Thanks to recent advances in analytical technologies and statistical capabilities, the application field of metabolomics has increased significantly. Currently, this approach is used to investigate biological substrates looking for metabolic profile alterations, diseases markers, and drug effects. Due to the low work-up required, high data reproducibility, and high throughput, NMR spectroscopy is an optimal detection technique in metabolomics studies. The use of NMR-based metabolomic approaches in the investigation of a metal drug action mechanism or for assessing tumour response to anticancer metal agents is a recent, fast-growing tool. Only in recent years has the NMR-based metabolomic approach been extended to investigate the cell metabolic alterations induced by metal-based antitumor drug administration. The future perspectives are even more interesting. The use of a metabolomics approach was very effective in assessing tumor response to drugs and providing insights into the mechanism of action and resistance. Therefore, metabolomics may open new perspectives into the development of metal-based drugs. In particular, it has been shown that NMR-based in vitro metabolomics is a powerful tool for detecting variations of the cell metabolites induced by the metal drug exposure, thus offering also the possibility of identifying specific markers for in vivo monitoring of tumor responsiveness to anticancer treatments. Moreover, NMR-based metabolomics could also play an important role in clinical trials, preventing or reducing unwanted side effects of metal anticancer drugs by the early detection of metabolic dysfunctions in bio-fluids.

- metabolomic

- 1H NMR Spectroscopy

- antitumour drugs

- metal drugs

- platinum drugs

1. Introduction

In international scientific researches, the term “Omic” started to be used in the 1990s, when the Human Genome Project, whose aim was to determine the DNA nucleobases’ sequences, was launched, in order to identify and map genes of the human genome (the “genomics” research field) [1]. The growth of scientific knowledge and the development of new technologies increased the need to further delimit and define the fields of related research, mainly focusing on the detection of mRNA (transcriptomics), proteins (proteomics), and metabolites (metabolomics) in specific biological samples [2].

These research strategies resulted in many applications and still have much potential. In fact, Omics technologies can be applied, not only for the understanding of biological systems in a normal physiological state, but also to get insight for specific disease conditions. Indeed, these technologies can play a determinant role in screening, diagnosis, and prognosis, as well as in the understanding of diseases etiology [2].

“Metabolomics” is the latest Omics technology. Like the other Omics sciences (such as genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics), metabolomics uses analytical technologies that allow the production of large amounts of information (big data). In the specific case of metabolomics, the analytical techniques are normally used to identify, characterize, and quantify small biological molecules that are involved in the structure, function, and dynamics of cells, tissues, or organisms [3]. In this respect, different from the others Omics sciences, which can only describe what might happen to a biological system in the future, metabolomics gives information about what happened in the considered system and producing the observed metabolites, thereby getting direct insight about the physiological status of the studied organism [4].

The importance of metabolic profiling of bio-fluids was recognized, for the first time, in the late 1990s with the introduction of the term “metabonomic”. This was last used to describe the quantitative measure of the metabolic, multi-parametric, and time-correlated response that a living system gives to a (patho) physiological stimuli or to genetic modifications [5]. Instead, the later definition of “metabolomics” consists of the identification and quantification of all the main low-molecular-weight metabolites/intermediates that vary according to the physiological or pathological state of the cell, tissue, organ, or organism of a biological system [6,7,8,9]. However, although some confusion has crept into the field, the difference in the use of metabolomics and metabonomics over the recent years has been clearly described [10], and nowadays the two terms are often used interchangeably [11].

Metabolomic science was born with the important aims of (among others) population profiling (for identifying metabolome-wide associations and novel risk biomarkers), food material profiling (for identify origin and for a quality control), and individual profiling (for a personalized health care). Nevertheless, it is also currently used for studying the mechanism of drug toxicity/efficiency and to develop new drugs [12]. On the other hand, there are some limitations related to the use of the technique, mainly due to biological variance and environmental influence, the difficulty of measuring minor (low-concentration) metabolites and the complexity of the resulting data sets. Despite these limitations, there are many advantages in using a metabolomic approach. First of all, there is the lack of need for analyte pre-selection, but also the achievable robustness and stability of analytical platforms [10].

