An air source heat pump (ASHP) is a system that transfers heat from outside to inside a building, or vice versa. Under the principles of vapor compression refrigeration, an ASHP uses a refrigerant system involving a compressor and a condenser to absorb heat at one place and release it at another. They can be used as a space heater or cooler, and are sometimes called "reverse-cycle air conditioners". In domestic heating use, an ASHP absorbs heat from outside air and releases it inside the building, as hot air, hot water-filled radiators, underfloor heating and/or domestic hot water supply. The same system can often do the reverse in summer, cooling the inside of the house. When correctly specified, an ASHP can offer a full central heating solution and domestic hot water up to 80 °C.

- air source heat pump

- underfloor heating

- domestic heating

1. Description

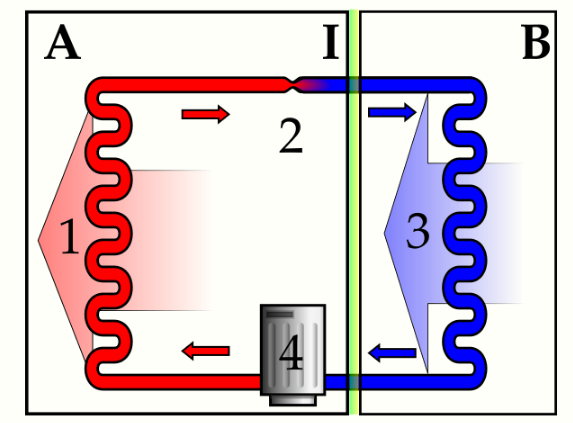

Air at any temperature above absolute zero contains some energy. An air source heat pump transfers some of this energy as heat from one place to another, for example between the outside and inside of a building. This can provide space heating and hot water. A single system can be designed to transfer heat in either direction, to heat or cool the interior of the building in winter and summer respectively. For simplicity, the description below focuses on use for interior heating.

The technology is similar to a refrigerator or freezer or air conditioning unit: the different effect is due to the physical location of the different system components. Just as the pipes on the back of a refrigerator become warm as the interior cools, so an ASHP warms the inside of a building whilst cooling the outside air.

The main components of an air source heat pump are:

- An outdoor heat exchanger coil, which extracts heat from ambient air

- An indoor heat exchanger coil, which transfers the heat into hot air ducts, an indoor heating system such as water-filled radiators or underfloor circuits and a domestic hot water tank.

Air source heat pumps can provide fairly low cost space heating. A high efficiency heat pump can provide up to four times as much heat as an electric resistance heater using the same amount of electricity.[1] The lifetime cost of an air source heat pump will be affected by the price of electricity compared to gas (where available). Burning gas or oil will emit carbon dioxide and also nitrogen dioxide, which can be harmful to health. An air source heat pump issues no carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxide or any other kind of gas. It uses a small amount of electricity to transfer a large amount of heat: the electricity may be from a renewable source, or it may be generated from power stations which burn fossil fuel.

A "standard" domestic air source heat pump can extract useful heat down to about −15 °C (5 °F).[2] At colder outdoor temperatures the heat pump is less efficient; it could be switched off and the premises heated using only supplemental heat (or emergency heat) if the supplemental heating system is large enough. There are specially designed heat pumps that, while giving up some performance in cooling mode, will provide useful heat extraction to even lower outdoor temperatures.

