different studies or aggregate them.

1. What Is Coping?

One of the most studied concepts in almost all situations concerns “how people cope with stressful situations”. The study of coping is fundamental because researchers agree that coping can reduce or amplify the effects of negative events and conditions on emotional distress and well-being

[1]. As Skinner, Edge, Altman, and Sherwood’s

[1] comprehensive review of systems of coping shows, the fundamental problem in the study of coping is that it is not a specific behavior that can be explicitly observed; instead, it is an organizational construct incorporating numerous actions that individuals take to deal with stressful experiences. Scholars are usually interested in conceptualizing or measuring “ways of coping,” which are categories based on selected dimensions of coping which classify the ways people cope

[1]. The lack of consensus on dimensions of identified ways of coping is one of the main issues in the literature that hinders the progress of the understanding by making it impossible to compare results from different studies or aggregate them

[1]. To overcome these and multiple other problems about lack of consensus about coping dimensions, categories, and mechanisms, Skinner et al. developed and suggested a comprehensive and exhaustive structure of coping in which categories are functionally homogenous (i.e., all ways of coping within a category serve the same set of functions) and distinct (i.e., categories are different based on the set of functions they serve).

The motivational conceptualization of coping formulated by Skinner et al.

[2] defines coping as action regulation in psychological stress, where action consists of behavior, emotion, and orientation. In other words, coping refers to the ways people “mobilize, manage, energize, guide, channel, and direct their behavior, emotion, and orientation in stressful circumstances, or how they fail to do so”. (p. 401). This theory assumes that coping is a “strategy of adaptation”

[1][3] to the social world and involves making compromises between total triumph over the environment and total surrender to it. By coping, individuals serve larger evolutionary functions, such as securing adequate information about the environment or escaping from a potentially dangerous transaction

[1].

Through multiple deductive and inductive studies (starting from the academic context of children), Skinner and their colleagues

[1][2][4] introduced a coherent set of categories of coping that connects the lowest level of analysis or “instances” of coping to the highest level or adaptive processes that intervene between stress and its psychological, social, and physiological outcomes

[1]. In other words, the hierarchical structure of coping connects the countless changing real-time responses that individuals use in dealing with specific stressful transactions, such as “I read everything I could find about it,” to strategies of adaptation, such as “continuing to secure adequate information about the environment”. Before delving into more details in describing this structure, researchers next introduce the gig work context and, finally, adapt this structure to the gig work context to see whether the same structure can be concluded from gig workers’ “ways of coping” or “coping strategies”.

2. The Hierarchical Structure of Coping

2.1. Basic Psychological Needs

Self-determination theory (SDT) argues that humans have the potential for growth, integration, and well-being while also being vulnerable to defensiveness, aggression, and ill-being

[5]. Within SDT, the nutriments for growth are specified using the concept of basic psychological need satisfaction

[6]. The set of these basic needs is very limited because any basic need candidate or specific desire should meet all of nine strict criteria (e.g., “felt need satisfaction and need frustration should predict the thriving and ill-being of all individuals, regardless of differences in socio-demographics, personality, cultural background or need strength”; see

[5] (p. 4) for full reference) to be assigned the more formal status of a basic psychological need

[7]. In a brief sense, regarding basic psychological needs, “satisfaction is not only conducive to, but essential for individuals’ well-being, while its frustration increases the risk for passivity, ill-being, and defensiveness”.

[5][7][8] (p. 1).

The current list of these needs consists of the need for autonomy or experiencing volition and willingness; relatedness or experiencing warmth, bonding, and care from significant others; and competence or experiencing mastery and ability to cause desired outcomes

[7][9][10][11][12]. The satisfaction of basic psychological needs represents individuals’ psychological, energetic resources, and as such, stimulates individuals’ well-being and performance, whereas thwarting those needs has an energy-depleting effect, leading to lower performance and well-being

[6][13][14]. This premise has been tested by various studies in different cultures and life domains and across different occupations, providing support for the relationship between basic needs and burnout

[6][15][16][17].