It is important to consider that metabolomics generally consist of the use of separation (Gas Chromatography, GC, Capillary Electrophoresis, CE, High Performance Liquid Chromatography, HPLC, Ultra High Performance Liquid Cromatography, UPLC) and detection techniques (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, NMR, and Mass Spectrometry, MS). Traditional methods require separation and optimization of the separation condition each time, followed by identification. Often, multiple slow separations (up to 72 h per sample) are necessary, and intensive manual work is needed, in addition to constant supervision and high-level skills [7,10]. In this context, the use of NMR spectroscopy in metabolomics studies has been given high throughput, thanks to the potential of this specific technique. Firstly, there is the advantage of measuring multiple (10 to 100) metabolites at once, with no need of their physical separation and a very limited sample working up. Secondly, this technique is non-destructive, and can be quantitative (different from MS) but capable at the same time, to allow metabolic profiles or “fingerprint” collection of the examined biological samples.

Due to the recent strong improvements of NMR technique and technologies, the NMR-based metabolomic is becoming a fast-growing and powerful technology [7]. Such improvements are essentially related to more reliable spectrometers, especially highly-sensitive NMR probes, with versatile acquisition sequences that can allow faster performance and substantial NMR experiments. Both the development of powerful databases of metabolic data and efficient multivariate statistical methods have simplified the high complexity (number of spectra, number of groups, number of condition) of big data set handling. Nowadays, all these aspects have made NMR-based metabolic profiling an unbiased tool that can provide fully quantitative data for most of the components in a complex mixture [7].

2. NMR Metabolomics in Cancer

One of the biggest areas of metabolomic research has been the discovery of metabolic biomarkers and biopatterns testifying to alterations due to cancer [4]. Cancer is, in fact, a fatal malignancy worldwide, as reported in the results of the Global Cancer Statistics of the International Agency for Cancer Research (IARC). In 2018, 18.1 million new cancer cases were estimated worldwide, as well as about 10 million deaths, over a half of cancer patients. These estimated data fully justify the close attention of researchers for improved technologies, allowing not only studies on cancer progression, but also the discovery of new biomarkers for a rapid and early diagnosis [13].