2. In Cold Climates

An air source heat pump designed specifically for very cold climates can extract useful heat from ambient air as cold −30 °C (−22 °F). Manufacturers include Mitsubishi and Fujitsu.[3] One Mitsubishi model provides heat at −35 °C, but the Coefficient of performance (COP) drops to 0.9, indicating that resistance heating would be more efficient at that temperature. At −30 °C, the COP is 1.1, according to the manufacturer's data,[4] although the manufacturer's marketing literature also claims a minimum COP of 1.4 and performance to −30 °C.[5] Although air source heat pumps are less efficient than well-installed ground source heat pumps in cold conditions, air source heat pumps have lower initial costs and may be the most economic or practical choice.[6] A study by Natural Resources Canada found that cold climate air source heat pumps (CC-ASHPs) do work in Canadian winters, based on testing in Ottawa, Ontario in late December 2012 to early January 2013 using a ducted CC-ASHP. (The report does not explicitly state whether backup heat sources should be considered for temperatures below −30 °C. The record low for Ottawa is −36 °C.) The CC-ASHP provided 60% energy (though not energy cost) savings compared to natural gas,[7] when considering only energy efficiency in the home. When considering energy efficiency in electricity generation however, more energy would be used with the CC-ASHP, relative to natural gas heating, in provinces or territories (Alberta, Nova Scotia, and the Northwest Territories) where coal-fired generation was the predominant method of electricity generation. (The energy savings in Saskatchewan were marginal. Other provinces use primarily hydroelectric and/or nuclear generation.) Despite the significant energy savings relative to gas in provinces not relying primarily on coal, the higher cost of electricity relative to natural gas (using 2012 retail prices in Ottawa, Ontario) made natural gas the less expensive energy source. (The report did not calculate the cost of operation in the province of Quebec, which has lower electricity rates, nor did it show the impact of time of use electricity rates.) The study found that in Ottawa a CC-ASHP cost 124% more to operate than the natural gas system. However, in areas where natural gas is not available to homeowners, 59% energy cost savings can be realized relative to heating with fuel oil. The report noted that about 1 million residences in Canada (8%) are still heated with fuel oil. The report shows 54% energy cost savings for CC-ASHPs relative to electric baseboard resistance heating. Based on these savings, the report showed a five-year payback for converting from either fuel oil or electric baseboard resistance heating to a CC-ASHP. (The report did not specify whether that calculation considered the possible need for an electrical service upgrade in the case of converting from fuel oil. Presumably no electrical service upgrade would be needed if converting from electric resistance heat.) The report did note greater fluctuations in room temperature with the heat pump due to its defrost cycles.[8]

3. Longevity

Air source heat pumps can last for over 20 years with low maintenance requirements. There are numerous heat pumps from the 1970s and 1980s in the United States that are still in service in 2012, even in places where winters are extremely cold. Few moving parts reduce maintenance requirements. However, the outdoor heat exchanger and fan must be kept free from leaves and debris. Heat pumps have more moving parts than an equivalent electric resistance heater or fuel burning heater. Ground source heat pumps have fewer moving parts than air source heat pumps as they do not need fans or defrosting mechanisms and are located indoors. The ground array for a ground source installation should last for over 100 years.

4. Usage

Air source heat pumps are used to provide interior space heating and cooling even in colder climates, and can be used efficiently for water heating in milder climates. A major advantage of some ASHPs is that the same system may be used for heating in winter and cooling in summer. Though the cost of installation is generally high, it is less than the cost of a ground source heat pump, because a ground source heat pump requires excavation to install its ground loop. The advantage of a ground source heat pump is that it has access to the thermal storage capacity of the ground which allows it to produce more heat for less electricity in cold conditions.

ASHPs are often paired with auxiliary or emergency heat systems to provide backup heat when outside temperatures are too low for the pump to work efficiently, or in the event the pump malfunctions. Since ASHPs have high capital costs, and efficiency drops as temperature decreases, it is generally not cost-effective to size a system for the coldest possible temperature scenario, even if an ASHP could meet the entire heat requirement at the coldest temperatures expected. Propane, natural gas, oil or pellet fuel furnaces can provide this supplementary heat.

All-electric heat pump systems have an electric furnace or electric resistance heat, or strip heat, which typically consists of rows of electric coils that heat up. A fan blows over the heated coils and circulates warm air throughout the home. This serves as an adequate heating source, but as temperatures go down, electricity costs rise. Electrical service outages pose the same threat as to central forced-air systems and pump-based boilers, but woodstoves and non-electric fireplace inserts can mitigate this risk. Some ASHPs can be coupled to solar panels as primary energy source, with a conventional electric grid as backup source.

Thermal storage solutions incorporating resistance heating can be used in conjunction with ASHPs. Storage may be more cost-effective if time of use electricity rates are available. Heat is stored in high density ceramic bricks contained within a thermally-insulated enclosure.[9] ASHPs may also be paired with passive solar heating. Thermal mass (such as concrete or rocks) heated by passive solar heat can help stabilize indoor temperatures, absorbing heat during the day and releasing heat at night, when outdoor temperatures are colder and heat pump efficiency is lower.