The hierarchical structure of coping is based on a motivational action theory of coping that argues that three classes of concerns related to individuals’ basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) trigger organized biobehavioral responses or “families of coping”

[1][2][4]. In line with SDT, it can be categorized adaptive processes as efforts to adapt to the loss of each need as adaptive processes that (a) coordinate actions with the contingencies in the environment (concerned competence), (b) coordinate reliance on others with the social resources in the environment (concerned relatedness), and (c) coordinate preferences with the options available (concerned autonomy) in the environment.

Rockmann and Ballinger

[18] tested the main premise of SDT for the highly skilled, on-demand work context, and found that to the extent that on-demand work fulfills one’s basic psychological needs, workers will develop intrinsic motivation

[19][20]. Jabagi et al.’s

[19] nuanced literature review on how basic psychological needs are facilitated or impaired in platform work included a wide range of platforms and integrated the job characteristics model and enterprise social media research concerning SDT to suggest that platform organizations can motivate workers by the thoughtful design of their digital labor platforms and the integration of social media technology.

2.2. Adaptational Processes

Species face multiple fundamental adaptational problems that need to be addressed for their survival

[1][3], and internal or external threats to well-being are some of those issues

[3]. Coping, as one adaptive solution, includes “a complex psychobiological reaction that fuses intelligence with motivational patterns, action impulses, and physiological changes that signify to both the actor and observer that something of significance for well-being is at stake in the encounter with the environment”

[3] (p. 615). A person-environment relationship involving a particular kind of harm or benefit generates action tendencies relevant to the specific conditions of harm or benefit and stimulates (motivates) the organism to behave in ways that enhance its potential to survive and flourish.

2.3. Families of Coping

The hierarchical structure consists of two intermediate levels. Lower-order categories or “ways of coping” are categories that classify “instances of coping” (items or observations) into mutually exclusive categories (e.g., problem-solving, rumination). Higher-order categories are “families of coping” that classify ways of coping according to their adaptive functions. Each family of coping is organized around (1) whether the concern is appraised as a challenge versus a threat and (2) whether the ways of coping are targeted at oneself or one’s context. The criteria for family membership are behaviors, emotions, and orientations that each pattern of appraisal triggers. For instance, an appraisal of a “challenge for autonomy” will be accompanied by an “Accommodation” or a “Negotiation” coping family. Still, if the level of stress related to the concern increases such that it becomes appraised as a “threat to autonomy,” it will be accompanied by “submission” and “opposition,” depending on whether a person decides to target the self or the context. The result is higher-order families of coping organized around three basic psychological needs, two appraisals of challenge vs. threat

[21], and two coping targets of self and context. These families of coping will be illustrated in detail in the next section, through the radar representation of this hierarchical structure.