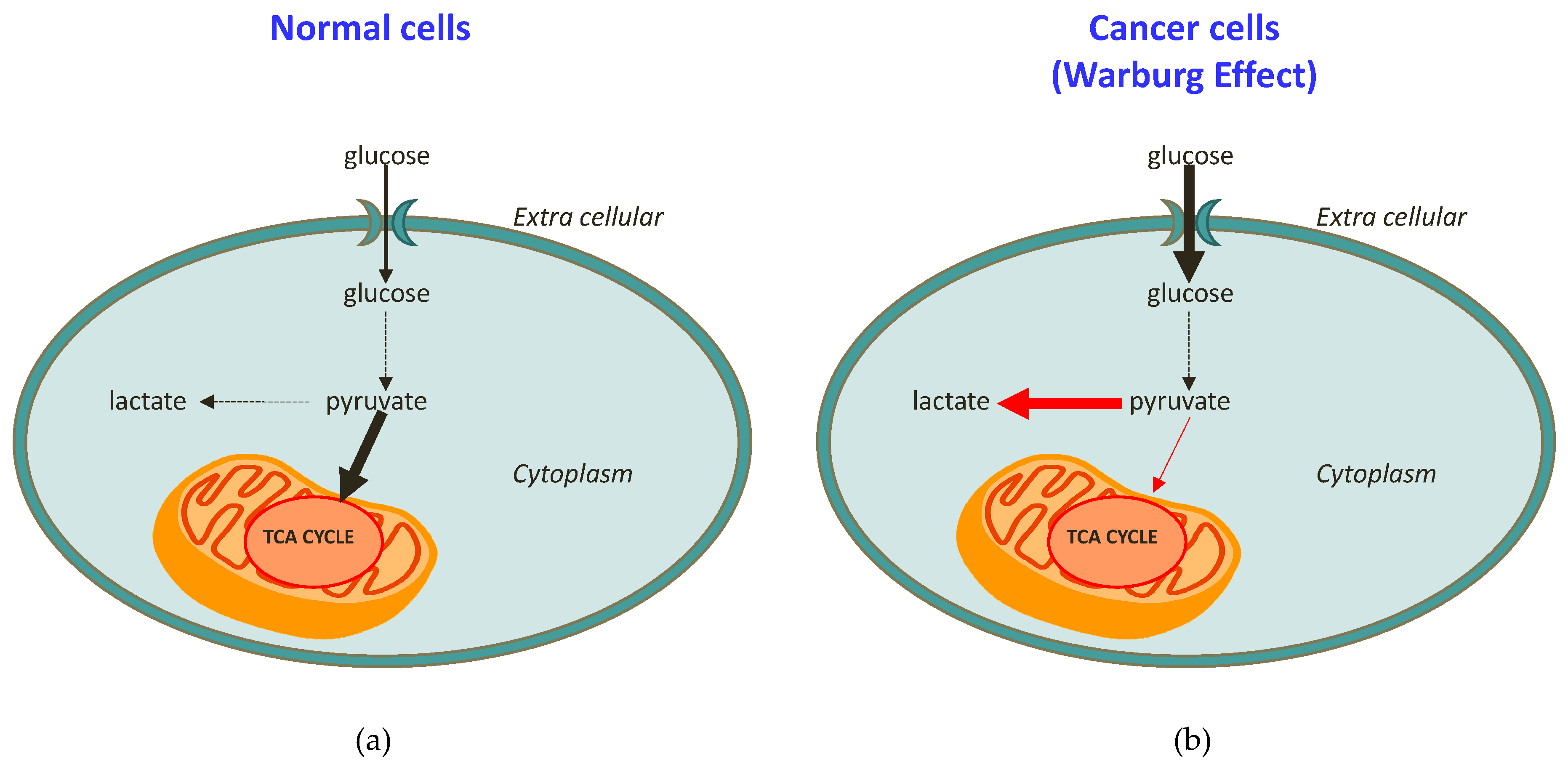

At this regard, it was demonstrated that a hallmark of cancer is represented by a reprogrammed metabolism. This was reported for the first time in the 1920s, thanks to the pivotal research of Otto Warburg showing that the metabolic patterns of cancer cells are generally different from those of normal cells [14]. In brief, normal cells use mitochondria to oxidise glucose and convert glucose into lactate only under hypoxia conditions (Figure 1a). In contrast, cancer cells avidly consume glucose, even in the presence of oxygen, and this is strictly associated with a lactate production increase (and then excretion; Figure 1b), together with the consequent acidic pH of cancer cells [14,15,16]. This discovery, at that time defined as “the root cause of cancer”, and subsequently simply indicated as “the Warburg effect”, won him the Nobel Prize for Medicine [15,16]. By increasing knowledge and scientific research, it was therefore proved that the Warburg effect cannot really be considered “the root cause of cancer”, today known to be determined by a combination of genetic and environmental triggering factors [17]. Nevertheless, the Warburg effect clearly describes how cellular respiration enzymes act in tumour cells, thereby opening new perspectives in the study of cancer [18]. In addition to the better understanding of cancer cells’ physiology, some studies are specifically designed to “reverse the Warburg effect” [19]. This last approach is also believed to be a valid method for pharmacologically acting against cancer. Indeed, several works have targeted the increased glycolysis, with the aim of inhibiting lactate production and excretion [19,20,21,22,23], and have found some success in preclinical models [24,25,26].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of (a) healthy cell metabolism in comparison to (b) cancer cell metabolism (the Warburg effect).

The Warburg effect has been confirmed in a variety of tumor types, including colorectal, breast, ovarian, lung, and glioblastoma cancers [14,18,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Furthermore, many studies have demonstrated that cancer cells are also dependent on fatty acid synthesis and glutaminolysis for proliferation [33]. All these differences with respect to normal cells suggest that targeting metabolic dependence could be a selective approach to treat cancer patients [27].

In this context, NMR spectroscopy, including in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and high-resolution magic angle spinning (HR-MAS NMR) analysis of tissue extracts, has been widely used to distinguish between different cell lines and tumor types [34]. As nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy is a high-throughput technology, it can be used to profile systemic metabolism in tumor diagnosis and prognosis [34]. NMR-based metabolomics have also been used to identify biomarkers for cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), colon cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, and others [4,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. The aims of the studies have been to shorten the time to diagnosis, especially in cancers for which early detection and screening are difficult but would significantly affect therapeutic treatment decisions, as well as prognosis.