The outdoor section on some units may 'frost up' when there is sufficient moisture in the air and outdoor temperature is between 0 °C and 5 °C (32 °F to 41 °F). This restricts air flow across the outdoor coil. These units employ a defrost cycle where the system switches temporarily to 'cooling' mode to move heat from the home to the outdoor coil to melt the ice. This requires the supplementary heater (resistance electric or gas) to activate. The defrost cycle reduces the efficiency of the heat pump significantly, although the newer (demand) systems are more intelligent and need to defrost less. As temperatures drop below freezing the tendency for frosting of the outdoor section decreases due to reduced humidity in the air.

It is difficult to retrofit conventional heating systems that use radiators/radiant panels, hot water baseboard heaters, or even smaller diameter ducting, with ASHP-sourced heat. The lower heat pump output temperatures would mean radiators would have to be increased in size or a low temperature underfloor heating system be installed instead. Alternatively, a high temperature heat pump can be installed and existing heat emitters can be retained.

5. Technology

Heating and cooling is accomplished by pumping a refrigerant through the heat pump's indoor and outdoor coils. Like in a refrigerator, a compressor, condenser, expansion valve and evaporator are used to change states of the refrigerant between colder liquid and hotter gas states.

When the liquid refrigerant at a low temperature and low pressure passes through the outdoor heat exchanger coils, ambient heat causes the liquid to boil (change to gas or vapor): heat energy from the outside air has been absorbed and stored in the refrigerant as latent heat. The gas is then compressed using an electric pump; the compression increases the temperature of the gas.

Inside the building, the gas passes through a pressure valve into heat exchanger coils. There, the hot refrigerant gas condenses back to a liquid and transfers the stored latent heat to the indoor air, water heating or hot water system. The indoor air or heating water is pumped across the heat exchanger by an electric pump or fan.

The cool liquid refrigerant then re-enter the outdoor heat exchanger coils to begin a new cycle.

Most heat pumps can also operate in a cooling mode where the cold refrigerant is moved through the indoor coils to cool the room air.

6. Efficiency Ratings

The 'Efficiency' of air source heat pumps is measured by the Coefficient of performance (COP). A COP of 3 means the heat pump produces 3 units of heat energy for every 1 unit of electricity it consumes. Within temperature ranges of −3 °C to 10 °C, the COP for many machines is fairly stable at 3–3.5.

In very mild weather, the COP of an air source heat pump can be up to 4. However, on a cold winter day, it takes more work to move the same amount of heat indoors than on a mild day.[10] The heat pump's performance is limited by the Carnot cycle and will approach 1.0 as the outdoor-to-indoor temperature difference increases, which for most air source heat pumps happens as outdoor temperatures approach −18 °C / 0 °F. Heat pump construction that enables carbon dioxide as a refrigerant may have a COP of greater than 2 even down to −20 °C, pushing the break-even figure downward to −30 °C (−22 °F). A ground source heat pump has comparatively less of a change in COP as outdoor temperatures change, because the ground from which they extract heat has a more constant temperature than outdoor air.

The design of a heat pump has a considerable impact on its efficiency. Many air source heat pumps are designed primarily as air conditioning units, mainly for use in summer temperatures. Designing a heat pump specifically for the purpose of heat exchange can attain greater COP and an extended life cycle. The principal changes are in the scale and type of compressor and evaporator.

Seasonally adjusted heating and cooling efficiencies are given by the heating seasonal performance factor (HSPF) and seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER) respectively.

In units charged with HFC refrigerants, the COP is reduced when heat pumps are used to heat domestic water to over 60 °C or to heat conventional central heating systems that use radiators to distribute heat (instead of an underfloor heating array).

7. Risks and Precautions

- Conventional air source heat pumps lose their capacity as the external temperatures fall below 5 degrees Celsius (about 41 degrees Fahrenheit). CC-ASHPs (see above) may operate efficiently in temperatures as low as −30C, although they may not be as efficient in cooling during the summer season as conventional air source heat pumps. If a conventional air source heat pump is used in colder climates, the system needs an auxiliary source of heat to supplement the heat pump in the event of extremely cold temperatures or when it is simply too cold for the heat pump to work at all.

- An Auxiliary Heat/Emergency Heat system, for example a traditional furnace, is also important if the heat pump is malfunctioning or being repaired. In colder climates, split-system heat pumps matched with gas, oil or pellet fuel furnaces will work even in extremely cold temperatures.