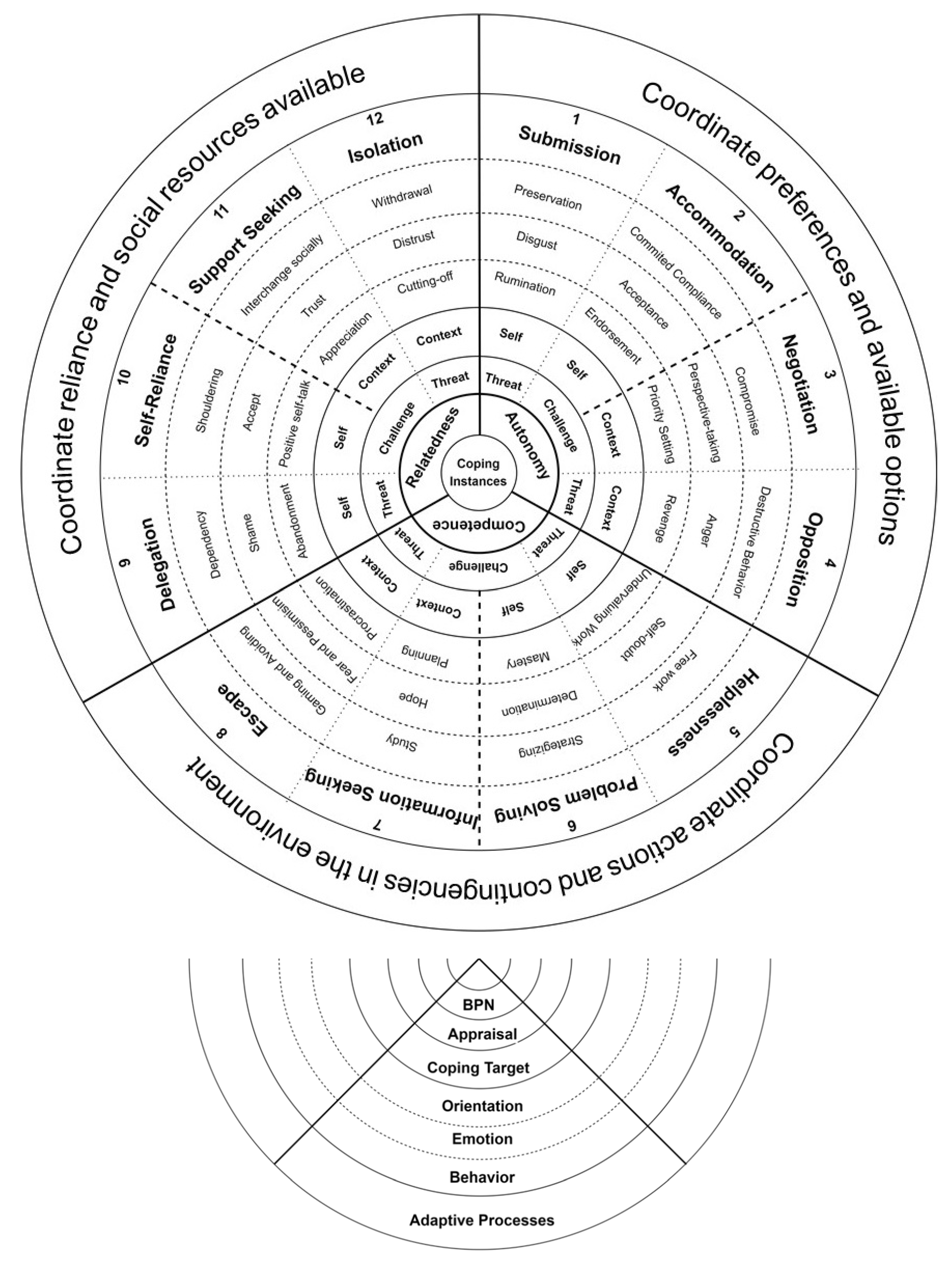

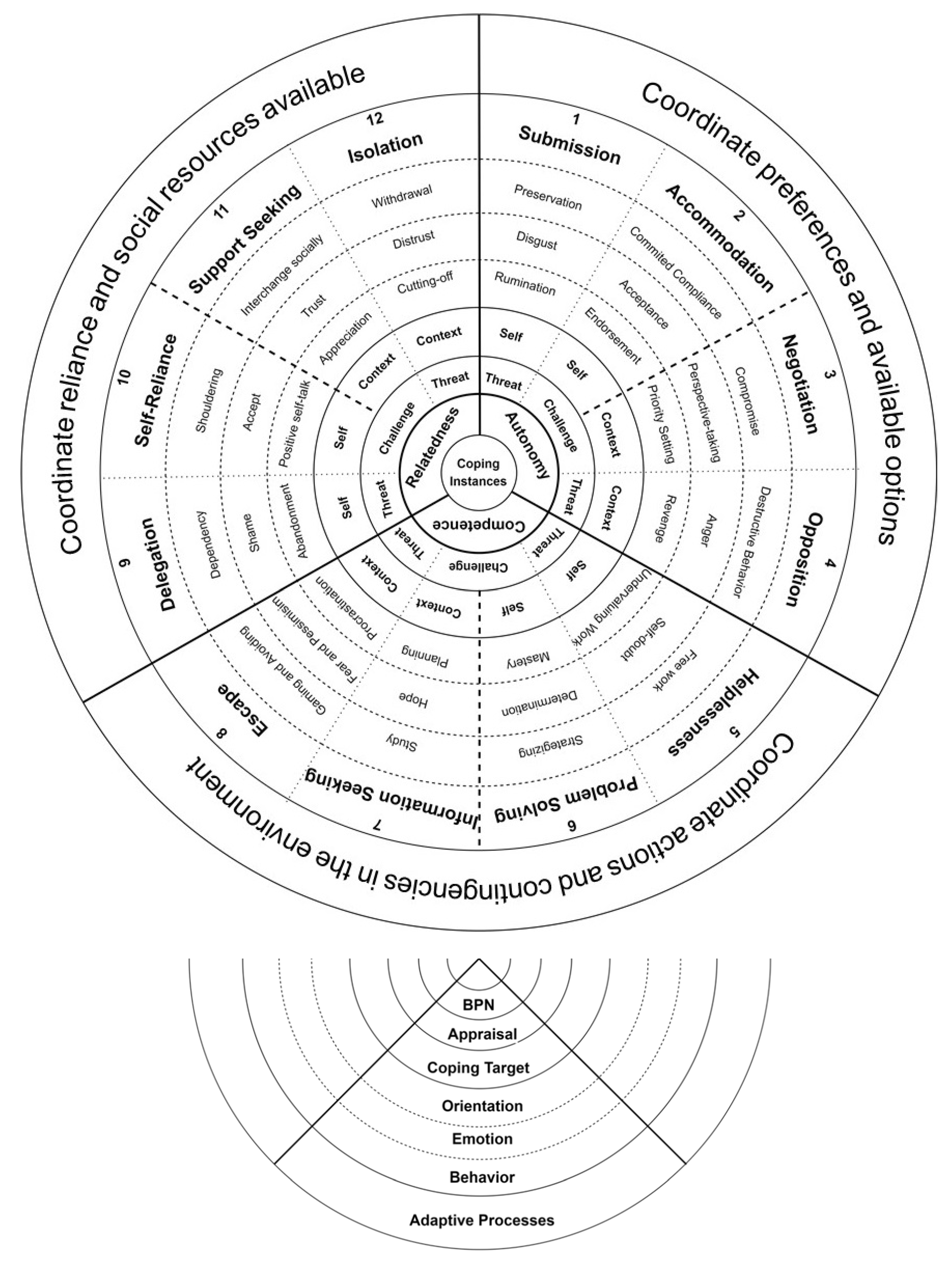

Figure 1. A radar view of 12 families of coping in gig work and a corresponding reading guide based on multiple dimensions of coping involved. Note: BPN = basic psychological needs.

Researchers believe a radar arrangement of the dimensions of coping makes it easier to understand, remember, and interpret. Researchers proposed radar of copings in gig work includes 12 families of coping identified based on (a) three basic psychological needs, (b) two appraisals of challenges or threats, and (c) two targets, self or context. These 12 families of coping connect first-order instances of coping to higher-order adaptive processes of coping, and each involves a set of related behaviors, emotions, and orientation, and they are arranged in three sets of four. The radar is designed to highlight the critical roles of three basic psychological needs and constructive coping families, those that are triggered as “challenge” appraisals of contextual factors. These coping families are highlighted in the framework. In the radar, the first set involves concerns for autonomy and is triggered when workers feel pressured to act against their will. The second set of coping families involves concerns about the competence and is triggered when workers perceive a lack of information to predict work outcomes in the context. The third set of four involves challenges and threats to relatedness and is triggered when workers feel that they are not trusted or cannot trust important others.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph192114219