NMR metabolomics studies of cancer are applied to different kind of samples, such as bio-fluids (e.g., urine, whole blood, serum, plasma) and tissue/cell extracts (e.g., liver, brain, or kidney). Samples are normally examined directly, without extensive sample preparation, so that beside in vivo and in situ, a huge number of bio-fluids information are easily obtained [4,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

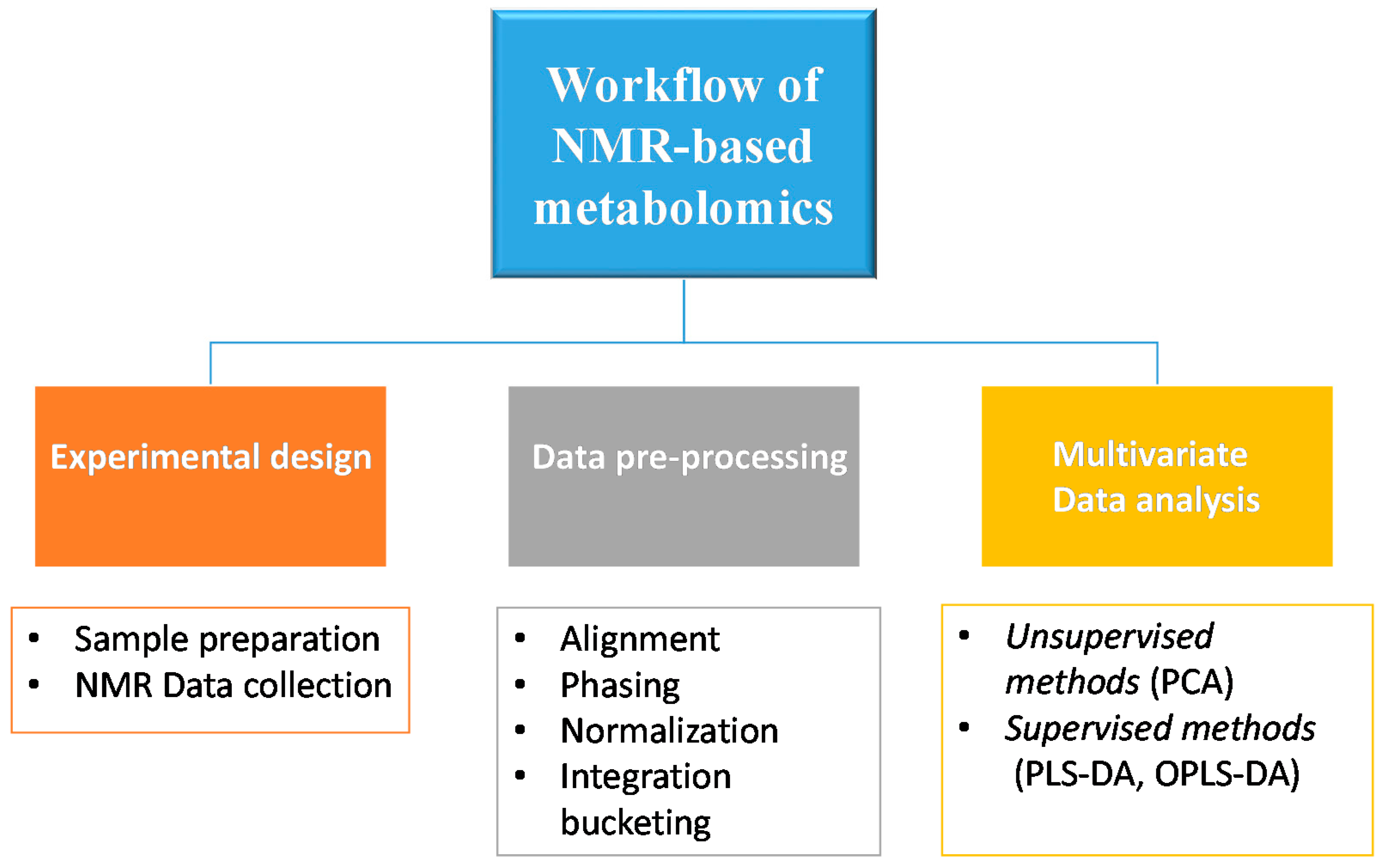

The basic workflow of an NMR-based metabolomic approach starts with experimental design, including the evaluation of appropriate sample numbers to yield informative and statistically significant results, as well as biological and analytical experiments, such as sample preparation and NMR data acquisition. After this, the data preprocessing phase and subsequent data analysis follow. Then the metabolomics study requires the interpretation of the results using a multivariate data analysis, which usually consists of unsupervised and supervised methods (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the basic workflow of NMR-based metabolomics.