8. Controversy

Units charged with HFC refrigerants are often marketed as low energy or a sustainable technology, however if the HFC leaks out from the system, there is potential to contribute to global warming, as measured in global warming potential (GWP) and ozone depletion potential (ODP). Recent government mandates have seen the phase-out of R-22 refrigerant and its replacement with more environmentally sound R-410A refrigerant.[11]

9. Impact on Electric Utilities

While heat pumps with backup systems other than electrical resistance heating are often encouraged by electric utilities, air source heat pumps are a concern for winter-peaking utilities if electrical resistance heating is used as the supplemental or replacement heat source when the temperature drops below the point that the heat pump can meet all of the home's heat requirement. Even if there is a non-electric backup system, the fact that efficiencies of ASHPs decrease with outside temperatures is a concern to electric utilities. The drop in efficiency means their electrical load increases steeply as temperatures drop. A study in Canada's Yukon Territory, where diesel generators are used for peaking capacity, noted that widespread adoption of air source heat pumps could lead to increased diesel consumption if the increased electrical demand due to ASHP use exceeds available hydroelectric capacity.[12] Notwithstanding those concerns, the study did conclude that ASHPs are a cost-effective heating alternative for Yukon residents. As wind farms are increasingly used to supply electricity to the grid, the increased winter load matches well with the increased winter generation from wind turbines, and calmer days result in decreased heating load for most houses even if the air temperature is low.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Physics:Air_source_heat_pumps

References

- "Heat Pumps: The Real Cost". http://www.homebuilding.co.uk/2012/05/09/heat-pumps-the-real-cost/.

- "Air source heat pumps / Choosing a renewable technology". http://www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/Generating-energy/Choosing-a-renewable-technology/Air-source-heat-pumps.

- "Are Air Source Heat Pumps A Threat To Geothermal Heat Pump Suppliers?". Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomkonrad/2014/01/15/are-air-source-heat-pumps-a-threat-to-geothermal-heat-pump-suppliers/. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Mitsubishi ZUBA Cold Climate Air Source Heat Pumps". Encore Heating and Cooling, Kanata, Ontario. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141021195035/http://encore-geothermal.ca/sustainable-solutions/air-source-heat-pumps/. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Zuba-Central". Mitsubishi Electric. p. 5. Archived from the original on 31 July 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140731072149/http://mitsubishielectric.ca/en/hvac/PDF/zuba-central/Zuba-Central_Catalogue.pdf. Retrieved 15 October 2014. "Zuba-Central’s COP ranges from 1.4 to 3.19"

- "Are Air Source Heat Pumps A Threat To Geothermal Heat Pump Suppliers?". Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomkonrad/2014/01/15/are-air-source-heat-pumps-a-threat-to-geothermal-heat-pump-suppliers/. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Cold Climate Air Source Heat Pumps: Results from Testing at the Canadian Centre for Housing Technology". Natural Resources Canada (Government of Canada). Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141020150417/http://www.chba.ca/uploads/TRC/May%202013/Cold%20Climate%20Air%20Source%20Heat%20Pumps%20Presentation%20-%20May%202013.pdf. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Cold Climate Air Source Heat Pumps: Results from Testing at the Canadian Centre for Housing Technology". Natural Resources Canada (Government of Canada). Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141020150417/http://www.chba.ca/uploads/TRC/May%202013/Cold%20Climate%20Air%20Source%20Heat%20Pumps%20Presentation%20-%20May%202013.pdf. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- "Air Source Heat Pump Efficiency Gains from Low Ambient Temperature Operation Using Supplemental Electric Heating: Thermal Storage Supplemental Heating Systems". Minnesota Division of Energy Resources; Minnesota Department of Commerce. 2011. p. 9. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140611123108/http://mn.gov/commerce/energy/images/CIP-AirSource-Pump-Report.pdf. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- Efficiency of heat pumps in changing conditions, http://www.icax.co.uk/Air_Source_Heat_Pumps.html

- US EPA, OAR (2014-11-14). "Phaseout of Ozone-Depleting Substances (ODS)" (in en). https://www.epa.gov/ods-phaseout.

- "An Evaluation of Air Source Heat Pump Technology in Yukon". Government of Yukon’s Energy Solution Centre and Yukon Energy, Mines and Resources. 31 May 2013. http://www.energy.gov.yk.ca/pdf/air_source_heat_pumps_final_may2013_v04.pdf. Retrieved 15 October 2014.