3. Multivariate Data Analysis

4. The Potential of an NMR Metabolomics Approach in Monitoring the Response to Metal-Based Antitumor Drugs

The development of a new drug is a fundamental step in medicine. It consists in identifying a general therapeutic area of interest, a specific disease to treat, and in most cases, the biological “target” [57]. In the past, the lack of complete knowledge of the action mechanism for a specific drug often resulted in the failure of clinical trials, as in the well-known case of Dimebon, a drug studied for Alzheimer’s [58]. In fact, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the U.S. government agency responsible for regulating food and pharmaceutical use, does not require any specific understanding about the drugs’ mechanism of action before starting clinical trials. Nevertheless, the last aspect is an essential step in the development of a new drug, because a clear understanding of the altered metabolic pathways due to a pharmacological treatment, as well as the action mechanism of a drug before it enters clinical trials, may prevent a late-stage failure [57]. A good strategy to detect treatment-related altered metabolic pathways is the monitoring of changes in the metabolome following the starting of chemotherapeutic treatment [59]. Indeed, the response to chemotherapy is often known to induce several metabolic alterations with respect to the physiological condition [59].

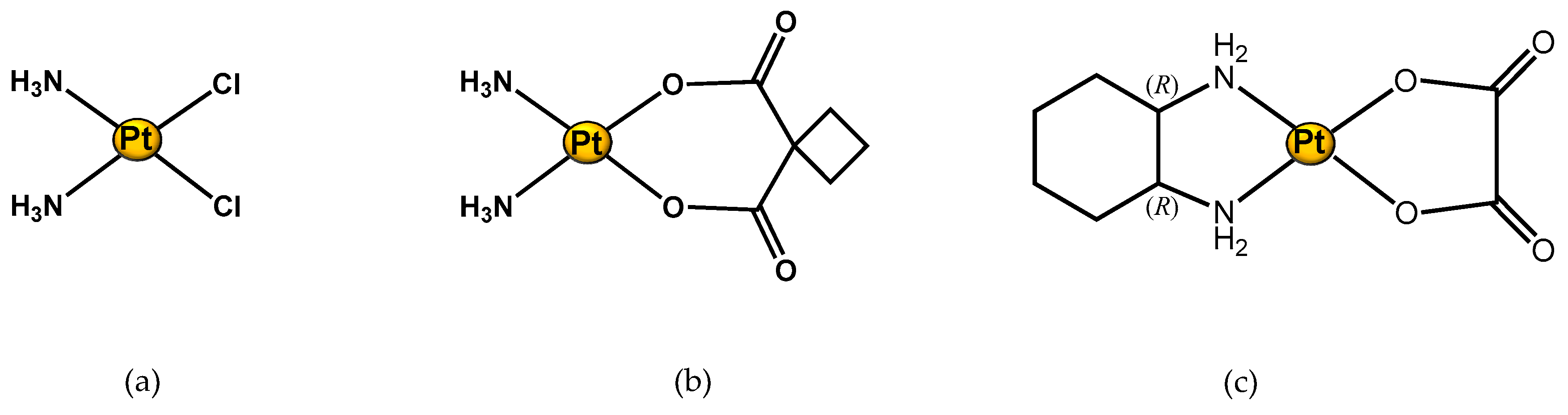

One of the most widely used anticancer drugs is cisplatin, a metal-based drug that acts by binding to genomic DNA targets. The discovery of cisplatin, a Pt(II) compound, by Barnett Rosenberg in 1960 represents a milestone in the history of metal-based compounds in the treatment of cancer [60]. Currently, cisplatin is used for the clinical management of patients affected by testicular, ovarian, head and neck, colorectal, bladder, and lung cancers.

Recently, many more metal-based compounds have been synthesized, either by redesigning the cisplatin chemical structure through ligand substitution, or by building completely new metal-based compounds. Therefore, regarding to pre-established structure−activity relationships (SARs), many unconventional Pt(II) and Pt(IV) compounds have been tested [61]. Nevertheless, other anticancer metal complexes—for example, complexes containing ruthenium (Ru(II) and Ru(III)) [62,63]), titanium (Ti(IV)), and gold (Au(I) and Au(III))—have been studied [64]. In particular, Palladium (Pd) compounds have drawn particular attention, due to its similarity to Pt(II) (electronic structure and coordination chemistry) in showing favourable cytotoxic activity, despite both of their high lability [65,66,67]. Involved studies have essentially developed new metal-based drugs with the aim of enhanced safety and cytotoxic profiles, but also to overcome the resistance phenomena observed for cisplatin [68].

The use of NMR-based metabolomic approaches in the study of metal-based anticancer drugs is very new. Indeed, few papers, and only in recent years, have dealt with the use of this tool by studying the response of biological systems (biofluids, cells, and tissue) to metal-based drugs treatment in vitro and in vivo. This work covers the state-of-the-art survey of the NMR-based metabolomics approach adopted in metal-based drugs research, focusing on the possible applications and advantages of this investigation approach.

4.1. NMR Metabolomics Studies of FDA-Approved Metal Complexes

As expected, cisplatin is the first metal-drug studied by using an NMR metabolomic approach (see Figure 3a). Different samples, such as biofluids (urine, serum), and different cancer cell lines were examined in order to investigate cisplatin-induced metabolic alteration under different conditions of treatment, and in different tumour types. In particular, one of the interest topics of these scientific studies has been cisplatin-induced side effects.

Figure 3. Structure of Pt(II) complexes studied through an 1H NMR metabolomic approach. (a) Cisplatin; (b) Carboplatin; and (c) Oxaliplatin.

4.2. NMR Metabolomic Studies of New Metal Complexes

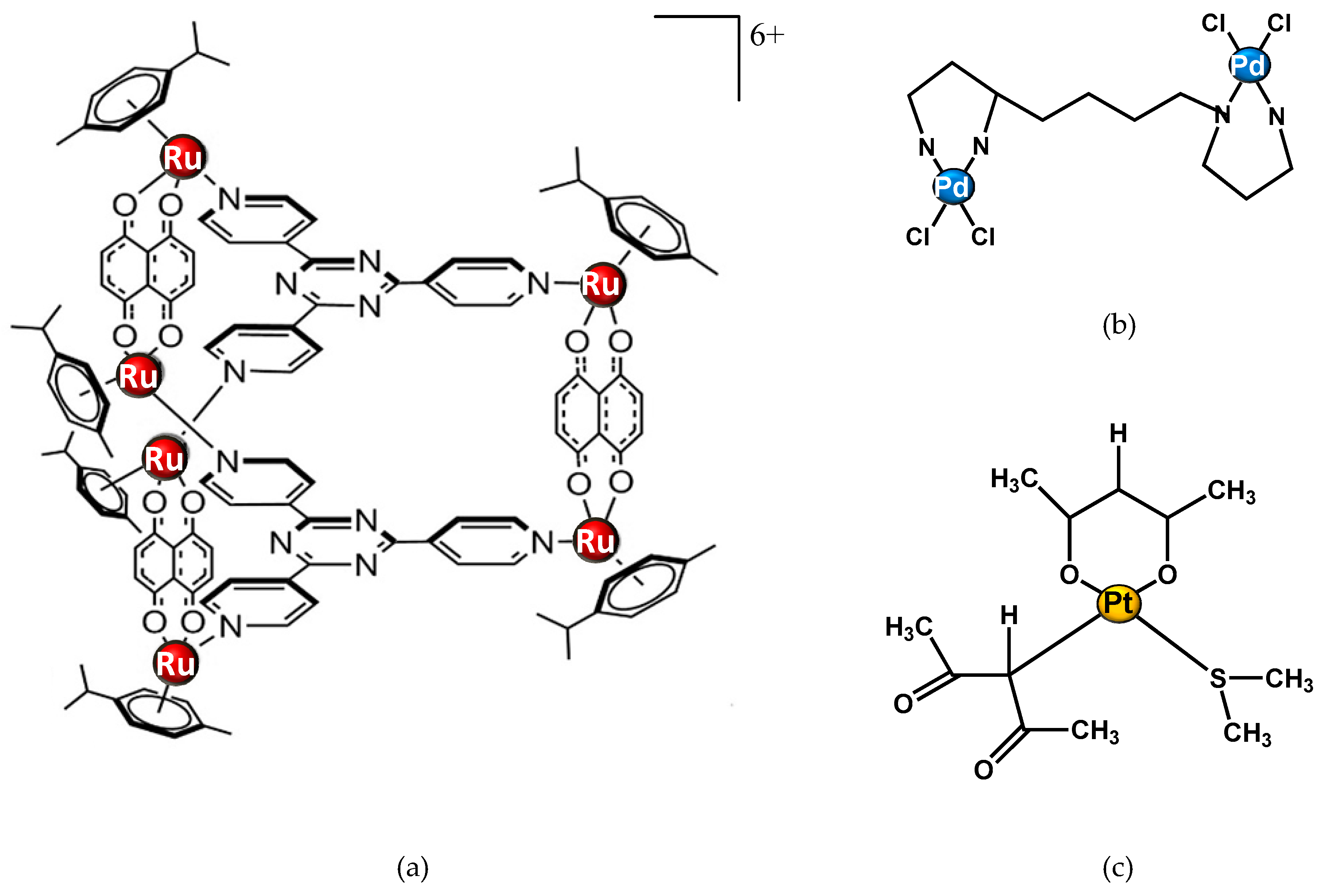

Through the NMR-metabolomics investigation of the effects of approved and widely used metal drugs (such as cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin), this new field helps to discover how a new metal drug acts in a biological system, and how to define the specific target of the drug. An example is the study of Vermathen et al. on a new ruthenium complex. They used this technique to profile cells in response to treatment with a hexacationic ruthenium metallaprism (Figure 4a) in three different cell lines: A2780 (human ovarian cancer cells), A2780cisR (cisplatin resistant cells), and HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney cells). This research revealed a different response depending both on the cell type and incubation time. The observed different metabolic profile is mainly due to changes in level expression of lipids, choline-containing compounds, glutamate and glutathione, nucleotide sugars, lactate, and some amino acids. The time-dependent metabolic response patterns suggest that A2780 cells on the one hand, and HEK-293 and A2780cisR cells on the other, may follow different cell-death pathways and exist in different temporal stages thereof [77].

Figure 4. Structure of metal complexes different from cisplatin and studied through 1H NMR metabolomic approaches. (a) Ruthenium metallaprism; (b) Pd2spermine; (c) [Pt(O,O’-acac)(γ-acac)(DMS)], Ptac2S.

Other NMR-metabolomics studies have focused on Palladium (Pd) compounds. Iamego et al. describes metabolomic studies of a Pd2Spermine (Pd2Spm) complex (Figure 4b) on osteosarcoma MG-63 and osteoblastic HOb cells. The aim of their work was to assess the impact of the potential palladium drug on cell metabolism in comparison with cisplatin.These findings open promising perspectives related to the impact of Pd2Spm on osteosarcoma cellular metabolism, particularly in drug combination protocols. [1]

NMR metabolomics can be applied also in the study of drug treatment resistance. Recently, De Castro et al. reported an 1H-NMR-based metabolomic study to evaluate the response of a cisplatin-resistant epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line, SKOV-3, to a new promising Pt(II) drug, [Pt(O,O′-acac)(γ-acac)(DMS)], or Ptac2S (Figure 4c). The SKOV-3 cells’ metabolic behaviour after the Ptac2S treatment suggests a possible “reversal of the Warburg effect” through the inhibition of lactate synthesis (probably due to a modulation of the lactate dehydrogenase activity). Furthermore, the different lipidic profile in Ptac2S, with respect to cisplatin-treated cells, indicates a possible cell death mechanism different from apoptosis (the known cisplatin-induced mechanism of death) [2]. These findings parallel the results derived through the NMR metabolomic analysis, confirming the power of the technique in the investigation of mechanisms of action.

In conclusion, NMR-based metabolomics appears very promising in metal-based drug research specially in order to study metal drug-induced side effects, treatment response prediction (thus also eventually resistance), and action mechanism key information for known and new compounds.

References

- Inês Lamego; M. Paula M. Marques; Iola F. Duarte; Ana S. Martins; Helena Oliveira; Ana M. Gil; Impact of the Pd 2 Spermine Chelate on Osteosarcoma Metabolism: An NMR Metabolomics Study. Journal of Proteome Research 2017, 16, 1773-1783, 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00035.

- Federica De Castro; Michele Benedetti; Giovanna Antonaci; Laura Del Coco; Sandra Angelica De Pascali; Antonella Muscella; Santo Marsigliante; Francesco Paolo Fanizzi; Response of Cisplatin Resistant Skov-3 Cells to [Pt(O,O′-Acac)(γ-Acac)(DMS)] Treatment Revealed by a Metabolomic 1H-NMR Study. Molecules 2018, 23, 2301, 10.3390/molecules23092301.